Military strategy depends on geography to a far greater degree than what is currently practiced or taught.

One of the effects of the diminished attention to military strategy as warmaking has been to focus the efforts of military strategists on crafting or sorting out objectives. The favorite gripe of military professionals, even in military strategic positions, is that all the best tactical or operational efforts in the world cannot make up for poor or unclear political or strategic guidance. But this complaint, however true, does nothing to improve the crafting and execution of war or theater of war efforts. In fact, it is almost always buck passing–based on the assumption that the military is fundamentally good at all military tactics, operations, and strategy, so any failures must lay in the political arena. Failure couldn’t possibly be the military’s fault. This line of thinking incorrectly absolves military strategists of taking responsibility for their work and it neglects important deficiencies in contemporary military strategy, especially around problems of military geography.

Military strategy depends on geography to a far greater degree than what is currently practiced or taught. Even if military strategists go past ends in the oversimplified heuristic and get into the ways and means, neither of those categories encourages a greater focus on the unique characteristics of geography as a key factor of making military strategy. To the limited degree that military strategy—that is, strategy for warmaking—is delineated in contemporary theory and doctrine, the absence of attention on traditional geography is evident. For example, Joint Publications 1 (Doctrine for the U.S. Armed Forces), 3-0 (Joint Operations), and 5-0 (Joint Planning) use the words “geography” and “terrain” hardly at all, and “geographic” primarily as a modifier in front of “combatant command.” Where geography plays its more traditional role, it is part of assessing or framing the environment—but a very small part. Perhaps because of the last few decades of counterinsurgency-type fights, understanding the strategic environment in American military strategic theory and doctrine has become heavily focused on peoples and cultures, best evidenced by the attempts to map the so-called “human terrain.”

If physical geography has a place in military affairs, it is generally in military intelligence, and there it is shunted off to geospatial sub-specialists. The older concept of geopolitics, which directly related features of physical geography to concepts of political, military, and naval advantage in peace, became a sort of synonym for so-called realist approaches to international relations, losing its focus on physical characteristics, which is why Robert Kaplan needed to write about The Revenge of Geography in 2012. As a result, a deeper understanding and application of military geography is not a part of the study, practice, planning, or even execution of war for senior military professionals responsible for military strategy. That is a mistake.

