As G.K. Chesterton wisely observed, “The true soldier fights not because he hates what is in front of him, but because he loves what is behind him.”

“Task” and “purpose” are two of the most foundational doctrinal terms in the U.S. military, yet it seems that while tasks are usually clearly articulated, purposes are often treated as an afterthought or neglected altogether. But purposes provide the moral foundation from which all military action is derived and are therefore critical to success in war. As G.K. Chesterton wisely observed, “The true soldier fights not because he hates what is in front of him, but because he loves what is behind him.” However, if servicemembers are never taught what is loveable about that for which they fight then there should be no surprise if they fail to fight well. This is especially true for a nation with such a rich heritage of national purpose as the United States, founded as it is on sacred truths. Leaders should seize every opportunity to reinforce these truths that constitute America’s national purpose.

When George Washington, who intimately understood this connection between purpose and what J. F. C. Fuller called “the moral sphere of war,” assumed command of the Continental Army, he did so because of he genuinely believed in “the glorious Cause.” This commitment to the cause or purpose, in modern English vernacular, would become the driving force behind his tenacity, endurance, and leadership style. Washington knew that soldiers would endure the hardships of war only if they were given a clearly defined and objectively good purpose. They deserved a cause worth suffering for.

Five months after he assumed command, Washington reiterated the centrality of purpose to an effective fighting force, when he counseled a newly commissioned colonel to “impress upon the mind of every man, from the first to the lowest, the importance of the Cause, and what it is they are contending for.” A commander-in-chief with less appreciation for the moral sphere of war would have confined his concern for subordinates’ understanding of national purpose to key leaders. But Washington understood the power of a well-articulated national purpose to inform and influence behavior at all levels, including the tactical.

While national purpose may have little or no effect on tactical decisions such as whether to seize hill “X” or “Y,” Washington did not doubt its ability to instill courage in the hearts and minds of each soldier, regardless of rank. The moral assumptions embedded in that purpose, which in turn shaped his army’s organizational culture and standards of behavior, acted as a lens through which soldiers were to view the conflict and the character of the new nation. It did not specify tasks but reinforced the collective will of the Army to endure until it achieved a satisfactory outcome.

A year after he assumed command, the Continental Congress gave Washington the perfect tool for articulating that cause to his soldiers in the form of the Declaration of Independence. The Declaration grounded the Americans’ fight for liberty in universal truths, applicable to all peoples at all times and in all places. Armed with ultimate purpose, articulated and approved by the ruling body of the land, Washington ordered that the document be read aloud to his army in the hopes that it would clarify the great national end for which his soldiers sacrificed and inspire them to fight courageously.

The Power of Purpose

Purpose is a powerful force bordering on the transcendent. It puts steel in one’s spine and acts as an antidote to suffering. Purpose makes warriors out of cowards and patriots out of pacifists. It directs the aimless, and with such certitude comes a quiet peace and confident humility. “Courage,” Walter Grady observes, “requires the support of a purpose.”

Purpose plays a similar role in the success of organizations, armies, and nations. Napoleon’s famous observation that “in war the moral is to the physical as three is to one” encourages the warfighter to prioritize purpose as a key element of combat power. Napoleon was far from saying that the physical does not matter, but capability and capacity mean little unless there is a will to use them. That will is forged through understanding and acting according to a worthwhile purpose.

When Washington assumed command, his great challenge was to galvanize disparate state militias around a national purpose and to direct their individual and unit-level actions toward national victory rather than defense of their individual states. He did not eschew soldiers’ natural instincts to fight for self-preservation, camaraderie, and glory, but he subsumed those instincts into a collective will to endure for the sake of the country as a whole. He used the words and principles of the Declaration of Independence to do so.

Washington and Lincoln’s articulation of national purpose informed soldiers’ relationships to what Grady refers to as “absolutes,” which are the foundational moral reasons for fighting.

