It is essential therefore that universal training be instituted at the earliest possible moment to provide a reserve upon which we can draw if, unhappily, it should become necessary.

—Harry. S. Truman

In the waning days of World War II, there was a debate among the War and Navy Departments, Congress, the White House, and the national press over the need for universal military training (UMT). With the war in Europe over but fighting ongoing in the Pacific, the U.S. military jointly recommended the adoption of UMT to improve military readiness. Similarly, the new president, Harry S. Truman, advocated UMT as part of a program to strengthen “the Nation’s long-range security.” While often conflated with “universal military service,” UMT is significantly different and deserves a reexamination to prepare the U.S. for current security challenges posed by Russia and China. Current military and civilian leaders would do well to consider the nation’s initial unpreparedness to fight World War II. The United States should re-evaluate the potential benefits and drawbacks of UMT, and the steps needed today to increase our national preparedness and deterrence in an uncertain security environment.

What UMT is and is not.

The concept of UMT is not new. Shortly after the nation’s founding, General Henry Knox, the first Secretary of War, advocated the training of militia to serve as the wartime contingency to the small-standing army. The Militia Act of 1792 did not include this training requirement, which meant during wartime, volunteer militia entered active military service with little baseline training and caused delays in creating ready units. History has repeatedly shown that the call for volunteers and the creation of new units takes time and increases what we today call military strategic risk (or military risk) for the nation. In the early-twentieth century, many Americans were outspoken about the nation’s unpreparedness as they watched Europe embroiled in the Great War. The national outpouring of concern led to the Preparedness Movement and the creation of officer training camps in response to the possible involvement of the United States in the war. Since World War I, the U.S. form of universal military service has actually been “selective service,” a draft in which candidates are called up and screened, ensuring that those individuals who meet certain standards are conscripted into the military. This allows individuals with critical skills necessary for the economy and national defense to serve the nation through working in mining, industry, and other needed occupations.

Universal military training is predicated on the idea that a small peacetime military cannot rapidly expand for large-scale combat operations against a peer competitor without a large body of trained citizens to draw from. The risk due to the time gap from the start of a declared national emergency to having trained personnel to serve in newly created formations is too great. A key issue with initiating selective service at the beginning of a crisis is that it will take the U.S. Selective Service System at least 6 months to induct the first person into the military after Congress passes and the president signs legislation calling for a draft. Place on top of that required basic and advanced individual training (AIT), it will be over a year before these service members can form new units or fill out those requiring replacements. Can the nation wait this long to rapidly expand its military in the event of large-scale combat operations that will generate large numbers of casualties?

Even after the challenges of mobilizing the army for World War I, UMT failed to make it into the National Defense Act of 1920 and the United States found itself again unprepared when World War II began in 1939. The war in Europe and tensions in the Pacific led the United States to implement selective service from 1940 through 1945. The Army saw a massive expansion of its active-duty end strength from 269,023 to over 8,000,000. This unprecedented growth of manpower caused second and third-order effects due to the challenges of training, equipping, and fielding operational units. Although personnel in those quantities may never be needed again, the combat losses taken by both Ukraine and Russia over the last two years have required both nations to mobilize their populace.

The Universal Military Training concept published by the War Department on 25 August 1944 and jointly with the Navy in May 1945 suggested that all young men complete one year of military training after finishing high school and before entering the workforce or higher education. Those sent to the army would complete basic and AIT, learn to operate in their military specialty within a training unit, and then complete realistic, large-scale combined arms maneuvers. For Navy and Marine Corps trainees, this final phase would include serving onboard ships and conducting amphibious operations. After one year of training, these men would be released to their peacetime pursuits and remain in a “Citizen Reserve” for five years. During this period, they would only be subject to recall in a national emergency declared by Congress.

In 1947, the Army created a UMT pilot program at Fort Knox, Kentucky with the goals of validating the concept and highlighting its benefits to the nation. There was valid criticism that the army stacked the deck by selecting above-average inductees (by qualification standards) and placing extra resources of staff, trainers, and facilities for one test battalion (commanded by a brigadier general). Results were unsurprisingly positive and additionally, the army’s active-duty 3rd Armored Division at Fort Knox implemented elements of the UMT training program, validating the concept of creating UMT Training Divisions to conduct collective training during their one year of service. Despite the positive results from the pilot program, UMT did not come to fruition.

