EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the eighth and final installment in a multi-part series that examines how professional military education should be designed. This and subsequent articles will look through the lens of the competencies required of officers as the global security environment changes once again. The collection of articles can be found in a collection here once they have been published.

A successful end-state approach to course design will produce an unusable first draft, one that is optimized to develop officers who are able to fight the sorts of wars that their country is preparing to fight, but which makes no concessions to the organizational realities of the teaching environment.

Over the past several weeks, War Room has featured seven articles in our series on competency development and professional military education (PME). Those articles stand on their own merits as arguments in favor of one or another approach, each of which has some degree of legitimacy in the practitioner and researcher worlds. In this final article, we aim to strengthen our case by making explicit three aspects which informed all of the previous articles. These are: 1) an “end state” approach to competency development; 2) an acknowledgement of multiple legitimate courses-of-action and centers of gravity; and 3) an implied sphere of consensus, sphere of legitimate controversy, and area of deviance. We will briefly explain each in turn before making our final case for a competency development structure.

First, let us make explicit our “end state” approach to course planning. On those rare occasions when course directors are given the responsibility to significantly revise their programs, they will typically use their existing model as a starting point and will look to more prestigious programs for inspiration. This has given rise to a “copy-paste” logic of course revision that has in turn led to Frankenstein courses that boast many sound components, but which often fit together poorly. As experienced course directors ourselves, we have struggled to find resources to guide course revision in a logical manner that connects to the deeper purpose of what we do. Lacking international guidelines and guardrails, we have instead worked backward from our local context to figure out the best end state for our nations and services. Not surprisingly, we discovered that these needs look very different from one context to another. The first lesson we gained is that we need to decouple institutional logic from competency development logics. A successful end-state approach to course design will produce an unusable first draft, one that is optimized to develop officers who are able to fight the sorts of wars that their country is preparing to fight, but which makes no concessions to the organizational realities of the teaching environment. The art of course design is then to develop a subsequent draft that is fitted to reality, with an honest assessment of how far it falls short of the ideal.

The real-ideal tension brings us to our second insight, concerning the local nature of course of action and center of gravity identification. As course directors work toward their first draft, they should keep in mind that the desired end state may be reached by various courses of action. For countries focused on fighting what Mary Kaldor called “new wars,” for example, one option may be to optimize the program in the ways described by Todd Greentree and Craig Whiteside in their article. Alternately, it may instead follow the approach described by Heather S. Gregg in her article. Likewise, a “future war” orientation may resemble the MDO approach described by Katrine Lund-Hansen and Jeff Reilly, or the technology focus described by Vicky Karyoti. Local context is everything. Planning methods can be used to help untangle these difficult judgment calls, and often an adapted center-of-gravity analysis can be particularly helpful. For example, the competency development center of gravity for one country may be the overriding requirement for its officers to be able to deploy into component commands within a joint force. In that case, a single-component approach of the sort we previously outlined may be preferred to the joint approach described by James Campbell.

The final point we want to make explicit concerns the nature of legitimacy. In civilian academic programs, course directors derive their learning objectives from the mature academic fields in which they have specialized. In PME, new and emerging focus areas are often imported from military policy arenas without the supporting academic frame.

As a result, we must derive legitimacy from a combination of the policy and practitioner worlds as well as the relatively small academic world of military studies, although this is not without its challenges. One challenge that we face is over-correction when a new and trendy concept arrives on the scene. There is also a danger that unfounded views voiced by influential figures but based on tiny samples or bureaucratic compromises may exert undue influence over a local context. To guard against these tendencies, it is helpful to visualize competency development as the outcome of a global debate about the changing character of war and the evolving body of professional military expertise, a debate that includes practitioners and researchers.

