I wish sometimes I could go back to my own year in the War College. It was the one year that was set aside completely for the study of our profession.

— Dwight D. Eisenhower

In August 1966 as the former President addressed the U.S. Army War College (USAWC), he mused on the value of professional military education (PME) in developing senior and strategic leaders. Ironically, as the Chief of Staff of the Army (CSA) twenty years earlier, General Eisenhower approved not reopening the USAWC in favor of creating the National War College (National). Flush from victory in World War II, Eisenhower and the Army embraced a joint school to fulfill PME. Yet within a few years, the Army’s senior leadership had serious misgivings and approved resurrection of the USAWC. This article examines the Army’s post-war education framework and makes the case that it provides the means to address PME shortcomings in today’s joint force and will improve cohesion and interoperability across the Department of Defense (DoD), interagency, and allies and partners in an uncertain future.

Pre-War Senior Service Colleges and Joint Education

Prior to World War II, U.S. military officers attended senior service college (SSC) at the USAWC (then located in Washington, D.C.), the Naval War College (NWC) in Newport, Rhode Island, or Army Industrial College, which was also in the capital. A few officers, such as Eisenhower and Admiral William Halsey, graduated from more than one war college. Although no formal joint PME (JPME) requirements existed, the colleges were staffed with instructors and students from other services. Officers from the Army, Navy and Marine Corps leveraged knowledge, skills, and competencies developed through senior PME to operate at the strategic level. General George C. Marshall, as CSA, considered PME “a huge dividend” for generating an appreciation for strategic issues facing the nation and helping these officers negotiate at the highest levels during the next world war.

World War II and the Need for Joint Education

Due to the start of World War II in September 1939, the War Department suspended operations of the USAWC in the summer of 1940, while in contrast, the Navy maintained operations as the war expanded on 7 December 1941. The planning and execution of global operations identified gaps in officer PME and joint education within the first year of the U.S. entry into the war. The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) addressed this requirement for command and staff of joint operations on the land, sea, and air through the establishment of the Army-Navy Staff College (known as ANSCOL) in June 1943, which provided a 21-week course at the former USAWC facilities at Washington Barracks (later renamed Fort Lesley J. McNair), as well as at Newport, Fort Leavenworth, and other locations. Throughout the war, twelve cohort classes met consisting of officers from the services and allies, as well and Department of State civilians. Through the course of the war, the JCS and services determined that joint education was a necessary component of leadership development for victory.

Determining Post-War Joint Education

Throughout the conflict, the services and JCS held a series of boards and committees to determine the requirement for and direction of service PME and joint education. On 7 September 1945, Marshall cabled Eisenhower, still the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, but the heir apparent as the next CSA, “The reactivation of the [Army] War College appears to be dependent upon the future of ANSCOL. If we have a Joint War College properly organized and directed neither an Army nor a Navy War College would appear to be necessary.” By contrast, the Navy saw its war college as the centerpiece of its officer education system. Marshall’s views and those of the JCS led the Army to convene a board that would make far-reaching recommendations about post-war joint education and the USAWC.

The War Department Military Education Board convened on 23 November 1945 under the direction of Lieutenant General Leonard T. Gerow, and took the idea of joint education to a new level. Known as the “Gerow Board,” this body of senior officers designed the Army’s post-war educational system and introduced a visionary framework of joint education. The board dealt with many unknowns including the size and organization of the post-war Army, and the future status of the Army Air Force, which was formerly resolved by the National Security Act of 1947. On 5 February 1946, the Gerow Board submitted a comprehensive report, providing an educational system for all components of the Army nested within a joint framework.

