Managing homeland security challenges requires practitioners to engage in a discursive space that regularly increases in complexity and scope.

For this Whiteboard we reached out to several skilled practitioners in collaboration with the Homeland Security Experts Group (HSEG) with the following prompt:

What do you envision as the greatest challenges facing homeland security and domestic intelligence for the next decade?

With a mission to elevate and invigorate the conversations around homeland security risks and bring ground truth to the discussion, the HSEG is an independent, nonpartisan group of homeland security policy and counter-terrorism experts who convene periodically to discuss issues in depth, share information and ideas with the Secretary of Homeland Security and other policymakers, increase awareness of the evolving risks facing our nation, and help make our country safer. The Homeland Security Experts Group is co-chaired by former Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff and former Congresswoman Jane Harman. HSEG, while independent in its operations and pursuits, is supported by The MITRE Corporation. All of this was made possible through the coordination efforts of the U.S. Army War College De Serio Chair of Strategic Intelligence, Dr. Genevieve Lester.

Readers are invited to make their own contributions in the comments section.

1. Patricia F.S. Cogswell, Strategic Advisor, National Security Sector

Over the last 30 years, we have seen an increase in the number and types of threats and challenges affecting our country, our allies, and those who share our interests. At the same time, we have seen a series of activities that have diminished our public institutions and hindered the abilities of public servants to prevent, protect, and respond to these threats.

This includes highly visible actions, such as the politicization of department and agency missions; the failure of leaders and organizations to hold those who abuse the public trust accountable; and agencies who have failed to build a culture of respect and compassion internally or with the public. It also includes less visible, but systemic issues, such as the difficulty in attracting and retaining new talent, with the needed diversity of viewpoint and background to respond in our complex environment. The damage from these activities has been exponentially increased in our current environment, where meaningful public policy discussions are often drowned out by dueling “quick hit” press and social media reporting, or, even more concerning, disinformation campaigns funded and managed by foreign nations and other groups seeking to promote distrust or actual violence.

The consequence of these activities are institutions that are less prepared, less capable to carry out their mission and respond to emerging threats. It has also meant that institutions are less likely to work across organizational lines to share needed information, because of a lack of trust within and between organizations and cultures.

We must reverse this trend. We must consciously choose to reinvest in our institutions and the public servants we rely on to counter these threats. We must find new ways to have meaningful, open conversations about what domestic intelligence should be collected, and how it should be used by domestic law enforcement. These changes mean we have to increase our efforts to counter the cyber threats we face – both disinformation campaigns and cyber theft of intellectual property and information. We must increase Department and Agency transparency, establishing and using standardized mechanisms to provide the American public with reliable, fact-based information in order to promote a healthy public policy discussion about their missions and actions they take. We must depoliticize our public institutions. Our public institutions, from military to law enforcement, to intelligence, to diplomacy, to homeland security, are charged with implementing the policy direction of elected and appointed officials. But they shouldn’t be used or viewed as political tools. Finally, and most importantly, we must seek to reestablish confidence in those who chose to be public servants and ignite a passion in the next generation to commit to public service.

2. Jonathan Miller, Crime Analyst, Portland Police Bureau, Portland, Oregon

To what does the United States of the 21st century owe its power? Is it its military might, or inventive policy? Is it its economic prowess, or perhaps its dexterity in the face of unique and grand challenges? No, it is none of these. Rather, it is knowledge, or more acutely it is the capacity to marshal vast quantities of information so as to assure the continued security of those values we as Americans hold most dear: Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

The development of advanced communication technologies, alongside truly incredible computational capability, has allowed the homeland security enterprise (HSE) to identify, interdict, and mitigate homeland security threats like never before. However, such tools are not held solely in the hands of a single state. Both states and non-state actors alike may now reach a wide audience, irrespective of geographic distance, due to the degree to which our digital selves have been bound together by the internet. Should a malign actor desire to step into the global arena and undermine faith in institutions, propagate twisted ideologies, or render an adversary more divided and vulnerable, the cost of admission has never been so low. Why waste a bomb when a tweet will do?

