No amount of strategy, operational art, or tactics can overcome a lack of national will

In the United States, the employment of military forces is controlled by the military’s civilian, political masters. Subordination of our military to the civilian power is in line with our finest political traditions. It is a keystone of our democratic system.

But this principle seems to have no consequences when it comes to discussions of accountability. Donald Rumsfeld infamously observed that “[y]ou go to war with the Army you have – not the Army you might wish you have.” But who is responsible for the army we have? Civilians decide how and when America goes to war. Civilians are responsible for defining the four corners within which the military fights. Absent a deficient military strategy or poor execution, perhaps the civilians might legitimately shoulder much of the blame when things do not go well?

When I worked as an attorney, I learned that no amount of heroic lawyering can make up for early-stage, fundamental business decisions made by the client. For example, if competitive pressures demand that a client not require payment from customers in advance, then later that client will inevitably pursue more claims arising from customers’ failure to pay. The downstream risk is inherent in the way the client decided to do business.

So it is with nations and wars. In endlessly wondering how we lost Vietnam (or, say, in the discussions that we will have about Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria), Army leadership often deludes itself that bad results could have been overcome by better doctrine, or by the application of more effort and expert military know-how. The Army can certainly improve how it operates and learn from its past, but no amount of strategy, operational art, or tactics can overcome a lack of national will. Once Nixon made the decision to get out and Congress cut off U.S. aid to our southern ally, the gig in Vietnam was up. Surely America lost that war, but did the Army?

Military professionals often bemoan a lack of national strategic focus for US military action. Despite the excellent work that goes into the National Military Strategy and the National Defense Strategy, these are necessarily descriptive of the mission that civilian leaders have set; they do not dictate national strategy. In actuality, combatant commands build their mission sets based on how each can best obtain, maintain, and position its own capabilities in the current fiscal environment.

The Army can position itself to fight and to win, but it needs the political backing, strategic guidance, and national will (money) to do so. When those items are not forthcoming, it should be a foregone conclusion that the military aspect of things will not go well. Duh.

At the institutional level, the Army performs every commander’s trick of taking his or her superiors’ decisions and adopting them as his or her own. While this is all well and good for unity of command and motivating soldiers, at some point Army leaders must acknowledge that a Presidential decision to reduce forces or a Congressional decision to reduce funding is not conducive to winning a war. Those who have invested their own time, sweat, and blood into making an American intervention successful may disagree with such a decision, but it is what it is. Don’t take it personally. America simply does not have a lot of staying power when it comes to international conflict. Everyone else already knows this.

There is also a tactical disingenuousness when it comes to American withdrawals. When America abandons our allies, the Army goes to great pains to deny that fact. This denial becomes an imperative talking point for forward deployed personnel: we aren’t pulling back, we are just using “dynamic force employment” to back you up in a new and innovative way, dear friends. Yeah, that’s what we are doing.

While it makes sense to put a brave face on U.S. withdrawals to reassure our allies and contain our enemies, American military personnel eventually believe their own shtick. Unlike people raised under more cynical regimes, Americans are straightforward. If one’s superiors say American forces are not withdrawing from any given region, and one continually repeats to one’s allies that America is not withdrawing, sooner or later one comes to believe that America is not withdrawing. As a result, even as military personnel execute an alarmingly predictable withdrawal (and our recent history is replete with them), American personnel don’t accept that America is pulling out. If America says we are simply executing our alliance in a different way, gosh darn it, then that’s what we are doing. This failure to perceive the obvious interferes with planning, asset allocation, and a host of other decisions at the tactical level. There is no profit in lying to ourselves.

Our military’s inability to admit “it’s over” is more than just an American unwillingness to admit anything that looks like defeat, it is exacerbated by the perceived need within each combatant command to maximize the importance of its own geographic area, so as to more effectively compete for DOD resources. As a result, no staff officer below Chief of Staff level can admit that U.S. involvement in region X is now a low priority and the military is shifting assets, forces, and strategic focus elsewhere, because “elsewhere” belongs to a different four-star general. Military personnel feel compelled to repeat to each other what their bosses are sending up the chain as though it were true. Even when it isn’t.

