Managing homeland security challenges requires practitioners to engage in a discursive space that regularly increases in complexity and scope.

For this Whiteboard we reached out to several skilled practitioners in collaboration with the Homeland Security Experts Group (HSEG) with the following prompt:

What do you envision as the greatest challenges facing homeland security and domestic intelligence for the next decade?

With a mission to elevate and invigorate the conversations around homeland security risks and bring ground truth to the discussion, the HSEG is an independent, nonpartisan group of homeland security policy and counter-terrorism experts who convene periodically to discuss issues in depth, share information and ideas with the Secretary of Homeland Security and other policymakers, increase awareness of the evolving risks facing our nation, and help make our country safer. The Homeland Security Experts Group is co-chaired by former Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff and former Congresswoman Jane Harman. HSEG, while independent in its operations and pursuits, is supported by The MITRE Corporation. All of this was made possible through the coordination efforts of the U.S. Army War College De Serio Chair of Strategic Intelligence, Dr. Genevieve Lester.

Readers are invited to make their own contributions in the comments section.

1. Patricia F.S. Cogswell, Strategic Advisor, National Security Sector

Over the last 30 years, we have seen an increase in the number and types of threats and challenges affecting our country, our allies, and those who share our interests. At the same time, we have seen a series of activities that have diminished our public institutions and hindered the abilities of public servants to prevent, protect, and respond to these threats.

This includes highly visible actions, such as the politicization of department and agency missions; the failure of leaders and organizations to hold those who abuse the public trust accountable; and agencies who have failed to build a culture of respect and compassion internally or with the public. It also includes less visible, but systemic issues, such as the difficulty in attracting and retaining new talent, with the needed diversity of viewpoint and background to respond in our complex environment. The damage from these activities has been exponentially increased in our current environment, where meaningful public policy discussions are often drowned out by dueling “quick hit” press and social media reporting, or, even more concerning, disinformation campaigns funded and managed by foreign nations and other groups seeking to promote distrust or actual violence.

The consequence of these activities are institutions that are less prepared, less capable to carry out their mission and respond to emerging threats. It has also meant that institutions are less likely to work across organizational lines to share needed information, because of a lack of trust within and between organizations and cultures.

We must reverse this trend. We must consciously choose to reinvest in our institutions and the public servants we rely on to counter these threats. We must find new ways to have meaningful, open conversations about what domestic intelligence should be collected, and how it should be used by domestic law enforcement. These changes mean we have to increase our efforts to counter the cyber threats we face – both disinformation campaigns and cyber theft of intellectual property and information. We must increase Department and Agency transparency, establishing and using standardized mechanisms to provide the American public with reliable, fact-based information in order to promote a healthy public policy discussion about their missions and actions they take. We must depoliticize our public institutions. Our public institutions, from military to law enforcement, to intelligence, to diplomacy, to homeland security, are charged with implementing the policy direction of elected and appointed officials. But they shouldn’t be used or viewed as political tools. Finally, and most importantly, we must seek to reestablish confidence in those who chose to be public servants and ignite a passion in the next generation to commit to public service.

2. Jonathan Miller, Crime Analyst, Portland Police Bureau, Portland, Oregon

To what does the United States of the 21st century owe its power? Is it its military might, or inventive policy? Is it its economic prowess, or perhaps its dexterity in the face of unique and grand challenges? No, it is none of these. Rather, it is knowledge, or more acutely it is the capacity to marshal vast quantities of information so as to assure the continued security of those values we as Americans hold most dear: Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

The development of advanced communication technologies, alongside truly incredible computational capability, has allowed the homeland security enterprise (HSE) to identify, interdict, and mitigate homeland security threats like never before. However, such tools are not held solely in the hands of a single state. Both states and non-state actors alike may now reach a wide audience, irrespective of geographic distance, due to the degree to which our digital selves have been bound together by the internet. Should a malign actor desire to step into the global arena and undermine faith in institutions, propagate twisted ideologies, or render an adversary more divided and vulnerable, the cost of admission has never been so low. Why waste a bomb when a tweet will do?

Managing homeland security challenges requires practitioners to engage in a discursive space that regularly increases in complexity and scope. From an intelligence-gathering perspective this means doing the impossible: identifying reliable sources simultaneously with their genesis, and doing so with a collection of sources that appear to have all the promiscuous restraint of a swarm of fruit flies. Further, each new iteration has distinguished itself by presenting novel communication methods, thereby complicating intelligence gathering and requiring the establishment of ethical guidelines and standards for engaging in literally new spaces. Failing to do so will undermine public perception of the legitimacy of both actions and outcomes. This intersection will be a principle challenge for the foreseeable future: navigating an impossible space, while abiding by yet-to-be-written guidelines and being held to an unarticulated standard.

And as always, one last wrinkle. Gathering the best information cannot be possible if resources are not directed toward the smaller components of the HSE. For example, the NYPD has a relatively robust intelligence capability, but what about more rural environments? I somehow doubt a terrorist training camp is more likely to pop up in Central Park than in rural Oregon, yet the likelihood that agencies operating in rural jurisdictions actually have the resources to see-something-say-something is low. Consider for a moment how many officers, how many potential sensors there are in the United States that have yet to have been leveraged. What a waste. There can be no information sharing absent partnerships, and there can be no partnerships absent the political will to create them. The challenges faced by the HSE and the American public will only continue to grow in scope and complexity. Generating the will to empower more of us to contribute will be critical moving forward.