By 1948, the campaign to implement UMT failed for a variety of reasons. The Cold War with the Soviet Union was getting hotter, as tensions were increasing in Europe. The cost of the European Recovery Program (Marshall Plan), including the buildup of the newly independent Air Force and its role in national defense, led to Congress not passing the UMT bill but rather the Selective Service Act of 1948, implementing continuous selective service to bolster the increased manpower requirements for a large standing Army. Regardless of its demise, it is worth reviewing UMT’s benefits and possible drawbacks, and value for today.

[I]n today’s security environment, a nation’s ability to mobilize its populace and industry in the face of aggression is a means of deterrence.

Benefits

Supporters viewed UMT as a means to increase deterrence by maintaining a general reserve of trained men that could rapidly increase force structure in times of national crisis. This would allow the United States to maintain a small, peacetime active-duty force and reduce the need for selective service to fill a large standing army. Supporters of UMT foresaw the unpopularity of continuous selective service that rocked the U.S. during the late 1960s during the Vietnam War. Having a large general reserve, like the Individual Ready Reserve, would speed up mobilization in the event of a national emergency. Speed is relative, but as mentioned earlier, having a replacement in months rather than a year improves readiness. Military leaders such as General George C. Marshall believed that UMT, along with an economy geared toward defense production, would have deterred the start of World War II.

Similarly, in today’s security environment, a nation’s ability to mobilize its populace and industry in the face of aggression is a means of deterrence. Recently, retired Australian Major General Mick Ryan wrote that [mobilization] “is a statement of will. The development of a mobilization plan, much less its implementation, is a demonstration of will by a government and a nation.” Marshall and Truman realized this eighty years ago and the principle is valid today. The United States and its allies need to demonstrate the ability to rapidly expand the peacetime-sized military in the event of a national emergency. Without having a viable general reserve of trained personnel, the costs to the nation may be too great to bear. Universal military training is not truly “universal” for every 18-year-old man or woman in the nation. A strong and healthy economy requires men and women to also serve in the public and private sectors in a multitude of occupations that support the nation. The size of the UMT program must be informed by the cost of maintaining a general reserve against the level of deterrence it provides while maintaining a robust economy.

An additional long-term benefit of UMT is that it addresses the decoupling of the military from American society. This program will expose more citizens to military service, and in turn allow them to pass on its virtues in communities across the country, helping to decrease the gulf that currently exists. Other benefits of UMT include serving as a pipeline for those who wanted to continue to serve on active duty, or part-time in the National Guard and Army Reserve. It also served as an access point for the path to becoming officers through ROTC and attendance at the service academies.

Finally, some may believe that having a large body of trained soldiers only available for a national emergency may not be worth the cost of training that force and maintaining them “just in case.” The UMT option will require additional active-duty end strength to serve in the institutional Army to train, and then lead the organizations required to conduct collective training. This workforce comes at a cost to operational units supporting existing or contingency operations. With a budget failing to meet readiness and modernization requirements, this additional burden may not be worth the cost.

A First Step Forward: (A New) UMT Pilot

A shift from the current all-volunteer force to UMT would be an enormous shift for not just the military but the country as a whole. To help both the DoD and public understand some of the consequences, both positive and negative, the army should borrow an idea from the 1940s and seek approval to conduct a limited experiment of a short-term training period (six months to a year) followed by five years of service in a general reserve or Individual Ready Reserve status. Dr. Andrew Hill and COL Paul Larson recommended something similar in recruiting soldiers for a one-year active-duty commitment followed by up to ten years in a Modified Individual Ready Reserve. For the army, a realistic target for this pilot is 9,400 soldiers a year, providing a 47,000-soldier general reserve after five years. This equates to five percent of the AY25 Total Army’s military end-strength of 943,100 soldiers. Possible incentives for those selecting this option are offering modified benefits via the various existing GI Bills or health care options similar to those offered by the Army Reserve or National Guard while serving in the general reserve. The benefit of this option is to build a capacity over time that would deter potential adversaries from threatening the United States and our way of life.

Piloting UMT will require showing the American people that this concept is both required for deterrence and beneficial to the nation. Military advertisement campaigns have always touted the ability to serve the nation and learn new skills. The UMT path provides a slight twist on the existing Army Reserve and National Guard path. The military must market itself to those Americans who desire certain skills but do not want active or reserve duty service connected with the existing paths. Seek out this population who want to learn skills needed by the military (e.g., truck driving, welding, information technology etc.), and then assign them to the general reserve. The original UMT model sought 17 through 20-year-olds for training. By opening the age range to 25 years of age, you can also target those who are seeking a career change. The incentive for the commitment is civilian workforce training, with the added benefit of discipline, and esprit de corps offered by the military plus the benefits listed above. Possible enticements for service in combat arms skills could be improved benefit packages. There is also the incentive to speed up the path to citizenship through serving in UMT.