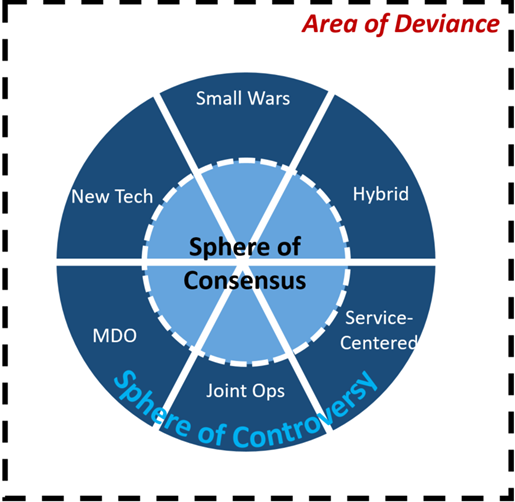

This debate can be modeled using communication scholar Daniel Hallin’s famous spheres. The inner sphere represents the sphere of consensus, where we assume we all agree on the core competencies officers need, regardless of local context. These need not be endlessly debated. All countries want officers to be effective leaders with a basic knowledge of military affairs, a basic orientation toward national strategy and global politics, and so on. Of greater interest is the sphere of legitimate controversy that surrounds the sphere of consensus. This is loosely structured, but does have structure: legitimate positions are based on compelling evidence from the world of practice, research, or both. Beyond this sphere is the large area of deviance, where heterodox views are expressed and where new ideas generally first appear.

Figure 1: The Sphere of Consensus, Sphere of Controversy, and Area of Deviance

Having made explicit the deeper logic uniting the articles in this series, we would like to conclude with two final points. First, and to repeat ourselves, NATO countries should recognize that PME is not an end in itself, but is rather the best available means to achieve competency development. It is time, in our view, for the field of PME studies to stop focusing on institutional characteristics (e.g., whether courses should be taught by civilian or military instructors), and start focusing on desired outcomes. The goal of militaries is to fight and win wars. The goal of our PME should be to develop competencies that aid nations in fighting and winning their sorts of wars.

Second, PME institutions struggle to develop appropriate competencies because we lack a Competency Development Center of Excellence or other similar structure. Such a structure could provide enormous benefits if it did just three things: clarify the sphere of consensus (what every officer needs to learn); continuously refine the contours of various courses of action within the sphere of controversy (aiding policymakers in focusing their priorities); and share best practices in developing the various competencies implied by the developed alternatives . We view this collection of articles as a call for NATO or other international organizations to develop such a structure. In the meantime, we encourage our fellow course directors to focus as much as possible on competency development, rather than the distractions that plague PME.

Thomas Crosbie is an Associate Professor of Military Operations at the Royal Danish Defence College. He is the series editor of Military Politics (Berghahn Books) and has published widely on topics including the military profession, military politics, Professional Military Education. He is currently the director of the Educating Future Warfighters Project.

Holger Lindhardtsen is a researcher at the Institute for Military Operations at the Royal Danish Defence College. He is a project member of the Educating Future Warfighters Project, focusing on competency development for future conflicts.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: L: Grant Hall located at 415 Sherman Avenue, Fort Leavenworth, KS, home of the United States Army Combined Arms Center Headquarters; R: The Lewis and Clark Center, Fort Leavenworth, KS

Photo Credit: L: Don Middleton, U.S. Army; R: Courtesy of the U.S. Army CGSC Twitter account

None of the above models takes as a focus, how do we train officers, some whom may be leaders, to devise ways, means to achieve an end which is a political objective. Both in the Korean War and in Iraq, the US Army failed to have policies and procedures to integrate replacements into units to retain operational effectiveness. We saw that with “Stop Loss Orders.” It is an unfortunate fact that more senior officers may try to promote officers to build a coalition of officers supporting the more senior officers rather than on merit. It is an unfortunate fact that women can’t cut in ground combat. Thus, they may be in stateside units getting advanced degrees and building relationships with more senior officers and bureaucrats while those in combat lack that access.

While it would be a career limiting caper, the resources above fail to reference The Heritage Foundation Project 2025. Form that,

“But this is now Barack Obama’s general officer corps. That is why Russ Vought

argues in Chapter 2 that the National Security Council “should rigorously review

all general and flag officer promotions to prioritize the core roles and responsibilities

of the military over social engineering and non-defense related matters,

including climate change, critical race theory, manufactured extremism, and other

polarizing policies that weaken our armed forces and discourage our nation’s finest

men and women from enlisting.” Ensuring that many of America’s best and brightest

continue to choose military service is essential.”