3. John Pistole, Former Transportation Security Administration administrator and Deputy Director, FBI

There are the obvious challenges in the realm of Cyber Security, whether threats to critical infrastructure from foreign actors, both State-sponsored and otherwise, or theft of private sector intellectual property. Add to those major challenges, the day-to-day ransomware attacks on small businesses, municipal governments and individuals are pervasive and growing. Identity theft, denial of service attacks, malware and phishing schemes continue to proliferate, perhaps especially so during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic where individuals and businesses have migrated online for much of their daily lives and transactions.

One key series of questions is what role the U.S. Government, particularly DHS, plays in:

1) Identifying cyber risks and vulnerabilities—and then deciding whom to share that information with;

2) Taking proactive steps to help the private sector prevent or mitigate the damage of cyber attacks; and

3) Determining what public-private partnerships will best serve the American people in mitigating cyber threats over the next decade?

Another challenge apart from cyber threats is the global rise of anti-government domestic groups and individuals who may take violent actions if their preferred leader is not elected or re-elected. DHS has worked closely with the FBI in identifying these groups and conducting investigations where warranted. This challenge needs to be watched closely here in the U.S. given the current tension in U.S. politics and race relations. Perhaps a Blue-Ribbon Panel should be convened to address these issues.

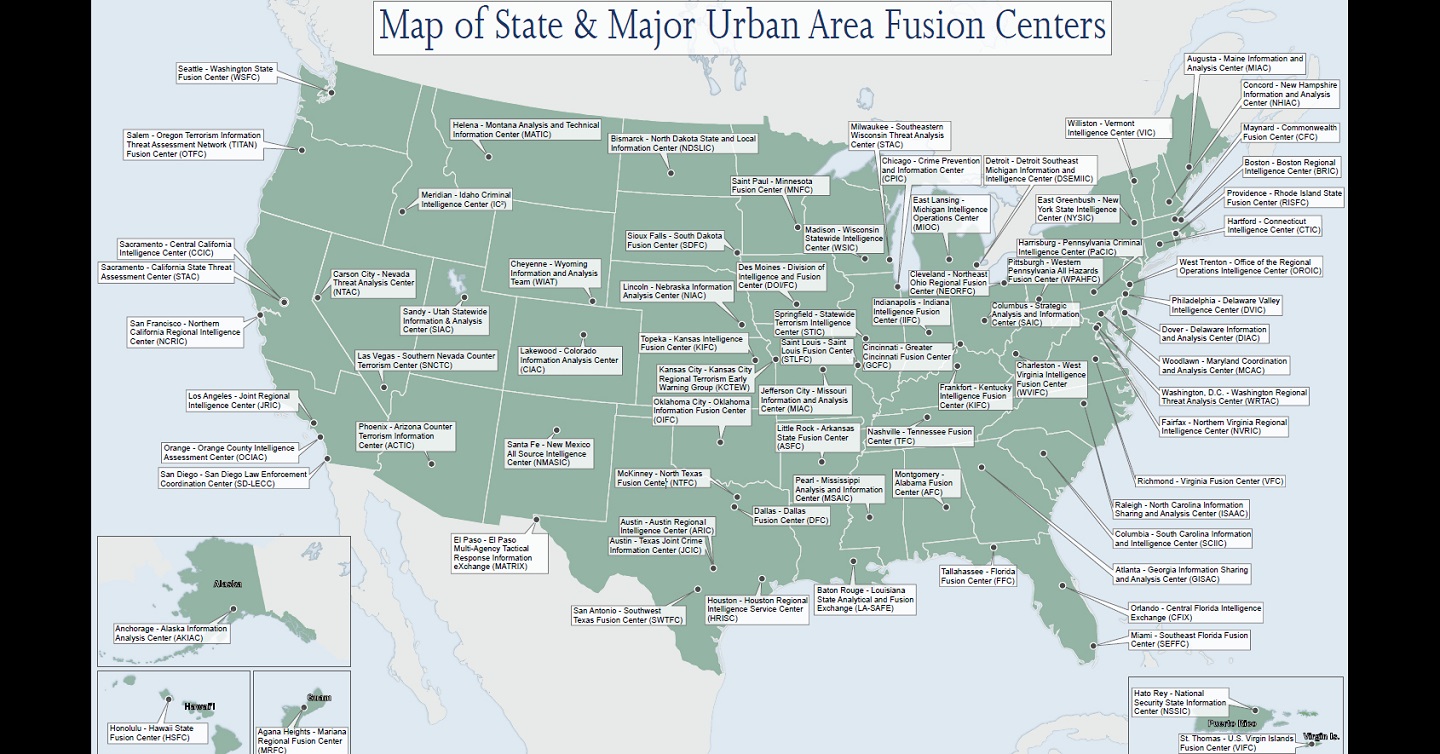

The goal for all law enforcement and intelligence community departments and agencies is to share relevant information on a timely basis, usually to prevent a terrorist or other attack. State and local fusion centers proliferated after DHS was created in 2003 to help collect, analyze and share counterterrorism information/intelligence. Some have done exceptionally well, some not so much. So, one challenge for the next decade is to reassess the roles and responsibilities of these fusion centers and for DHS and the FBI to determine their usefulness and viability moving forward.

The other key to successful prevention of attacks is information sharing at and among federal agencies, particularly between DHS, FBI and the other 15 agencies within the USIC. Much has been written about the lack of sharing between the CIA and FBI prior to 9/11, including by the 9/11 Commission (could the attack have been prevented?), and all the initiatives since then to address the gaps. The creation of the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) and the Office of Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) were both major improvements to that of the pre-9/11 world, but a fresh examination of the efficacy of current and prospective sharing of intelligence and information is warranted as we near the 20-year anniversary of 9/11.