Managing homeland security challenges requires practitioners to engage in a discursive space that regularly increases in complexity and scope. From an intelligence-gathering perspective this means doing the impossible: identifying reliable sources simultaneously with their genesis, and doing so with a collection of sources that appear to have all the promiscuous restraint of a swarm of fruit flies. Further, each new iteration has distinguished itself by presenting novel communication methods, thereby complicating intelligence gathering and requiring the establishment of ethical guidelines and standards for engaging in literally new spaces. Failing to do so will undermine public perception of the legitimacy of both actions and outcomes. This intersection will be a principle challenge for the foreseeable future: navigating an impossible space, while abiding by yet-to-be-written guidelines and being held to an unarticulated standard.

And as always, one last wrinkle. Gathering the best information cannot be possible if resources are not directed toward the smaller components of the HSE. For example, the NYPD has a relatively robust intelligence capability, but what about more rural environments? I somehow doubt a terrorist training camp is more likely to pop up in Central Park than in rural Oregon, yet the likelihood that agencies operating in rural jurisdictions actually have the resources to see-something-say-something is low. Consider for a moment how many officers, how many potential sensors there are in the United States that have yet to have been leveraged. What a waste. There can be no information sharing absent partnerships, and there can be no partnerships absent the political will to create them. The challenges faced by the HSE and the American public will only continue to grow in scope and complexity. Generating the will to empower more of us to contribute will be critical moving forward.

3. John Pistole, Former Transportation Security Administration administrator and Deputy Director, FBI

There are the obvious challenges in the realm of Cyber Security, whether threats to critical infrastructure from foreign actors, both State-sponsored and otherwise, or theft of private sector intellectual property. Add to those major challenges, the day-to-day ransomware attacks on small businesses, municipal governments and individuals are pervasive and growing. Identity theft, denial of service attacks, malware and phishing schemes continue to proliferate, perhaps especially so during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic where individuals and businesses have migrated online for much of their daily lives and transactions.

One key series of questions is what role the U.S. Government, particularly DHS, plays in:

1) Identifying cyber risks and vulnerabilities—and then deciding whom to share that information with;

2) Taking proactive steps to help the private sector prevent or mitigate the damage of cyber attacks; and

3) Determining what public-private partnerships will best serve the American people in mitigating cyber threats over the next decade?

Another challenge apart from cyber threats is the global rise of anti-government domestic groups and individuals who may take violent actions if their preferred leader is not elected or re-elected. DHS has worked closely with the FBI in identifying these groups and conducting investigations where warranted. This challenge needs to be watched closely here in the U.S. given the current tension in U.S. politics and race relations. Perhaps a Blue-Ribbon Panel should be convened to address these issues.

