Diplomacy is, in its most basic form, the official means by which one state relates to other states or international organizations.

The acronym DIME is one of the most commonly used mental models across the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD). A shorthand for the four purported “instruments of national power”—diplomatic, informational, military, and economic—the construct presents a distorted view of diplomacy and perpetuates a bottom-up, checklist view of policymaking. “Thinking in DIME,” so to speak, conflates diplomacy with other policy instruments that link more naturally to tangible sources of national power, thereby obscuring the unceasing political role of the diplomatist to coordinate and marshal all kinds of national power to achieve goals abroad. This approach also encourages policymakers to think of diplomacy as akin to military instruments of power, as something to start and stop—or even combine and portion out with other swappable units of power—rather than as a fundamentally different, fundamentally political process that is never abandoned. In addition, and more dangerously, conceptualizing using DIME reinforces a natural bureaucratic tendency to subordinate strategy to resourcing by building foreign policy up from present capabilities rather than identifying the mix of capabilities needed to achieve established policy ends.

DIME Distorts the Character and Role of Diplomacy

Diplomacy is, in its most basic form, the official means by which one state relates to other states or international organizations. Relating to another state or organization, however, has two broad aspects: the instruments or practices of diplomacy and the overall management of a bilateral or multilateral relationship. “Diplomacy” can refer to either or both of these, depending on the speaker and context. Under the DIME construct, however, the “D” largely refers to the first definition of diplomacy: discrete diplomatic practices or implements that reside largely in the Department of State toolbox, such as breaking diplomatic relations, declaring a foreign diplomat persona non grata, withdrawing an ambassador in protest, démarching foreign officials, approving foreign arms sales, or placing visa bans on corrupt foreign officials.

These mechanisms of diplomacy may be effective in achieving policy goals, but they differ from military, economic, or informational tools. For starters, those three instruments encompass latent powers that the instruments can potentially transmit into real results. The United States has, using David Jablonsky’s “gauge for national power,” tremendous latent military power built on factors like personnel, equipment, weaponry, leadership, discipline, and relationships with allies. Similarly, the U.S. economy is the largest and one of the most productive in the world, fueled by natural resources, a large and growing population, international faith in dollar-denominated assets, advanced technology, an attractive market for investment, and factories that make things (including things to support the M). Dynamic ideas, cultural reach, attractive ideals, and dominance of social media and other communications platforms represent massive U.S. informational and ideological power, what E.H. Carr, one of the twentieth century’s most influential international relations authors, called the “power of persuasion.”

Giving diplomacy a letter in the DIME construct, however, encourages policymakers to imagine a matching reservoir of diplomatic power whose tap they can turn off and on—again, similar to military tools, which turn a matching latent military power into effects. Countries cooperate with diplomatic requests or demands because the proposed (or threatened) action in relation to that country will affect its security, its economy, or its international or internal influence or legitimacy. Diplomatic “power,” however, does not get this cooperation from other countries: Diplomacy changes other countries’ behavior because the arms, money, and power over opinion serve to back up the political ends that diplomacy communicates. That is, governments achieve international goals because diplomacy marshals the instruments that tap into one or more other, latent kinds of power.