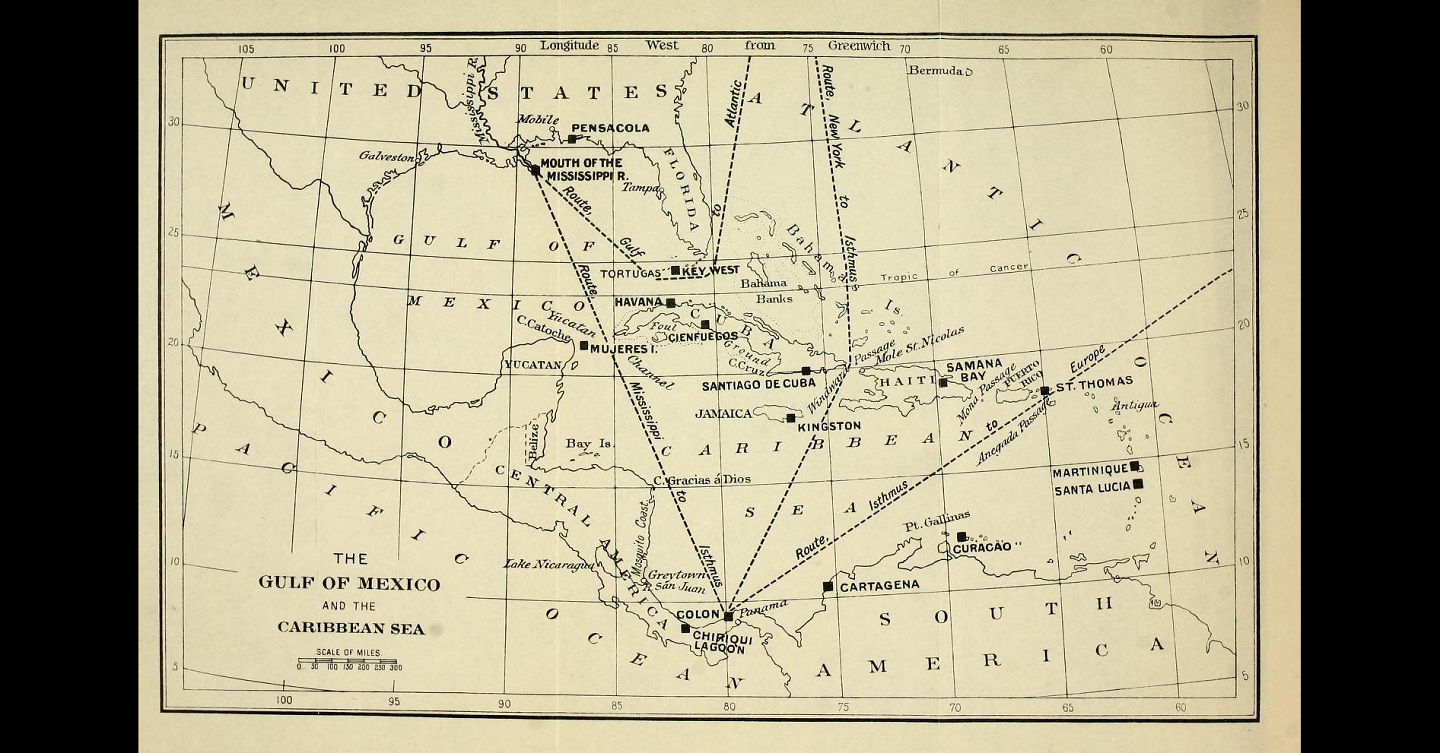

It wasn’t always this way. Geography, terrain, water topography and hydrography, atmospherics, and other physical conditions are all obviously important at the tactical level. Those features are just as essential to warmaking for military strategists, but in different ways. A great example comes from none other than Alfred Thayer Mahan, and it is not (for once) Influence of Sea Power Upon History and its interpretations. His “Strategic Features of the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean” first appeared in Harper’s Magazine in 1897, based on lectures he gave at the U.S. Naval War College in 1887. His discussion was updated and expanded in a book called Naval Strategy, published in 1911 (an edited version is here).

Mahan began with the idea of that the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean were crossroads of vital importance in international affairs. He called them “points of supreme interest to all mankind,” because they linked the Mississippi River valley, Atlantic Ocean, and Pacific Ocean, through the Panama Canal (p. 304). For economic, security, and ideological (i.e., the Monroe Doctrine) reasons, these areas were especially important to the United States. Notably, those economic, security, and ideological reasons were not the “strategic features” of the Gulf and Caribbean, and Mahan does not call them “strategic.”

Rather, the “strategic features” that Mahan identified related to directly to warmaking. This word choice is important to the use of geography for military strategists. Yes, all surveys of physical strategic environments must begin with why a particular area is important in a broader security, economic, political, and security sense. And obviously all such surveys will provide an overview of the geographic characteristics of the area. But what made Mahan’s survey strategic, what made the geography military, was that he related geographic features to the conduct of wars.

In Mahan’s hands, the Gulf and Caribbean became a potential theater of war, with a particular emphasis on maritime operations. He used presumptive wars with great European fleets (British, French, and later German) and the actual war with Spain to drive his analysis. He identified where ships and fleets of various sizes could and would fight, calculating the geometry of distances and angles among key economic ports, sea lanes, chokepoints, defensible and indefensible harbors and ports, and the infrastructure and resources of the islands and other landmasses. Moreover, Mahan shifted perspectives, changing the relative weight of his considerations and observations based on various wartime scenarios—different belligerents on all sides controlling or contesting different islands and sea lanes.

The idea here is not to summarize all of Mahan’s survey, but rather to note that his close consideration of what the geographic features of the Gulf and Caribbean might mean for wars between the United States and other powers clarifies many things. For one, the course, conduct, and outcome of the 1898 Spanish American War in the region makes far greater sense. The military geography fundamentally shaped the why, who, when, and how of the joint naval and military campaigns in the war—the essential work of military strategists.

If military strategists gripe about not having clear political objectives, the corollary gripe of policymakers is that they need military options…

For another, in doing the military strategic work of determining what geographic features were most important in war, Mahan’s survey enabled and acted as an example of actual military advice. If military strategists gripe about not having clear political objectives, the corollary gripe of policymakers is that they need military options—that is, they need a clear articulation of what is possible and likely in a given scenario. Providing policymakers and diplomats with a clearer perspective of what was militarily important in the region in war thus informs the making of policy and the conduct of diplomacy in peace and war. And the geographic analysis is durable in a way that other elements of military strategy, for example, weapons or personnel strength, are not. Hold up Mahan’s survey with any number of specific political or diplomatic actions in the area and the alignment is remarkable. There is no better example than the American seizure and maintenance of the naval base at Guantanamo Bay, even after Cuba fell to Fidel Castro’s communists in 1959. The Windward Passage is the main gateway between the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean, Gulf of Mexico, and the Panama Canal. The region’s security in peace and war depends upon some measure of control of the Windward Passage, which runs between Haiti and Cuba—and right by Guantanamo Bay.

Lest such studies seem only to be the work rare elite military theorists, Mahan had plenty of company among American military officers in looking at what the physical geographic environment meant for warmaking. For example, in the 1890s, instructors at what would eventually become the Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth delivered lectures on the military geography of Canada, Chile, Mexico, and Central America, published together in 1895. Led by Arthur Wagner and Eben Swift, these army officers took much the same approach as Mahan, only with a greater but by no means exclusive focus on land war.