4. Dr. John P. Sullivan is a retired Los Angeles Sheriff’s lieutenant, instructor at the Safe Communities Institute, University of Southern California, and Senior Fellow at Small Wars Journal-El Centro.

The domestic intelligence and information-sharing domain is facing deep challenges from the convergence of threats. These threats range from global societal instability due to the rise of new technologies such as artificial intelligence and robotics with the potential to rock socioeconomic foundations and fuel tensions between states and non-state actors. Add to this the risks associated with climate change—including the denial of climate risks, as well as climate-induced migration and conflict. The rise of identity politics is simultaneously splintering states and giving rise to globally connected non-state actors such as right wing extremists and transnational criminal organizations. Here the distinction between ‘domestic’ and ‘international’ security is blurring in favor of a distributed ‘global’ security framework—or rather a global-local (‘glocal’) security framework.

While there is a technological component to these threats and the ability to negotiate them, the primary challenge is not technological. The primary challenge is cognitive. How do we understand the dark webs of deception including the use of ‘deep fakes’ and extreme propaganda as both nation-states and non-state adversaries wage political, social, and cultural information (and influence) operations against the United States at federal and state levels? This narrative space where memes, branding, and information and disinformation forge new political and cultural allegiances is the new battleground for domestic tranquility and stability.

These new informational conflicts embrace both hard and soft power and involve complex networks of state and non-state actors operating across physical boundaries and within and through cyberspace. Foreign intelligence officers, domestic extremists, corrupt and co-opted government officials—including police can manipulate reality and stimulate false narratives that erode democratic processes and the rule of law. Negotiating this complexity and getting real, validated ground truth is an intelligence problem centered on effective analysis (or analysis-synthesis) and trust at local, state, federal, international, and corporate levels to protect the global commons.

Information surety—that is, trust and confidence in both core data and analytical partners—is essential if all the security services and political decision-makers (federal, state and local/metropolitan) are going to protect the populace, manage disorder, and preserve liberties. This requires a firm grounding in ethics and Constitutional norms. Human rights law and state and local statutes must join national security law to forge the new networked, civil-military, national-civil society capabilities needed to understand and ultimately shape these challenges. This ethical framework must avoid the politicization of intelligence and blunt the ‘maskirovka’ (deception, denial, and disinformation) of foreign interference in domestic politics.

The global order and state polities are potentially splintering as a new order emerges where both hostile state competitors and criminal adversaries seek to gain power and advantage. These ‘power-counterpower’ struggles will exist at all levels of governance and maneuver. This requires appreciation of networked realities and more than ‘information-sharing’ and building a federal-national domestic-foreign intelligence network that sustains liberties, security, and the rule of law. Counterintelligence and multilateral mechanisms for distributed intelligence fusion integrating state and metropolitan capabilities are increasingly needed. Analytical tradecraft, network protocols (doctrine), and encouraging the ‘co-production’ of intelligence are essential ingredients for managing the spectrum of emerging threats.

5. Lieutenant General (Ret.) Guy C. Swan III, Former Commanding General, U.S. Army North (ARNORTH), Former Director of Operations, U.S. Northern Command (NORTHCOM)

The Challenge: Build a Culture of Preparedness

If the ill-fated year of 2020 taught us anything it’s that there is a high price to pay for being unprepared. The greatest challenge in the next decade for homeland security and domestic intelligence will be to build a culture of preparedness.

The novel coronavirus pandemic exposed just how unprepared our nation was at all levels of government for a bio threat. Combine that with the civil unrest that burst onto several American cities almost overnight, a series of hurricanes and wildfire occurrences across the country, and the ever-present threat of terrorism and you get a hard lesson on what happens when we take domestic preparedness for granted. All these calamities cry out for a new culture of preparedness in the United States.

Disaster and emergency can take many forms and emerge at anytime, anywhere and it seems that this trend will continue for the foreseeable future.

Planning, preparation, and practice – informed by smart information and intelligence sharing and communication with the public – will go a long way toward mitigating, if not preventing, such catastrophes in the future.

Over the past 30 years we’ve seen attention on preparedness ebb and flow. The Ready.gov campaign once had momentum but lost it. Likewise, the “See Something, Say Something” drive seems to have faded. We must do better at finding ways for local, state, federal, territorial, tribal, and even family-level structures to regain a level common sense of readiness without creating unnecessary alarmism.

Clearly, we’ll never be fully prepared for every eventuality. But being prepared for the 80% of threats we know will occur frees up resources, attention, and energy to apply to the unexpected “black swan” events that will inevitably surprise us. This way we can better absorb the shock of unknown and unpredictable emergencies. This is standard practice in countries like Israel and the U.K. where resilience is the goal, not 100% prevention. We can do it here, too.

How can we build a similar culture of preparedness and resiliency in the U.S.?

1) It starts in hometown America by encouraging the traditional American concepts of self-sufficiency and self-reliance. Families, neighbors, and communities have always recognized their obligation to one another’s safety and well-being. We can build on that.

2) At the governmental level, let’s reinvigorate the National Exercise Program with realistic scenarios that stress elected officials, first responders, and indeed citizens themselves.

3) Our domestic intelligence and information sharing enterprise needs to be broadened to move beyond counterterrorism toward an all-hazards approach. Everyday emphasis on a phrase often used in the military – “Who else needs to know this?” – is much needed.

