The United States Army War College is on a multi-year endeavor to develop a wargame that reinforces our curriculum and provides students with repetitions building campaigns in crisis and conflict—education that includes practice and performance.

In 1914, a Scientific American correspondent recorded his impressions of a wargame at the United States Army War College (USAWC):. “The officers studying the map … are not playing. The very title of the game is misleading. It is most decidedly not a game … And it is not played as a game, to see who will win, but to get results and experience, to profit by the very mistakes made.” Even a century ago, the Army War College understood the educational value of wargaming.

The USAWC is on a multi-year endeavor to develop a wargame that reinforces our curriculum and provides students with repetitions building campaigns in crisis and conflict—education that includes practice and performance. Pedagogical wargames are typically rigid in nature, adhering to a strict ruleset, order of events, and timeline to simplify a complex combat environment within a compressed period. This inevitably presents two challenges: one, the game abstracts concepts to such a level that the scenario becomes detached from reality; and two, the “overhead” of the game and its rules become the focus, overwhelming the learning opportunities for both students and instructors.

In February 2024, Derek Martin and John Nagl described early efforts to use wargaming in the War College’s China Integrated Course (CIC). These rigid wargames with strict rules and onerous adjudication processes produced mixed results. During Academic Year 2026, a few seminars experimented with a simpler, tabletop-style exercise using large language models (LLMs) to speed adjudication. While looking back to the early 19th-century Prussian free-adjudication-style wargames, the team also looked forward by using artificial intelligence (AI) to help build detailed responses to student inputs. The result was a game that allowed students to focus on building operational plans and achieving learning outcomes rather than mastering artificial game rules. While not without its challenges, the results were universally positive, and the participating faculty deemed the game a success!

This problem of balancing reality with simplicity has historical precedent. Almost a century before the Scientific American visit to the USAWC, Lieutenant von Reisswitz of the Prussian Guard presented the Chief of the General Staff, General von Muffling, a game called Kriegsspiel. Though this wargame was popular in professional military settings, it met with resistance because it relied on a burdensome, rigid rule system. Several leaders in the field next developed “Free Kriegsspiel,”which simplified the system by removing much of the computational overhead. The new system asked game directors to adjudicate the outcomes of moves without depending on charts and tables, but instead using their expertise. This brought its own challenges, with some complaining that “there is no one here who understands how to conduct it rightly!”

Free-form adjudication has been widely applied, especially at the political and strategic levels. It relieves instructors and students of rigid rulesets, freeing them to focus on discussion of complex topics and learning outcomes. Yet the burden on faculty to “conduct it rightly” remains. LLMs can help reduce this burden, thus freeing instructors to focus on student learning.

Preparation and Conduct of the Game

Faculty deliberately prepared students for the Pacific Strategy exercise by incorporating multiple campaign planning iterations beforehand. During the Military Strategy and Campaigning (MSC) course, students conducted a day-long design exercise developing strategies to counter aggressive Chinese posturing in the Indo-Pacific. They also wrote a paper presenting military options for US Indo-Pacific command to respond to a Chinese attack on a Philippine Navy frigate and a U.S. aircraft carrier in the Philippine Sea. Students were then required to adopt the Chinese perspective when developing options for seizing Taiwan during the China Integrated Course’s lesson on the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) military capabilities.

Pacific Strategy progressively increases the tempo of the campaign—a Chinese invasion following a Taiwanese declaration of independence—over the wargame’s three days. Instructors control the event through a simple digital map that displays to students only their forces and whatever opposing forces they would have realistically identified. The first day simulates a six-month crisis in which both sides attempt to improve their posture for war. The second day has two turns, each simulating a month of activity with the Chinese invasion and the United States response. The third day simulates just 72 hours of fighting in two intensive turns before concluding with a discussion and review of the previous days’ events.

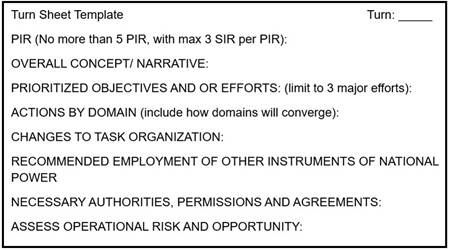

Each turn begins with the faculty issuing an intelligence report and orders from higher headquarters. The respective teams then have one hour to submit an intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance plan, which the faculty then use to reveal additional adversary units through an LLM-facilitated intelligence summary. Turns conclude with a 30-minute student briefing to the faculty, accompanied by a written concept of operations (usually 5-10 pages in length) and a map depicting the desired movement of units (see graphic below). Students also used an LLM to help them rapidly produce their plans, though most of the work remained manual.

