Grand strategy is an elusive beast. Everybody wants some. We all agree it’s important but nobody can agree exactly what it is. And everybody wants to teach about the topic. A BETTER PEACE welcomes Christopher McKnight Nichols and Andrew Preston to the virtual studio, who along with Elizabeth Borgwardt, have edited a fascinating new essay collection Rethinking American Grand Strategy from Oxford University Press. The two join podcast editor Ron Granieri to discuss the how the book came about, and their contributions to the grand strategy conversation.

We want to provide a kind of usable history that is spot on in terms of the factual basis, which is why we brought these great historians to the topic and then kind of plant the seeds for practitioners and other folks and just general readers.

Podcast: Download

Christopher McKnight Nichols is an American historian. He is the Director, Center for the Humanities, Sandy and Elva Sanders Eminent Professor in the Honors College, Associate Professor of History, Oregon State University. He is the author of Promise and Peril: America at the Dawn of a Global Age.

Andrew Preston is Professor of American History at Cambridge University, where he is also a Fellow at Clare College. His most recent book is American Foreign Relations: A Very Short Introduction.

Ron Granieri is an Associate Professor of History at the U.S. Army War College and the Editor of A BETTER PEACE.

The views expressed in this presentation are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

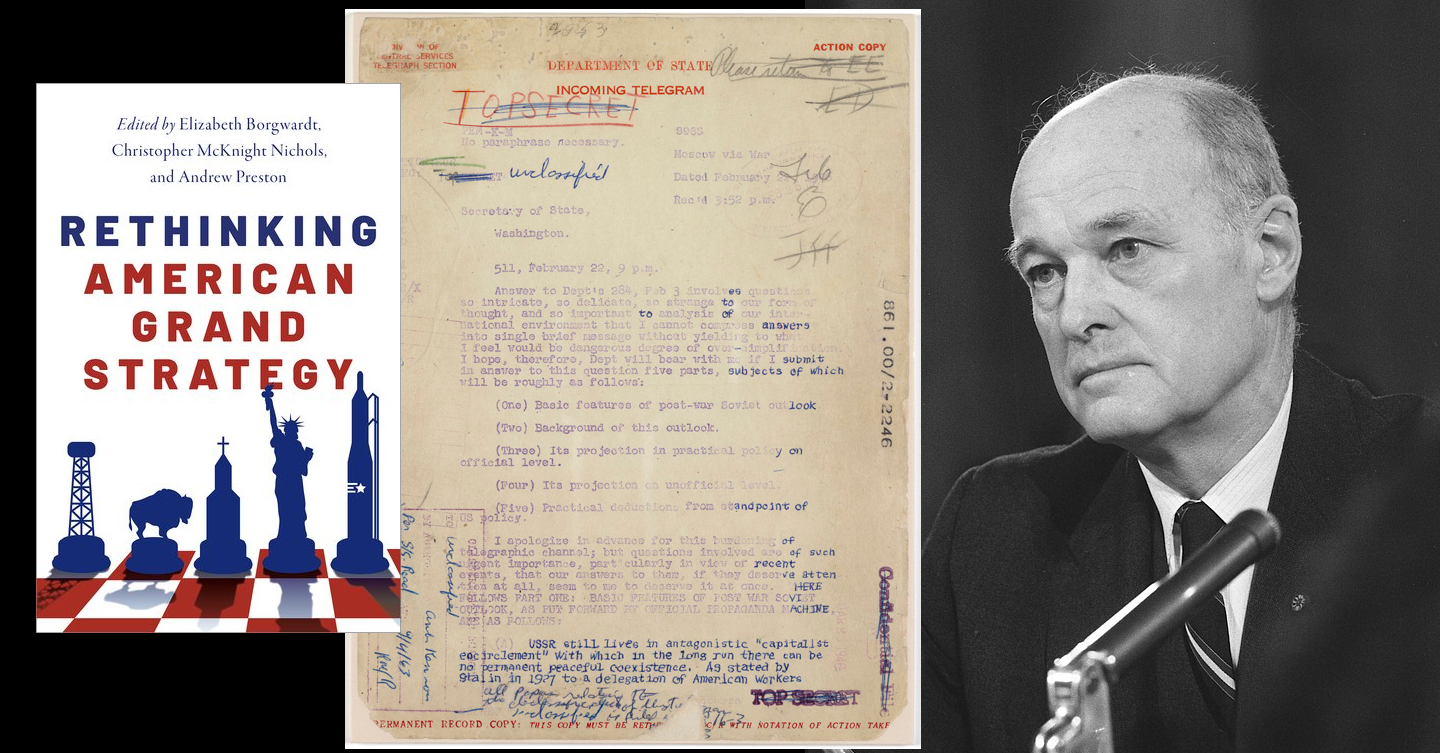

Photo Description: Written in 1946 by George Kennan (r), the American charge d’affaires in Moscow, the Long Telegram (c) was an 8,000 word document outlining his views on the Soviet Union and was a foundational document of the U.S. Cold War policy of containment.