4) We should demand that our elected officials participate in exercises and training, so they don’t have to experience a crisis for the first time during an actual event. Sadly, we saw this all too frequently in 2020.

5) Continue to train, trust, and resource a cadre of emergency management professionals at each level of government to be our eyes, ears, and early warning of impending danger.

6) Strengthen mutual aid agreements between and among local and state jurisdictions given that no single agency or department will ever have all the tools needed in a crisis.

And finally, enable resiliency wherever and whenever possible. Vigilant information gathering and sharing, prior planning, and quick response will soften the blow of a catastrophic event and speed recovery and a return to a sense normalcy.

6. Bert Tussing, Center for Strategic Leadership, US Army War College

The greatest challenge to homeland security lies in the delicate divide described by the former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff as Competition and Conflict.

Viewed from the perspective of real or potential adversaries, “competition” implies gaining positions of advantage—diplomatic, informational, economic, or otherwise. As the degree of this advantage jeopardizes the interests of the United States and the well-being of its citizens, the threat to those citizens may be envisioned as progressing along a scale beginning at competition, continuing through coercion, on the way to conflict.

“On the way”… but not necessarily discernibly so to all observers. Particularly viewed against the background of traditional conflict, wherein recognizable trip wires or redlines have signaled open aggression to both antagonists and defenders, the new brand of hostility may be masked. In what has been variously referred to as gray zone activities, hybrid threats and the like, our enemies may advance to the brink of marked hostilities, and hold.

Evidence of this new brinkmanship is everywhere, especially in the cyber regime. Government websites are constantly under assault by hackers whose origins are exceedingly difficult to pinpoint. Similar attacks, often characterized as probing, are taking place across every sector of critical infrastructure, in both public and private domains. Criminal elements are certainly involved in these intrusions, but the more ominous concerns emanate from nation state threats, including hits levied against us by proxies. If held analogous to the physical domain, many of these incursions could be interpreted as intelligence preparation of the battlefield, allowing the adversary to not only discover vulnerabilities, but to potentially develop vulnerabilities across national critical functions.

The danger, then, lies in the veiled incursions, exacerbated by a lack of means to clearly attribute the attacks to a particular foe or set of foes. But when attribution is clear, the question of appropriate response still seems unanswered. What actions, for instance, should be weighed against activities that have not done damage to infrastructure, but could be reasonably expected to do so if maintained or increased? What are the redlines for an imminent threat in this new security environment? What sorts of engagements or trends would justify a preemptive action on the part of the United States, viewed on the world stage?

I would suggest that branches off of these concerns could easily be drawn to questions surrounding domestic intelligence and information sharing. Both topics will have to be addressed to any new strategies to meet this new and evolving security dilemma. In all three cases, the country’s leadership will have to balance concerns over security with the “inalienable” rights of our people…indeed, all people legitimately within our borders. But our fervent desires to maintain the ethic which defines our nation must be viewed against the malicious intent of actors who would deliberately use those concerns against us. A new, clearer vision of how to frame this 21st century threat to our society must be developed; one that provides a foundation for clear deterrence through devastating response.

The views expressed in this Whiteboard Exercise are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

Photo Description: State and Major Urban Area Fusion Centers across the United States

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the Maine Information and Analysis Center

Other releases in the “Whiteboard” series:

- THE ADMINISTRATION’S TOP FOREIGN POLICY PRIORITY (A WHITEBOARD)

- IMAGINING OVERMATCH: CRITICAL DOMAINS IN THE NEXT WAR (A WHITEBOARD)

- THAT ONE MOST IMPORTANT THING: (A WHITEBOARD)

- SHALL WE PLAY A GAME?

(WARGAMING ROOM) - WAR(GAMING) WHAT IS IT GOOD FOR? (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION REVISITED: (A WHITEBOARD)

- WHAT GOOD IS GRAND STRATEGY? (A WHITEBOARD)

- THE UNITED NATIONS’ GREATEST ACCOMPLISHMENT: (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION: (A WHITEBOARD)

- THE MOST IMPORTANT LEGACY OF THE VIETNAM CONFLICT: (A WHITEBOARD)

Underpinning our information gathering and intelligence development should be the understanding that “just because we can, doesn’t mean we should.” This is particularly relevant when gathering information and developing intelligence. Since the Wars on Drugs and Terror began, in our zeal to “protect,” some have found the 4th Amendment (and its spirit) a hurdle that needs to be creatively sidestepped.

We should not be collecting information on American citizens without clear legal and moral justification for doing so. Biometrics/other tools are “easy” (and create wealth for manufacturers and their purveyors) but their long-term impact is to damage the social fabric and make all Americans feel like criminals. You rarely solve a governance problem with a tool (our penchant for “train and equip” over long-term institution building risks making bad actors more efficiently bad). When Americans feel “watched” all the time, they will practice avoidance and quit sharing information, making all of us less safe (a phenomena being seen in the use of police body cameras).

Short term thinking: the end justifies the means when the means is what makes a government legitimate among its people. If our means is wrong, we may just be pushing our disaffected into the hands of our enemies.

As to the question: “What do you envision as the greatest challenge facing homeland security and domestic intelligence for the next decade?”

My answer to this question would be: The threat that governments — working to advance global capitalism, free trade, international investment, etc., throughout the world — pose to every nation’s (to include our own nation’s) (a) way of life, way of governance, values, etc., and (b) individuals and groups privileged and protected by same.

