Modern adversaries do not respect the traditional boundaries between space and cyber and neither can the nation.

It starts with silence. The ATM is blank, and you press the buttons harder—nothing. Your phone freezes: Location Unavailable.

On the drive home, traffic lights blink, then die. A news bulletin reports a cyberattack on the power grid, causing rolling blackouts. Moments later, another report states that the U.S. has repelled an adversary’s attempt to seize territory at the cost of its space domain. Gas stations fail, and supermarket shelves run empty.

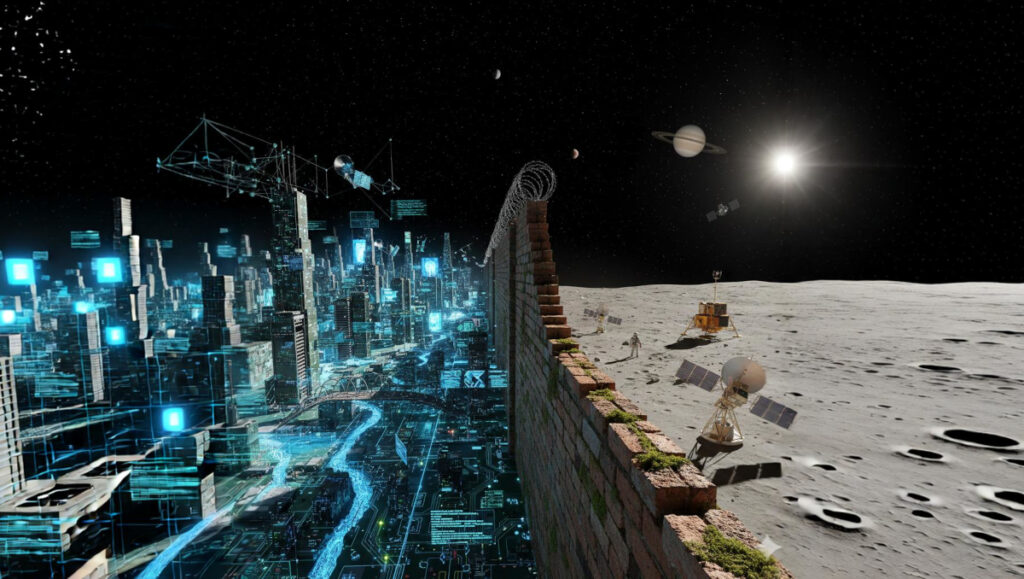

This attack reveals a dangerous truth: modern adversaries disregard traditional boundaries between space and cyber. This disconnect creates a multi-domain blind spot, where capable systems fail to coordinate effectively. Space and cyber influence competitive activities below the threshold of conflict—shaping perceptions and decisions. Without a unified approach, the United States risks losing initiative before conflict begins. Presently, planning treats the domains as distinct, leading to fragmented awareness and exploitable seams for adversaries.

This scenario echoes the cascading effects described in an earlier article, BOOM! LIGHTS OUT, that examined how explosive ordnance disruptions amplify domestic vulnerability. While that analysis focused on the tactical and homeland implications of infrastructure paralysis, this article shifts the lens to a strategic gap: the artificial separation of space and cyber. Modern adversaries exploit these seams long before ordnance detonates, blurring the lines between domains, shaping perceptions, and influencing decision-making below the threshold of conflict.

The Multi-Domain Blind Spot

Modern adversaries do not respect the traditional boundaries between space and cyber and neither can the nation. For decades, these two domains have operated in silos of excellence, shaped by distinct organizational cultures, procedural barriers, and structural divisions in technology, policy, and classification systems. The success of this attack, supporting a land campaign with a multi-domain attack across space and cyber, highlights critical vulnerabilities stemming from the long-standing separation of these areas. While each domain has developed robust capabilities, the lack of integration leaves the U.S. vulnerable to adversaries whose capabilities will likely exceed our abilities to operate seamlessly across domains and exploit our structural gaps. The nation’s systemic preference for specialization over integration has created critical security vulnerabilities, in a battle that acknowledges no borders.

This disconnect creates a multi-domain blind spot in which individually capable systems fail to deliver coordinated effects, their operations existing in isolation. Space and cyber are foundational in competitive activities below the threshold of conflict and large-scale combat. These domains are the backbone of competitive activities that unfold well below the threshold of armed conflict, shaping perceptions, influencing decisions, and preparing the operational environment. In the grey zone, they provide the surveillance, access, and information dominance needed to gain advantage without firing a shot. Those same capabilities become indispensable in large-scale combat, enabling navigation, targeting, communications, and command across every domain. Without integrating them into a unified approach, the United States risks losing initiative before conflict begins.

