On August 1, 2008, three months after the 2008 NATO Bucharest Summit where Georgia and Ukraine received promises of future NATO membership, South Ossetian forces, backed by Moscow, began shelling Georgian villages.

The 2008 Russo-Georgian War remains critical for understanding the dynamics of modern warfare and Russia’s tactics to wage war to restore its global influence. What initially seemed to be just a localized skirmish in a distant region has become a harbinger for the challenges that define the current geopolitical landscape.

The brief but impactful five-day war, which marked Europe’s first armed confrontation of the twenty-first century, signaled Russia’s revival of Soviet-era anti-Westernism and territorial ambitions, introduced the cyber domain in warfare, and uncovered President Vladimir Putin’s tendency to strike when the West’s focus is diverted. Russia’s New Generation Warfare, the development of which is often linked to Russian Chief of Staff Valery Gerasimov’s 2013 article “The Value of Science in Prediction,” was tested first and foremost in Georgia. Before delving into these aspects, however, let’s first revisit the events of August 2008.

The Outbreak of Hostilities

On August 1, 2008, three months after the 2008 NATO Bucharest Summit, where Georgia and Ukraine received promises of future NATO membership, South Ossetian forces, backed by Moscow, began shelling Georgian villages. Despite Georgia’s unilateral ceasefire, which signaled a desire to avoid conflict, the attacks persisted, prompting Georgian forces to respond on August 7. Russian forces countered, quickly capturing disputed territories and expanding the conflict into Abkhazia, Georgia’s other breakaway region, until a ceasefire was brokered on August 13 by French President Nicolas Sarkozy.