Photo Credit: Images courtesy of the National Archives Catalog, and the Library of Congress, photographer Warren K. Leffler.

Based on recent — but also long-running from a historical perspective — events, we should probably consider grand strategy more along the “rural versus urban”/”traditional versus modern” lines I have outlined, with my examples, below:

First, an Afghanistan example of this “rural versus urban”/”traditional versus modern” clash:

“If the history of Afghanistan is one great stage play, the United States is no more than a supporting actor, among several previously, in a tragedy that not only pits tribes, valleys, clans, villages and families against one another, but, from at least King Zahir Shah’s reign (Afghanistan’s first “modernizer?”), has violently and savagely pitted the urban, secular, educated and modern of Afghanistan against the rural, religious, illiterate and traditional.”

(Item in parenthesis above is mine. See Matthew Hoh’s resignation letter as provided by the Washington Post.)

Next, a recent U.S./Western example this “rural versus urban”/”traditional versus modern” clash phenomenon:

“The earthquake that elected Donald Trump has left the United States approaching 2020 with a political landscape reminiscent of 1920. Not since then has the cultural chasm between urban and non-urban America shaped the struggle over the country’s direction as much as today. Of all the overlapping generational, racial, and educational divides that explained Trump’s stunning upset over Hillary Clinton last week, none proved more powerful than the distance between the Democrats’ continued dominance of the largest metropolitan areas, and the stampede toward the GOP almost everywhere else.”

(See the “Atlantic” article entitled: “How the Election Revealed the Divide Between City and Country, by Ronald Brownstein.)

Last, a final Afghanistan example of this such phenomenon:

“Having spoken with members of rural communities and the weary survivors of Afghanistan’s numerous conflicts, I sought the opinion of a different demographic: young city-dwellers that have a different perspective from their forebears. In the opinion of one young Uzbek I spoke to in Kabul, it is the duty of all Afghans to be united under a single country and state. For a Hazara in her mid-20s, the goal was to get a college degree and eventually run her own business. Such a dream could only become a reality under the current government in Kabul. And for a young male Pashtun who ran a local enterprise in the city, the Pashtunwali and the strict interpretation of Islam belonged to the countryside, not in places like Kabul.”

(From the STRATFOR article: “Deciphering the Taliban,” by Diego Solis)

Bottom Line Thought — Based on the Above:

Today, much as in other times throughout history, countries (to include not just Afghanistan but also the U.S./the West) must make hard choices; this, between “urban versus rural” and “traditional versus modern;” choices which — sooner or later — decide their fate. In this regard, consider this example from Andrew Jackson time:

“Jacksonians drew their support from Northern laborers and yeoman farmers in the South and in the West. These groups, which Jackson dubbed the ‘bone and sinew of America,’ worried that the market economy would force them into the dependent class. The Jacksonians told the farmers and the laborers that they would do everything in their power to prevent this from taking place. In essence, the men and their rank and file voting allies, along with Jackson, fought a rear-guard action against encroaching industrialization and market economy. Although they won the pivotal battles, they lost the war, because their notion of a pre-capitalist agrarian society succumbed to the industrial economy after the Civil War.”

(See the ‘Encyclopedia of U.S. Political History’ by Andrew Robertson, et al., and the section therein entitled ‘Jacksonian Democracy,’ Page 194.)”

Today, might we say, such things as the information revolution and the global economy force the “traditional versus modern” choice that each state and its societies must make?

Grand strategy, thus, needing to be pointed in one (tradition = ultimate defeat) or the other (modern = ultimate victory] direction?

From this perspective, of course, the main job of “strategy” — both at home and abroad — this would be “selling modernity” and, thus, “selling necessary political, economic, social and value change?”

From the “Description” tab found at the link to the “Rethinking American Grand Strategy” book in the paragraph above:

“What is grand strategy? What does it aim to achieve? And what differentiates it from normal strategic thought–what, in other words, makes it ‘grand’? In answering these questions, most scholars have focused on diplomacy and warfare, so much so that ‘grand strategy’ has become almost an equivalent of ‘military history.’ The traditional attention paid to military affairs is understandable, but in today’s world it leaves out much else that could be considered political, and therefore strategic. It is in fact possible to consider, and even reach, a more capacious understanding of grand strategy, one that still includes the battlefield and the negotiating table while expanding beyond them. Just as contemporary world politics is driven by a wide range of non-military issues, the most thorough considerations of grand strategy must consider the bases of peace and security–including gender, race, the environment, and a wide range of cultural, social, political, and economic issues.”