Like Mahan, thinking through potential wars in these regions made their analyses of the geography matters of military strategy. Wagner said it best:

Hence arises the importance of the study of military geography; which may be described as the study of geography with reference to the operations of armies; and which from its very nature, necessarily embraces many features of political as well as physical geography.

To a student of the Art of War, the study of the military geography of any country is an interesting one; but it is, perhaps, only when the study is applied to countries whose interests are closely bound to our own, whose foreign policy may clash with that of the United States, and whose territories may be the theatre of operations of our armies—or to those parts of our own land which may feel the tread of the invader—that it becomes to us a study of importance second to no branch of the Art of War (p. 6).

These officers were not looking to pick fights with Canada, Mexico, Chile, or Central America. But given the international situation at the time and American interests and professed policies—again, the Monroe Doctrine—it was only prudent, and indeed the literal job of the military, to prepare for such wars.

Summarizing their findings is not the aim of this essay, but as with Mahan, the military geographic analyses explain much about that era and beyond, in both war and peace. For instance, the military geography, not just in terms of usable ports and lines of operations, but also in proximity and access to important objectives, all but dictated that when the United States intervened in the Mexican Revolution in 1914 it would be at Veracruz. Or consider the American relationship to Great Britain at the time. In that historical moment, tensions with Great Britain were far greater than most remember, but part of the reason they never boiled over into full scale war was because of the military geography. The American-Canadian frontier, especially in relation to key strategic objectives (political, economic, military) and the military and naval capabilities of both sides, made offensive operations difficult in the best of times and all but impossible in winter. Neither side wanted that fight, and it never happened.

Over the next half century, the United States military did prepare for wars around the globe—in the United States and with or in Canada and with Great Britain; as well as in Mexico, Caribbean countries, and South America; and eventually with Japan in regions around the Pacific Ocean. And they did so while studying the military geography in much the same manner as Mahan, Wagner, and the rest. Which brings this discussion to its most important point. Even as military mapping increasingly fell into the domain of specialist intelligence or engineer staff sections in the first half of the twentieth century, that did not mean military geography was left to theorists, military instructors, and niche experts.

The education of future Army military strategists used to involve the individual preparation of military geography studies or committee strategic surveys based on military geography. At Fort Leavenworth, students wrote paper after paper on the subject, looking at regions all over the world. At the Army War College, military strategic surveys of the United States and a wide variety of potential theaters of war were a regular feature of the work. For example, Dwight Eisenhower produced reports looking at the eastern United States and Mexico during his year. Similar work went on at the Naval War College.

The practice was of great value. In his wartime memoir, Eisenhower told the story of arriving at the General Staff and being tasked by George C. Marshall to look at the worldwide situation, focusing on the Pacific and the Philippines, to determine “What should be our general line of action?” Eisenhower spent the next few hours coming to his answer, depicted in a couple of succinct pages focused almost entirely on the military geography of the theater (pp. 16-22). The rest, as they say, is history.

These days there are plenty of excellent studies on military geography. John Collins’ classic book on the subject still holds up. A new article by a geographer about supplying the Nashville Depot during the Civil War ought to cause a reassessment of all strategies in that theater. And at least two recent studies in the Naval War College Review explicitly used Mahan’s Gulf and Caribbean survey as a model for looking at regions in the Pacific. The geography of air, space, and even cyberspace also get attention from experts.

Military strategists should read Mahan, Wagner, and these newer works. But they must also learn to do the work themselves. The value in strategic surveys of military geography for military strategists is in the complex thought processes that go into putting together such surveys themselves. The agility Eisenhower displayed in answering Marshall’s requirement came from already doing such thinking. Today’s military officers should learn and practice to do the same.

Thomas Bruscino is anAssociate Professor in the Department of Military, Strategy, Planning and Operations at the U.S. Army War College and the Editor of the DUSTY SHELVES series.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Alfred Thayer Mahan’s Gulf and Caribbean survey

Photo Credit: Mahan, Interest of America in Sea Power, Present and Future, 1897, p. 270

WAR ROOM releases by Thomas Bruscino:

- GRAND STRATEGY: A SHORT GUIDE FOR MILITARY STRATEGISTS

- THE FUTURE IS EXPEDITIONARY: JOINT WARFIGHTING HQ

- PAST VISIONS OF FUTURE WARS

- REFLECTIONS ON MILITARY STRATEGY: KILLING ANNIHILATION VS. ATTRITION

- START WITH BOOK THREE: FINDING UTILITY IN CLAUSEWITZ’S ON WAR

- THAT NEVER HAPPENED: A WATER COOLER DISCUSSION ABOUT MOVIES

- THE LEAVENWORTH HERESY?

- BOOK LOVERS NEED APPLY: A DUSTY SHELVES PODCAST

- DUSTING OFF THE DUSTY SHELVES