“I hate GPS. The idea that we are all hooked to a satellite…that doesn’t work in certain circumstances, does not work indoors or in valleys in Afghanistan, is ridiculous.”

– Former Secretary of Defense Honorable Ashton Carter, June 2014

The Department of Defense (DoD) needs to focus its efforts on modernizing the way it delivers position, navigation, and timing (PNT). Without a fundamental shift away from the Global Positioning System (GPS), the DoD will not be competitive in near-peer conflicts.

The 1990s’ GPS technology revolution gave the DoD access to extremely accurate PNT data. It also gave the U.S. military an unparalleled advantage. As GPS became more reliable and accessible, the United States and many countries used its data for everything from recreational activities to transportation, banking, and agriculture. While the system started as a military capability, the civilian market now relies on it for computer networks, commercial aviation, and railroads. Power grids, of all things, make up the vast preponderance of GPS receivers.

America’s adversaries took note of this capability and soon developed similar global navigation satellite systems (GNSS). They also invested heavily in capabilities to deny the U.S. military its GPS access. In any future conflict with a near-peer adversary, the U.S. military can therefore expect to operate in a GPS-denied environment. This means the DoD needs to develop a comprehensive strategy now, to both manage a transition away from GPS and to pursue more resilient forms of PNT.

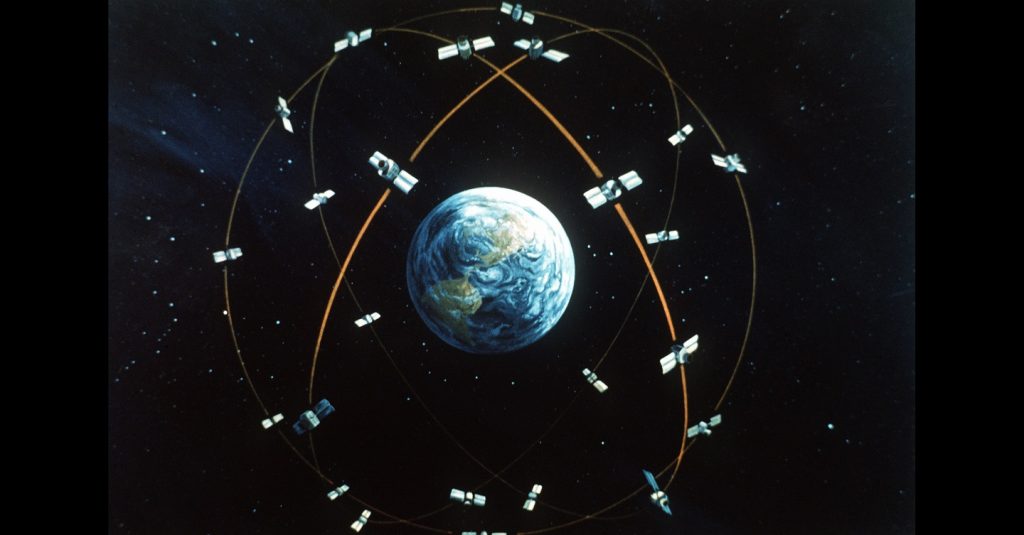

Since 1973, when the U.S. Air Force (USAF) opened its GPS Program Office, USAF’s GPS satellite constellation has grown to 30 operational satellites today – not counting the decommissioned satellites or on-orbit spares – orbiting in space at altitudes of approximately 12,550 miles.

Military and civilian receivers need to be in view of at least four GPS satellites to receive the relatively weak signals they broadcast, to obtain an accurate location. By the time a GPS target ‘hears’ its satellites’ signals, it’s comparable to trying to see a 40-watt household light bulb from over 12,550 miles away. Once these GPS signals reach the planet, they can’t penetrate structures or sub-surfaces. Only when a receiver antenna has clear line-of-sight to the sky can it grab its PNT signal. The satellite signals’ low power means that GPS receivers must depend on external antennas, mounted atop buildings or vehicles, to lock onto signals from space. This line-of-sight restriction also impedes operations in mountainous terrain, such as in Afghan valleys or in dense, urban mega-cities, where the Army expects to fight in the future. The military could live with these types of limitations in the 1970s; today, they pose an unacceptable risk. So does bandwidth encroachment.

