Today, the use of coercive military force is limited by increasing international economic interdependence and global nuclear deterrence strategies.

Introduction

As the joint force refocuses U.S. national security strategy to address great power competition, it must update its institutional development approach to incorporate frameworks representative of new security architectures. The majority of military theories that underpin modern U.S. strategy and doctrine are drawn from Napoleonic Era theorists who focused heavily on decisive battlefield conflict. In today’s post-information age, however, armed conflict represents the least likely manifestation of competition. Today, the use of coercive military force is limited by increasing international economic interdependence and global nuclear deterrence strategies. Consequently, the current strategic operating environment demands a deeper understanding of limited warfare tactics, competitive activities below levels of conflict, and information dominance to achieve strategic objectives. Sun Tzu’s seminal work, “The Art of War,” provides context that can help the United States better understand how to win without fighting, how to overcome a proclivity to utilize coercive force, and how to cultivate nonbinary understandings of war, peace, and competition.

While the theories of Carl von Clausewitz, Antoine-Henri Jomini, Napoleon Bonaparte, and other eighteenth and nineteenth century European military strategists are still applicable in planning and conducting large scale ground combat operations, they are inadequate to wholly inform strategies for conflict below the threshold of war. The use of proxy forces, political subversion, economic coercion, information operations, and lawfare, represent the most likely rival courses of action in a global security environment that restricts the utilization of coercive force. Extensive levels of economic interdependence and the proliferation of nuclear weapons have created a systemic restriction on waging total or unrestricted warfare, and thus have limited the usefulness of coercive military force.

Sun Tzu wrote and fought during the Warring States Period of Chinese history in which “Seven major states vied for control of China… Sandwiched between these were several smaller states but the big seven had by now become so large and consolidated that it became difficult for one to absorb another.” Though nearly 2400 years ago, there are two primary systemic parallels between the Warring States period and the security environment that the United States faces today: 1) a structure in which great powers overtly compete for influence relative to one other and over minor states through which they often operate, and 2) technological advances that make war more lethal and costlier.

Many of the United States’ adversaries have already developed operational strategies to avoid decisive military engagements. If the United States fails to expand its binary approach to security, it will experience competitive disadvantages in the era of great power competition.

In “The Art of War,” Sun Tzu examines alternatives to mass, protracted warfare and proposes strategies based on deception, surprise, alliance balancing, and information dominance that better align with the realities of global competition today. Given the contextual parallels between the Warring States Period and the current era of great power competition and Sun Tzu’s insight into irregular warfare strategies, studying “The Art of War” will help the United States develop the strategies necessary to adapt to and compete in the modern security environment.

The Operational Environment

In 2017, the United States pivoted away from the counter terrorism and nation building policies that defined U.S. international engagement during the global war on terror (2001-2017) and towards state-centric competition. This shift is codified in the 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS) which states, “After being dismissed as a phenomenon of an earlier century, great power competition returned.”

The massive modernization efforts undertaken by the Department of Defense (DOD) were also a pivotal part of this shift in strategy. These efforts, such as the Army’s $187.5 billion “Big Six” and the $400 billion nuclear force/arsenal modernization, focused on improving platform-based technology. The DOD’s initiatives will increase the United States’ comparative military advantages over rival states in direct military conflict. Consequently, they will reinforce systemic deterrents to armed conflict and encourage rivals to compete at levels below armed conflict. If the United States fails to more effectively balance conventional and unconventional military capabilities, it risks developing vulnerabilities in the space between war and peace.

The Irregular Warfare Annex to the National Defense Strategy articulates this point: “As [the U.S.] seeks to rebuild our own lethality in traditional warfare, our adversaries will become more likely to emphasize irregular approaches in their competitive strategies to negate our advantages and exploit our disadvantages.”

Sun Tzu’s prescription reveals why the United States is struggling in competition with revisionist actors below levels of armed conflict.