In this regard, consider:

First, the following from Robert Gilpin’s “The Challenge of Global Capitalism: The World Economy in the 21st Century” (see Page 3 of the “Introduction” chapter):

“Capitalism is the most successful wealth-creating system the world has every known; no system, as the distinguished economist Joseph Schumpeter pointed out, has benefited ‘the common people’ as much. Capitalism, he observed, creates wealth through advancing continuously to ever higher levels of productivity and technological sophistication; this process requires that the ‘old’ be destroyed before the ‘new’ can take over.

This ‘process of creative destruction,’ to use Schumpeter’s term, produces many winners but also many losers, at least in the short term, and poses a serious threat to traditional values, beliefs and institutions.”

Next, consider the following from Matthew Hoh’s U.S. State Department resignation letter (see the Washington Post article of this same name):

“If the history of Afghanistan is one great stage play, the United States is no more than a supporting actor, among several previously, in a tragedy that not only pits tribes, valleys, clans, villages and families against one another, but, from at least King Zahir Shah’s reign (Afghanistan’s first “modernizer?”), has violently and savagely pitted the urban, secular, educated and modern of Afghanistan against the rural, religious, illiterate and traditional.” (Item in parenthesis is mine.)

Bottom Line Thought — Based on the Above:

As we all know:

a. The last major divide noted by Matthew Hoh above (in this case, re: the Global South country of Afghanistan), to wit: the divide between “the urban, secular, educated and modern and “the rural, religious, illiterate and traditional”,

b. This exact such divide (or one very similar to it) has now become dangerously manifest in the Global North also, for example, in places such as Great Britain (see the Brexit) and the United States (see the election, and the almost re-election, of Donald Trump).

The common cause of these divides, I suggest, are our post-Cold War foreign and domestic policies; which have been aimed at advancing capitalism, free trade, international investment, etc., more throughout the world. (As one would expect of a capitalist country, who had eliminated the threat –both at home and abroad — that had been posed by communism?)

However, as Robert Gilpin notes above, this activity (capitalism now “unleashed”) “poses a serious threat to traditional values, beliefs and institutions.”

Accordingly, it is this such “serious threat,” I suggest — and the consequences of same — that one should “envision as the greatest challenge facing homeland security and domestic intelligence for the next decade.”

(Why? Because such can be so easily be exploited by both foreign, and indeed domestic, “bad actors.”)

Many different things were mentioned in this Whiteboard and here are a few more.

The left-wing terrorists, not mentioned, have demonstrated that they are organized, funded, and have a membership. Recent problems have brought these to public attention, but little seems to be done.

Perhaps, due to a lack of political support and resolve, police forces have and will suffer future manpower shortages.

Much like the Vietnam War at home, media manipulation (for money and/or ideology) has been exposed, but without any penalties.

China has become the preeminent international force that has made no effort to hide their efforts for decades. They have often taken the “slow” way to collect information – one piece at a time.

Personnel in this country-wide effort should take advantage of former intelligence-trained personnel who were in the military, especially HUMINT types. Many have been in the fight and have seen much of the “bad guys” in their different forms, unlike the senior officers.

The threat to our security will never go away – acting nice only makes it worse.

As to the question: What do you envision as the greatest challenges facing homeland security and domestic intelligence for the next decade?

My answer would be: A lack of understanding of the political objectives of both ourselves and our adversaries, a lack of understanding of the basic “nature” of same and of the strategy that “we” and “they” have adopted to achieve our such objectives, a lack of understanding of one’s “natural allies” and “natural enemies” in such a competition/conflict and, finally, a lack of understanding of the determining role that “the main battlefield is in the mind” thinking, thus, plays in these such scenarios.

Explanation Part I:

During the Old Cold War of Yesterday (1945 – 1989), when the Soviets/the communists political objective and strategy was “expansionist,” “revolutionary” and “transformative” in nature — to wit: designed to advance the communist way of life, way of governance, values, etc., both in their own countries and indeed throughout the world — the U.S./the West, at that time and so as to combat same, went into “containment” mode; this, so as to prevent as many of these unwanted expansions/revolutions/ transformations, as possible, from being realized/from taking place (and especially here at home, and in our sphere of power, influence and control).

In this scenario (“they” are the expansionist/revolutionary/transformative mode — we are in “containment” mode):

a. “Their” “natural allies” (and, thus, “our” “natural enemies”) were the more-liberal members of both our own, and the world’s, populations. These “liberal” folks, quite often, could be seen as being the more-urban, the more-educated, the more-secular and, generally, the more-“modern” members of various states, societies, ethnic groups, etc. This, while:

b. “Our” “natural allies” (and, thus, “their” “natural enemies”) were the more-conservative members of both our own, and the world’s, populations. These “conservative” folks, quite often, could be seen as being the more-rural, the less-educated, the more-religious and, generally, the more-“traditional” members of various states, societies, etc. (to include our own).

In the New Cold War of Today, however, the very opposite of this is true.

Explanation Part II:

In the New Cold War of Today (from 1990 to at least the election of Donald Trump), the political objective and strategy of the U.S./the West has been “expansionist,” “revolutionary” and “transformative” in nature — in this case — designed to advance democracy, capitalism, free trade and foreign investment more throughout the world. Many of our adversaries in this New Cold War of Today (ex: Russia) — to combat our such unwanted advances — went into “containment” mode themselves; this, so as to prevent as many of our unwanted expansions, revolutions, transformations, etc., as possible, from being realized/from taking place (and especially in their own counties and sphere, or former sphere, of power, influence and control).