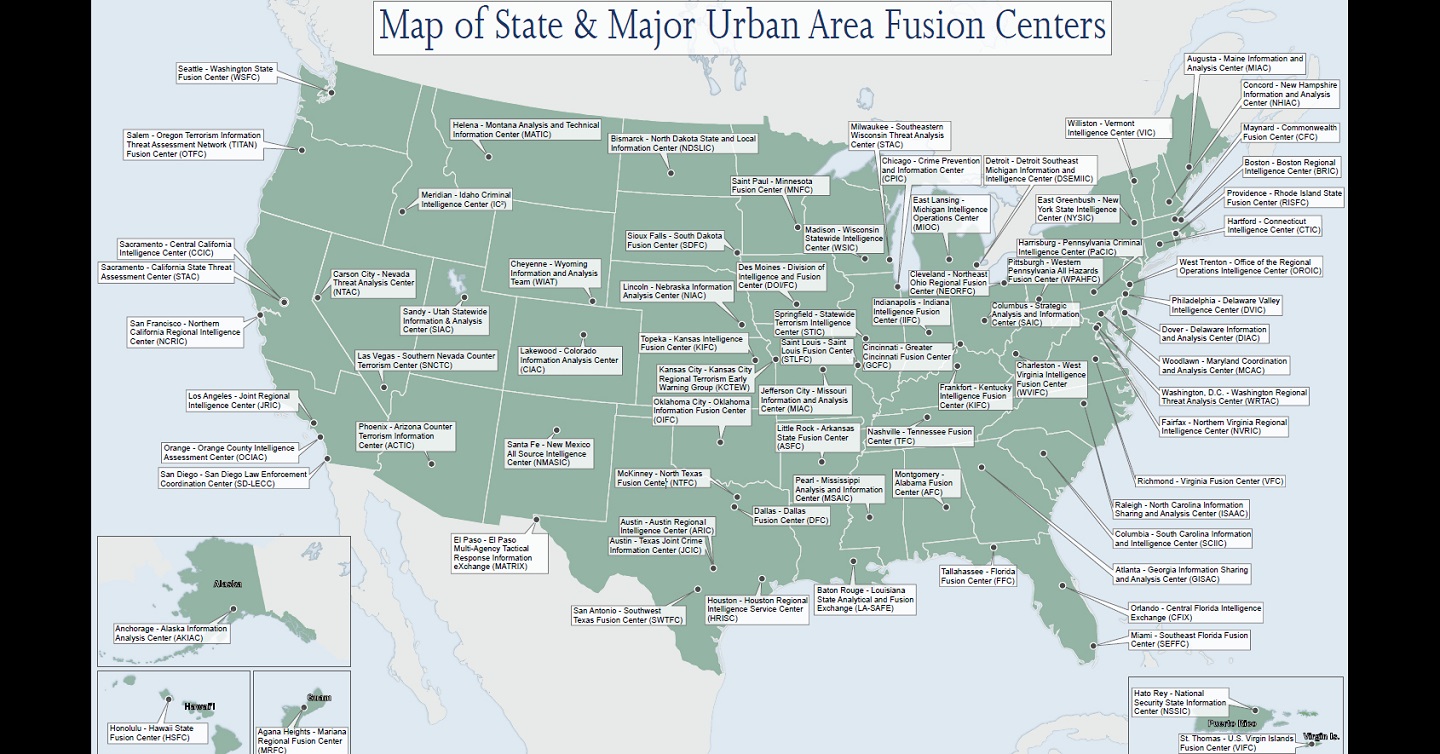

The goal for all law enforcement and intelligence community departments and agencies is to share relevant information on a timely basis, usually to prevent a terrorist or other attack. State and local fusion centers proliferated after DHS was created in 2003 to help collect, analyze and share counterterrorism information/intelligence. Some have done exceptionally well, some not so much. So, one challenge for the next decade is to reassess the roles and responsibilities of these fusion centers and for DHS and the FBI to determine their usefulness and viability moving forward.

The other key to successful prevention of attacks is information sharing at and among federal agencies, particularly between DHS, FBI and the other 15 agencies within the USIC. Much has been written about the lack of sharing between the CIA and FBI prior to 9/11, including by the 9/11 Commission (could the attack have been prevented?), and all the initiatives since then to address the gaps. The creation of the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) and the Office of Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) were both major improvements to that of the pre-9/11 world, but a fresh examination of the efficacy of current and prospective sharing of intelligence and information is warranted as we near the 20-year anniversary of 9/11.

4. Dr. John P. Sullivan is a retired Los Angeles Sheriff’s lieutenant, instructor at the Safe Communities Institute, University of Southern California, and Senior Fellow at Small Wars Journal-El Centro.

The domestic intelligence and information-sharing domain is facing deep challenges from the convergence of threats. These threats range from global societal instability due to the rise of new technologies such as artificial intelligence and robotics with the potential to rock socioeconomic foundations and fuel tensions between states and non-state actors. Add to this the risks associated with climate change—including the denial of climate risks, as well as climate-induced migration and conflict. The rise of identity politics is simultaneously splintering states and giving rise to globally connected non-state actors such as right wing extremists and transnational criminal organizations. Here the distinction between ‘domestic’ and ‘international’ security is blurring in favor of a distributed ‘global’ security framework—or rather a global-local (‘glocal’) security framework.

While there is a technological component to these threats and the ability to negotiate them, the primary challenge is not technological. The primary challenge is cognitive. How do we understand the dark webs of deception including the use of ‘deep fakes’ and extreme propaganda as both nation-states and non-state adversaries wage political, social, and cultural information (and influence) operations against the United States at federal and state levels? This narrative space where memes, branding, and information and disinformation forge new political and cultural allegiances is the new battleground for domestic tranquility and stability.

