The doctrinal idea of mission command might be usefully compared to how a quarterback calls a play but through trust and preparation the receivers will have the latitude to get themselves open for a pass if the play breaks down.

Army War College students love sports. Each year as seminars form and students introduce themselves to each other, it is not uncommon for them to name a favorite team. Throughout the year when dialogue occasionally falls flat, attention will turn to the previous night’s game. And the War College infuses sports into the social fabric, from seminar softball to the Jim Thorpe Sports Days against the other war colleges.

Perhaps inevitably, sports infiltrate into classroom content as metaphors. The doctrinal idea of mission command might be usefully compared to how a quarterback calls a play but through trust and preparation the receivers will have the latitude to get themselves open for a pass if the play breaks down.

But sports metaphors—like all metaphors—have their limits. Once during a comprehensive exam, a student who was a professed sports junkie tried to describe near-peer competition as a heated on-field rivalry like the Yankees and Red Sox. While at first glance this metaphor may seem to align well, it failed to hold up during the question-and-answer phase because the rules of the game of baseball are pre-established. Unlike in a near-peer relationship, baseball teams do not get to negotiate the rules with each other.

What entered my mind as I listened to the student was that the wrong rivalry was being invoked. Rather than the Yankees and Red Sox, what about Major League Baseball (MLB) versus the National Football League (NFL)? Both are prominent businesses whose challenges mirror those of the military. The games are very different but both leagues vie for revenue, fans, national attention, and available time slots on television and media.

Perhaps this is indicative of an opportunity being missed. While the common game-related sports metaphors sound good and generate emotional responses, they do not align well with the challenges, complexities, and tough decisions found in the strategic environment that War College graduates will encounter. While administering our end-of-core curriculum comprehensive examinations, the experience inspired some thoughts on other sports metaphors and models that can help national security professionals.

Strategic competition

The MLB and NFL, two leagues based in the same country, are but one of the many types of competition that goes on in the sports world. There is competition between international sporting events such as the Olympic Games versus the World Cup seeking dominance in revenue, audiences, and participation among member nations. For example, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) criticized recent decisions by the Fédération Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) to pursue holding the FIFA World Cup biannually vice every four years. IOC charged that FIFA’s move would cram the international football schedule and harm national participation in future Olympiads. But they also cooperate to an extent, or at least they enact common perspectives on world events. Consider systems of international order, as evidenced by these bodies’ decisions to expel Russia from their competitions over their invasion of Ukraine. Complicated relationships such as IOC-FIFA could provide a lens with which to understand the equally complicated landscape in the global security environment, such as between nations or among alliance and other international organizations such as the United Nations.

The competitive landscape within a sport can also help explain some strategic leadership and defense management concepts. Consider how the management of baseball has evolved. MLB (which did not exist before 1999) used to be two separate unincorporated leagues playing baseball under slightly different rules (e.g., one league using the designated hitter, the other not) overseen (since 1921) by a central, but weak, Office of the Commissioner. Over time, the Commissioner became more empowered, collective bargaining became unified, and interleague play began as an exception to the schedule and later an integral part of the schedule. The creation of MLB facilitated the full merger of the two leagues and institution of one set of game rules (e.g., mandating the designated hitter). However, this evolution was long and contentious owing to the entrenched identities of the two leagues. For military officers, the parallels to the challenges of achieving jointness are clear as forces for centralizing common functions at the joint or defense level have long conflicted with entrenched service identities. The strengthening role of the baseball commissioner could also serve as a lens for examining the growing prominence of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs.

The War College also includes negotiating as a critical strategic leader competency. Sports management includes examples of both successful and contentious negotiations that illustrate Roger Fisher and William Ury’s framework for negotiations such as separating people from the problem and establishing interests over positions. Two examples illustrate the negative. The 1982 NFL players’ strike began as a disagreement over salaries and free agency but degenerated into a personal feud between the chief negotiators of the players and owners and set the stage for another strike five years later. The National Basketball Association (NBA) owners successfully used artificial deadlines to coerce the players’ union to agree to unfavorable terms multiple times only to see future negotiations become more contentious, resulting ultimately in multiple work stoppages. In contrast, the growing concern over concussions and the negative impacts on both players’ health and the integrity of the sports has led to numerous leagues successfully negotiating concussion protocols. These negotiations are difficult and contentious, not unlike those involved in bringing wars to a conclusion. There may be no finer example than the successful negotiation of the 1995 Dayton Accords that ended the war in Bosnia and established conditions for a sustainable peace. Military officers can potentially find themselves participating in such high-stake peace talks in future.