Strategic Priorities

Russia and China, the two principal revisionist actors codified in the 2017 NSS, have both developed an array of unconventional strategies that focus on expanding their international influence to achieve national security objectives. Russia’s Gerasimov Doctrine and China’s Three Warfares strategy both seek to expand global power and influence through the synchronization and execution of below established threshold activities. The strategies utilize multiple elements of national power not only to pursue national interests but also to subvert U.S. foreign policy goals without inciting armed conflict.

Furthermore, to strengthen their competitive positions, Russia and China are taking advantage of the systemic restrictions inherent in great power competition. China has deployed anti-access area denial platforms and coercive economic practices in order to obstruct U.S. objectives and destabilize U.S. alliance structures. Similarly, Russia has made efforts to degrade the NATO alliance via information operations and destabilized Eastern Ukraine through the annexation of Crimea and deception, information operations, and utilization of proxies.

Sun Tzu writes that the ultimate goal of warfare is to win without fighting: “Hence to fight and concur in all your battles is not supreme excellence, supreme excellence consists in breaking the enemy resistance without fighting.” Sun Tzu presents a hierarchy of actions to achieve this goal: “the best approach in war is to first attack the enemy’s strategy. The next best approach is to attack the enemy’s alliances. The next best approach to that is to attack his army. The worst thing to do is to attack his cities.” Sun Tzu’s prescription reveals why the United States is struggling in competition with revisionist actors below levels of armed conflict. The United States centers its entire security strategy around armed conflict and views the world through a binary construct of war and peace. The United States is either targeting enemy forces or not. In order to more effectively compete with actors like China and Russia, the United States ought to apply Sun Tzu’s recommendations and consider his definition of excellence in warfare: “breaking the enemy’s resistance without fighting,”

Information and Deception

To remain a global competitor, the United States must also prioritize military strategy in power domains of increasing importance, most notably, the information warfare domain. While often ignored or delegitimized in the writings of Napoleonic era theorists, generating advantages in the information domain is a vital element to achieving success in the modern operating environment. In “On War,” Carl von Clausewitz questions the importance of deception and simply accepts the concept of the “fog of war”as an inevitable reality: “But however much we feel a desire to see the actors in War outdo each other in hidden activity, readiness, and stratagem, still we must admit that these qualities show themselves but little in history, and have rarely been able to work their way to the surface from amongst the mass of relations and circumstances.” Conversely, Sun Tzu emphasizes the critical role that information and information-related-deception plays in achieving the ultimate goal of winning without fighting. In “The Art of War,” Sun Tzu writes, “All warfare is based on deception.” Furthermore, Sun Tzu emphasizes the importance of deception through the exploitation of known enemy agents by “doing certain things openly for purposes of deception and allowing our spies to know of them and report them to the enemy.”

Conclusion

Within the era of great power competition, U.S. policymakers must develop alternative concepts of limited warfare and competition executed below established thresholds. As the joint force adopts the competition continuum which describes an operating environment of enduring competition carried out by a mixture of cooperation, competition below armed conflict, and armed conflict, it would do well to heed Sun Tzu’s advice. Sun Tzu’s “Art of War” provides important theories that can help policymakers and military professionals develop alternatives to armed conflict. The joint force should not altogether abandon Carl von Clausewitz and other Napoleonic era theorists. Rather, Sun Tzu’s “The Art of War” ought to complement the foundational theorists and bolster the theoretical underpinnings of U.S. national security across all elements of the competition continuum. Many U.S. rivals understand the limitations inherent in the modern operating environment and are using the limitations to their advantage to challenge and erode U.S. influence. If the joint force continues to focus exclusively on armed conflict, it will find itself at a precarious disadvantage as revisionist states incrementally degrade U.S. advantages, influences, and alliances without physical fighting. “The Art of War” is not a magic bullet for success in the era of great power competition, but it provides important ideas and a foundational framework to help the United States better understand both the modern operating environment and rival states’ unconventional strategies. The text can help the joint force to begin constructing more comprehensive, expansive, and relevant U.S. security strategies to succeed in the new era of great power competition.

