Today we have gathered and we see that the cycles of life continue. We have been given the duty to live in balance and harmony with each other and all living things. So now, we bring our minds together as one as we give greetings and thanks to each other as people.

It’s tradition at War Room to present a Thanksgiving message each year as we approach the holiday. As people in the United States prepare to celebrate tomorrow, there is a great deal in the world that aims to divide rather than unify, and it’s far too easy to lose sight of what there is to be thankful for. This year, rather than citing a historical senior leader, we’ve chosen to share the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address.

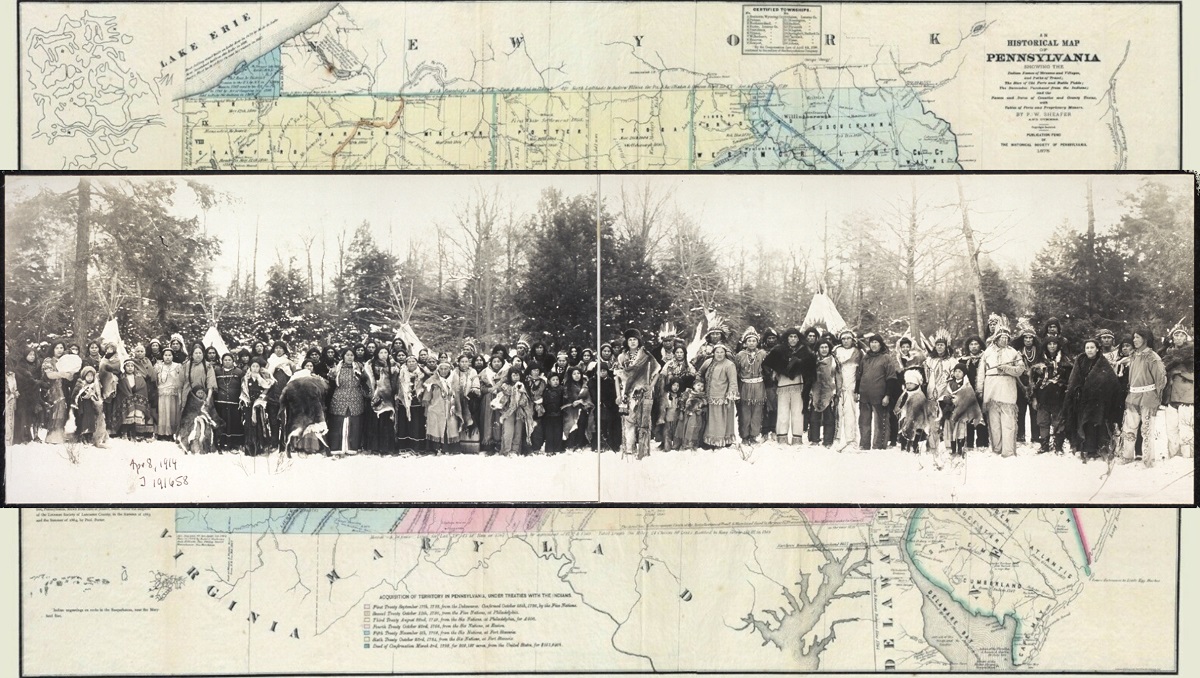

The Haudenosaunee (hoe-dee-no-SHOW-nee), often referred to in English as the Iroquois, are a confederacy of nations in the northeast United States and parts of Canada. They lived for a time in portions of western, central, and eastern Pennsylvania, to include what is today Carlisle Barracks—home of the U.S. Army War College. Haudenosaunee means “people who build a house.” A misnomer, Iroquois was actually the language of the six nations that make up the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. They are the Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Tuscarora and Seneca.

Carlisle Barracks has an unfortunate history with the people of the six nations in that it was once the location for the Carlisle Indian School, which operated from 1879 to 1918. During those 39 years, thousands of native American children attended the school; at least 186 died and were buried here. To learn more about the history of the school and what the Department of Defense is doing to correct the failings of the past, visit The Carlisle Indian School Project.

To honor the people of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, we humbly offer their traditional Thanksgiving Address, or the Ohèn:ton Karihwatéhkwen. The address is often recited at the opening and closing of gatherings to get everyone in a good mind to work together for the best for all.

From War Room to our valued readers and listeners, we are thankful for your continued engagement. We hope that you find time to be thankful for the good in your life.

Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address

The People

Today we have gathered and we see that the cycles of life continue. We have been given the duty to live in balance and harmony with each other and all living things. So now, we bring our minds together as one as we give greetings and thanks to each other as people.

Now our minds are one.

The Earth Mother

We are all thankful to our Mother, the Earth, for she gives us all that we need for life. She supports our feet as we walk about upon her. It gives us joy that she continues to care for us as she has from the beginning of time. To our mother, we send greetings and thanks.