The electromagnetic spectrum’s (EMS) bandwidth is finite and open for all to use. Any electronic device that uses a radio frequency does so through a portion of the EMS, and the U.S. government restricts use of EMS sections which surround those reserved for GPS signals. Another example of government restriction of the EMS occurred after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the U.S. homeland. Congress authorized the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to dedicate 20 megahertz of the EMS for a public safety network. This government-led encroachment of spectrum bandwidth seizes sections from existing wireless communications users, which further restricts EMS space for the commercial market’s use. The need for bandwidth will only get more contentious as new systems and networks come online in the future.

GPS satellites broadcast five signals in the L band. The letter “L” refers to the Institute for Electrical and Electronic Engineers’ (IEEE) designated band of the electromagnetic spectrum (EMS) in which GPS signals transmit. Ligado Networks LLC (“Ligado”) is a U.S.-based company which is developing 5G technology for over-the-air internet, from low-Earth orbit satellites that are planned to also broadcast in the L Band. The FCC approved Ligado’s application to deploy a terrestrial network in three frequency bands that will primarily support that company’s Internet of Things (IoT). However, the DoD determined Ligado’s network will “cause unacceptable operational impacts and adversely affect the military potential of GPS.” As the challenge of such signal encroachment worsens, the DoD must mitigate its risk by moving away from GPS as its PNT source.

Though GPS enables U.S. DoD capabilities, three other GNSS constellations vie for space, as well as two regional ones that provide others’ their PNT data. The European Union, the Russian Federation, and the People’s Republic of China are all developing and operating GNSS constellations. The governments of India and Japan also have constellations that cover their respective regions. Of these systems, only the Japanese one – Quazi-Zenith – complements GPS; the others compete with it.

If this weren’t enough, Russia, China, and other adversaries manufacture and proliferate GPS jammers to deny the U.S. military access to its GPS. Jammers transmit signals at higher power than GPS satellites, which prevents GPS signals from reaching a receiver. Russia and China view electromagnetic warfare as an integral aspect of modern conflict and have dedicated units that are manned, trained, and equipped just to attack GPS signals. Chinese electromagnetic warfare units routinely jam GPS signals, in force-on-force exercises. Jammers aren’t the only threat.

Russia leads in the development and fielding of GPS ‘spoofers.’ Spoofing is more complex than jamming: the spoofer broadcasts a signal that tricks a GPS receiver into thinking the spoofer is a valid emitter, thereby hijacking the receiver. Russia spoofed the GPS signal 10,000 times in just two years. It’s time to respond.

The DoD should take the lead on developing a comprehensive PNT strategy which capitalizes on the February 2020 “Executive Order on Strengthening National Resilience through Responsible Use of Positioning, Navigation, and Timing Services.” This executive order directs the Office of Science and Technology Policy to develop a national plan to develop secure PNT services that don’t depend on GPS. A DoD PNT strategy will focus the Department’s efforts on developing a set of solutions that endure in future contested environments. The DoD and other agencies are already working on several different PNT capabilities, but few are collaborating. This opens an opportunity for the DoD to take the lead and to shape the future of national PNT capabilities.

Its use is so ingrained in everyday life that it’ll take time before the United States can be weaned off the ‘digital addiction’ GPS enables.

The DoD should establish a PNT Modernization Priority element within the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Research and Engineering (OUSD [R&E]). Under this office, the DoD could create a comprehensive PNT strategy that could focus the Department’s efforts on developing capabilities that achieve the Executive Order’s mandate and that also meet the Services’ needs.