Despite the domains’ increasing overlap, the nation’s planning and execution frameworks too often treat them as distinct, leading us down the dangerous path of continued fragmented awareness and delayed responses. This separation forces commanders to piece together incomplete pictures and uninformed understanding from different domains, wasting critical decision space when speed and precision are essential. It also creates exploitable seams that adversaries can target with converged operations, striking where our coordination is weakest. Over time, this structural divide slows our decision-making and erodes our ability to anticipate, deter, and outpace threats in an integrated battlespace. Structurally, our defense posture remains disjointed, less than the sum of its parts.

The Interconnected Threat

Modern adversaries—such as Russia, which used GPS jamming during its operations in Ukraine or its complex cyber-attack on Estonia—continue to demonstrate a lack of respect for the artificial boundaries between space and cyber. China continues to pursue cross-domain integration through its concept of integrated joint operations, synchronizing effects across space, cyber, electronic warfare, and conventional forces, which report directly to the Central Military Commission, enabling faster coordination and execution in multi-domain campaigns. Iran and North Korea, while less advanced, have also demonstrated growing sophistication in asymmetric space-cyber operations.

These grey zone, convergent actions reveal a hard truth: our adversaries do not perceive the same artificial lines the U.S. has drawn between space and cyber, and neither can the nation. Attacks increasingly target multiple systems at once, producing cascading effects that compound rapidly. Treating these domains as separate creates blind spots in both detection and response. The opening scenario is illustrative, not because it’s extreme, but because it’s probable. It reflects how tightly integrated our critical infrastructure has become—and how easily our adversaries can exploit that integration.

Furthermore, acknowledging the convergence of space and cyber threats means rethinking how the nation conducts vulnerability assessments. Rather than siloed evaluations, the military needs holistic threat modeling that accounts for system-of-systems dependencies. Building a common operating picture—where data from both domains feed into shared situational awareness—is essential for a timely, effective response. This convergence requires technical interoperability and cultural alignment between historically separate communities. Structuring reforms around organization, technology, and policy reflects how multi-domain failure modes emerge: organizational structures shape how people interpret threats, technologies determine what can be seen and shared, and policies govern whether information and authorities can move across seams. Addressing only a singular, isolated dimension risks preserving the very cultural, procedural, and structural blind spots that adversaries exploit.

Fragmented Awareness

The challenge is not a lack of expertise. The Department of War (DoW) needs deep mastery in every domain. The fundamental problem is that depth has not been matched with integration. Over time, the system has come to reward specialization more reliably than cross-domain fluency. Borrowing the construct of Isaiah Berlin, over time the system has produced an abundance of hedgehogs [experts who know one thing deeply], but far fewer foxes with the breadth to connect ideas across domains. What the military lacks are the integrators: people who can translate, synthesize, and build connective tissue across specialized communities.

The divide between space and cyber illustrates how this dynamic emerged. Each service and intelligence enterprise built capabilities tailored to its mission: Army cyber teams optimized for land operations and expeditionary defense; Navy cyber forces focused on maritime networks and fleet communications; Army space units enabling precision targeting for ground forces; and the Space Force centering on global constellations and strategic space control. These communities developed distinct mental models, operational cultures, and specialized language. What began as necessary specialization has hardened into institutional boundaries that now inhibit collaboration. Classification structures reinforce these divides by limiting visibility, not due to risk but because individuals sit outside the right compartment or billet. Comprehensive, long training pipelines combined with frequent rotations further restrict the development of sustained, cross-domain understanding.

In short, the divide between space and cyber is not rooted in technology but in culture, structure, and process—creating persistent seams that modern adversaries are already positioned to exploit.

These seams have strategic consequences. First, they increase the risk of failure under pressure, as adversaries capable of converging space, cyber, and terrestrial attacks exploit the gaps between our specialized communities, faster than those communities can respond. This first issue has been repeatedly observed in complex cyber-physical disruptions such as power grid attacks. Second, they produce inefficiencies, with capabilities developed redundantly within stovepipes, rather than integrated. Finally, they slow decision-making, forcing planners and commanders to assemble a fragmented operational picture during time-sensitive crises, as seen in incidents where cyber, space, and infrastructure effects unfold simultaneously. In short, the divide between space and cyber is not rooted in technology but in culture, structure, and process—creating persistent seams that modern adversaries are already positioned to exploit.