In believing what we say to cover our exits, Americans in uniform ignore the lessons learned by the Kurds, Hmong, South Vietnamese, and Sunni tribesmen in Iraq. Even worse, service personnel often ignore the ground truth they themselves are experiencing. When it all falls apart, looking back and trying to square their own, lived experiences with the party line leads to preposterous attempts to retroactively over-think things, trying to convince themselves that two and two should have made five, that there really were five lights, and that we should have been able to do it all with fewer forces.

Many of the worst abominations in Army doctrine result from twisting observed facts to conform to shared, preconceived notions, like early astronomers struggling to make the facts of elliptical orbits fit into their “mystical belief that the circle was the Universe’s perfect shape,” to use the words of one NASA writer. Instead of accepting that American policy sometimes changes radically, the Army lets out a collective sigh. Aw, shucks, if only we had been smarter at thinking this stuff through. Perhaps long-range American military planning should simply start with the assumption that national will in support of any given intervention will start to wane by the third year, will be almost completely absent by the fifth year, and is unlikely to survive in any recognizable form beyond the end of the Presidential administration that initiated it?

Many of the worst abominations in Army doctrine result from twisting observed facts to conform to shared, preconceived notions

The Army has a non-negotiable contract to fight and win the nation’s wars, but the wars in questions are the nation’s. To fight. To not fight. To resource. To abandon. As soldiers, we just work here. Military leaders can put on a brave face and “own” the decision out of solidarity with our nation’s leaders, to soothe our allies, and to threaten our adversaries, but speaking amongst themselves they would be well served to dispense with the doublespeak. A battalion is not a brigade. And a brigade isn’t three divisions. Less is less. And no, the American people aren’t going to use strategic nuclear weapons to protect some small ally in a far-flung corner of the world where we can’t even be bothered to permanently station troops. Being a military professional should not entail blind obedience to national talking points. Fighting and winning our nation’s wars should not include acting as a shill for ever-shifting national policy priorities or an apologist for our nation’s short attention span.

Perhaps the clearest example of how today’s “strategic vision” merely reflects everyday politics are U.S. plans for total mobilization. As active forces shrink, presenting a credible threat to adversaries must involve a plan to mobilize a several million-strong wartime army in a reasonable period of time. Without this, America cannot be expected to be taken seriously as potential ally or adversary. The Navy/Marine Corps team can do a great deal to project power in between wars. The Air Force has always sold strategic air and missile forces as capable of doing any job, but we have always known that not to be true (at least not on any version of the Earth that we would still want to inhabit). America may not have—or be able to afford—a standing Army of great size, but we need to be able to raise one if needed.

As such, the selective service process needs to work and needs to be seen to work. Currently, it does not. Requisition levels (the Selective Service Administration’s potential mission, as set by the DOD) have not been re-evaluated in some time (2018 GAO Report: “DOD provided the personnel requirements and timeline that were developed in 1994…officials stated that they did not conduct additional analysis to update these requirements because the all-volunteer force is of adequate size and composition to meet DOD’s personnel needs.”), are unrealistically low and slow (“[T]he first 100,000 inductees would report for service in 210 days…”, ibid.), there is little emphasis on testing the system, and no one cares about it. SSA is severely under-resourced (SSA is only authorized 124 full-time employees and hasn’t had a budget increase in 30 years; if activated, the system would rely on volunteers and retiree recalls). SSA’s decrepitude is an entirely appropriate political result, as the draft is political Kryptonite. It is also very, very poor strategy.