Purpose Still Matters

The use of the Declaration of Independence to direct the U.S. military to national ends did not end with Washington. Abraham Lincoln inherited this conviction and applied it to his particular circumstances. President-elect Lincoln hoped that the Union might still be saved upon the basis of a shared understanding of liberty as expressed in the Declaration. A couple of bloody years later, he reminded the country and its soldiers that their purpose was to preserve a nation “conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

Washington and Lincoln’s articulation of national purpose informed soldiers’ relationships to what Grady refers to as “absolutes,” which are the foundational moral reasons for fighting. It cultivated a sense among soldiers that they were no longer responsible only for their own survival and that of their families, but also for the very soul of the country. Major Sullivan Ballou, a Union officer killed at the First Battle of Bull Run, exhibited this understanding in his last letter to his wife:

I have no misgivings about, or lack of confidence in, the cause in which I am engaged, and my courage does not halt or falter. I know how strongly American civilization now leans upon the triumph of government, and how great a debt we owe to those who went before us through the blood and suffering of the Revolution, and I am willing…to lay down all my joys in this life to help maintain this government, and to pay that debt.

When America asks her sons and daughters to fight, bleed, and die, she should always provide such a clear and worthy purpose.

Rediscovering Purpose

Two hundred and forty-seven years after Washington assumed command, General Mark A. Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, admonished the graduating class of the United States Military Academy that they must be prepared to “make the right moral and ethical choices, along with the right tactical choice in the most emotionally charged environment you will ever face.” They must demonstrate “the willingness to disobey specific orders to achieve the intended purpose” and “to take risks to meet the intent.” But when leaders make these demands they must also work to furnish the moral framework within which decisions are to be made. Whether morality is objective or subjective, socially constructed and relative or universal and timeless, it has a direct bearing on how those young leaders will make ethical decisions under intense pressure.

It may be argued that such grand philosophical and moral ideas are the purview of statesmen and generals and that junior officers and enlisted need not be concerned with such matters. But according to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, this generation of servicemembers will see small elements separated from higher echelons by vast distances in which the senior-ranking officer is a lieutenant. Unlike previous great power wars, in which general officers maintained close and direct control of their formations, command and control on the future battlefield will place a high premium on autonomy and, consequently, on trust, integrity, and moral reasoning. There is no question that these servicemembers require a deep understanding of a sound overarching purpose, grounded in immutable moral principles. Just as Washington did for his army, today’s military leaders must do everything in their power to provide such a purpose.

Conclusion

In his 2012 study on the use of foundational American documents for moral education, Chaplain Ryan Rupe set out to determine if it was still feasible and effective to use the Declaration of Independence as a means for teaching virtue ethics, just as it had been for Washington and Lincoln. Chaplain Rupe gave a block of instruction centering on the Declaration to fifty Coast Guard officers, enlisted, and civilians. He concluded from the feedback he received that the meaning and principles of the Declaration still resonate in the consciences of servicemembers when they are exposed to it. However, occasional blocks of instruction are not enough to translate national principles into moral imperatives that drive behavior. This requires constant and intentional engagement from leaders at all echelons.

To that end, leaders should seize every opportunity to reinforce the sacred truths that constitute America’s national purpose. Every equal opportunity briefing is a chance to explain that all people are created equal and therefore possess an inherent right to fair treatment. Every sexual harassment and assault prevention presentation is a chance to remind servicemembers that everyone possesses the right to pursue meaningful happiness and that sexual aggression is the grossest infringement on that right. Every safety brief, change-of-command ceremony, and graduation is a golden opportunity to refocus on those principles for the support of which we pledge “our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor.”