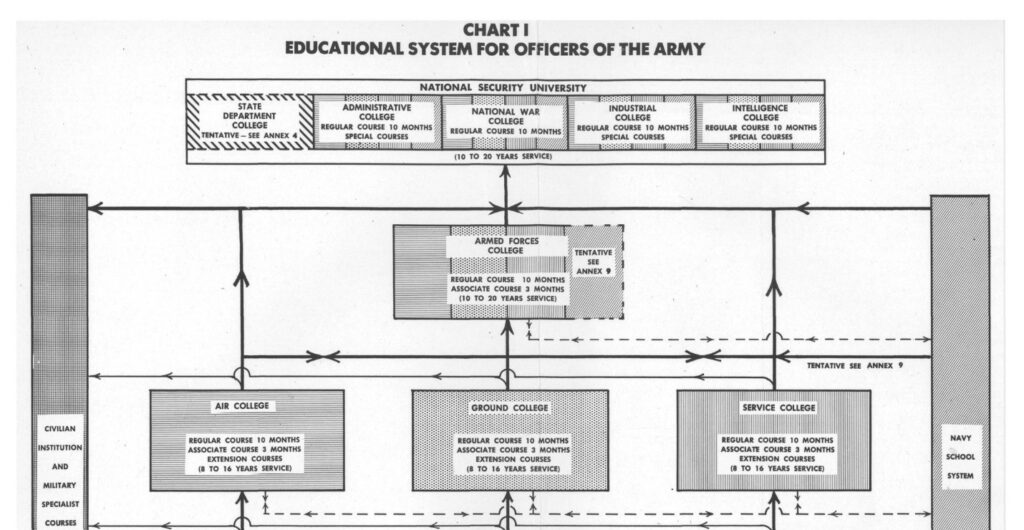

For senior joint education, the board recommended the establishment of a National Security University, supervised by the JCS and the Under Secretary of War, to “assure the development of officers capable of high command and staff duties in the connection with prevention of war, preparation for and prosecution of war on a global scale, and the execution of the responsibilities of the Armed Forces subsequent to hostilities.” The board envisioned five colleges under the umbrella of the National Security University, including an Administrative, Intelligence, National War, Industrial, and State Department College. The board proposed that National would, “cover part of the instruction formerly included in the scope of the Army War College and the Army and Navy Staff College.” Objectives included promoting “understanding and coordination of effort between the Army, Navy, other Governmental agencies, and civil activities.” Clearly the board viewed joint and interagency coordination as vital for prosecuting and winning wars.

The board also recommended the establishment of an Armed Forces College, one level below the National Security University, under the supervision of either the War Department or Joint Staff. This school, the former wartime ANSCOL, had the mission to “provide instruction to insure [sic] efficient over-all establishment and direction of theaters, and the most effective separate and combined strategical, tactical and logistical employment of Air, Ground, Naval and Service Forces assigned thereto.” The rationale of this system was that officers attended the Air, Ground, or Service College – similar to today’s Command and General Staff College, prior to selection to either the Armed Forces College or one of the five colleges under the National Security University.

The Gerow Board’s report foreshadowed the demise of the USAWC. The report stated, “The former mission of the Army War College has been assigned to … the National Security University and the Armed Forces College. Therefore, the Army War College need not be reopened.” On 4 February 1946, one day before the publication of the Gerow Board’s report, the JCS, in conjunction with the War, Navy, and State Departments, formally established the National War College from the existing Army-Navy Staff College. The timing was coincidental with concurrent staffing of the Gerow Board’s report and the new joint war college proposal. The Armed Forces Staff College stood up on 13 August 1946 in Norfolk, Virginia, while the National War College opened its doors in September 1946 in the former USAWC facilities. The JCS also renamed the Army Industrial College as the Industrial College of the Armed Forces, with a status on par with National. The Army’s vision of post-war joint education was coming to fruition, although with unintended consequences, specifically the newly formed Air Force established the Air War College in Maxwell, Field, Alabama, at the same educational level as National and the still open NWC.

Eisenhower and his replacement, General Omar Bradley, both realized significant shortcomings of the National and the Industrial College but deferred the decision to reopen USAWC to the next CSA, General Lawton Collins. Collins accepted the Army Staff’s recommendation in late 1949 to restart the college in 1950 at Ft. Leavenworth before permanently moving the following year to Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. Before long, each of the services had a war college, with the Marine Corps adding its own in 1990. Within four years, the Army’s joint PME vision was relegated to the filing cabinet of good ideas not implemented.

