As G.K. Chesterton wisely observed, “The true soldier fights not because he hates what is in front of him, but because he loves what is behind him.”

“Task” and “purpose” are two of the most foundational doctrinal terms in the U.S. military, yet it seems that while tasks are usually clearly articulated, purposes are often treated as an afterthought or neglected altogether. But purposes provide the moral foundation from which all military action is derived and are therefore critical to success in war. As G.K. Chesterton wisely observed, “The true soldier fights not because he hates what is in front of him, but because he loves what is behind him.” However, if servicemembers are never taught what is loveable about that for which they fight then there should be no surprise if they fail to fight well. This is especially true for a nation with such a rich heritage of national purpose as the United States, founded as it is on sacred truths. Leaders should seize every opportunity to reinforce these truths that constitute America’s national purpose.

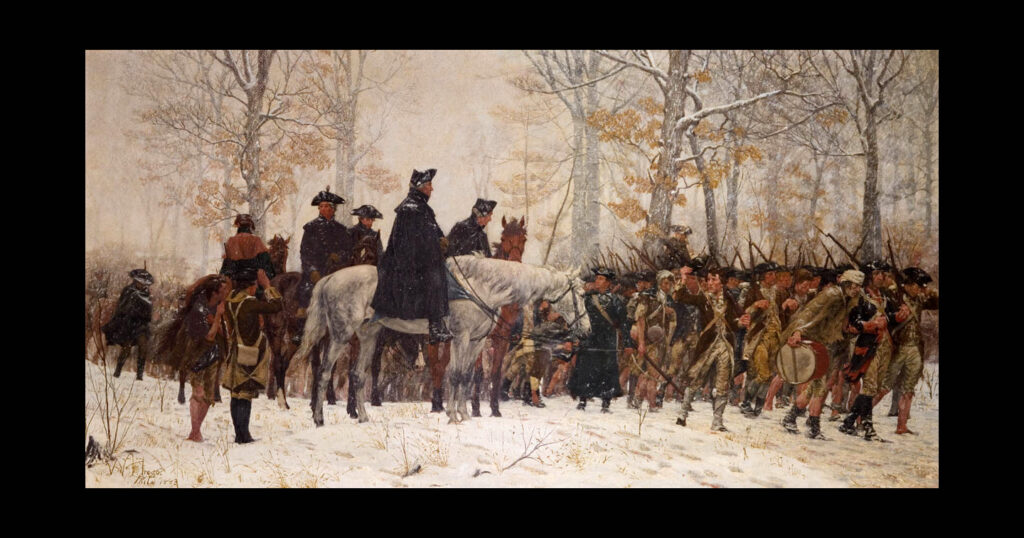

When George Washington, who intimately understood this connection between purpose and what J. F. C. Fuller called “the moral sphere of war,” assumed command of the Continental Army, he did so because of he genuinely believed in “the glorious Cause.” This commitment to the cause or purpose, in modern English vernacular, would become the driving force behind his tenacity, endurance, and leadership style. Washington knew that soldiers would endure the hardships of war only if they were given a clearly defined and objectively good purpose. They deserved a cause worth suffering for.

Five months after he assumed command, Washington reiterated the centrality of purpose to an effective fighting force, when he counseled a newly commissioned colonel to “impress upon the mind of every man, from the first to the lowest, the importance of the Cause, and what it is they are contending for.” A commander-in-chief with less appreciation for the moral sphere of war would have confined his concern for subordinates’ understanding of national purpose to key leaders. But Washington understood the power of a well-articulated national purpose to inform and influence behavior at all levels, including the tactical.

While national purpose may have little or no effect on tactical decisions such as whether to seize hill “X” or “Y,” Washington did not doubt its ability to instill courage in the hearts and minds of each soldier, regardless of rank. The moral assumptions embedded in that purpose, which in turn shaped his army’s organizational culture and standards of behavior, acted as a lens through which soldiers were to view the conflict and the character of the new nation. It did not specify tasks but reinforced the collective will of the Army to endure until it achieved a satisfactory outcome.

A year after he assumed command, the Continental Congress gave Washington the perfect tool for articulating that cause to his soldiers in the form of the Declaration of Independence. The Declaration grounded the Americans’ fight for liberty in universal truths, applicable to all peoples at all times and in all places. Armed with ultimate purpose, articulated and approved by the ruling body of the land, Washington ordered that the document be read aloud to his army in the hopes that it would clarify the great national end for which his soldiers sacrificed and inspire them to fight courageously.

The Power of Purpose

Purpose is a powerful force bordering on the transcendent. It puts steel in one’s spine and acts as an antidote to suffering. Purpose makes warriors out of cowards and patriots out of pacifists. It directs the aimless, and with such certitude comes a quiet peace and confident humility. “Courage,” Walter Grady observes, “requires the support of a purpose.”