Andrew J. Bibb is a strategic plans and policy officer in the Army Office of Business Transformation who has deployed to Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, the Arabian Peninsula, and Latvia. His work has been published in respected outlets including the Modern War Institute at West Point, Small Wars Journal, 19FortyFive, and the U.S. Congressional Record.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

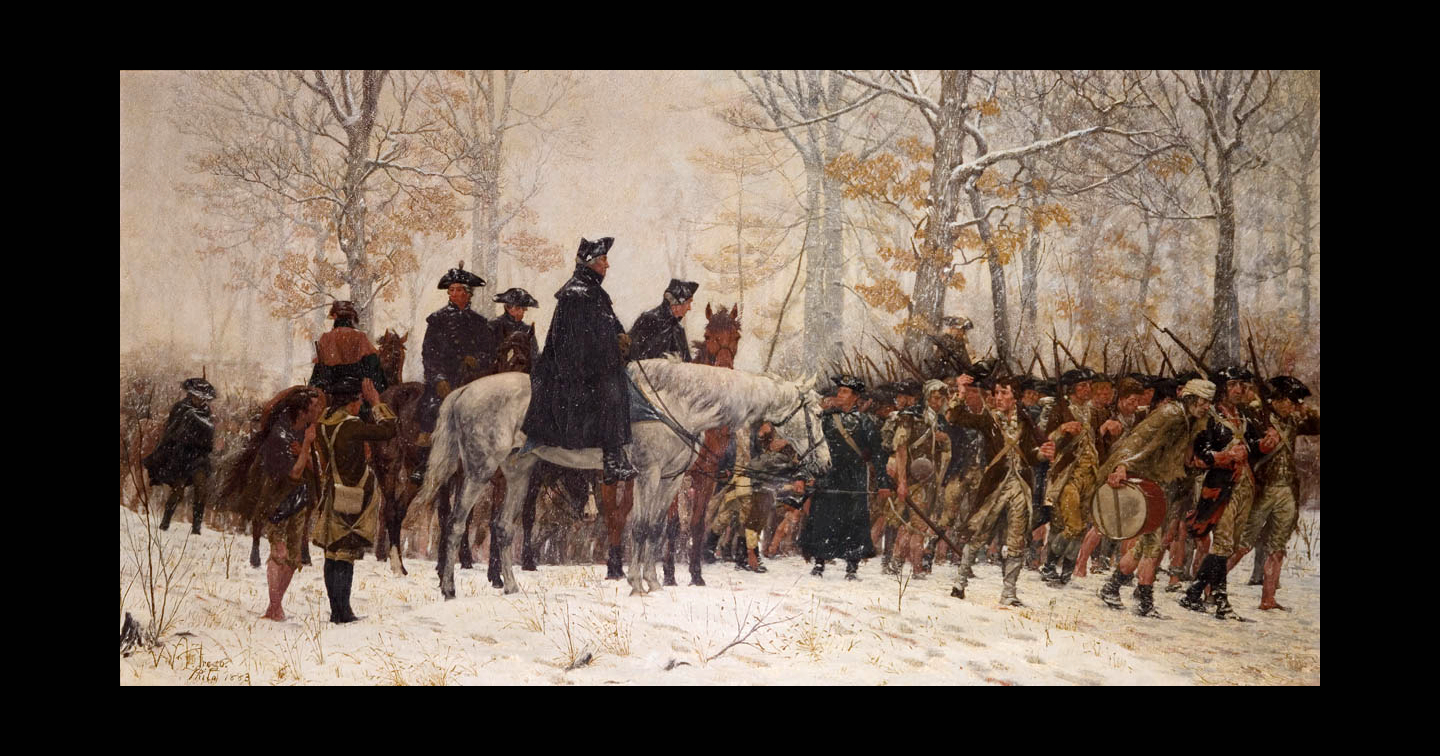

Photo Description: Painted by William B.T. Trego

Photo Credit: George Washington leading the Continental Army to Valley Forge in 1777.