These new informational conflicts embrace both hard and soft power and involve complex networks of state and non-state actors operating across physical boundaries and within and through cyberspace. Foreign intelligence officers, domestic extremists, corrupt and co-opted government officials—including police can manipulate reality and stimulate false narratives that erode democratic processes and the rule of law. Negotiating this complexity and getting real, validated ground truth is an intelligence problem centered on effective analysis (or analysis-synthesis) and trust at local, state, federal, international, and corporate levels to protect the global commons.

Information surety—that is, trust and confidence in both core data and analytical partners—is essential if all the security services and political decision-makers (federal, state and local/metropolitan) are going to protect the populace, manage disorder, and preserve liberties. This requires a firm grounding in ethics and Constitutional norms. Human rights law and state and local statutes must join national security law to forge the new networked, civil-military, national-civil society capabilities needed to understand and ultimately shape these challenges. This ethical framework must avoid the politicization of intelligence and blunt the ‘maskirovka’ (deception, denial, and disinformation) of foreign interference in domestic politics.

The global order and state polities are potentially splintering as a new order emerges where both hostile state competitors and criminal adversaries seek to gain power and advantage. These ‘power-counterpower’ struggles will exist at all levels of governance and maneuver. This requires appreciation of networked realities and more than ‘information-sharing’ and building a federal-national domestic-foreign intelligence network that sustains liberties, security, and the rule of law. Counterintelligence and multilateral mechanisms for distributed intelligence fusion integrating state and metropolitan capabilities are increasingly needed. Analytical tradecraft, network protocols (doctrine), and encouraging the ‘co-production’ of intelligence are essential ingredients for managing the spectrum of emerging threats.

5. Lieutenant General (Ret.) Guy C. Swan III, Former Commanding General, U.S. Army North (ARNORTH), Former Director of Operations, U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM)

The Challenge: Build a Culture of Preparedness

If the ill-fated year of 2020 taught us anything it’s that there is a high price to pay for being unprepared. The greatest challenge in the next decade for homeland security and domestic intelligence will be to build a culture of preparedness.

The novel coronavirus pandemic exposed just how unprepared our nation was at all levels of government for a bio threat. Combine that with the civil unrest that burst onto several American cities almost overnight, a series of hurricanes and wildfire occurrences across the country, and the ever-present threat of terrorism and you get a hard lesson on what happens when we take domestic preparedness for granted. All these calamities cry out for a new culture of preparedness in the United States.

Disaster and emergency can take many forms and emerge at anytime, anywhere and it seems that this trend will continue for the foreseeable future.

Planning, preparation, and practice – informed by smart information and intelligence sharing and communication with the public – will go a long way toward mitigating, if not preventing, such catastrophes in the future.

Over the past 30 years we’ve seen attention on preparedness ebb and flow. The Ready.gov campaign once had momentum but lost it. Likewise, the “See Something, Say Something” drive seems to have faded. We must do better at finding ways for local, state, federal, territorial, tribal, and even family-level structures to regain a level common sense of readiness without creating unnecessary alarmism.

Clearly, we’ll never be fully prepared for every eventuality. But being prepared for the 80% of threats we know will occur frees up resources, attention, and energy to apply to the unexpected “black swan” events that will inevitably surprise us. This way we can better absorb the shock of unknown and unpredictable emergencies. This is standard practice in countries like Israel and the U.K. where resilience is the goal, not 100% prevention. We can do it here, too.

How can we build a similar culture of preparedness and resiliency in the U.S.?

1) It starts in hometown America by encouraging the traditional American concepts of self-sufficiency and self-reliance. Families, neighbors, and communities have always recognized their obligation to one another’s safety and well-being. We can build on that.

2) At the governmental level, let’s reinvigorate the National Exercise Program with realistic scenarios that stress elected officials, first responders, and indeed citizens themselves.

3) Our domestic intelligence and information sharing enterprise needs to be broadened to move beyond counterterrorism toward an all-hazards approach. Everyday emphasis on a phrase often used in the military – “Who else needs to know this?” – is much needed.