At first glance, one might not see the hard-core connection — between (a) “cultural, social, political, and economic issues, etc.” and (b) such things as “grand strategy,” “diplomacy and warfare,” “military history,” and “the battlefield and the negotiating table.”

However, when one considers that (a) the political, economic, social and value “change” requirements of various types of “modernization” (for example, along communist lines and/or as relates to modern capitalist/globalization requirements), this is (b) often the “root cause” of the development and deployment of such things as “grand strategy,” “diplomacy and warfare,” “military history,” and “the battlefield and the negotiating table,” then this such iron-clad nexus becomes much more clear. Yes?

(This, for example, whether we are talking about domestic and/or foreign policy, and/or about the American Civil War, the Old Cold War, and/or our current problems/difficulties at home and/or abroad — all of which, in one way or another, come about because of the threat — and requirement — for various political, economic, social and value change/modernization?)

So, based on my thoughts above, now would seem to be the time to ask this seemingly critical question; this being:

Just how central is (or should be) the concept of political, economic, social and/or value “change” (and resistance to such “change”) — or, if you prefer, the concept of “revolution” (and resistance to such “revolution”) — this, to any important discussion of “grand strategy”?

In this regard, consider the following items — which are provided in effort to cause us to explore, much more carefully and much more thoroughly — the question that I ask immediately above:

“The United States and the Soviet Union face each other not only as two great powers which in traditional ways compete for advantage. They also face each other as the fountain heads of two hostile and incompatible ideologies, systems of government and ways of life, each trying to expand the reach of its respective political values and institutions and to prevent the expansion of the other. Thus the cold was has not only been a conflict between two world powers but also a contest between two secular religions. And like the religious wars of the seventeenth century, the war between communism and democracy does not respect national boundaries. It finds enemies and allies in all countries, opposing the one and supporting the other regardless of the niceties of international law. Here is the dynamic force which has led the two superpowers to intervene all over the globe, sometimes surreptitiously, sometimes openly, sometimes with the accepted methods of diplomatic pressure and propaganda, sometimes with the frowned-upon instruments of covert subversion and open force.” (From Hans Morgenthau’s “To Intervene or Not to Intervene.”)

“For the past three decades, as the United States stood at the pinnacle of global power, U.S. leaders framed their foreign policy around a single question: What should the United States seek to achieve in the world? Buoyed by their victory in the Cold War and freed of powerful adversaries abroad, successive U.S. administrations forged an ambitious agenda: spreading liberalism and Western influence around the world, integrating China into the global economy, and transforming the politics of the Middle East.” (From “Foreign Affairs” (the Mar/Apr 2020 issue), the article therein by Jennifer Lind and Daryl G. Press entitled “Reality Check: American Power in an Age of Constraints.”)

“Robert Egnell: Analysts like to talk about ‘indirect approaches’ or ‘limited interventions’, but the question is ‘approaches to what?’ What are we trying to achieve? What is our understanding of the end-state? In a recent article published in Joint Forces Quarterly, I sought to challenge the contemporary understanding of counterinsurgency by arguing that the term itself may lead us to faulty assumptions about nature of the problem, what it is we are trying to do, and how best to achieve it. When we label something a counterinsurgency campaign, it introduces certain assumptions from the past and from the contemporary era about the nature of the conflict. One problem is that counterinsurgency is by its nature conservative, or status-quo oriented – it is about preserving existing political systems, law and order. And that is not what we have been doing in Iraq and Afghanistan. Instead, we have been the revolutionary actors, the ones instigating revolutionary societal changes. Can we still call it counterinsurgency, when we are pushing for so much change?” (From the Small Wars Journal article “Learning From Today’s Crisis of Counterinsurgency” by Octavian Manea — an interview with Dr. David H. Ucko and Dr. Robert Egnell.)

“Within the existing framework of international law, is it legitimate for an occupying power, in the name of creating the conditions for a more democratic and peaceful state, to introduce fundamental changes in the constitutional, social, economic, and legal order within an occupied territory? … These questions have arisen in various conflicts and occupations since 1945 — including the tragic situation in Iraq since the United States–led invasion of March–April 2003. They have arisen because of the cautious, even restrictive assumption in the laws of war (also called international humanitarian law or, traditionally, jus in bello) that occupying powers should respect the existing laws and economic arrangements within the occupied territory, and should therefore, by implication, make as few changes as possible.” (See the first two paragraphs of Sir Adam Roberts’ “Transformative Military Occupations: Applying the Laws of War and Human Rights.”)