Aided by an LLM, the faculty adjudicated the moves, updated the digital map, and gave oral and written feedback to the teams. One faculty member provided an immediate briefing of the major results while the rest of the team prepared a detailed report delivered to the students thirty to sixty minutes later. The faculty also provided guidance from higher before transitioning to the next turn.

Using AI to Support Adjudication

The adjudication process relied on faculty discussions fleshed out by an LLM. After receiving the students’ 30-minute briefing of their plan, the adjudicators met to discuss major results and run the student plans through the LLM with faculty-determined parameters to generate an operations and intelligence (O&I) summary.

After the student teams submit their respective turn sheets, the adjudicators upload each into the LLM that examines the student plans against preloaded material from the core courses at the USAWC. This includes the Pacific Strategy scenario book and each team’s privileged instructions. Using an “Open then Closed” approach, the adjudicators prompt the LLM to prioritize the course and scenario material, minimizing calls to internet data.

When the teams’ respective moves produced large-scale combat, the faculty team determined the outcome and the LLM produced battle damage assessments.

Next, the adjudicators use the LLM to analyze and find points of intersection or tension between the two plans and recommend an outcome. In the spirit of experimentation, during this first iteration adjudicators did not give the LLM guidance on criteria to determine the outcome, allowing it to determine for itself. It weighed the turn sheets on three tensions: (1) risk v. decisiveness, (2) multi-domain integration, and (3) alliance and international engagement. Although we did not set these parameters, they generally mirror the curriculum, and future faculty teams could create and upload spreadsheets identifying what the LLM should look for in the turn sheets, better clarifying how it should regulate its decision.The adjudicators next use the LLM’s discrete event simulation capability to create a realistic 6-month timeline of events resulting from the interaction of the two plans.

In addition to the timeline, the faculty uses the LLM to generate an O&I report for student teams that includes key events, enemy activity and other intelligence, conditions of the operational environment (weather, civilian population, etc.), and orders from national leaders. When the teams’ respective moves produced large-scale combat, the faculty team determined the outcome and the LLM produced battle damage assessments. The LLM cross-referenced the order of battle in the Pacific Strategy handbook and generated approximate losses for major units. For example, after the PLA team launched its assault on Taiwan, the LLM produced the following report:

- Southern landing was repelled with heavy PRC casualties—about 70% of the 2 amphibious brigades lost, effectively nullifying the southern assault. Southern task force engaged with a U.S. Surface Action Group, and there are indications of U.S. Special Forces supporting the coastal defense fires at Kaohsiung.

- Northern landings achieved a partial beachhead at Taichung seaport (~1 amphibious brigade at about 40% of original strength) and Taichung airport (1 airborne brigade+ consolidated after ~50% losses).

It is important to note that the adjudicators had to “train” the LLM to produce a suitable O&I. Human oversight was necessary to adjust outcomes and force students to manage specific situations to meet training objectives—like dedicating resources to recover a disabled ship. AI hallucinations occasionally occurred requiring instructor editing. The process became more efficient each turn as faculty refined the input and parameters, but human review remained a critical final step in producing the O&I.

Way forward

Information security was a concern throughout this exercise. For the pilot, teams started using a government-provided version of Ask Sage, which consistently froze and lost information. As such, all groups moved to commercial systems, including ChatGPT, Claude, and Grok, often relying on individual instructors’ paid subscriptions (i.e. ChatGPT o1). Despite being fictional scenarios, the wargames used real-world information that, while unclassified, could reveal sensitive patterns in U.S. cognitive approaches. To mitigate this risk, the military requires a robust LLM operating on a closed network. Exercise planners will benefit from building diverse faculty teams and robust capability guides to alleviate the age-old accusation that “there is no one here who can conduct it rightly!” in free-adjudication games. Questions like “How far can that aircraft carrier travel in 72 hours?” and “How many rounds of ammunition exist on Guam?” continually surfaced. Experienced faculty can quickly find this information, but having agreed-upon parameters available to all participants will speed up the adjudication process and prevent highly competitive students from calling foul!

Managing moves on the map was also a challenge. Faculty experimented with several methods to geographically depict the situation to students using a “home-built” wargaming toolkit application. Ultimately, we identified it as an area to improve, but for which there are viable solutions with modern user interfaces. Just as advances in precision cartography improved wargaming in the 19th and 20th centuries, so should our contemporary map provide a manageable, immersive environment.

While imperfect, Pacific Strategy was a step forward in the USAWC’s effort to develop a wargame simple enough to work for 400 students in 24 different seminars but realistic enough to “to get results and experience, to profit by the very mistakes made.” Simplifying the game allowed students to focus on planning, while employing AI in adjudication empowered faculty to “conduct it rightly” without sacrificing learning outcomes. As in all professional military education wargames, building diverse faculty teams that practice playing before introducing the game to students remains a critical task.