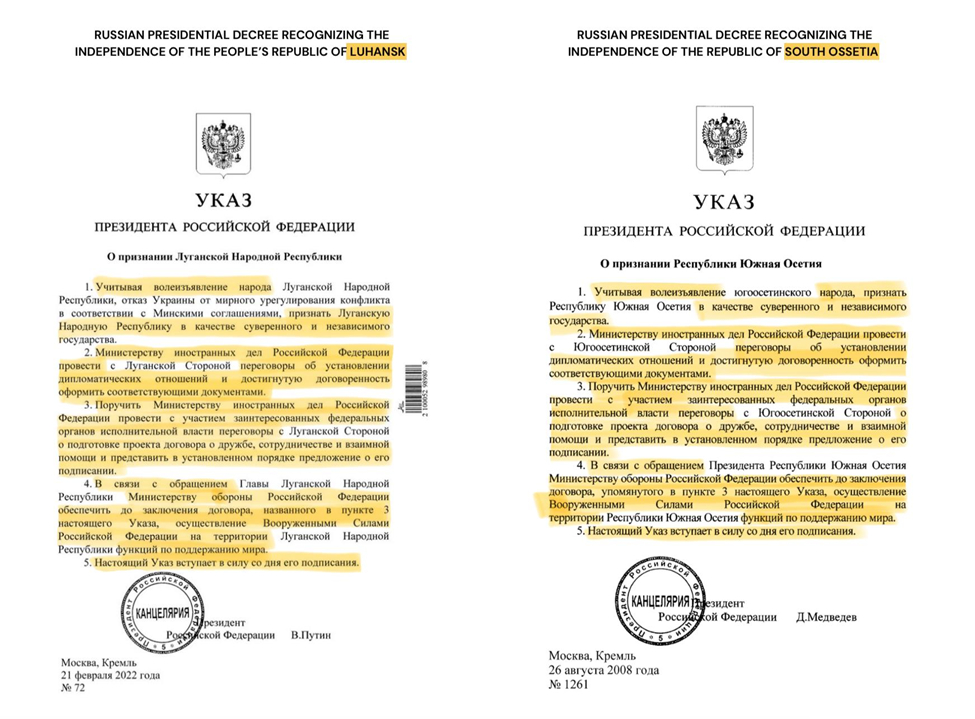

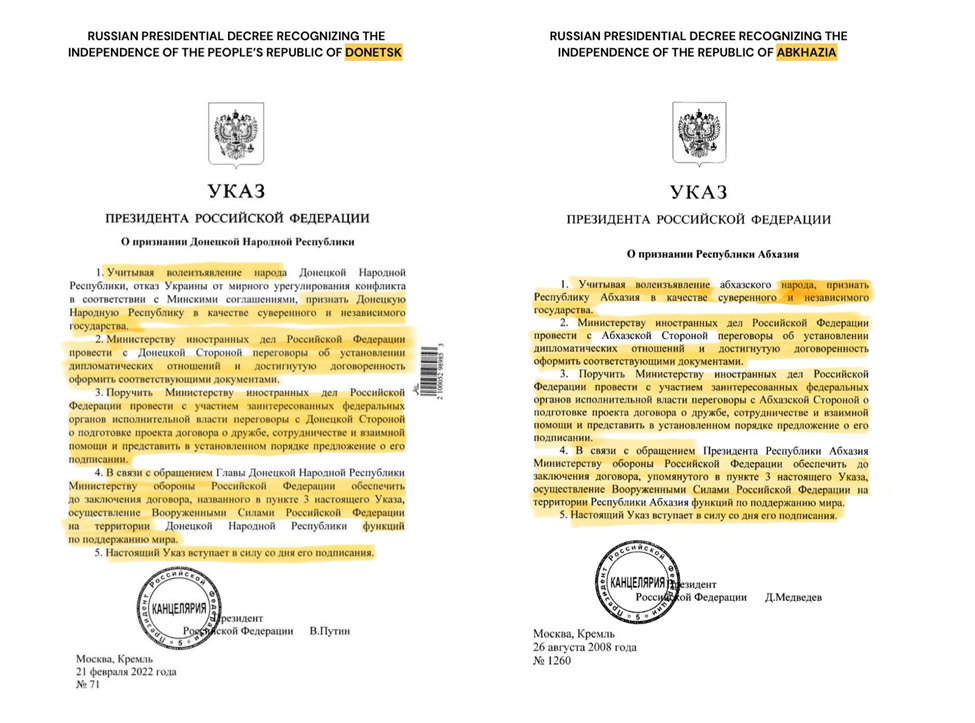

To justify the incursion, the Kremlin accused the Georgian side of committing “genocide” and “aggression” against Ossetians, an ethnic minority constituting around two-thirds of the residents of South Ossetia, an administrative enclave within Georgia’s internationally recognized borders. In the aftermath, Russia recognized Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states and occupied them in violation of the ceasefire agreement.

This move presaged Russia’s actions in 2022 when Moscow recognized Donetsk and Luhansk using verbatim the language it had employed to recognize Georgia’s breakaway regions. The conflict underscored Russia’s strategy of leveraging ethnic and separatist tensions to justify military interventions and extend its influence in the region.

New Reality, Old Russia

The 2008 war was a turning point in history that reestablished Russia as a Soviet-like imperial power that the West believed ended with the Cold War. It signaled the failure of the decade-long diplomatic nexus the West had built to appease Moscow, and came after Putin’s now famous 2005 speech in which he declared, “The collapse of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century.”That speech followed democratic revolutions in Ukraine, Georgia, and Kyrgyzstan, but Georgia and Ukraine pushed for NATO membership and became targets for Putin’s military might.

After the Iron Curtain fell, the West sought to end geopolitical divisions and foster lasting peace with Russia through various initiatives, including the Charter of Paris for a New Europe, agreements under the OSCE, NATO’s Partnership for Peace, and the NATO-Russia Council. This was a dual-track strategy aimed to integrate Eastern Europe while offering Russia closer ties with NATO and the EU. Although these efforts initially found some success, Putin’s actions in 2008 revealed his broader ambitions to restore Russia’s geopolitical influence near its borders, emulating past Tsars and Soviet leaders.

In hindsight, Putin’s dictatorial aggression should have been halted early before it metastasized. In 2008, the Georgian government believed that South Ossetia was too minor a prize and feared that Moscow’s ambitions extended far beyond it. However, this perspective was not widely shared in the West at the time. It took the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 to recognize that the Georgians were right.