“Liberal democratic societies have, in the past few decades, undergone a series of revolutionary changes in their social and political life, which are not to the taste of all their citizens. For many of those, who might be called social conservatives, Russia has become a more agreeable society, at least in principle, than those they live in. Communist Westerners used to speak of the Soviet Union as the pioneer society of a brighter future for all. Now, the rightwing nationalists of Europe and North America admire Russia and its leader for cleaving to the past.” (From “The American Interest” article “The Reality of Russian Soft Power” by John Lloyd and Daria Litinova.)

“a. An IDAD (Internal Defense and Development) program integrates security force and civilian actions into a coherent, comprehensive effort. Security force actions provide a level of internal security that permits and supports growth through balanced development. This development requires change to meet the needs of vulnerable groups of people. This change may, in turn, promote unrest in the society. The strategy, therefore, includes measures to maintain conditions under which orderly development can take place.” (Item in parenthesis above is mine.) (From our own Joint Publication 3-22, Foreign Internal Defense; therein, see Chapter II, Internal Defense and Development Program, Paragraph 2, “Construct.”)

In addition to the “grand strategy” matters that I have attempted to present above, consider the similarity between the three quoted items I provide below. Note therein, for example, the suggested internal conflict (in both the U.S. and China?) between what Walter Russell Mead calls “market society” and “community:”

“In this new world disorder, the power of identity politics can no longer be denied. Western elites believed that in the twenty-first century, cosmopolitanism and globalism would triumph over atavism and tribal loyalties. They failed to understand the deep roots of identity politics in the human psyche and the necessity for those roots to find political expression in both foreign and domestic policy arenas. And they failed to understand that the very forces of economic and social development that cosmopolitanism and globalization fostered would generate turbulence and eventually resistance, as ‘Gemeinschaft’ (community) fought back against the onrushing ‘Gesellschaft’ (market society), in the classic terms sociologists favored a century ago.”

(From the Mar-Apr 2017 edition of “Foreign Affairs” and, therein, the article “The Jacksonian Revolt: American Populism and the Liberal Order” by Walter Russell Mead.)

“All in all, the 1980s and 1990s were a Hayekian moment, when his once untimely liberalism came to be seen as timely. The intensification of market competition, internally and within each nation, created a more innovative and dynamic brand of capitalism. That in turn gave rise to a new chorus of laments that, as we have seen, have recurred since the eighteenth century: Community was breaking down; traditional ways of life were being destroyed; identities were thrown into question; solidarity was being undermined; egoism unleashed; wealth made conspicuous amid new inequality; philistinism was triumphant.”

(From the book “The Mind and the Market: Capitalism in Western Thought” by Jerry Z. Muller; therein, see the chapter on Friedrich Hayek.)

“Compelling as it may seem, this argument, too, has some empirical difficulties: Until the past few years, the dominant socioeconomic or political positions in the Chinese intellectual world were clearly liberal ones: most intellectuals argued for greater institutional restraints on state activity, free market reforms, and stronger protection of civil and political rights. Even today, Pan and Xu’s paper finds that highly educated individuals are generally more liberal than less educated ones. When cultural conservatism reemerged as a somewhat influential ideological position during the later 1990s, its proponents could arguably reap greater social benefits by developing a liberal affinity, rather than a leftist one. For the most part, this did not happen.

Why not? Reading the early work of prominent contemporary Neo-Confucian intellectuals such as Jiang Qing or Chen Ming, one feels that this was a carefully considered — even principled — decision: They saw themselves as defending Chinese traditions against a distinctly hostile Western liberal intellectual mainstream. The ‘other’ they defined themselves against was not some version of socialism or leftism, which at this time was clearly a minority position, but rather a supposedly intolerant liberalism that had dominated Chinese sociopolitical thought since the 1980s.”

(From the 2015 “Foreign Policy” article “What it Means to Be ‘Liberal’ or ‘Conservative’ in China: Putting the Country’s Most Significant Political Divide in Context” by Taisu Zhang.)

Bottom Line Questions — Based on the Above:

From a national security perspective, when the “enemy”/the “other” is seen — in both one’s own country and abroad — as those entities who are pressing for political, economic, social and/or value “change” (this, so as to better provide for “market society” and, this, at the clear expense of “community”), then:

a. In what direction (toward “market society” or “community”) does “grand strategy” go? And:

b. Who (“market society” or “community”) does “grand strategy” service/provide for (at the clear expensive of the other)?