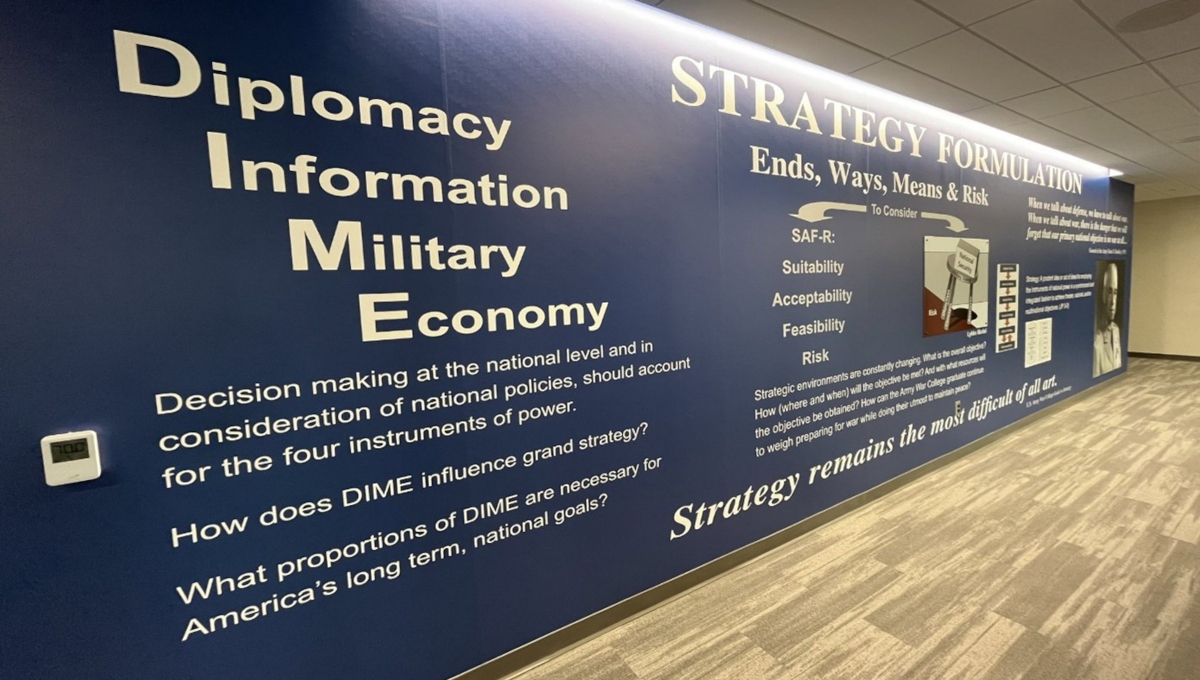

The “latent power” of diplomacy, then, is its role in bringing to bear the other three instruments of power. A large wall in the U.S. Army War College that features the DIME concept asks students, “What proportions of DIME are necessary for America’s long term, national goals,” obscuring this fundamental difference between diplomacy and the other tools. Rather than an instrument to be compared to and “portioned” out with other instruments, the main function of diplomacy is the actual or proposed portioning out of the instruments of power to achieve national goals.

This is why E.H. Carr did not include diplomacy in his list of the three separate, though often interdependent, kinds of political power countries use to pursue national goals in the international sphere: military power, economic power, and power over opinion. Carr—himself a diplomat for two decades—instead, placed diplomacy as “the art of applying the instruments of power rather than a separate instrument itself…[of] negotiating with friends, enemies, and neutrals backed always by the potential application of [the other three].” Robert Worley echoes Carr, defining diplomacy as the political instrument “backed by all the instruments of power.”

Diplomacy is not, as Clausewitz famously described war, the continuation of political relations by other means.

Diplomacy Is a Constant Process

Diplomacy is not, as Clausewitz famously described war, the continuation of political relations by other means. Diplomacy is rather international political relations qua relations, interactions between countries that include “constant assessment of other countries’ power potential, perceived vital interests, relationship with other states, in an attempt to maximize one’s own country’s freedom of action with the ultimate purpose of assuring the achievement of the nation’s vital interests, the core of which is survival.” As George Kennan, accomplished diplomat and one father of the Cold War containment strategy, wrote, “Diplomacy isn’t anything in a compartment by itself. The stuff of diplomacy is in the entire fabric of our Foreign Relations with other countries, and it embraces every phase of national power and every phase of national dealing.”

As Harold Nicolson noted, the core diplomatic role, negotiation, was not an opportunistic activity but “a permanent activity.” Although individual tasks will be completed, “managing relations with the host country and addressing the many multinational issues that the host nation may be involved in are a continuing operation. Embassy work has no defined end state because relations among states are ongoing.” Even military victory does not end diplomacy, as Kennan observed: “We may defeat an enemy, but life goes on. The demands and the aspirations of people, the compulsions that worked on them before they were defeated, begin to operate again.”

In this sense, the practice of diplomacy is the practice of international politics, and just as domestic politics are unending, politics beyond borders is the art of continually applying a nation’s power to achieve its goals. The DIME construct, therefore, not only pairs three letters (IME) that conceptually match up to related powers and instruments with another (D) that is instead the method for applying all instruments, but also groups a strange “instrument” of diplomacy that—in the face of the constant re-adjustments of relations between countries—the policymaker never sets down, with the I, M, and E instruments that come in and out of the toolbox as needed.