Toward a More Integrated Approach

Avoiding the strategic surprises that might emanate from the multi-domain blind spot demands reforms in organization, technology, and policy. First, the U.S. must enable secure, real-time data sharing between space and cyber entities. This sharing will require developing interoperable platforms and aligning technical standards to support combined operations. DOW’s Joint All-Domain Command and Control (JADC2) initiative aims to enable seamless decision-making across all domains, including space and cyber. While promising in concept, its success depends on more than just technology—it requires breaking through classification barriers, aligning service cultures, and ensuring interoperability across disparate networks and sensors. Without cultural and structural reform, JADC2 risks becoming another technically sophisticated tool constrained by legacy divisions.

Second, classification policies must be revisited. Overclassification remains one of the most persistent barriers to integration. A risk-based approach—focused on protecting true national secrets while enabling necessary collaboration—can unlock significant value. Policy directives currently aim at the production points, which demand relevant tear lines to release information from sub-compartments to strengthen planning and integration. Failure to move in this direction leaves commanders with a fragmented understanding of the operational environment and an inability to truly mitigate risk. Removal from compartmented programs and using lower classification where feasible can promote broader operational awareness.

Historically, personnel have been trained to focus on the tools at their disposal rather than the outcomes they need to achieve. In kinetic operations, ground forces request effects—such as “suppress enemy air defenses”—rather than specific munitions. That same model should now apply across space and cyber, empowering users at every level to request outcomes like disrupting enemy command and control or denying satellite communications, without needing detailed knowledge of the assets required. Embedding this mindset into training, doctrine, and planning cycles will foster adaptability, narrow the gap between users and specialists, and keep planners focused on objectives while domain experts determine how best to achieve them. Combined with cross-domain training and shared situational awareness, it creates the unified operational environment needed to counter adversaries who exploit seams between space and cyber.

Joint training is equally critical. Historically, space and cyber operators have trained and exercised in isolation. This structure must change. Cross-domain exercises simulating converged attacks will help expose vulnerabilities and refine response protocols. These exercises must be realistic, iterative, frequent, and involve integrated teams of space and cyber experts working side by side. Beyond technical readiness, such collaboration builds mutual trust and familiarity, softening institutional boundaries.

Finally, while this last solution will not be cheap or a quick fix, the U.S. government must invest in building a workforce designed for convergence. That means cultivating “T-shaped” professionals with deep expertise in one domain and a broad understanding of others. Educational curricula, certification programs, and professional development pathways must reflect this need. Incentives should reward personnel who pursue cross-domain training or joint assignments. Career progression models must value integrative thinking as much as domain mastery. This development supports the Secretary of Defense’s memo to allow military members to “specialize in lieu of gaining generalized experience across a range of functions.”

Conclusion

The future of conflict is already here, and it does not respect the lines drawn between space and cyber. Our adversaries operate fluidly across domains, integrating actions to expose strategic flanks, leaving the U.S. susceptible to surprise and unrecognizable effects. If the nation clings to outdated separations, it invites disruption. The multi-domain blind spot is not an abstract flaw but a structural weakness that can be exploited at speed and scale.

But it’s also solvable. The capabilities already exist. Integration is missing—shared awareness, interoperable systems, and a unified operational mindset. The U.S. can turn fragmentation into fusion by building secure information pipelines, adjusting classification protocols, expanding joint training, and cultivating cross-domain expertise. Most importantly, by training our personnel to request effects rather than assets, the military shifts the focus to outcomes, where they belong.

This fundamental change is not bureaucratic refinement but a strategic imperative. Converged threats demand a converged response. The U.S. can maintain its strategic edge in an increasingly contested battlespace by seeing the whole picture—understanding how space and cyber intersect and preparing to act accordingly. The U.S. needs to break down bureaucratic divisions and build a unified culture that understands the interconnectedness of space and cyber warfare. Our adversaries already fight without boundaries; if the U.S. cannot do the same, our strategic edge will evaporate in real time.

Catherine R. Cline is a U.S. Army major and strategist with operational experience in space, cyber, and special operations and holds a master’s degree in cybersecurity. She currently serves in a joint assignment at U.S. Space Command.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Credit: Created by Gemini