As Georgia pursued a pro-Western course under President Mikheil Saakashvili, Russia realized that if countries like Georgia were allowed to democratize and join the EU and NATO, it could spark a domino effect across the region, undermining Moscow’s influence over its “near abroad.” The West, however, failed to anticipate that the reluctance to impose significant consequences on Russia in 2008 would embolden Putin to wage further wars to prevent the Westernization of former parts of the Soviet Union in the Caucasus and Eastern Europe.

The Russo-Georgian War was, indeed, a buildup to Russia’s larger-scale wars in Ukraine. The international community’s response to the war in Georgia—while quick in brokering a ceasefire—ultimately fell short in deterring future aggression. Russia had returned to its old, Cold War-like behavior, and the Western security framework was unprepared to confront renewed authoritarian aggression.

Old habits die hard, even in global politics. States with an authoritarian past should not be underestimated, even when a brief period of collaboration hints at the possibility of drastic change. The 2008 events in Georgia suggest that tolerating authoritarian aggression without imposing any punitive measures emboldens the bully. The challenge for democratic political leaders is to take punitive action without sparking a war and losing political support at home.

The Dawn of Modern Hybrid Warfare

Before the term “hybrid war” became widely recognized, the 2008 Russo-Georgian War offered an early example of cyber tactics in modern conflicts. For the first time in history alongside traditional combat, Russia launched cyberattacks targeting Georgia’s government websites, media outlets, and financial institutions, causing confusion and disrupting communication. These attacks extended the conflict into the digital domain, demonstrating how information and infrastructure could be weaponized. This shift towards cyber warfare underscored the growing importance of cybersecurity, contributing to the establishment of the U.S. Cyber Command in 2009.

Russia’s cyber operations aimed to deny, degrade, and destroy information within Georgian computer networks while gathering intelligence. The attacks included distributed denial of service attacks and website defacements, effectively shutting down key Georgian websites, including those of the president, parliament, and major banks. Hackers also used advanced techniques like SQL injections to infiltrate networks and gain access to sensitive data, further destabilizing Georgia’s response.

The Russo-Georgian War highlighted Moscow’s strategic use of cyber warfare, revealing a growing threat that continues to shape military strategies and global security challenges today.

Numerous websites were defaced with images comparing President Saakashvili to Adolf Hitler, highlighting the psychological aspect of the cyberattacks. Evidence later showed that some of Georgia’s internet traffic was routed through Russian servers, implying Russia’s direct involvement. Additionally, Russian cyber operatives manipulated online polls on CNN to influence international public opinion, framing Russia’s actions as a legitimate peacekeeping mission.

Despite Georgia’s relatively limited internet infrastructure at the time, these cyberattacks significantly aided Russia’s invasion by sowing confusion, demoralizing the Georgian government, and allowing the Kremlin to gather intelligence on Georgia during the war. The Russo-Georgian War highlighted Moscow’s strategic use of cyber warfare, revealing a growing threat that continues to shape military strategies and global security challenges today.

Russia increasingly recognized the psychological impact of warfare, shaped by elements such as information manipulation, cyber operations, ambiguous actions without clear attribution, criminal networks, and diplomatic or economic pressures, as a driving force in early 21st-century conflicts. This understanding became integral to their military doctrine, aligning with General Valery Gerasimov’s assertion that, “in the 21st century we have seen a tendency toward blurring the lines between the states of war and peace. Wars are no longer declared and, having begun, proceed according to an unfamiliar template…The role of nonmilitary means of achieving political and strategic goals has grown, and, in many cases, they have exceeded the power of force of weapons in their effectiveness…All this is supplemented by military means of a concealed character, including carrying out actions of informational conflict and the actions of special-operations forces. The open use of forces — often under the guise of peacekeeping and crisis regulation — is resorted to only at a certain stage, primarily for the achievement of final success in the conflict.”