To draw on the musical meaning of “instrument,” on the international stage high-level diplomacy—be it done by the president, a secretary of state or defense, or an ambassador at post—is less like one of the instruments and more like the conductor. It is the voice and direction given to the domestic players and the resulting sound given to foreign ears and eyes, a kind of coordinating political power to use and guide the orchestra’s parts to achieve a greater whole that the conductor alone is responsible for. Various sections of the orchestra rest or fade into the background, but the conductor never stops.

Thinking in DIME upends effective policymaking.

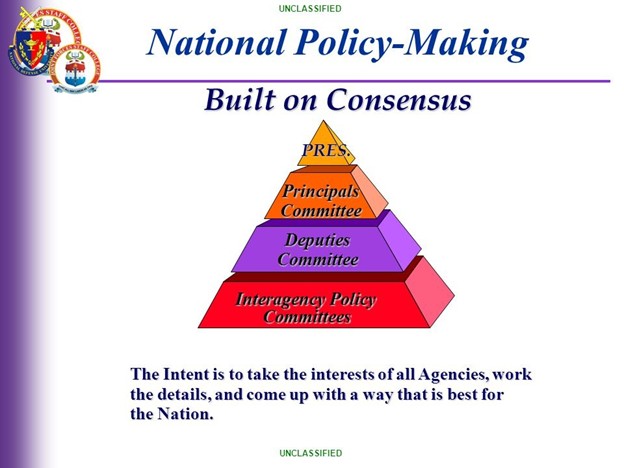

Policymakers ideally respond to an emerging international event or issue by deciding whether it’s in national interests to act, what the objective should be if so, what level of resources to dedicate to the action, and what instruments will best deliver that level of resources to the problem. However, as Graham Allison related in Essence of Decision when analyzing the Cuban missile crisis, the process can often go the other way: Policymakers presented options to President John F. Kennedy “based largely on the core competencies and existing plans of the organizations that made up the national security establishment (diplomatic action from the State Department, airstrikes from the U.S. Air Force, a blockade from the U.S. Navy).” Pre-existing plans and bureaucratic missions drove options, with policies emerging “as a result of the struggle among organizations to enshrine their priorities,” a form of working backwards from instruments to policy.

There will always be this strong tendency for the immediate stewards of the various instruments of power—whether at State, DoD, or other policy agencies—to jockey for position based on organizational interests and instruments, subordinating strategy to resourcing. Then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld recognized this danger and sought to avoid a “bottom-up” planning process based on service-specific programs by reordering military planning to promote a “top-down” system to work from ends to identify needed joint combat capabilities, properly beginning with broad requirements without regard to individual services.

The process for developing national security policy documents implicitly recognizes the proper relation of policy the instruments of power. Within the Department of State, for example, the President’s National Security Strategy (NSS) guides the State/USAID Joint Strategic Plan (JSP), which in turn guides the writing of regional and functional bureau strategies, and finally the integrated country strategies (ICS) of each overseas mission. At the ICS level, the various embassy offices then identify the tools and processes to help achieve these detailed versions of national-level objectives, along with, when appropriate, timelines for achievement.

However, when DoD doctrine and schools conceptually group diplomacy and other diverse and ambiguous kinds of power into simplified “instruments” of national power under the DIME (or the expanded universe of MIDFIELD, or MIDLIFE, or DIMEFIL), they reinforce the tendency to build foreign policy up from present capabilities in a checklist or “lines of effort” process based on an audit of instruments at hand, rather than identifying the mix of capabilities policymakers need—or need to create—to achieve established policy ends. Rather than enriching our thinking of how to interact with the world, therefore, DIME often simplifies it in a dangerous way, allowing the bureaucratic policy model (Allison’s “governmental politics”) to thrive. Teaching instruments of power in this way to war college students ignores Jeffery Meiser’s warning against seeing strategy as “means-based planning” that is “inherently uncreative, noncritical, and limits new and adaptive thinking.”