Thomas W. Spahr is the DeSerio Chair of Strategic and Theater Intelligence at the U.S. Army War College. He is a retired colonel in the U.S. Army and holds a Ph.D. in History from The Ohio State University. He teaches courses at the Army War College on Military Campaigning and Intelligence.

Layton Mandle is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Emerging Technology and Artificial Intelligence at the United States Army War College.

Mike Stinchfield is the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army War College. He was previously the Director of the National Security Simulation Exercise of Competition, Crisis, and Conflict (NSEC3), which is an Enhanced Program.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Credit: Adapted by AI from the original print Adalbert von Rössler Officers Playing a Kriegsspiel (circa 1880)

As a retired Army major who has spent decades hammering away at the rigid, industrial-age structures that hobble our military’s ability to adapt and win in the chaotic battlefields of the 21st century, I greet the innovative work of Tom Spahr, Layton Mandle, and Mike Stinchfield in “Back to the Basics in Wargaming – With a Little Help from AI” with a mix of enthusiasm and cautious optimism. Their article, published in the War Room on this poignant date of September 11, 2025, shines a light on the U.S. Army War College’s bold experiment with artificial intelligence (AI) to revive the spirit of 19th-century Free Kriegsspiel.

By leveraging large language models (LLMs) to streamline adjudication in pedagogical wargames like Pacific Strategy, they’ve taken a meaningful stride toward balancing realism with simplicity, freeing students and faculty from the burdensome rulesets that too often turn education into rote procedure. This approach echoes the Prussian innovators who shifted from rigid charts and tables to expert adjudication, allowing leaders to focus on operational planning and learning from mistakes – a core tenet of effective military education that the Army has long understood but too rarely practiced.

Yet, as I read their account of this multi-year endeavor at the USAWC, I can’t help but see it through the lens of the broader reforms I’ve advocated in works like Path to Victory: America’s Army and the Revolution in Human Affairs and Adopting Mission Command. The real revolution we need isn’t just in how we teach campaigns in crisis and conflict; it’s in transforming the Army’s entrenched 2nd Generation Warfare (2GW) culture – that attrition-based, firepower-obsessed mindset born of World War I trenches, where centralized control and predictable processes reign supreme. This outdated paradigm, with its emphasis on massed forces and scripted outcomes, leaves us ill-equipped to maneuver in 3rd Generation Warfare (3GW) style, where speed, initiative, and decentralized decision-making turn the tide, let alone to outthink and outfight the asymmetric, non-state threats of 4th Generation Warfare (4GW). In 4GW, battles are won not just on maps but in the realms of culture, politics, and information – domains where adaptability isn’t a luxury but a survival imperative.

Spahr, Mandle, and Stinchfield’s integration of AI into Free Kriegsspiel is a promising tool for fostering this adaptability. By using LLMs to generate detailed operations and intelligence summaries, battle damage assessments, and timelines based on student inputs, they’ve reduced the “overhead” that plagues traditional wargames. Students can now iterate on plans against a simulated Chinese invasion of Taiwan, adopting red-team perspectives like the PLA’s capabilities, without getting bogged down in artificial rules. The “open then closed” prompting approach, prioritizing scenario-specific data over internet hallucinations, shows prudent human oversight – a critical safeguard against AI’s occasional flights of fancy. And the results? Universally positive, with faculty empowered to “conduct it rightly,” as the old Prussian critics once lamented.

But here’s where we must push further: These AI-assisted wargames shouldn’t be confined to classrooms as mere educational repetitions. They must become the cornerstone of officer evaluation, selection, and promotion – a radical shift from our current personnel system, which rewards careerists who excel at checking boxes and pleasing superiors rather than demonstrating true competence under uncertainty. As I’ve argued repeatedly, we need outcome-based assessments, where performance in unscripted, free-play simulations like Pacific Strategy counts heavily toward jobs, promotions, and even reliefs. Imagine annual war games where officers command in force-on-force exercises just short of live combat, their decisions adjudicated by AI-augmented experts, revealing who thrives in chaos and who clings to rigid plans. This isn’t about confirming what the brass wants to believe; it’s about exposing flaws in our doctrines and leaders.

The War Department’s historical mistake – one repeated across services – has been using wargames to seek tidy answers or validate preconceived notions, as seen in the mixed results of earlier rigid games in the China Integrated Course. True wargames, with clear winners and losers emerging from the fog of simulated war, should instead generate more questions than resolutions: Why did that multi-domain integration fail? How do we better leverage alliances in 4GW scenarios? What unanticipated tensions arise when risk meets decisiveness?

