In my view, the recent misguided attention paid to materials used for developing our military officers at all levels of professional military education is detrimental.

In June 2023, I was honored to attend the National Security Seminar held at the U.S. Army War College. This year’s theme for the National Security Seminar was an examination of civil-military relations. I found the week extremely rewarding, and I was amazed at the different issues that emerged related to civil-military relations in the nation. One of the issues raised was the issue of “wokeness” in the military, which has been a touchstone of the current political debates. In August 2023, news outlets ran stories about how the Chief of Naval Operations removed several books from his recommended reading list that were controversial and dealt with race issues.

This is both unfortunate and upsetting. In my view, the recent misguided attention paid to materials used for developing our military officers at all levels of professional military education is detrimental. It is stunting individual readiness and the overall ability of the military to defend our nation.

As a historian, let me present a case study over past discussions about teaching politically charged subjects and how it pertains to the U.S. military. While researching a different topic, I stumbled upon a debate that occurred at the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1934-1935 over whether cadets in a mandatory economics class should be taught about the New Deal. It was as contentious and polarizing as the modern discourse on “wokeness.” I believe this historical event can provide valuable guidance for current discussions on books and current professional military education.

Since 1802, West Point has been producing Army officers and leaders for the nation. From presidents to generals to writers to business leaders, West Point has been one of the leading institutions of higher education in the nation. However, by the end of World War I, West Point had entered a period of ennui and was more worried about the trappings of education and parade ground military and not producing military leaders that could meet the complex geo-political world the United States faced in the early 20th century. Under the leadership of General Douglas MacArthur, the superintendent after World War I, West Point began teaching more social sciences and history as a crucial part of the curriculum. MacArthur ordered the establishment of a Department of Economics, Government, and History. In 1930, the department was chaired by Lieutenant Colonel Herman Beukema (USMA Class of 1915), a distinguished artillery officer during the Mexican War and World War I. Beukema returned to West Point in 1928 to teach social studies and eventually became the head of the department in 1930. Beukema would later go on to become one of the nation’s early experts on geopolitical thought, as well as a teacher and mentor to Brigadier General George A. Lincoln and other prominent Cold War-era strategic thinkers, including General Andrew Goodpaster (the namesake for the Army’s Goodpaster fellows, a cohort pursuing doctoral studies ).

In the late portion of the fall semester of 1934, Beukema (like most professors) was trying to determine the readings for his spring semester classes. Beukema determined that cadets needed to study President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs because of the significant role the programs and policies were having on the nation’s economy and society in general. On November 28, 1934, Beukema submitted a routine memo requesting the temporary adoption of The New Deal in Action by Schuyler C. Wallace for use in the Economics course for fourth-year cadets (seniors). At the time, a professor would submit this type of request to the General Committee, which was an academic committee made up of nine professors representing the various departments. The General Committee would then forward their recommendation to the Superintendent for his approval.

The New Deal in Action was not written by any leftist firebrand. Wallace was an associate professor of public law at Columbia University and would have a stellar academic career, including training U.S. Navy officers for military governance in the Pacific in World War II. It is safe to say that Dr. Wallace was not advocating for radical changes in the nation’s economy in his book. Beukema stated in the memo that he had examined “a considerable number of books covering the New Deal… [and this one] presents the best and simplest factual survey of the subject.” Furthermore, Beukema reminded the General Committee and the superintendent that cadets had already examined the New Deal the past year using numerous articles and a pamphlet by Howard S. Piquet (Outline of the “New Deal” legislation of 1933). Two weeks after Beukema’s submission, the General Committee agreed to the recommendation and sent the request to the superintendent for his approval.

While the General Committee approved the request to use the book, there was some dissent among the members about the inclusion of the book (and the subject matter in general). Colonel C.C. Carter, Professor of Natural & Experimental Philosophy, felt that the Wallace book provided “a one-sided presentation, if not a partisan one.” Also, he argued that cadets should not have their first taste of economics clouded with a large amount of time dedicated to a “particular controversial phase of current events.” While Colonel Carter did feel that cadets should be educated on the issues of the day, he felt that this book was too partisan to be used at West Point. Colonel R.G. Alexander, the Professor of Drawing, wrote “I concur” on Carter’s letter with no further details. Lieutenant Colonel C.L. Fenton, the head of the Department of Chemistry and Electricity, mirrored Carter’s arguments in a memo dated December 14, 1934, where Fenton described the book as a “highly colored, incomplete presentation of one side of the question.”

As an academic and seasoned bureaucrat, Beukema addressed the criticisms of the book in a memo dated December 17, 1934, directed to the members of the Academic Board. The three-page memo provided detailed responses to the Academic Board members’ criticisms of the book. Beukema even included specific sections of the book that were critical of the New Deal. Beukema also reminded the Academic Board members that the cadets at the academy regularly studied current events “considered too important to be ignored or underestimated.” Furthermore, Beukema took offense to the Professor of Chemistry telling him (the chair of the Social Sciences Department) what to cover in the Economics class and stated that the “New Deal is a subject of study at all leading colleges and universities today.” Lastly, Beukema argued that the department had selected a book that stayed sufficiently neutral to develop a sound discussion.