Recruiting pools

Competitions and leagues promote their sports beyond their on-field products. Youth sports help the development and self-confidence of participants, with lifelong benefits. However, such programs are not cheap, and access to them can be limited for low-income families. Hence, all the top professional leagues contribute money and equipment to youth programs to encourage children to learn and play the game. There is also a litany of non-profit organizations that promote sports. Baseball has a robust Little League system in the United States that includes the annual Little League World Series to showcase young talent. The Pop Warner leagues in American football and Hockey Canada are other examples.

The parallel to the military may be useful in understanding the current recruiting challenges that include shrinking pools of youth that are qualified to serve without a waiver, while those that do join are at increased risk of serious injuries due to today’s more sedentary lifestyles. Historically, gym class in schools played a significant role in growing and sustaining potential soldiers while also encouraging healthier populations. Yet mandatory physical education has declined significantly in the United States today, with budget constraints and pressures toward academic achievement often cited as contributing factors. In September 2022, the Biden Administration released a National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health that includes calls for increased “rigorous physical education requirements” and a “whole-of-society response” (p. 31) with responsibilities identified at federal, state, and local levels. What elements of the experiences of sport organizations can inform these and other efforts to improve the quantity and capabilities of potential recruits and reverse these disturbing trends?

Sports organizations and athletes have long been active in charitable works and nonprofit organizations.

Outreach and connections to communities

Sports also provides excellent examples of the benefits (and occasional pitfalls) of engagement and integration with society. Sports organizations and athletes have long been active in charitable works and nonprofit organizations. For almost a half century, the NFL has maintained a robust charitable relationship with the United Way that supports “health, education, and financial stability” of those in need. The NBA and MLB and other sports leagues have similar partnerships with charities. Individual athletes have also been highly charitable and established their own nonprofits, some more successful than others. Leagues may include incentives for their members to contribute to society such as the NFL’s Walter Payton Man of the Year award and the NBA’s Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Social Justice Champion Award. Research has shown how these efforts help sports leagues to better know their communities and are ultimately good for the sports leagues’ bottom line in the long term.

What can the military learn from these activities? Consider the recruiting crisis of the early 2020s. The traditional approach to recruiting has involved separating the recruiting force from the operating force, ostensibly not to distract serving members from their readiness requirements. However, this may no longer suffice and the military may need to emulate how sports capitalizes on personnel connections with its fans. To its credit, the U.S. military is involving established social media influencers to reach its recruiting base, but broader cultural changes may be needed and sports organizations may provide clues for potential solutions.

On the other hand, sport leagues and athletes have had to contend with a wide range of scandals and embarrassments both on and off the field. Contemporary crises have revealed major problems with traumatic brain injuries, domestic abuse and other criminal behaviors, and corruption scandals and cheating. Crises also arise from statements on social media or during post-game interviews when athletes or coaches may be disappointed in the results or angered at a referee’s blown call. All the major sports leagues have established extensive crisis management systems, some touted for their successes.

These mirror existing problems in militaries, such as concerns over growing extremism in the ranks, toxic leadership, leaks of classified documents, and others. While sports organizations and militaries operate in different environments, for instance one operating in the private sector and the other in the public, sports organizations have been quite successful at crisis communications in ways that the military could adopt. Also, as sports have instituted cultural change over the handlings of concussions and mental health concerns, the lessons could be equally valuable in the military as it faces emerging threats of thermobaric weapons and the potential benefits of employing “first aiders” during operations to institutionalize the prevention of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Innovation

One can also look to sport to study innovations, and not just technology. Examples of important innovations that changed the character of sports include baseball gloves (invented in the 1890s), football’s penalty flag (1940s), and basketball’s shot clock (1950s). Today, technological innovations have infused playing equipment, training regimens, automated officiating, and fan engagement across nearly all sports. For example, the original XFL introduced the “sky-cam,” a robotic overhead camera that the NFL later adopted in its television broadcasts to enhance the viewing experience of fans. The modern incarnation of the XFL now has a deal with the NFL to conduct experiments on innovations that the NFL might adopt in future.