Seizing the Right Moment to Strike

The 2008 invasion of Georgia demonstrated Putin’s strategy of launching surprise attacks when Western leaders are distracted. During the opening of the Beijing Summer Olympics, while world leaders were focused on the ceremony, Russia began bombing Georgia’s Moscow-backed separatist region of South Ossetia. This timing allowed Putin to initiate Europe’s first armed conflict of the century while key global figures, including U.S. President George W. Bush, were out of reach.

Putin sets the record for launching invasions during the Olympics, annexing Crimea in 2014 during the Sochi Winter Olympics, and launching Ukraine’s full-scale invasion after he and Xi Jinping agreed on their “no limits” partnership during the Beijing Winter Olympics. On the day of the 2024 Olympic Games opening in Paris, a coordinated sabotage of France’s national railway stranded millions of passengers, and some intelligence experts point to Russian involvement. Putin also tested arson attacks throughout Europe this summer but has not struck a new country recently. This suggests that as long as Russia remains occupied with Ukraine, the likelihood of an attack elsewhere remains low.

Putin’s history of surprise attacks goes even beyond the Olympics. Just this February, Alexei Navalny died right before the opening of the Munich Security Conference, Europe’s major security meeting that convenes with many world leaders and high-level officials in attendance.

Moscow carefully timed the move. Yuliya Navalnaya, Alexei’s wife, had just arrived in Munich to negotiate the next stage of the prisoner swap deal, which Navalny’s team had been trying to facilitate between Russia and the West. Christo Grozev, an Oscar-winning investigative journalist for his documentary Navalny, devised a plan with Maria Pevchikh, Chairwoman of Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, to free several political leaders from Russian prisons in exchange for Russian spies kept in custody in several countries like the United States, Germany, Norway, and Poland.

Navalny was supposed to be swapped for Vadim Krasikov, who was serving a life sentence in Germany for killing Zelimkhan ‘Tornike’ Khangoshvili, a 40-year-old Georgian citizen of Chechen descent in 2019. But after Navalny was out of the picture, early this August, Krasikov was exchanged for Evan Gershkovich, the Wall Street Journal’s Russia correspondent charged with espionage by Moscow.

On July 7, 2024, Russians attacked a children’s hospital in Ukraine a day before the opening of NATO’s 75th-anniversary summit. It did not appear to be a coincidence or a random strike from Putin’s repertoire of war crimes. He was flexing his muscles, demonstrating power, and seeking to unsettle the leaders celebrating the most effective military alliance in history.

Putin wants Western leaders on edge. He strikes when they convene to devise plans against him and invades countries when the world is saturated with national pride, cheering for their Olympic teams. From the 2008 war to the July 7 assault, Putin has sent many grim and strategic messages to prey on global leaders’ minds, dominate the geopolitical agenda, and remind the West that their collective Russia problem can get worse.

Lessons from a “Little War”

“A little war that shook the world,” as the late U.S. diplomat Ronald Asmus called it, was a turning point in history, revealing that the West was overly optimistic about cooperation with Russia and unprepared to confront Moscow’s growing ambitions to regain its power.

Sixteen years later, Russia continues to wage more significant wars, cyberwarfare poses an ever-growing threat in the era of technological innovation, and Putin continues to catch Western leaders off guard with his calculated and deadly attacks.

The events of 2008 make it clear that the consequences of underestimating authoritarian regimes are dire. What was once difficult to discern when Russia’s post-Cold War ambitions were still nascent is now undeniable—authoritarians must be taken seriously and confronted early to prevent their aggression from escalating.

Ketevan Chincharadze is a Research Intern at the U.S. Army War College and a Foreign Policy Analyst and Researcher.

Larry P. Goodson is Professor of Middle East Studies at the U.S. Army War College and author of the best-selling Afghanistan’s Endless War (2001).

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Georgian soldiers during Russo-Georgian War, 9 August 2008

Photo Credit: Giorgi Abdaladze via the Communications Division of the Administration of the President of Georgia

Here is the third paragraph under the major section heading “New Reality, Old Russia” in our article above:

“As Georgia pursued a pro-Western course under President Mikheil Saakashvili, Russia realized that if countries like Georgia were allowed to democratize and join the EU and NATO, it could spark a domino effect across the region, undermining Moscow’s influence over its ‘near abroad.’ The West, however, failed to anticipate that the reluctance to impose significant consequences on Russia in 2008 would embolden Putin to wage further wars to prevent the Westernization of former parts of the Soviet Union in the Caucasus and Eastern Europe.”