In this scenario (“we” are the expansionist/revolutionary/transformative mode now — “they” are in “containment” mode now):

a. “Their” “natural allies” (and, thus, “our” “natural enemies”) have been the more-conservative members of both our own, and the world’s, populations. These “conservative” folks, again quite often, are the more-rural, the less-educated, the more-religious and, generally, the more-“traditional” members of various states, societies, etc. (to include our own). This while:

b. “Our” “natural allies” (and, thus, “their” “natural enemies”) have been the more-liberal members of both our own, and the world’s, populations. These “liberal” folks, again quite often, are known to be the more-urban, the more-educated, the more-secular and, generally, the more-“modern” members of various states, societies, ethnic groups, etc.

As evidence to support my such New Cold War of Today thesis, consider the following:

“In his annual appeal to the Federal Assembly in December 2013, Putin formulated this ‘independent path’ ideology by contrasting Russia’s ‘traditional values’ with the liberal values of the West. He said: ‘We know that there are more and more people in the world who support our position on defending traditional values that have made up the spiritual and moral foundation of civilization in every nation for thousands of years: the values of traditional families, real human life, including religious life, not just material existence but also spirituality, the values of humanism and global diversity.’ He proclaimed that Russia would defend and advance these traditional values in order to ‘prevent movement backward and downward, into chaotic darkness and a return to a primitive state.’

In Putin’s view, the fight over values is not far removed from geopolitical competition. ‘[Liberals] cannot simply dictate anything to anyone just like they have been attempting to do over the recent decades,’ he said in an interview with the Financial Times in 2019. ‘There is also the so-called liberal idea, which has outlived its purpose. Our Western partners have admitted that some elements of the liberal idea, such as multiculturalism, are no longer tenable,’ he added. …

As Putin passes his 20th year as Russia’s president, his domestic and foreign policy appears intended to contrast his country’s ‘independent path’ with the liberal and decadent regimes in the West. The invented battle of Western values versus Russia’s ‘traditional values’ is part of a Kremlin effort to justify its broader actions in the eyes of Russian citizens, placing them in the context of a global struggle in which Russia is the target of aggression. Ignoring and violating the provisions of international organizations to which it is a party thus becomes a demonstration of defending its conservative values from European liberalism. … ”

(See the Wilson Center publication “Kennan Cable No. 53” and, therein, the article “Russia’s Traditional Values and Domestic Violence,” by Olimpiada Usanova, dated 1 June 2020.)

Bottom Line Thought — Based on the Above:

If one understands and agrees with my explanations here — and considers same in light of the quoted item that I have provided above re: President Putin — then I think it takes very little imagination, indeed, to likewise see and understand:

a. Why the Russians (et. al?) see that “the main battle space is in the mind” in the New Cold War of Today (much as it was during the Old Cold War of Yesterday?) and why, accordingly,

b. We must see same as “presenting the greatest challenge facing homeland security and domestic intelligence for the next decade.”

In order to address the question: “What do you envision as the greatest challenges facing homeland security and domestic intelligence for the next decade?;”

In order to answer this question, let me start by asking a question of my own, this being: What do certain of our opponents here at home — and certain of our opponents overseas — have in common?

The answer to this question, I suggest, is that both our opponents here at home, and our opponents overseas, are opposed to the political, economic, social and/or value changes that many of today’s political, corporate, military and educational leaders believe are necessary; this, for one’s country to remain competitive in the age of globalization.

Explanation:

In this regard, let me first provide some information noting the trend of (a) U.S. officials embracing/supporting political, economic, social and/or value “change;” this, so as to (b) ensure that our country might remain competitive today and going forward:

“Even more telling than its use of elite opinion in ‘Lawrence’ was the Court’s unembarrassed reliance on elite views to determine the scope of a highly contested constitutional anti-discrimination norm in ‘Grutter.” Relying extensively on amicus briefs submitted by elite corporate, military, and educational authorities, Justice O’Conner, writing for the majority, asserted the following:

“Major American businesses have made clear that the skills needed in today’s increasingly global marketplace can only be developed through exposure to widely diverse people, cultures, ideas, and viewpoints. What is more, high-ranking retired officers and civilian leaders of the United States military assert that ‘[based on their] decades of experience,’ a ‘highly qualified, racially diverse officer corps … is essential to the military’s ability to fulfill its principle mission to provide national security.’ …”

“In short, the Court based its constitutional reasoning on the contention of a group of the Nation’s key corporate, political, and military leaders that the Nation’s prospects of success in the face of international strategic threats, as well as continued stability and perceived legitimacy in its domestic political institutions, required racial preferences in elite formation through our major educational institutions.”

(See the 2005 Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law paper entitled: “Moral Communities or a Market State: The Supreme Court’s Vision of the Police Power in the Age of Globalization,” by Antonio F. Perez and Robert J. Delahunty, Page 699)

From this perspective, one can easily see what these folks’ opponents — both here at home and there overseas — might have in common; this being, a “resistance to change”/a “containment of change” agenda — so as to retain the status quo. (Or, if too much unwanted change is thought to have already taken place, then a common agenda to return to a more-traditional, and thus a more-moral, status quo anti.) We know of the MAGA movement here in the U.S. in this regard. For a “foreign” example of this such phenomenon, consider the following:

“In his annual appeal to the Federal Assembly in December 2013, Putin formulated this ‘independent path’ ideology by contrasting Russia’s ‘traditional values’ with the liberal values of the West. He said: ‘We know that there are more and more people in the world who support our position on defending traditional values that have made up the spiritual and moral foundation of civilization in every nation for thousands of years: the values of traditional families, real human life, including religious life, not just material existence but also spirituality, the values of humanism and global diversity.’ He proclaimed that Russia would defend and advance these traditional values in order to ‘prevent movement backward and downward, into chaotic darkness and a return to a primitive state.’”