MAJ James P. Micciche is an Army Strategist and the G5 at the Security Forces Assistance Command (SFAC). He holds degrees from the Fletcher School at Tufts University and Troy University. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

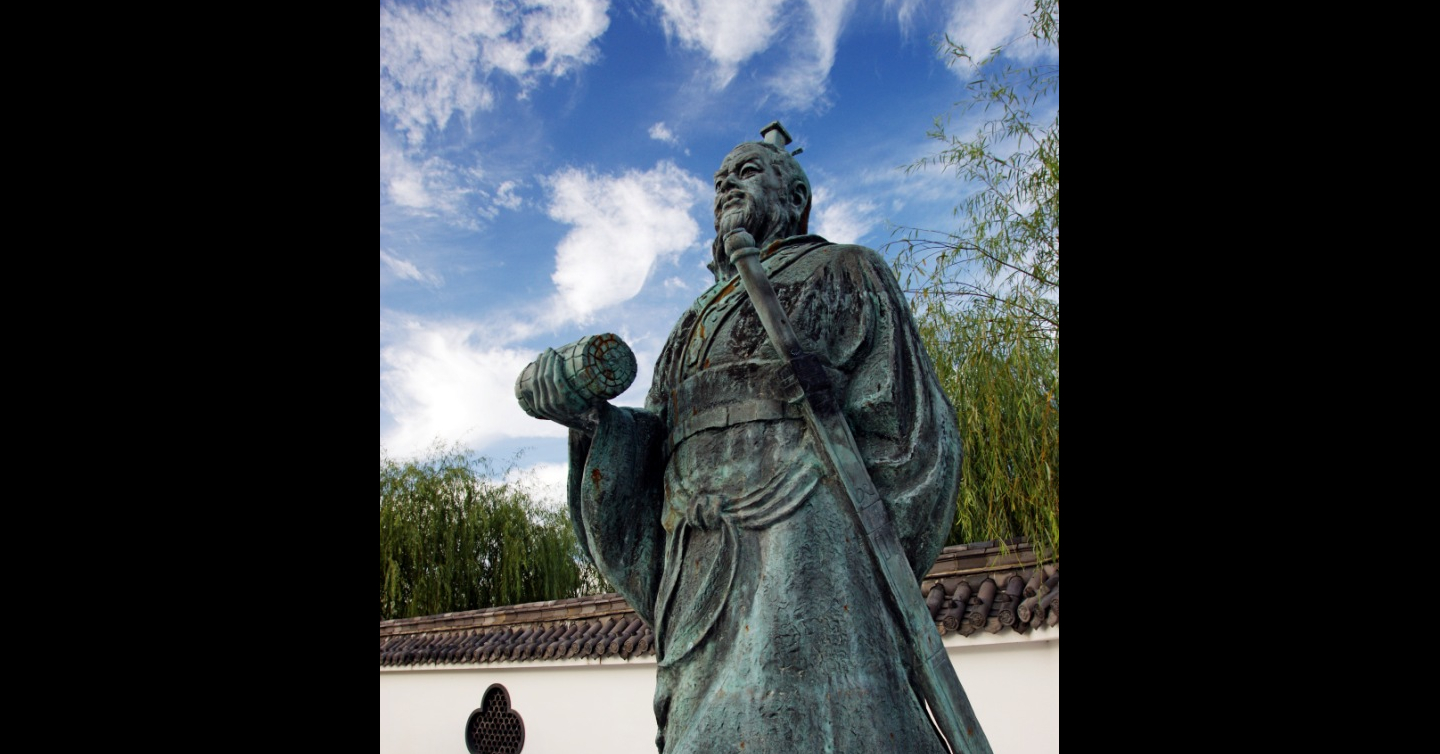

Photo Description: Statue of Sun Tzu in Yurihama, Tottori, in Japan

Photo Credit: 663highland via Wikimedia Commons