Organizing for innovation is a continuous challenge for militaries, whose history is replete with examples of great successes and incredible failures. In the past decade, the DoD has launched efforts to develop and implement tools for innovation with some success, relying on partnerships with commercial industries, including sports. But the problems faced are not just with the capability to generate ideas, it is with their exploitation—the scaling up and out of innovations across the enterprise. It is this area where the success of sports innovation can provide useful lessons to military officers.

Moving Off the Field

Of course, these topics are not likely to draw the same level of passion as the annual Army-Navy game. That’s because the on-field competition is where the rubber meets the road. Nothing else about sports can compare to the “thrill of victory and the agony of defeat.”

There is a lesson for budding senior leaders, however. When an athlete’s playing career ends, some will move to management positions as general manager or other team or league position. Their perspective must move from the on-the-field product to off-the-field, where the focus is on preparation. It is the same with War College students, many of whom will spend much of their remaining time in the service managing the preparedness of the force and far less often leading troops into battle. This different perspective requires a change of mindset about decision making, leadership, engagement, and competition. For some, this environment is foreign. Yet familiarity with sports—both the on- and off-field environments, can provide insights that smooth the transition and allow for novel ways of exploring complex strategic issues. Doing so is easier if one chooses the right metaphors and analogies.

Tom Galvin is Associate Professor of Resource Management in the Department of Command Leadership and Management (DCLM) as well as the leadership and management instructor for the Carlisle Scholars Program at the United States Army War College. He is the author of the monograph Leading Change in Military Organizations and companion Experiential Activity Book.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

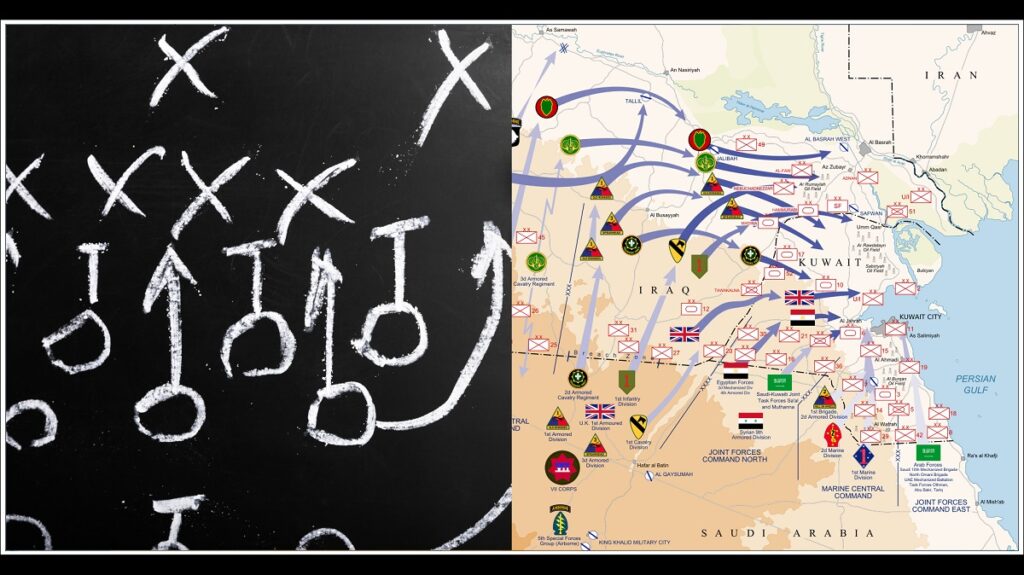

Photo Description: Map of ground operations of Operation DESERT STORM starting invasion February 24-28th 1991. Shows allied and Iraqi forces. Special arrows indicate the American 101st Airborne division moved by air and where the French 6st light division and American 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment provided security.

Photo Credit: Left – Image by fabrikasimf on Freepik; Right – U.S. DoD vector created byJeff Dahl via Wikimedia Commons