Re: such things as “competency,” did you — and the Heritage Foundation Project 2025 people — take into account that, for many young people considering joining the U.S. military today (and, specifically, “the best and the brightest” of such young people): for many of these such young people, a military whose leadership does not take into serious account such things as climate change, critical race theory, extremism, etc., this is a military that these young people (a) may not consider as “competent” and, thus, (b) may not wish to join? Herein, these such young people (again, “the best and the brightest?”) believing that such things as climate change, critical race theory, extremism, etc. — in part because they are polarizing — qualify in one way or another and at least in their minds — as (a) “defense-related matters” which (b) MUST be taken into account by any “competent” military today?

(Thus, if “ensuring that many of America’s best and brightest continue to choose military service is essential,” then [a] are we damned if we DON’T eliminate such things as climate change, critical race theory, extremism, etc., from our professional military education programs or [b] damned if we DO eliminate such things as climate change, critical race theory, extremism, etc., from our professional military education programs???)

Your efforts have not gone unnoticed. Thank you for being there for me.

From the second to last paragraph of our article above:

“Having made explicit the deeper logic uniting the articles in this series, we would like to conclude with two final points. First, and to repeat ourselves, NATO countries should recognize that PME is not an end in itself, but is rather the best available means to achieve competency development. It is time, in our view, for the field of PME studies to stop focusing on institutional characteristics (e.g., whether courses should be taught by civilian or military instructors), and start focusing on desired outcomes. The goal of militaries is to fight and win wars. The goal of our PME should be to develop competencies that aid nations in fighting and winning their sorts of wars.”

Re: “their sort of wars,” in many/most of the threads that I have commented on in this series, I have attempted to describe both (a) the “end state” that the U.S./the West — both at home and abroad — has sought to achieve post-the Old Cold War (to wit: the better organizing, ordering, orienting, etc., of the states and societies of the world [to include our own]; this, so that same might be made to better interact with, better provide for and better benefit from such things as democracy, capitalism, markets, trade, etc., and (b) the opponents (those both here at home and there abroad) who (1) would lose power, influence, control, etc., via these such transformative processes and who, accordingly, (2) would use all their instruments of power, persuasion, etc.; this, to try to prevent, and/or to roll back, same.

(From this such perspective, one can see why, post-the Old Cold War, the “transformative-driven” U.S./the West — much like the “transformative-driven” Soviets/the communists of the Old Cold War — would gain for ourselves both great power and small opponents, both state and non-state actor opponents and both in one’s own home country and abroad opponents.)

Thus, the kind of initiative (and, thus, the kind of wars) upon which we have been embarked post-the Old Cold War — and thus the kind of initiative (and, thus, the kind of wars) in which our militaries should have been made “competent” to fight and win during this time — these were/are (a) the full range of wars relating to (b) the full range of capabilities available to (c) the full range of “resisting change”/”rolling back change” opponents listed, in parenthesis, at the end of my paragraph immediately above.

Thus, if the goal of our PME should be to develop competencies that will aid nations in fighting and winning “their sort of wars,” then — from the perspective that I provide above — (a) what kind and/or “sort” of wars should be included (answer: nearly all kinds?) — and what kind and/or “sort” of wars can be excluded (are their any?) — and, thus, (b) what kind of competencies (relating specifically to the determined list of included wars) will aid NATO, etc., nations — in fighting and winning — these such wars?

Question — based on the perspective that I provide above:

In order for our great power and small opponents, our state and non-state actor opponents and our here at home and there abroad opponents (see my in parenthesis paragraph at my comment immediately above) — in order for these folks to “win” (defined as [a] the prevention of the transformation of their/our states and societies more along ultra-modern/ultra-contemporary U.S./Western political, economic, social and/or value lines and, thereby, [b] the prevention of those currently “in change” from having to give up, and/or not gain further, power, influence, control, status, privilege, prestige, safety, security, etc. based on the status quo or a suggested “golden age” status quo ante) —

In order for this diverse group of opponents to do this (to “win” — as defined by me above), does this:

a. Require that this diverse group of opponents engage — exclusively — in some form of military action against the U.S./the West and/or our partners and allies? Or:

b. Can this diverse group of opponents also “win” (again as defined by me above); this, for example, by emphasizing, championing and “weaponizing” such things as their — and indeed our — traditional social values, beliefs and institutions?