A pilot UMT will not solve the current personnel issues for the AVF and may initially take away from it. There is the chance that those with the propensity to serve may choose the short-service option over serving on active duty or in the Army Reserve or National Guard. For several years, the Army’s requirements have exceeded the available active-duty end strength. Although the inability to recruit seems to be abating, the precipitous drop in overall end strength over the last few years will take time to correct. What the DoD can do is reevaluate what the true requirements are and either seek Congressional approval to increase end-strength or reduce requirements.

UMT will increase the burden on the institutional Army to conduct initial and advanced training and cadre organizations required to conduct collective training. To mitigate the drain on manpower away from the operational force, the army can leverage existing occupational training of potential candidates. With an age range of 17-25 year olds, the service can take advantage of men and women already qualified with skills required by the army and provide them with a short but intensive period of individual and collective training before being assigned to the general reserve. The army needs to be innovative and forward-looking, seeking skills for the wars of the future and not just the past. Robotics, drone operators, and possibly even first-person gamers are needed skills, as seen in Ukraine today. These men and women can have the additional benefits of possible student loan repayment. Logistics, information technology, and healthcare fall into this category also. This path is like the Direct Commissioning program for chaplains, lawyers, medical providers, logisticians, cyber experts, and other critical officer specialties. During World War II, over 100,000 civilians were direct commissioned into the military with these and other technical skills and backgrounds. The benefit of this program creates Soldiers with the needed skills who require less time in the training pipeline, thereby reducing the overall costs to improve deterrence.

The world is at a perilous point with ongoing wars in Ukraine and the Middle East, and rising tensions in the South China Sea. The United States is scrambling to rapidly reinvigorate its industrial base and modernize its military with the most lethal equipment and new technologies. Yet without trained men and women in these formations, readiness is impacted, and the nation is unprepared. Mobilization of personnel is a form of deterrence and UMT is a first step in the right direction.

Douglas Orsi is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Command Leadership and Management (DCLM) at the United States Army War College. He is a retired Army colonel who has written previously on professional military education and mission command.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, Department of State or the Department of Defense.

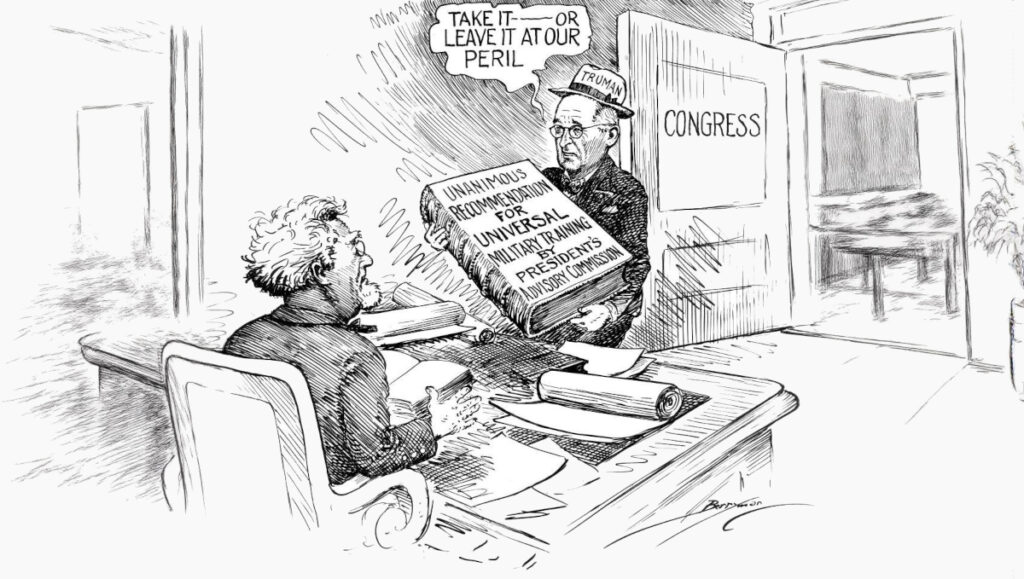

Photo Description: President Harry S. Truman’s advisory commission sent a proposal to Congress for a program intended to stop Soviet expansion in Europe and to rebuild Western Europe’s economies that were destroyed during the war. The proposal included military aid to Greece and Turkey, and universal military training for American men 18 years old and over. The commission believed universal military training would support the US’s threat to defend Western Europe from soviet aggression. June 3, 1947

Photo Credit: Berryman Political Cartoon Collection via the National Archives Catalog, image expanded via Fotor AI.