Trường Chinh remains a revered figure in Vietnam, but today few scholars and national security professionals study his writings on revolutionary warfare.

Võ Nguyên Giáp, the Vietnamese communist general, is a well-recognized figure of the Indochina Wars that occurred in the mid-twentieth century. He is most famous for his victory over French military forces at Dien Bien Phu in 1954 during the First Indochina War (1946-54) between France and the Viet Minh Front, a Communist-led organization fighting for Vietnam’s independence from that colonial power. Giap is also renowned for his treatise People’s War, People’s Army, published in English in 1962, which provides his concepts of the strategy and tactics of guerrilla and revolutionary warfare and their application. Yet in that publication, Giap pays homage to another important figure in Vietnamese military affairs, Trường Chinh, who Giap credits for making “an important contribution to the thorough understanding of the Resistance War line and policies of the [Communist] Party” by providing a theory of war and strategy for the armed struggle and the development of the revolutionary armed forces. Trường Chinh remains a revered figure in Vietnam, but today few scholars and national security professionals study his writings on revolutionary warfare.

Trường Chinh was born Đặng Xuân Khu on February 9, 1907, Ha Nam Ninh province, Vietnam. He joined Ho Chi Minh’s Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth Association, the “cradle of communism in Vietnam,” in 1928, and participated in an anti-colonial strike that resulted in his arrest and expulsion from the local high school. He moved to Hanoi where he graduated from a lycée, enrolled in the School of Higher Commercial Studies, and worked as private a teacher but also pursued politics as a member of the newly formed Indochinese Communist Party (ICP). As the co-editor of a communist newspaper, the French police arrested him in 1930 for subversive activities, and the court sentenced him to twelve years of penal servitude. Paroled in 1936, he became a member of Ho’s inner circle because most of the party’s early leaders were dead or exiled. In 1941, he surfaced as the ICP’s general secretary and ultimately, its leading theoretician. Around this time, he adopted the pseudonym Trường Chinh (“Long March”), in tribute to Mao Zedong’s famous military retreat during the Chinese Civil War.

In late 1947, with the First Indochina War now ongoing with France, Trường Chinh published the book Giap alluded to: The Resistance Will Win. He borrowed freely from Mao’s teachings on guerrilla warfare and especially protracted war, often without attribution. In the view of historian William Duiker, it was the “first major exposition of Vietnamese revolutionary strategy since the formation of the Vietminh Front” in 1941.

Trường Chinh began his treatise by arguing that the current conflict was a people’s war “aimed at achieving national independence, democracy and freedom” from the French colonialists, while also an agrarian revolution through confiscating land and other property from Vietnamese landlords (“feudalists”). To accomplish these objectives, he specified four lines of resistance (effort): political, economic, cultural and military.

Political resistance necessitated mobilizing and uniting the entire people under the leadership of the national front to wage the war against the French and their Vietnamese “feudal” élite and “comprador bourgeoisie,” and to win material and moral aid from supporters in the international arena. Economic resistance would destroy the colonial economy through sabotage while building a self-reliant Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) economy. Lastly, cultural warfare could break the bonds of French culture, using art and literature to propagandize and enlighten the masses.

Trường Chinh emphasized that the conflict was “political struggle” based on socio-political mobilization, but the book’s main emphasis was on military resistance. Military resistance entailed a strategy of protracted war because the balance of forces at the moment favored the French. Time was the “best strategist,” he wrote—time to organize, train, and learn tactics. Additionally, the lengthier the war, the more likely the French population would become demoralized, revolutionary movements in other French colonies would emerge and require the government to spread its forces to quell rebellions, and world opinion would turn against France.

The character of this war in the early days was one without “battle-fronts,” i.e., an interlocking of conventional and guerrilla warfare using both hit-and-run tactics as well as isolating and destroying smaller enemy forces when the situation permitted. However, long-term resistance required the buildup of a regular army to attack the enemy’s front, guerrilla forces to attack the rear, and militia for regional self-defense and as a reserve for the regular army. Long-term resistance demanded resilience, but a more sophisticated military strategy, too.