Question — Relating to the Above:

Does the above suggest to you that such things as “authoritarianism,” “revanchism,” “imperialism,” etc., were/are the motivation for Russia’s actions in Georgia, the Ukraine, etc.? And/or that Russia’s use of “hybrid warfare,” etc., in these such regions, should be seen primarily — or only — from those points of view?

Or, in sharp contrast, does the above suggest to you that — much as in the Old Cold War of yesterday and re: America’s concern with the spread of communism in our hemisphere/in our spheres of influence back then — likewise in the New/Reverse Cold War of today and re: Russia’s concern with the spread of Westernization in their hemisphere/in their spheres of influence recently — in both such cases — THESE were/are the “fears” that drove/drive intervention, and the use of such things as hybrid warfare, by the “containment” parties concerned? (To wit: by the U.S./the West in the Old Cold War of yesterday, and Russia, et. al, in the New/Reverse Cold War of today?) In this regard, consider the following two items:

“In the information age, a state of terror such as the one that Putin’s Russia has become, cannot countenance states of consent, especially next door. It is Ukraine’s constitutional order — with its independent (though still troubled) judicial system, freedom of the press, multiparty politics, largely legitimate elections, vibrant civil society, and general respect for human rights — that Putin cannot tolerate, lest it provide too tempting an example for democratic activists in his own country who have vehemently opposed him at great risk to their lives and to the public in general that shares so many ties to the people in Ukraine. The “peaceful coexistence” of the Cold War is, in this respect, not acceptable to Putin.” (See the Just Security article “Putin’s Real Fear: Ukraine’s Constitutional Order, by Philip Bobbitt.)

“As true as this rings, there is enough rhyme in recent history to remind us that it was not always so. The last time Russia and the United States grappled indirectly as adversaries in “the gray areas” during the final phase of the Cold War, it was the United States that put a hybrid “blend of military, economic, diplomatic, criminal, and informational means” to effective use, notably in Central America. Of course, there were important differences between the character of that confrontation and today, but much about the goals and the means were comparable, only it was the United States that seemed to “have it down.” (See the War on the Rocks article “America Did Hybrid Warfare Too by Todd Greentree.)

Thus, from this such perspective, who could/should be considered the “aggressor” (because their efforts to spread communism more throughout the world clearly threatened many other countries?) during the Old Cold War of yesterday? And who could/should be considered the aggressor (because our efforts to spread Westernization more throughout the world clearly threatens many other countries?) in the post-Cold War/in the New/Reverse Cold War of today?

Correction:

My first/my initial quoted item, in my comment immediately above, this can be found — not aat the third — but rather at the fourth paragraph — of the major section heading “New Reality, Old Russia” in our article above. Apologies.

Based on the information that I provide in my comments here, should we suggest a change in the concluding paragraph of our article above, for example,

From: “The events of 2008 make it clear that the consequences of underestimating authoritarian regimes are dire. What was once difficult to discern when Russia’s post-Cold War ambitions were still nascent is now undeniable—authoritarians must be taken seriously and confronted early to prevent their aggression from escalating.”

To: “The events of 2008 (etc.) make it clear that the consequences of underestimating “containment” and/or “roll back”-focused entities are dire. What was once difficult to discern when Russia’s (et. al’s) post-Cold War ambitions were still nascent is now undeniable — “containment” and “roll back”-focused entities, such as in Russia, China, etc., in the Old Cold War of today — and/or in the U.S. in the Old Cold War of yesterday — these such “containment” and “roll back” folks must be taken seriously, and confronted early to prevent their containment and roll back efforts from (a) being successful and/or (b) escalating.”

Trump screwed all that up by kidnapping Maduro an threating Greenland. He is looking just like Putin. Just because we’re America, doesn’t mean that whatever we do is right. We like to play the worlds police. An we’ve taken alot of punishment for it.