Beyond that, the DoD should ask Congress to stop funding GPS. Its use is so ingrained in everyday life that it’ll take time before the United States can be weaned off the ‘digital addiction’ GPS enables. The existing satellites and ground infrastructure should continue to work well into the future in a benign environment — long enough for the DoD to field PNT replacement capabilities. Rather than investing an additional $5.8B to build the 10 GPS Block III satellites and $6.2B in upgrading their control segment, the DoD should continue to only operate the existing GPS constellation and should invest those funds into new PNT technologies.

Finally, while the DoD continues to use GPS for now, there are other technologies that can reduce and eventually eliminate U.S. reliance on it. The DoD needs to redirect its funds toward them. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has multiple efforts under development to replace GPS. Many are for discrete positioning, navigating, or timing components. Today, we think of the three capabilities together, as one capability, but the challenge of assured access doesn’t mean they have to be.

For example, the Common Timing Protocol is one of the critical services that GPS provides. GPS time transfer is made possible, in part, because there are atomic clocks within each GPS satellite. GPS time transfer is the method for synchronizing clocks and networks to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). These are accurate to within 40 nanoseconds (40 billionths of a second. DARPA projects – such as Chip-Scale Atomic Clocks (CSAC) are already available on the commercial market. A major benefit of CSAC technology is in its small size and portability. The atomic clocks that GPS relies on are large, expensive devices. Embedding CSACs into military and commercial receivers will eliminate the need for access to an easily denied signal. Integrating CSACs into military equipment will enable the DoD to transition away from GPS toward a more resilient form of time transfer.

Quantum Information Science (QIS) is another area that will provide PNT capabilities which could replace GPS. DARPA is developing quantum-based PNT capabilities such as Quantum-Assisted Sensing and Readout (QuASAR). QuASAR is intended to build measurement tools based on atomic properties, which can replace existing navigation systems’ ways of figuring out where they are. In other words, these atomic properties aren’t vulnerable to “drifting” over time; they self-calibrate. This makes them ideal for precision sensing. While QIS is still in its infancy, existing developments show its significant promise with a broad array of applications, to include PNT. Other precision technologies may help the DoD take the fight underground, literally.

Subterranean warfare has been a part of military operations in challenging battlefields throughout history; however, GPS-enabled navigation has never been an option underground. Starting in 2017, DARPA’s Subterranean Challenge has been seeking new approaches to navigate underground areas. This challenge has three preliminary “circuit events” that have already occurred, and a final integrated challenge course is planned for fall, 2021. Out of this challenge, DARPA hopes to develop systems to rapidly navigate unknown, complex, subterranean environments. Such advancements would yield the U.S. military PNT data in places where GPS can’t penetrate.

GPS has served the DoD and the world for more than 40 years. However, if the DoD wants to remain militarily competitive in 2040, GPS is not the answer. The DoD needs to develop a comprehensive PNT strategy under OUSD (R&E) leadership, that cuts across several of the existing modernization priorities, with a focus on emerging PNT capabilities. Rather than investing billions of dollars each year to upgrade a vulnerable legacy capability, the DoD needs to develop and field other forms of PNT services that are more resilient and can operate in a contested environment without letting adversaries – like China – achieve these capabilities first. Some argue that China is already leading the world in QIS technology as it was first to achieve three significant QIS milestones between 2016 and 2018 (a quantum satellite launch, a quantum long-distance landline, and a quantum long-distance videoconference).

The DoD should focus its efforts on revolutionizing PNT delivery. Without this fundamental shift in thinking about how to solve these challenges, the DoD will not be competitive in near-peer conflicts. American service members may even find themselves lost on their next battlefield.

Robert Hoffman is a U.S. Army Reserve officer currently commanding the I-Corps MCP-Od and a Department of the Army Civilian as the Chief, Space Operations Training Division. He is a graduate of the AY21 Resident Class at the U.S. Army War College.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Artist’s global concept of the NAVSTAR Global Positioning System Satellite circa 1981

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the The U.S. National Archives