(See the Wilson Center publication “Kennan Cable No. 53” and, therein, the article “Russia’s Traditional Values and Domestic Violence,” by Olimpiada Usanova, dated 1 June 2020.)

Note Putin’s suggestion here that modern western civilization’s efforts toward further progress, somehow, equates to what looks like the Dark Ages. When, in truth, the Dark Ages were a time when a return to “traditional values” (such as Putin, et. al, advocate today) equated to “movement backward and downward,” etc.

Bottom Line Thought — Based on the Above:

In sum, then, to answer the question: “What is the greatest challenges facing homeland security and domestic intelligence for the next decade?”

I would say that this is the common (found both at home and abroad) anti-change/anti-modern “Dark Ages” movements — movements that have become manifest, post-the Cold War, throughout much of the world and, now, even here in the U.S./the West.

Why so dangerous? Consider the following from Deng Xiaoping’s reflection on China’s “Century of Humiliation:” “The backward will be beaten.”

The primary homeland security problem that we are facing today is the fact that a significant percentage of our population, re: their goals, their raison d’etre and their associated agendas, have more in common with certain of our opponents than they do with the rest of America’s population.

Explanation:

In this regard:

a. First consider the following re: President Putin of Russia and

b. Then ask yourself whether many Americans (a) significantly agree with these such concepts and (b) are prepared to take action to see that this such cause, and this such agenda, are likewise brought to fruition here in the United States:

“In his annual appeal to the Federal Assembly in December 2013, Putin formulated this ‘independent path’ ideology by contrasting Russia’s ‘traditional values’ with the liberal values of the West. He said: ‘We know that there are more and more people in the world who support our position on defending traditional values that have made up the spiritual and moral foundation of civilization in every nation for thousands of years: the values of traditional families, real human life, including religious life, not just material existence but also spirituality, the values of humanism and global diversity.’ He proclaimed that Russia would defend and advance these traditional values in order to ‘prevent movement backward and downward, into chaotic darkness and a return to a primitive state.’ ”

(See the Wilson Center publication “Kennan Cable No. 53” and, therein, the article “Russia’s Traditional Values and Domestic Violence,” by Olimpiada Usanova, dated 1 June 2020.)

Bottom Line Thought — Based on the Above:

If we can see and understand that such things as Russian New Generation Warfare are based on finding, or forming, “common cause” with the military and civilian populations of other states and societies:

“Thus, the Russian view of modern warfare is based on the idea that the main battlespace is the mind and, as a result, new-generation wars are to be dominated by information and psychological warfare, in order to achieve superiority in troops and weapons control, morally and psychologically depressing the enemy’s armed forces personnel and civil population.”

(See Janis Berzins, “Russia’s New Generation Warfare in Ukraine,” National Defense Academy of Latvia, April 2014, Page 5.)

Then we can likewise see and understand that:

a. The bond that Putin is forming with certain Americans (et. al)

b. Who likewise see such things as globalization (and those who sponsor same) as undermining their traditional values (and, accordingly, their status, privileges and protections derived from same)

c. How THIS has become the primary homeland security problem that we, and others, face today.

As further evidence in support of my suggestion above, consider the following:

First, as per our civilian population:

“Compounding it all, Russia’s dictator has achieved all of this while creating sympathy in elements of the Right that mirrors the sympathy the Soviet Union achieved in elements of the Left. In other words, Putin is expanding Russian power and influence while mounting a cultural critique that resonates with some American audiences, casting himself as a defender of Christian civilization against Islam and the godless, decadent West.”

(See the “National Review” item entitled: “How Russia Wins” by David French.) And:

Next, as per our military forces:

“Russian efforts to weaken the West through a relentless campaign of information warfare may be starting to pay off, cracking a key bastion of the U.S. line of defense: the military. While most Americans still see Moscow as a key U.S. adversary, new polling suggests that view is changing, most notably among the households of military members.”

(See the “Voice of America” item entitled: “Pentagon Concerned Russia Cultivating Sympathy Among U.S. Troops” by Jeff Seldin.)

In offering No. 2 by Jonathan Miller above, he notes — as the values that we Americans hold most dear — (from our Declaration of Independence) “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

In 1981, then-LTG Andrew Goodpaster — in a paper that he authored at that time entitled “Development of a Coherent American Strategy: An Approach” (see Page 4) — looked more to our Constitution and, therein, more to the Preamble thereof; this, to address, (a) not only preeminent American values but, indeed, (b) our responsibilities relating thereto:

“The starting point, I have long felt, must an identification and a clarification of basic American values that are at risk and must be protected at all costs. My friend and former boss, General Maxwell Taylor, put it this way: The job of military forces is to protect our “national values.” What are these national values. I think they can sufficiently be identified in the terms in which they are set down in the Preamble to our Constitution: “To … establish justice, ensure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our prosperity … .”

We proceed from that to examine who those values seem to be at risk in today’s international arena. There is risk to the safety of our people and our homeland. There is risk to our commerce, to our industry, to our economic well-being. There is risk to the ideals of freedom and human dignity on which our country is founded. And it becomes our task to find ways to deal with those risks, to assure safety for our people and for our commerce, and to guard ourselves against outside interference or coercion that would deny us the ability to determine our own way of life.”