4) We should demand that our elected officials participate in exercises and training, so they don’t have to experience a crisis for the first time during an actual event. Sadly, we saw this all too frequently in 2020.

5) Continue to train, trust, and resource a cadre of emergency management professionals at each level of government to be our eyes, ears, and early warning of impending danger.

6) Strengthen mutual aid agreements between and among local and state jurisdictions given that no single agency or department will ever have all the tools needed in a crisis.

And finally, enable resiliency wherever and whenever possible. Vigilant information gathering and sharing, prior planning, and quick response will soften the blow of a catastrophic event and speed recovery and a return to a sense normalcy.

6. Bert Tussing, Center for Strategic Leadership, US Army War College

The greatest challenge to homeland security lies in the delicate divide described by the former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff as Competition and Conflict.

Viewed from the perspective of real or potential adversaries, “competition” implies gaining positions of advantage—diplomatic, informational, economic, or otherwise. As the degree of this advantage jeopardizes the interests of the United States and the well-being of its citizens, the threat to those citizens may be envisioned as progressing along a scale beginning at competition, continuing through coercion, on the way to conflict.

“On the way”… but not necessarily discernibly so to all observers. Particularly viewed against the background of traditional conflict, wherein recognizable trip wires or redlines have signaled open aggression to both antagonists and defenders, the new brand of hostility may be masked. In what has been variously referred to as gray zone activities, hybrid threats and the like, our enemies may advance to the brink of marked hostilities, and hold.

Evidence of this new brinkmanship is everywhere, especially in the cyber regime. Government websites are constantly under assault by hackers whose origins are exceedingly difficult to pinpoint. Similar attacks, often characterized as probing, are taking place across every sector of critical infrastructure, in both public and private domains. Criminal elements are certainly involved in these intrusions, but the more ominous concerns emanate from nation state threats, including hits levied against us by proxies. If held analogous to the physical domain, many of these incursions could be interpreted as intelligence preparation of the battlefield, allowing the adversary to not only discover vulnerabilities, but to potentially develop vulnerabilities across national critical functions.

The danger, then, lies in the veiled incursions, exacerbated by a lack of means to clearly attribute the attacks to a particular foe or set of foes. But when attribution is clear, the question of appropriate response still seems unanswered. What actions, for instance, should be weighed against activities that have not done damage to infrastructure, but could be reasonably expected to do so if maintained or increased? What are the redlines for an imminent threat in this new security environment? What sorts of engagements or trends would justify a preemptive action on the part of the United States, viewed on the world stage?

I would suggest that branches off of these concerns could easily be drawn to questions surrounding domestic intelligence and information sharing. Both topics will have to be addressed to any new strategies to meet this new and evolving security dilemma. In all three cases, the country’s leadership will have to balance concerns over security with the “inalienable” rights of our people…indeed, all people legitimately within our borders. But our fervent desires to maintain the ethic which defines our nation must be viewed against the malicious intent of actors who would deliberately use those concerns against us. A new, clearer vision of how to frame this 21st century threat to our society must be developed; one that provides a foundation for clear deterrence through devastating response.

The views expressed in this Whiteboard Exercise are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

Photo Description: State and Major Urban Area Fusion Centers across the United States

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the Maine Information and Analysis Center

Other releases in the “Whiteboard” series:

- THE ADMINISTRATION’S TOP FOREIGN POLICY PRIORITY (A WHITEBOARD)

- IMAGINING OVERMATCH: CRITICAL DOMAINS IN THE NEXT WAR (A WHITEBOARD)

- THAT ONE MOST IMPORTANT THING: (A WHITEBOARD)

- SHALL WE PLAY A GAME?

(WARGAMING ROOM) - WAR(GAMING) WHAT IS IT GOOD FOR? (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION REVISITED: (A WHITEBOARD)

- WHAT GOOD IS GRAND STRATEGY? (A WHITEBOARD)

- THE UNITED NATIONS’ GREATEST ACCOMPLISHMENT: (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION: (A WHITEBOARD)

- THE MOST IMPORTANT LEGACY OF THE VIETNAM CONFLICT: (A WHITEBOARD)