The National Defense University established by the JCS in 1976, has grown to include the National War College, Industrial College of the Armed Forces (now Eisenhower School for National Security and Resource Strategy), Joint Forces Staff College (formerly Armed Forces Staff College), College of Information and Cyberspace and College of International Security Affairs. Separately, the Department of State created the Foreign Service Institute (FSI) in 1947 and the Defense Intelligence Agency opened what is now the National Intelligence University (NIU) in 1962. Although the latter two are not SSCs, they do serve the purpose of educating Foreign Service officers, military, and defense civilians for positions of increased responsibility.

The Need for a Truly Joint PME Framework

The dissipation of the Army’s vision of 1946 allowed the services to continue to operate on their own and see the future through a narrow lens, which led to joint interoperability failures during the late 1970s and early 1980s in Operations EAGLE CLAW and URGENT FURY. These high visibility shortcomings led to the enactment of Goldwater-Nichols in 1986, which among many improvements, mandated JPME within the JCS education framework. The multiple SSCs today provide JPME credit to students, but the majority are service institutions with 40% of faculty and students from other services. Additionally, the newest service, U.S. Space Force, recently announced it will leverage a civilian institution for its Senior Developmental Education programs. Almost 37 years after the passage of Goldwater-Nichols, the DoD and JCS have continued to identify significant shortcomings in JPME and joint warfighting.

The 2018 National Defense Strategy called out the “stagnation” of current PME and its value as a “strategic asset to build trust and interoperability across the Joint Forces and with allied and partner forces.” In 2020 the JCS declared, “The evolving and dynamic security environment…demands immediate changes to the identification, education, preparation, and development of our joint warfighters.” The document also states, “we must strengthen our interagency and intergovernmental perspectives.” Similarly, the recent report on the collapse of the Afghan Security Forces noted the, “United States lacked effective interagency oversight and assessment programs that were necessary to gather a clear picture of ANDSF development on the ground.” Kudos to these strategic leaders for not only reinvigorating direction on the need to improve PME across the joint force but also for greater integration with the interagency and allies and partners.

The JCS is also seeking new concepts to support Joint Operations across the Competition Continuum including the development of a new Joint Warfighting Concept. The Services have also been directed to create concepts such as Joint All-Domain Command and Control and Joint Fires. With this new effort toward improving JPME and warfighting, it’s essential for the Joint Staff to relook the Gerow Board’s recommendations. With key stakeholders such as Congress, Department of State, and the Intelligence community, the JCS can incorporate FSI and NIU into the existing SSC structure. Additionally, to improve jointness in the Service SSCs, the JCS must change the existing requirement for “U.S. military officer mix of no more than 60 percent of the total student body” to at least 50 percent. This increase in the other Services, civilian (to include interagency), and international officers, will help make the Service SSCs less “service focused” and move the DoD closer to the intent of the Gerow Board’s framework for joint education. Creating a National Security University will improve PME, joint warfighting, and interoperability across the DoD, interagency, and allies and partners in preparation for an uncertain future.

Douglas Orsi is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Command Leadership and Management (DCLM) at the United States Army War College. He is a retired Army colonel who has written previously on professional military education and mission command.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Army War College, Fort Lesley J. McNair, entrance on P Street between Third & Fourth Streets Southwest, Washington, District of Columbia, DC built 1903-1907. Roosevelt Hall housed the Army War College from 1907-1946. Since 1946, it has housed the National War College (NWC).

Photo Credit: William Smalling, photographer, via the U.S. Library of Congress

As a soldier and recent graduate of the National War College, I was the benificiary of those leaders who were dedicated to improving JPME. I agree with the proposal to adjust the cap for US military officers as the greatest strength of the cohort is the inclusion of both civilian senior leaders from across the national security enterprise and our foreign military partners, who are indispensable for our future security.