From our article above: “As G.K. Chesterton wisely observed, ‘The true soldier fights not because he hates what is in front of him, but because he loves what is behind him.’ ”

Arguably, what “was behind” the soldiers of the U.S./the West in the Old Cold War of yesterday, this was the U.S./the West’s unique way of life, our unique way of governance, our unique values, etc. These such matters being clearly threatened by the revolutionary-based/”achieve revolutionary change both at home and abroad”/ expansionist tendencies of the Soviets/the communists back then. (Thus, our “containment” — and later our “roll back” — strategies.)

“The main element of any United States policy toward the Soviet Union must be that of a long-term patient but firm and vigilant containment of Russian expansive tendencies.” (See George Kennan’s “Long Telegram.”)

Arguably, what “is behind” the soldiers — of such entities as Russia, China, Iran, N. Korea, and the Islamists, etc., in the New/Reverse Cold War of today — this is THEIR unique ways of life, THEIR unique ways of governance, THEIR values, etc. These such matters being clearly threatened — post-the Old Cold War and continuing unto today — by the U.S./the West’s post-Cold War revolutionary-based/ “achieve capitalist, globalization and global economy change both at home and abroad”/expansionist tendencies.

“The successor to a doctrine of containment must be a strategy of enlargement, enlargement of the world’s free community of market democracies,’ Mr. Lake said in a speech at the School of Advanced International Studies of the Johns Hopkins University.”

(See the September 22, 1993 New York Times article “U.S. Vision of Foreign Policy Reversed” by Thomas L. Friedman.)

Thus when we look, today, to such entities as Russia, China, Iran, N. Korea, the Islamists, etc. (and even to certain conservative elements here in the U.S./the West itself?) adopting “containment” and “roll back” strategies of their own; when we see this, then what we must come to understand is that (a) “what is behind” the “soldiers” of these such diverse entities, this is (b) the perceived threat to THEIR unique ways of life, to THEIR unique ways of governance, to THEIR unique values, etc.

Bottom Line Thought — Based on the Above:

Given the “achieve revolutionary change both at home and abroad” political objective of both the Soviets/the Communists in the Old Cold War of yesterday and the U.S./the West in the New/Reverse Cold War of today; given these such matters, then (a) the only motivational tool available to the leaders of soldiers of both such groups, these must be (b) “what is in front of them” motivational tools.

From this such “revolutionary”/”what is in front of them” perspective, thus, to properly see and understand (a) motivation of American soldiers in the American Revolutionary War, (b) motivation of Soviet/communists soldiers in the Old Cold War of yesterday and (c) the motivation of U.S./Western soldiers in the New/Reverse Cold War of today?

(Note that, from the perspective that I provide here, efforts by U.S./Western leadership — to achieve such things as greater diversity, equality and inclusion today — these are seen by many/most of our soldiers [a] not through a “this is and always has been the status quo” lens [this might have been the goal, but the reality has, obviously, always been vastly different] but, rather, [b] more through a more accurate and correct “let’s achieve revolutionary change” lens? [Thus, again, a “revolutionary change”/”what is in front of them” motivational tool is what is necessary?])

Addendum:

Should you believe that “achieving revolutionary change both at home and abroad” has not been the political objective of the U.S./the West post-the Old Cold War, then consider the following:

a. At home (one quoted item):

“Liberal democratic societies have, in the past few decades, undergone a series of revolutionary changes in their social and political life, which are not to the taste of all their citizens. For many of those, who might be called social conservatives, Russia has become a more agreeable society, at least in principle, than those they live in. Communist Westerners used to speak of the Soviet Union as the pioneer society of a brighter future for all. Now, the rightwing nationalists of Europe and North America admire Russia and its leader for cleaving to the past.”

(See “The American Interest” article “The Reality of Russian Soft Power” by John Lloyd and Daria Litinova.)

b. Abroad (two quoted items):

“Politically, in many cases today, the counter-insurgent (the U.S./the West and its partner governments) represents revolutionary change, while the insurgent fights to preserve the status quo of ungoverned spaces, or to repel an occupier – a political relationship opposite to that envisaged in classical counter-insurgency. Pakistan’s campaign in Waziristan since 2003 exemplifies this. The enemy includes al-Qaeda-linked extremists and Taliban, but also local tribesmen fighting to preserve their traditional culture against twenty-first-century encroachment. The problem of weaning these fighters away from extremist sponsors, while simultaneously supporting modernisation, does somewhat resemble pacification in traditional counter-insurgency. But it also echoes colonial campaigns, and includes entirely new elements arising from the effects of globalisation.”