Intermediate systems are similarly ignored. I have written elsewhere on the lack of institutional enthusiasm for the Individual Ready Reserve—not because the IRR makes no strategic sense, but because of a profound lack of political will. Similarly, the use of the reserve component provides one way to mitigate the risk of a small standing Army, but the use of National Guard combat formations to backstop cuts to active force structure has also been limited by internecine rivalry (the active Army conspires to keep the reserve component as a set fraction of the active army’s size, preventing affordable reserve component force structure from growing to replace costly active component force structure).

As these examples demonstrate, and as is clear to anyone who has spent time in the Pentagon, “strategic” causes are championed based on what can be funded. An institutional desire to engage in long-term strategic thought–and fund what is necessary to effect that strategy–is almost wholly secondary, if not absent. The American people are simply not willing to think that far ahead. They change their minds often and in very predictable ways. The military must do its best to live with that.

Military professionals spend a lot of time being educated and forming views on how best to prepare for and wage war. But when it comes time to implement a strategy, military men and women simply pretend that the right answer is the current, institutionally-championed answer. What it really turns out to be is something much simpler: an answer based on politics–the art of the possible–and the role that the Army has negotiated for itself in the midst of the inevitable inter-service rivalry for missions and dollars.

Perhaps the best path for the Army is to remain flexible, with near term options (draft, leveraging private industry, etc.) available to change strategic directions as the situation warrants. Necessary capacities (like Army surface vessels) will suffer if we lack the ability to allocate long-term dollars against them. That may be no way to run a circus, but it’s the only show in town. We just work here.

Garri Benjamin Hendell is a major in the Pennsylvania Army National Guard. He has three completed overseas deployments to the CENTCOM area of operations, three overseas training missions to Europe, leadership and staff positions at the platoon, company, battalion, brigade, division, and joint force headquarters level, as well as having served both in uniform and as a civilian branch chief at the National Guard Bureau. Among other things, he is a graduate of the Army’s Red Team course.

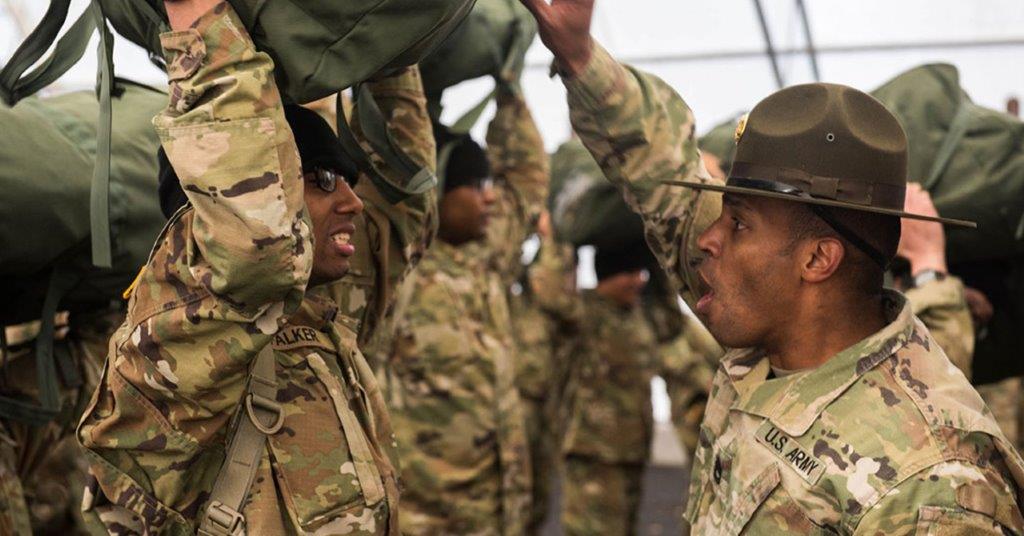

Photo: Drill sergeants welcome new Soldiers at Fort Leonard Wood for Initial Entry Training, 2019.

Photo Credit: U.S. Army photo, public domain.