(If so, then, re: “competency,” should the professional military education of our military personnel — today and going forward — also include courses on, shall we say, THIS aspect of our current wars/conflicts?)

Dear Sir/Ma’am,

I would like to know if all eight parts of this multi-part series that examines how professional military education should be designed is available as one complete article or does it need to be downloaded separately? If separately, where are they accessible?

Samuel,

You can find all of the articles here

https://warroom.armywarcollege.edu/tag/pme-competencies/

The War Room Editorial Team

A final thought:

As relates to the kinds and/or sorts of wars that we are engaged in today, and may be engaged in in the near future, and thus as relates to the the kinds and/or sorts of competencies that we require to successfully fight and win such wars; as to these such matters, let us consider:

a. Re: “historical mindedness,” the 300 plus year period of modern capitalism and:

b. Re: “strategic empathy,” those who were, are and in the near future will be (a) threatened by same and, thus, who (b) used, are using and in the near future will use all their instruments of power and persuasion; this, in an attempt to retain — and/or to regain — the degree/the previous degree of power, influence, control, status, prestige, privilege, safety, security, etc., which was, is and in the near future will be threatened by modern capitalism.

As to these such — directly related/connected at the hip — “historically minded” and “strategic empathy” matters, consider the following:

“Capitalism is the most successful wealth-creating economic system that the world has ever known; no other system, as the distinguished economist Joseph Schumpeter pointed out, has benefited ‘the common people’ as much. Capitalism, he observed, creates wealth through advancing continuously to every higher levels of productivity and technological sophistication; this process requires that the ‘old’ be destroyed before the ‘new’ can take over. … This process of ‘creative destruction,’ to use Schumpeter’s term, produces many winners but also many losers, at least in the short term, and poses a serious threat to traditional social values, beliefs, and institutions.” (From the very first page, of the very first chapter [the Introduction chapter] of the book “The Challenge of the Global Capitalism: The World Economy in the 21st Century,” by Robert Gilpin.)

“All in all, the 1980s and 1990s (the 2000s and the 2010s also — Muller’s book is written in 2002) were a Hayekian moment, when his once untimely liberalism came to be seen as timely. The intensification of market competition, internally and within each nation, created a more innovative and dynamic brand of capitalism. That in turn gave rise to a new chorus of laments that, as we have seen, have recurred since the eighteenth century: Community was breaking down; traditional ways of life were being destroyed; identities were thrown into question; solidarity was being undermined; egoism unleashed; wealth made conspicuous amid new inequality; philistinism was triumphant.” (See the book “The Mind and the Market: Capitalism in Western Thought,” by Jerry Z. Muller, and, therein, the chapter on Friedrich Hayek.)

Question – Based on the Above:

With regard to ensuring our — and our partners and allies’ — military personnel have the requisite competencies needed to fight and win our and their nations’ wars; as to these such missions and requirements, (a) are not foundational courses, (b) addressing the “cause” and “effect” matters — the historically-minded and strategic empathy matters — that I present above, (c) as these such foundation courses required?

Correction to the final part of my comment immediately above. It should read:

(c) are not these such foundational courses required?

Apologies.

Additional Question — Related to the above:

As to the “historical minded” and “strategic empathy” matters that I present above; wherein, for the last 300-plus years the threat posed by the political, economic, social and/or value changes demanded by the champions (and enforcers) of modern capitalism have resulted in internal and external conflicts and wars with (a) both great powers and small, with (b) both state and non-state actors and with (c) both opponents here at home and there abroad (all of whom are threatened by these such changes and all of whom, accordingly, have and will use all their instruments of power and persuasion to avoid, and/or to reverse, such changes);

As to these such — amazingly important, indeed long-running and indeed explanatory over time “historically-minded” and “strategic empathy” matters — who, at our war colleges, etc., should teach foundational courses on same?