(Item in parenthesis above is mine. See David Kilcullen’s “Counterinsurgency Redux.”)

“Dhofar, El Savador and the Philippines are all campaigns driven by fundamentally conservative concerns. When we are looking to Syria right now, (however,) it is not just about maintaining order or even the regime, but about larger political change. In Afghanistan and Iraq too, we represented revolutionary change. So, perhaps we should read Mao and Che Guevara instead of Thompson in order to find the appropriate lessons of how to achieve large-scale societal change through limited means? That is what we are after, in the end. And in this coming era, where we are pivoting away from large-scale interventions and state-building projects, but not from our fairly grand political ambitions, it may be worth exploring how insurgents do more with little; how they approach irregular warfare, and reach their objectives indirectly.”

(Item in parenthesis above is mine. See the Small Wars Journal article “Learning From Today’s Crisis of Counterinsurgency” — an interview by Octavian Manea of Dr. David H. Ucko and Dr. Robert Egnell.)

Bottom Line Question — Based on the Above:

In each of the three examples that I provide above, the “insurgents”/the more conservative elements of these states and societies, these folks would appear to be motivated by and fighting for “what is behind them” (to wit: the status quo — or a status quo ante; this latter, if too much unwanted change is thought to have already taken place),

In circumstances such as these, can U.S./Western soldiers — and/or foreign soldiers that our soldiers will be working with — also be motivated by “you are fighting for what is behind you” suggestions?

In my explanations above, the U.S./the West, post-the Old Cold War, adopted an “achieve revolutionary change both at home and abroad” political objective; this, in the name of such things as capitalism, globalization and the global economy. This in turn:

a. Threated and alienated the more conservative elements of the states and societies of the world (to include these such elements in the U.S./the West itself) and

b. Caused them to seek support from the U.S./the West’s enemies. (For example, Russia, see item “a” in my second comment above).

Thought: From a capitalism, globalization and global economy point of view, this would seem to be very old (since at least the dawn of modern capitalism in the eighteenth century?) and recurring (happened again 100 years ago?) story. As to these two such suggestions, consider the two quoted items provided below:

“All in all, the 1980s and 1990s (and the 2000s and the 2010s also, Muller’s book is written in 2002) were a Hayekian moment, when his once untimely liberalism came to be seen as timely. The intensification of market competition, internally and within each nation, created a more innovative and dynamic brand of capitalism. That in turn gave rise to a new chorus of laments that, as we have seen, have recurred since the eighteenth century: Community was breaking down; traditional ways of life were being destroyed; identities were thrown into question; solidarity was being undermined; egoism unleashed; wealth made conspicuous amid new inequality; philistinism was triumphant.”

(From the book “The Mind and the Market: Capitalism in Western Thought” by Jerry Z. Muller; therein, look to the section on Friedrich Hayek)

“In this new world disorder, the power of identity politics can no longer be denied. Western elites believed that in the twenty-first century, cosmopolitanism and globalism would triumph over atavism and tribal loyalties. They failed to understand the deep roots of identity politics in the human psyche and the necessity for those roots to find political expression in both foreign and domestic policy arenas. And they failed to understand that the very forces of economic and social development that cosmopolitanism and globalization fostered would generate turbulence and eventually resistance, as ‘Gemeinschaft’ (community) fought back against the onrushing ‘Gesellschaft’ (market society), in the classic terms sociologists favored a century ago.”

(See the Mar-Apr 2017 edition of “Foreign Affairs” and, therein, the article by Walter Russell Mead entitled “The Jacksonian Revolt: American Populism and the Liberal Order.”)