The famous 1950 national security document “NSC-68” also took special care to quote the Preamble to our Constitution (in NSC-68, see Section II, “The Fundamental Purpose of the United States”):

“The fundamental purpose of the United States is laid down in the Preamble to the Constitution: ‘. . . to form a more perfect Union, establish justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.’ In essence, the fundamental purpose is to assure the integrity and vitality of our free society, which is founded upon the dignity and worth of the individual.”

NSC-68 also tries to help us understand what this Preamble actually means re: our homeland and national security responsibilities. Here are what appears to be some of its such “explanatory” statements:

First, from Section IV — “The Underlying Conflict in the Realm of ideas and Values Between the U.S. Purpose and the Kremlin Design” — therein, see Paragraph B, “Objectives:”

“The objectives of a free society are determined by its fundamental values and by the necessity for maintaining the material environment in which they flourish. …”

Next, from Section VI — “U.S. Intentions and Capabilities–Actual and Potential” –therein, see Paragraph A, “Political and Psychological:”

“Our overall policy at the present time may be described as one designed to foster a world environment in which the American system can survive and flourish. It therefore rejects the concept of isolation and affirms the necessity of our positive participation in the world community.

This broad intention embraces two subsidiary policies. One is a policy which we would probably pursue even if there were no Soviet threat. It is a policy of attempting to develop a healthy international community. …”

Bottom Line Questions — Based on the Above:

The values and related responsibilities — that the authors of NSC-68 put forward as early as 1950 — and that then-LTG Goodpaster pointed to in 1981 — can we say (with a straight face) that these are the same values, and the same responsibilities relating thereto, that have guided our national leadership’s actions of late?

If not, then can we consider that the deviations that have been made — from these hallowed values and responsibilities of late — suggest that that our national leadership is headed — re: such things as homeland and national security — in the wrong, or in the right, direction?

As an old graybeard (I’m in my 70’s now), I frequently find myself, these days especially, reflecting on this from my son’s Ranger Handbook:

“4. Tell the truth about what you see and what you do. There is an army depending on us for correct information … .”

From this perspective, I have come to be concerned that — re: such things as homeland security and national security today — “the truth” has come to be less important today and, indeed, has come be seen, by some, as a liability.

To help deal with this matter, I suggest that we (the Army) step forward to, for example,

a. First address the “permanently operating front” that Russian General Gerasimov describes here:

“… Asymmetrical actions have come into widespread use, enabling the nullification of an enemy´s advantages in armed conflict. Among such actions are the use of special operations forces and internal opposition to create a permanently operating front through the entire territory of the enemy state, as well as informational actions, devices, and means that are constantly being perfected. …”

(See the Army University Press, Sep-Oct 2020 edition of Military Review and, therein, the article “Russian New Generation Warfare: Deterring and Winning at the Tactical Level,” by James Derleth)

And:

b. Next consider whether the phenomenon described below may, in fact, constitute such a “permanently operating front:”

“Compounding it all, Russia’s dictator has achieved all of this while creating sympathy in elements of the Right that mirrors the sympathy the Soviet Union achieved in elements of the Left. In other words, Putin is expanding Russian power and influence while mounting a cultural critique that resonates with some American audiences, casting himself as a defender of Christian civilization against Islam and the godless, decadent West.”

(See the “National Review” item entitled: “How Russia Wins” by David French.)

“Russian efforts to weaken the West through a relentless campaign of information warfare may be starting to pay off, cracking a key bastion of the U.S. line of defense: the military. While most Americans still see Moscow as a key U.S. adversary, new polling suggests that view is changing, most notably among the households of military members.”

(See the “Voice of America” item entitled: “Pentagon Concerned Russia Cultivating Sympathy Among U.S. Troops” by Jeff Seldin.)

Bottom Line Thought — Based on the Above:

As members of the U.S. Army (me: retired), we have to be willing, I believe, to “bite into” the truth — and to consider our recommendations, etc., from the standpoint of same.

In this regard, can we actually say that we have — with a proper degree of enthusiasm, effort and scholarship — “bitten into” the matters that I describe above?

(As to the importance of such an effort, one need on reflect on the fact that, today, Putin, et. al, may well have:

a. WITH the use of a “permanent operating front,” such as I describe above, and thus

b. WITHOUT the use of ANY tanks, battleships, nuclear weapons, combat aircraft, etc.,

c. Came as close as anyone every has in harming, and/or destroying, our country and our democracy?)

At this late date, let me pose for consideration one more thought re: “2020: What’s Next?”

This being that NOTHING sets off the “honor, interest and fear” dynamite — at home or abroad — as quickly and as thoroughly as does:

a. The threat that the promotion of global capitalism

b. Poses to standing international, state and societal “orders.”

(The advance of capitalism requires “creative destruction”/requires that “the old be destroyed before the new can take over” — see the Schumpeter quote at my December 4th offering above.)

Now to consider that:

a. Such was the case with the advance of global capitalism in the decades prior to World War I. And that:

b. Such also appears to be the case with the advance of global capitalism in the decades of the post-Cold War.

(In both cases, [a] the advance of global capitalism works to undermine the existing international, state and societal orders of the day and, thus, [b] tends to lead to civil and international wars?)

Bottom Line Question — Based on the Above:

If, as I suggest above, today resembles the period before World War I,

Then should we know, accordingly, “what’s next?” (And, thus, what we must prepare for?)

I’m grateful for the knowledge and insights you’ve shared in this article. It was a great read.