Given the war’s character and his assessment of the difficulties, strengths, and weaknesses of each side, Trường Chinh specified that the military strategy of resistance had three stages, although there was no clear dividing line between them: defensive stage, stage of equilibrium, and stage of general counteroffensive. The enemy’s strategy in the first stage was offensive: to control cities, lines of communication, and where possible, large areas with its preponderance of forces and capability; and to sow discord between the Viet Minh and the people. The front’s strategy was defensive; use guerrilla tactics in the cities and countryside to attack constantly and retreat into safe areas. As the enemy advanced from the cities, it extended its lines of supply and communication (war of position), thereby creating opportunities for the front’s regular forces to stop the advance and encircle the enemy, exploiting tactical surprise or local superiority (mobile/maneuver warfare), while guerrilla warfare continued.

Trường Chinh warned that this stage, [equilibrium,] was complex, difficult to execute, and required time, but was critical as it was the stage that allowed the front to advance to the next phase.

The stage of equilibrium occurred when the two forces became relatively equal; absolute superiority was not a prerequisite. The enemy was now on the defensive without the strength to advance, but determined to consolidate its positions and communications lines by conducting “mopping up” operations and restoring political order in occupied areas. The front, however, prepared for the general counteroffensive: training cadres, building even more conventional and guerrilla forces, and developing revolutionary organizations. Additionally, it executed local attacks in enemy-occupied areas to harass and exhaust the enemy, counter its operations, commit sabotage, and destroy enemy units piecemeal. Guerrilla warfare predominated, but regular forces trained guerrillas and conducted mobile warfare when the situation allowed. Positional warfare, that is, static frontlines and large-scale combat operations, supported the other two forms of warfare. Trường Chinh warned that this stage was complex, difficult to execute, and required time, but was critical as it was the stage that allowed the front to advance to the next phase.

In the counteroffensive stage, the balance of forces now favored the Viet Minh because protracted war had drained the enemy’s morale and capability in Vietnam and metropolitan France. Tactically, mobile warfare campaigns played the first crucial role, with regular forces and large guerilla units acting as regular forces, but eventually evolving into positional warfare. Faced with defeats, the enemy retreated into the cities and strong points, which the Viet Minh attacked constantly to encircle and annihilate the enemy. This stage, although the briefest, brought decisive victory.

The conflict, he reiterated, was in the defensive strategy currently, consequently the ill-trained Viet Minh must optimize its guerrilla warfare advantages (e.g., climate, terrain, and population), defend important positions, and take the initiative to lure and harass, attrite, and whenever possible, annihilate the enemy locally. Equally important was forming a regular army and militia for the next stage, which would arise eventually. However, discerning the moment to move to this stage called for sound judgment and analysis: “when our leadership is skillful we can take advantage of favorable conditions of our time and situation.”

As one of the leaders, Trường Chinh influenced the strategy’s implementation as well. By 1951, he held that the Viet Minh should prepare for the counteroffensive as the strategic environment had changed with the Communist victory in China and a crumbling French empire. Likewise, the balance of forces was now in the DRV’s favor. It had substantial Sino-Soviet assistance, to include Chinese military advisors, formed a capable regular army of divisions with essential command and control and support elements, and mobilized the society. Unfortunately, Giap made tactical blunders in 1951 and 1952 when he attacked superior French forces that crushed his units. But Giap learned and loyally followed Trường Chinh’s strategy that led to success at Dien Bien Phu.

In the early 1960s, as the U.S. Army and Joint Staff developed its broad doctrine on counterguerrilla operations in response to the emerging national wars of liberation, it fixated on the writings of Mao and Giap for background. Bernard Fall pointed out, however, in Primer for Revolt (1963): “It was Trường Chinh, rather than Mao, that Giap read as he prepared his first offensive against the French, in 1951.” A few years later, the Central Intelligence Agency recognized Trường Chinh not only as the mastermind behind France’s defeat, but detailed how the North Vietnamese were applying his strategy in the ongoing Vietnam War. Yet, it is not apparent that the military used this insight to fashion its military strategy to avoid the strategic and tactical errors the French committed.