Conclusion and related question:

As we can see from the above, the U.S./the West has over three hundred years of experience in fighting wars designed to “achieve revolutionary change both at home and abroad;” this, in the name of such things as capitalism, globalization and the global economy. Thus, the U.S./the West has over three hundred years of experience in fighting wars against “enemies” — both at home and abroad — whose soldiers were motivated by “what was behind them” (to wit: their traditional values, beliefs, etc.).

Given this such over three hundred years of experience, what can we say was used to motivate U.S./the Western soldiers — back then and again today — to overcome and defeat these such — “fighting for what’s behind them” — foes?

My final question above possibly stated another way:

If, as discussed in my comment immediately above, “community” (throughout the world and even here in the U.S./the West) has — perpetually and never-endingly — been at loggerheads with “market society” for over three hundred years. (“Forever wars” anyone?) And:

If the “soldiers” of “community” have always fought (and always ultimately in vein?) for “what was behind them:”

“Jacksonians drew their support from Northern laborers and yeoman farmers in the South and in the West. These groups, which Jackson dubbed the ‘bone and sinew of America,’ worried that the market economy would force them into the dependent class. The Jacksonians told the farmers and the laborers that they would do everything in their power to prevent this from taking place. In essence, the men and their rank and file voting allies, along with Jackson, fought a rear-guard action against encroaching industrialization and market economy. Although they won the pivotal battles, they lost the war, because their notion of a pre-capitalist agrarian society succumbed to the industrial economy after the Civil War.”

(See the ‘Encyclopedia of U.S. Political History’ by Andrew Robertson, et al., and the section therein entitled ‘Jacksonian Democracy,’ Page 194.)”

Then what did the “soldiers” of “market society” always fight for — and always ultimately win with?

(The national security requirement to [a] embrace capitalism, globalization and global economy-required “change” — or [b] “lose” to those who do this much more quickly and much more thoroughly than you did?)

In my final thought (in parenthesis) at my comment immediately above, I suggested that (a) what the soldiers of market society fight for, this was/is (b) the national security requirement to — perpetually it would seem — embrace market-demanded change.

Re: a contemporary, post-Cold War view of this such suggestion, let’s consider the following from the Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law paper “Moral Communities or a Market State: The Supreme Court’s Vision of the Police Power in the Age of Globalization” by Antonio F. Perez and Robert J. Delahunty:

a. First, let’s look at the perceived post-Cold War national security rationale for embracing market-demanded change:

” … The chief thesis of this article is that the (U.S.) Supreme Court has embarked on a program of reshaping constitutional doctrine so as to encourage and facilitate the emergence of a fully developed Market State in this polity, with a view to positioning the United States to be successful in meeting the competitive challenges of a new, post-Cold War international order. … Proponents of this vision of a globalized economy characterize the United States as ‘a giant corporation locked in a fierce competitive struggle with other nations for economic survival,’ so that ‘the central task of the federal government’ is ‘to increase the international competitiveness of the American economy.”

(Item in parenthesis above is mine. See the only full paragraph on Page 643 of the Catholic University of America paper that I reference above.)

b. Next, let’s see if we can find a — corresponding to national security and market-demanded change — “embrace diversity, equity and inclusion” suggestion:

” … This apparently inescapable tension between democracy and markets can exist, not only in developing nations, but also in the United States. Left to its own devices and without some from of governmental intervention, American capitalism seems likely to continue to favor and reward certain identifiable ethnic and racial groups disproportionately and to disfavor other identifiable groups. Particularly given the sources of much of this inequality in the nation’s history of slavery and discrimination, the persistence (and possible aggravation) of such differences would tend to create sharp and destabilizing conflicts within the American polity. American economic, political, and military elites have a clear interest in abating or suppressing such conflicts. Indeed, they must do so if the American Market State is to remain competitive in the international arena.”