Conclusion

All models are limited and imperfect, and the DIME model does remind professional military education graduates and other potential security policymakers to recognize and consider non-military instruments of power and reflect on the importance of diplomacy in our relations with the world. However, DoD-led attempts to mold diplomatic work, work largely done by the Department of State, to mirror its concept of the “M” ultimately hinders, rather than aids, understanding of diplomacy, which is of a fundamentally different nature than military capability. In effect, DIME is DoD trying to fit diplomacy—the unending human relationship process—into a kind of mental toolbox for policymakers to reach into and find the right tool for a current problem. Of all the parts of the DIME, diplomacy in particular resists this approach, and creates an awkward grouping of diplomacy with instruments of power limits policymakers’ strategic imagination in managing ongoing political relations with other states. Just as you will fight as you train, you will strategize as you conceptualize; misguided concepts will create fragmented and less effective strategies.

Matthew O’Connor is a senior Foreign Service Officer at the Department of State and Professor of International Studies at the U.S. Army War College. His most recent State assignment was as senior energy officer in the Bureau of Energy Resources (ENR). His assignments prior to ENR were as political-military chief at U.S. Embassy Seoul; principal officer of the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT) in Kaohsiung; and senior Australia desk officer in the Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs (EAP) Office of Australia, New Zealand, and Pacific Island Affairs. Mr. O’Connor has also served as political-military chief at U.S. Embassy Baghdad and Consulate General Naha (Okinawa) and in the economic sections of AIT/Taipei, U.S. Embassy Tokyo, and Consulate General Shanghai.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, Department of State or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Strategy display in Root Hall at the U.S. Army War College.

Photo Credit: U.S. Army War College

From the first paragraph of our article above:

” ‘Thinking in DIME,’ so to speak, conflates diplomacy with other policy instruments that link more naturally to tangible sources of national power, thereby obscuring the unceasing political role of the diplomatist to coordinate and marshal all kinds of national power to achieve goals abroad.”

Question:

a. If “diplomacy holds in its quiver the potential use of force” (see midway down Paragraph 2, of Page 2, of the paper “Diplomacy as an Instrument of National Power,” by Reed J. Fendrick),

b. Then does this help to explain — and indeed help to reinforce — at least one point that the author (Matthew O’Connor), in our article above (“The Problem with Thinking in Dime”), is making?

(It appears that the “Diplomacy as an Instrument of National Power” item — that I note at my item “a” above — this can also be found at DIPLOMACY AS AN INSTRUMENT OF NATIONAL POWER, VOLUME I: THEORY OF WAR AND STRATEGY, Strategic Studies Institute, US Army War College [2008]?)

Near the end of the third paragraph of our article above:

” … Dynamic ideas, cultural reach, attractive ideals, and dominance of social media and other communications platforms represent massive U.S. informational and ideological power, what E.H. Carr, one of the twentieth century’s most influential international relations authors, called the ‘power of persuasion.’ ”

Question: As to this such “I” instrument of national power, might we say that it has taken a big “hit” since the end of the Old Cold War?

a. First, due to our post-Cold War prioritization of the wants, needs and desires of market society; these, over the wants, needs and desires of other communities? (Throughout the world, and even here at home, this emphasis on “liberalism” tending to threaten the power, influence, control, privilege, prestige, safety, security, etc., of everyone — everywhere — who who depended on the status quo for same?) And:

b. Later, due to the worldwide revolt against these such actions. (An event which saw much of the world — thus threatened — moving to the other extreme, of embracing traditional social value, attitudes and beliefs; these, instead of more market-based ideas and ideals?)

From this such perspective, thus, to see America — post-the Old Cold War — taking a double “hit” as to the “I” item of American national power in DIME?

Conclusion: Neither America’s exclusively “liberal” ideas/ideals — nor America’s exclusively “traditional” social ideas/ideas — would seem to provide the United States, and thus our diplomats, with our (former) ability to keep the “I” capitalized in DIME.

(Something that our statespersons, and soldiers of today, must learn to deal with, to wit: DiME?)

Diplomacy is not singular and by itself doesn’t exist. Diplomacy is the reasoned application of information, military and economic power to achive national goals. In and of itself Diplomacy has no power it is mearly nations treating each other courtesy