Sun Zi’s dictum, “If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat,” proved fitting. The preoccupation with Mao and Giap was understandable but was misguided; the military read the wrong strategist. Trường Chinh made use of Mao’s model of protracted war, but he deviated from it in two important ways regarding the operational and strategic environments. First, China’s geographical vastness was not mandatory for success; extensive and secure base areas for guerrilla operations could be established within the small country of Vietnam. Second, declining public morale and sympathetic world public opinion had outsized influence. Political and diplomatic efforts supported military power to achieve victory at the negotiating table or on the battlefield. In the First Indochina War and the Vietnam War these factors proved decisive.U.S. intelligence analysts recognized Trường Chinh’s impact on North Vietnamese military strategy. However, that knowledge did not result in the formulation of an effective U.S. counterstrategy. There is an important lesson here for policymakers and military leaders: development of a theory of victory to counter an adversary’s strategy requires an appreciation for specific strategic and operational contexts. Moreover, its formulation demands more than reading texts to devise generic doctrine. It deserves careful and immersive study of the enemy’s culture and theory of warfare to respond effectively. The army’s development and implementation of AirLand Battle doctrine against the Soviet Union is an apt example and one worth emulating as it seeks to address immediate threats and pacing challenges.

Frank Jones is a Distinguished Fellow of the U.S. Army War College where he taught in the Department of National Security and Strategy. Previously, he had retired from the Office of the Secretary of Defense as a senior executive. He is the author or editor of three books and numerous articles on U.S. national security.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

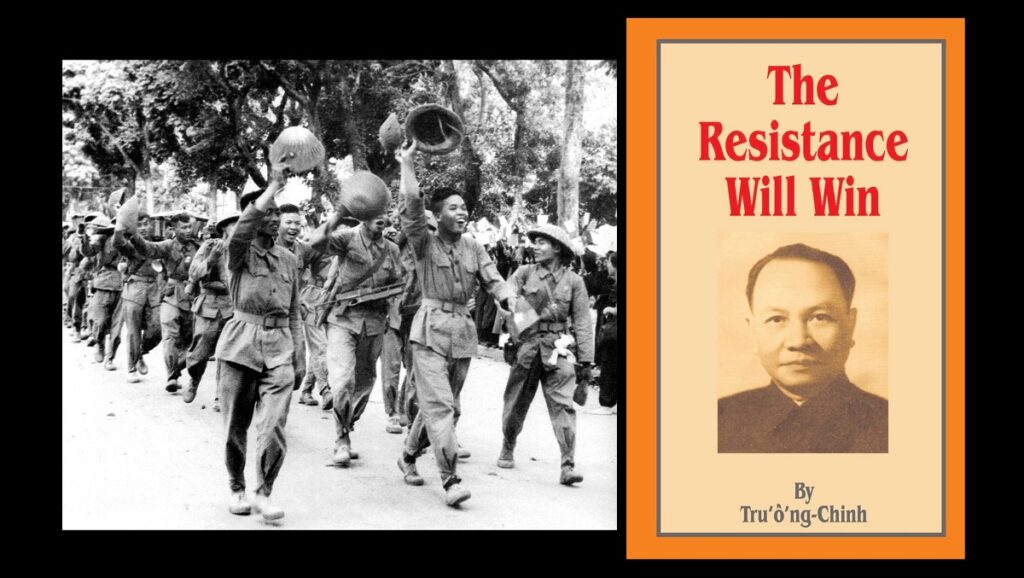

Photo Description: October 9, 1954. Waving to the city’s populace, joyous Viet Minh troops enjoy a “parade of victory” through the streets of Hanoi following the French withdrawal. Thousands of Vietnamese civilians crowded the capital’s streets waving flags, cheering and throwing flowers to the crowd of soldiers at the end of the French Indochina War.

Photo Credit: George Esper, The Eyewitness History of the Vietnam War, Associated Press 1983