(See the paragraph beginning with “At the same time, the “Grutter” Court did not disclose what conceivably was, from a purely instrumentalist perspective, the full weight of its thought;” this, at the bottom of Page 701 of the Catholic University of America paper that I reference above.)

Bottom Line Questions — Based on the Above:

Thus do we now have before us:

a. A/the reason why U.S./Western “market society” soldiers fight? (For national security reasons — as discussed in item “a” of this comment above?) And:

b. The reason why those responsible for U.S./Western national security (see “American economic, political, and military elites” at my item “b” of this comment above) see the — corresponding — national security requirement — to embrace such things as diversity, equity and inclusion?

Final question — based on final quoted item that I provide in my comment immediately above:

If “American economic, political, and military elites have a clear interest in abating or suppressing” “differences (which) would tend to create sharp and destabilizing conflicts within the American polity,”

Then how — exactly — can American economic, political, and military elites do this; this, while likewise embracing and promoting — for national security reasons — such things as “diversity, equity and inclusion?” (A process which, indeed, has tended to CREATE — and/or to AGGRAVATE — sharp and destabilizing conflicts within the American polity?)

Thus, national security “damned if you do?”/national security “damned if you don’t?

As I conclude my comments here, let me turn to this statement — from the first paragraph of Joseph Schumpeter’s 1919 “State Imperialism and Capitalism:”

“Where the cultural backwardness of a region makes normal economic intercourse dependent on colonization, it does not matter, assuming free trade, which of the ‘civilized’ nations undertakes the task of colonization.”

As this quote might indicate, soldiers of U.S./Western states and societies back then; these soldiers — along with the colonial process in general — fought to overcome the “cultural backwardness” problems of other states and societies.

Why, exactly, would U.S./Western soldiers/colonists do this? Because these such “cultural backwardness” problems (those both within their own home countries and, indeed, those elsewhere/abroad), these tended to stand directly in the way of “normal economic intercourse” (optimal capitalism and trade) and thus tended to limit/withhold the revenues needed for a nation’s national security.

Here — from our very own Joint Publication 3-22, Foreign Internal Defense (therein, see Chapter II, “Internal Defense and Development Program” and Paragraph 2, “Construct”) — appears to be a modern-day version of this such understanding. (Herein, note that the term “development,” over time, seems to have been substituted for the term “normal economic intercourse?”):

“a. An IDAD program integrates security force and civilian actions into a coherent, comprehensive effort. Security force actions provide a level of internal security that permits and supports growth through balanced development. This development requires change to meet the needs of vulnerable groups of people. This change may, in turn, promote unrest in the society. The strategy, therefore, includes measures to maintain conditions under which orderly development can take place.”

Again, and as I have discussed in certain of my other comments above, we find U.S./Western soldiers — yesterday and still today — fighting to overcome the “cultural backwardness” problems of both their own states and societies (for example, via their example?) and those such problems of other states and societies also (for example, via security force assistance?).

The (moral?) reason for doing this — yesterday as today — this would seem to be to (a) provide that optimal capitalism and trade might flourish and, thereby, (b) our and our partner nations’ national security.

As to these such (moral?) thoughts, consider the following from (a) NSC-68 and, therein, (b) Section II: “Fundamental Purpose of the United States:”

“The fundamental purpose of the United States is laid down in the Preamble to the Constitution: ‘. . . to form a more perfect Union, establish justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.”

Conclusion:

As we might see and understand from the statement immediately above, it takes MONEY to “form a more perfect Union,” to “establish justice,” most certainly to “insure domestic Tranquility and to “provide for the common defense,” to “promote the general Welfare, and to “secure the Blessing of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.”

Thus, the “moral” reason for sending our soldiers out into the world? This is provide for a world that is organized, ordered and oriented; this, so that this such world might (a) provide the U.S. with the revenues needed; this, so as to (b) meet the national security requirements noted at NSC-68 and at our Constitution above?