Not analyzing the New Deal and its impact on the economy would be akin to not studying Reagan’s “Trickle Down Economics” in the 1980s or the economic facets of the Space Race in the 1960s.

Even though Beukema crafted an eloquent defense of the use of the book, Major General William D. Connor, the Superintendent of the Academy, denied its use because “the so-called New Deal is a live political issue and, as such, is not suitable for study or discussion in this institution. Second, the so-called New Deal is personally sponsored by the President, who is Commander-in-Chief of the Army, and whose policies are therefore not properly debatable in this institution.”

Beukema met with the Superintendent on January 2, 1935, to plead his case that you cannot teach modern economics, which Beukema argued was “wholly controlled by New Deal legislation,” without discussion of the New Deal. Major General Connor agreed to a compromise and allowed for the facts “flow[ing] from the law to be discussed in class. However, the New Deal policies are not to be the subject of debate. While Beukema did not get to use the book, he did get to teach the cadets about the New Deal.

Looking back, it’s hard to believe that Beukema had to struggle to educate his colleagues about the significance of the New Deal, which was one of the most crucial reforms in terms of government and economy during the 20th century. Not analyzing the New Deal and its impact on the economy would be akin to not studying Reagan’s “Trickle Down Economics” in the 1980s or the economic facets of the Space Race in the 1960s. Both subjects that were controversial at the time.

It is important for cadets and officers to have knowledge of current events and society to be effective leaders and soldiers in a democratic society. While some critics may have personal views on subjects, studying them does not mean being indoctrinated into a certain ideology. It is necessary for cadets and officers to understand modern social and cultural issues to lead their soldiers effectively, especially in an all-volunteer military. Military conflicts do not occur in a social and cultural vacuum, and leaders need to comprehend the causes of war. For instance, while the American Revolutionary War was primarily due to a desire for freedom in the colonies, there were also social, political, cultural, and economic undertones. In the Southern Campaign, people often chose sides for cultural reasons instead of political ones.

It is vital for military officers to have a comprehensive understanding of current events in American society in order to strengthen civil-military relations. They must be familiar with the life experiences of their soldiers to effectively lead them. Additionally, they should be knowledgeable about various political, social, and cultural movements without being influenced by them. Although the military remains nonpartisan, it is still important for them to be educated. In today’s world, where information, culture, heritage, and social media can be weaponized and used in irregular warfare, military leaders should be well-versed in traditional military science as well as understanding their own society and others.

Edward Salo, Ph.D. is an Associate Professor of History and the Associate Director of the Heritage Studies Ph.D. Program at Arkansas State University. Before coming to A-State in 2014, he spent 14 years as a consulting historian for various firms across the nation. His work has been published in War on the Rocks, The National Interest, 1945, InkStick, and by the Modern War Institute. He is also a host of the “Sea Control” Podcast, and a member of the New America Nuclear Futures Working Group.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Arkansas State University, the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

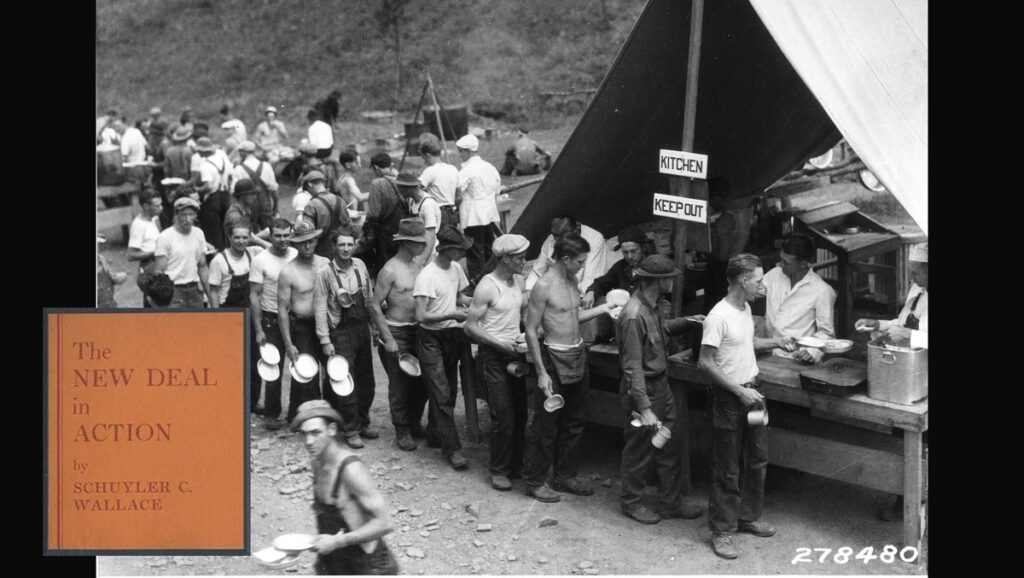

Photo Description: Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp mess line. The Civilian Conservation Corps was created as part of the New Deal in 1933 by FDR to combat unemployment. This work relief program had the desired effect, providing jobs for many thousands of Americans during the Great Depression. The CCC was responsible for building many public works projects and created structures and trails in parks across the nation that are still in use today.

Photo Credit: USFS photo #278480 from the Gerald W. Williams Collection via OSU Special Collections & Archives