Purpose plays a similar role in the success of organizations, armies, and nations. Napoleon’s famous observation that “in war the moral is to the physical as three is to one” encourages the warfighter to prioritize purpose as a key element of combat power. Napoleon was far from saying that the physical does not matter, but capability and capacity mean little unless there is a will to use them. That will is forged through understanding and acting according to a worthwhile purpose.

When Washington assumed command, his great challenge was to galvanize disparate state militias around a national purpose and to direct their individual and unit-level actions toward national victory rather than defense of their individual states. He did not eschew soldiers’ natural instincts to fight for self-preservation, camaraderie, and glory, but he subsumed those instincts into a collective will to endure for the sake of the country as a whole. He used the words and principles of the Declaration of Independence to do so.

Washington and Lincoln’s articulation of national purpose informed soldiers’ relationships to what Grady refers to as “absolutes,” which are the foundational moral reasons for fighting.

Purpose Still Matters

The use of the Declaration of Independence to direct the U.S. military to national ends did not end with Washington. Abraham Lincoln inherited this conviction and applied it to his particular circumstances. President-elect Lincoln hoped that the Union might still be saved upon the basis of a shared understanding of liberty as expressed in the Declaration. A couple of bloody years later, he reminded the country and its soldiers that their purpose was to preserve a nation “conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

Washington and Lincoln’s articulation of national purpose informed soldiers’ relationships to what Grady refers to as “absolutes,” which are the foundational moral reasons for fighting. It cultivated a sense among soldiers that they were no longer responsible only for their own survival and that of their families, but also for the very soul of the country. Major Sullivan Ballou, a Union officer killed at the First Battle of Bull Run, exhibited this understanding in his last letter to his wife:

I have no misgivings about, or lack of confidence in, the cause in which I am engaged, and my courage does not halt or falter. I know how strongly American civilization now leans upon the triumph of government, and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the Revolution, and I am willing…to lay down all my joys in this life to help maintain this government, and to pay that debt.

When America asks her sons and daughters to fight, bleed, and die, she should always provide such a clear and worthy purpose.

Rediscovering Purpose

Two hundred and forty-seven years after Washington assumed command, General Mark A. Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, admonished the graduating class of the United States Military Academy that they must be prepared to “make the right moral and ethical choices, along with the right tactical choice in the most emotionally charged environment you will ever face.” They must demonstrate “the willingness to disobey specific orders to achieve the intended purpose” and “to take risks to meet the intent.” But when leaders make these demands they must also work to furnish the moral framework within which decisions are to be made. Whether morality is objective or subjective, socially constructed and relative or universal and timeless, it has a direct bearing on how those young leaders will make ethical decisions under intense pressure.

It may be argued that such grand philosophical and moral ideas are the purview of statesmen and generals and that junior officers and enlisted need not be concerned with such matters. But according to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, this generation of servicemembers will see small elements separated from higher echelons by vast distances in which the senior-ranking officer is a lieutenant. Unlike previous great power wars, in which general officers maintained close and direct control of their formations, command and control on the future battlefield will place a high premium on autonomy and, consequently, on trust, integrity, and moral reasoning. There is no question that these servicemembers require a deep understanding of a sound overarching purpose, grounded in immutable moral principles. Just as Washington did for his army, today’s military leaders must do everything in their power to provide such a purpose.

Conclusion

In his 2012 study on the use of foundational American documents for moral education, Chaplain Ryan Rupe set out to determine if it was still feasible and effective to use the Declaration of Independence as a means for teaching virtue ethics, just as it had been for Washington and Lincoln. Chaplain Rupe gave a block of instruction centering on the Declaration to fifty Coast Guard officers, enlisted, and civilians. He concluded from the feedback he received that the meaning and principles of the Declaration still resonate in the consciences of servicemembers when they are exposed to it. However, occasional blocks of instruction are not enough to translate national principles into moral imperatives that drive behavior. This requires constant and intentional engagement from leaders at all echelons.

To that end, leaders should seize every opportunity to reinforce the sacred truths that constitute America’s national purpose. Every equal opportunity briefing is a chance to explain that all people are created equal and therefore possess an inherent right to fair treatment. Every sexual harassment and assault prevention presentation is a chance to remind servicemembers that everyone possesses the right to pursue meaningful happiness and that sexual aggression is the grossest infringement on that right. Every safety brief, change-of-command ceremony, and graduation is a golden opportunity to refocus on those principles for the support of which we pledge “our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.”

Andrew J. Bibb is a strategic plans and policy officer in the Army Office of Business Transformation who has deployed to Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, the Arabian Peninsula, and Latvia. His work has been published in respected outlets including the Modern War Institute at West Point, Small Wars Journal, 19FortyFive, and the U.S. Congressional Record.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Painted by William B.T. Trego

Photo Credit: George Washington leading the Continental Army to Valley Forge in 1777.