In my view, this is the “parallel evolution” we require – a holistic overhaul that aligns personnel practices with mission command principles, decentralizing authority to nurture adaptive leaders who can improvise in the face of 4GW ambiguities.

The article rightly flags challenges like information security (moving from glitchy government tools like Ask Sage to commercial LLMs like Grok) and map management, but these are solvable with closed networks and modern interfaces. More pressing is building diverse faculty teams who practice these games themselves, ensuring they’re not just adjudicators but exemplars of the 3GW mindset. Without tying these innovations to personnel reform, we risk applying a bandaid to a system riddled with the cancer of conformity and risk-aversion.

Spahr, Mandle, and Stinchfield have given us a blueprint for wargaming that honors the educational ethos captured in that 1914 Scientific American quote: not a game to win, but a forge for experience and growth through errors. Let’s seize this moment to expand it into a force multiplier for the entire Army, creating leaders ready for the unpredictable wars ahead. The path to victory demands nothing less.

Don, thanks for the thoughtful, insightful, and provocative comment. I smiled with your final sentence; you know how pivotal “Path to Victory” was in my own intellectual development. Some good news is that there is currently an effort to figure out how to incorporate that operational competence into evaluations. Of course, the devil is in the details, but at least there is the intent to do exactly what you are proposing.

In my opinion, with the nature of combat operations changing in the era of drones, we might have LLM trained models on historical data. Would an LLM model have worked to predict what Nazi Germany achieved in the invasion of France with armored forces?

I briefly looked at the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) TOE. I wonder whether helicopter operations are even possible with drones and cheap ground to air missiles? How would a LLM score such operations? Should we send Ukraine a large number of helicopters and see if they can use them? Will helicopters sit on the ground rather than venture into the combat zone?

How about a nice game of chess?

The game of chess and all its strategies are rooted in war. It’s not based on chance but on pure strategy. However, real-world scenarios are much more complicated and often follow an anything-goes approach (no rules). Since the current discussion (of the day) is solely focused on Taiwan, I wonder if AI is being forced to assume specific presuppositions and not given an opportunity to tell us how and where the next war might be fought. General Billy Mitchell warned of an attack that no one saw coming. Nothing has changed; it’s happening again today.

How about thinking about the unthinkable, for a change?

Re: “wargaming” by the U.S./the West — but only if considered pertinent and applicable — might the following prove useful to our wargaming? From the second and third to last paragraphs of the section “One of the Vanquished Gives Evidence” of the book “Strange Defeat” by Marc Blouch:

“As it was, our war, up to the very end, was a war of old men, or of theorists who were bogged down in errors engendered by the faulty teaching of history. It was saturated by the smell of decay rising from the Staff College, the offices of a peace-time General Staff, and by the barrack-square. The world belongs to those who are in love with the new. That is why our High Command, finding itself face to face with novelty, and being quite incapable of seizing its opportunities, not only experienced defeat, but like boxers who have run to fat and are thrown off their balance by the first unexpected blow, accepted it.

But our leaders would not have succumbed so easily to that spirit of apathy which wise theologians have ever held to be among the worse sins, had they merely entertained doubts of their own competence. In their hearts, they were only too ready to despair of the country they had been called upon to defend, and of the people who furnished the soldiers they commanded.”

Question — Based on the Above:

If “the world belongs to those who are in love with the new,” then — not only militarily but also politically, economically, socially and even value-wise — (a) what should be considered as “new” and (b) what should be, accordingly, considered for immediate incorporation into our wargames?

Addendum:

If such things as “fire, devotion and love,” for example, for one’s country, for where that country is going, for what that country provides for and for what that country now stands for; if this/these such “fire, devotion and love” matters are (a) the opposite of the “spirit of apathy” addressed in the quoted item provided in my initial comment above but, for various reasons, (b) are not so much present in one’s country at the present time,

Then, given Marc Bloch’s experiences, thoughts and observations — found at my initial comment above — must not this/these such “spirit of apathy” matters be incorporated into one’s present-day wargames, which are now being developed at this exact same such specific time?

Thus, if our military leaders, now or in the near future, despair of the country they have been called upon to defend, despair of the people who furnished the soldiers they command and/or despair as to other related matters, then, as these exact such matters, are they not something that, indeed, (a) are exceptionally “wargame pertinent” and, thus, (b) are matters that MUST be incorporated into one’s contemporary wargames?

(This, for example, if for no other reason than to make one’s civilian superiors aware of the consequences — or the potential consequences — of their actual, and/or proposed, actions?)

LLM is very democratized. According to the news, China is leading LLM and AI technologies. I am sure China has access to LLM just like its adversaries. What makes the U.S. think that China does not run its own simulations and figure out how to beat the Pacific strategies.