Now our minds are one.

The Waters

We give thanks to all the waters of the world for quenching our thirst and providing us with strength. Water is life. We know its power in many forms- waterfalls and rain, mists and streams, rivers and oceans. With one mind, we send greetings and thanks to the spirit of Water.

Now our minds are one.

The Fish

We turn our minds to the all the Fish life in the water. They were instructed to cleanse and purify the water. They also give themselves to us as food. We are grateful that we can still find pure water. So, we turn now to the Fish and send our greetings and thanks.

Now our minds are one.

The Plants

Now we turn toward the vast fields of Plant life. As far as the eye can see, the Plants grow, working many wonders. They sustain many life forms. With our minds gathered together, we give thanks and look forward to seeing Plant life for many generations to come.

Now our minds are one.

The Food Plants

With one mind, we turn to honor and thank all the Food Plants we harvest from the garden. Since the beginning of time, the grains, vegetables, beans and berries have helped the people survive. Many other living things draw strength from them too. We gather all the Plant Foods together as one and send them a greeting of thanks.

Now our minds are one.

The Medicine Herbs

Now we turn to all the Medicine herbs of the world. From the beginning they were instructed to take away sickness. They are always waiting and ready to heal us. We are happy there are still among us those special few who remember how to use these plants for healing. With one mind, we send greetings and thanks to the Medicines and to the keepers of the Medicines.

Now our minds are one.

The Animals

We gather our minds together to send greetings and thanks to all the Animal life in the world. They have many things to teach us as people. We are honored by them when they give up their lives so we may use their bodies as food for our people. We see them near our homes and in the deep forests. We are glad they are still here and we hope that it will always be so.

Now our minds are one.

The Trees

We now turn our thoughts to the Trees. The Earth has many families of Trees who have their own instructions and uses. Some provide us with shelter and shade, others with fruit, beauty and other useful things. Many people of the world use a Tree as a symbol of peace and strength. With one mind, we greet and thank the Tree life.

Now our minds are one.

The Birds

We put our minds together as one and thank all the Birds who move and fly about over our heads. The Creator gave them beautiful songs. Each day they remind us to enjoy and appreciate life. The Eagle was chosen to be their leader. To all the Birds-from the smallest to the largest-we send our joyful greetings and thanks.

Now our minds are one.

The Four Winds

We are all thankful to the powers we know as the Four Winds. We hear their voices in the moving air as they refresh us and purify the air we breathe. They help us to bring the change of seasons. From the four directions they come, bringing us messages and giving us strength. With one mind, we send our greetings and thanks to the Four Winds.

Now our minds are one.

Closing Words

We have now arrived at the place where we end our words. Of all the things we have named, it was not our intention to leave anything out. If something was forgotten, we leave it to each individual to send such greetings and thanks in their own way.

Now our minds are one.

This translation of the Mohawk version of the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address was developed, published in 1993, and provided, courtesy of: Six Nations Indian Museum and the Tracking Project All rights reserved.

To hear the the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address spoken in Mohawk follow this link with the recitation beginning at approximately 01:55 in the embedded video at the top of the page.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Captioned -1914 – Buffalo New York, Panoramic View of Iroquois.

Photo Credit: William Alexander Drennan courtesy of the Library of Congress, Public Domain

Thank you for this thanksgiving address. It seems far wiser than most I have heard.

I am very pleased to see that you have posted this Thanksgiving address of the Haudenosaunee! May you receive many blessings!

Thank you and God bless you all, happy thanks Giving

I too am pleased, and pleasantly surprised, to find your honoring of The Thanksgiving Address. I did not a few small typos though, that the Haudenosaunee “were” a confederacy of nations e.g. The Six Nations Confederacy, from whom Benjamin Franklin borrowed several key provisions for our Constitution, “are” still very much with us today, despite the Carlisle Indian School, etc. Thanks again for the post.

Kevin thank you for your comment. When crafting the intro we were stuck thinking of a particular time period and incorrectly used the past tense. We have corrected the verbiage to reflect that the people of the Six Nations Confederacy are definitely still with us. Thanks for the editorial help.

I am a descendant of Chief Joseph Brant through his sister Moly (or Poly) and her husband Sir William Johnson, the King’s representative to the Haudenosaunee. Throughout their lifetime, both Chief Joseph and Sir William translated portions of the Bible into Mohawk (both spoke Mohawk and English). Thank you for this new, to me, information surrounding Carlisle.

There is a wonderful chapter in the extremely wonderful book by Robin Wall Kimmerer, “Braiding Sweetgrass” that introduces the Haudenosaunee “Thanksgiving Address.”

It starts on page 105 under the chapter heading, “Allegiance to Gratitude.”

It would be best if your students understood that warfare was endemic with the Native Americans. The Eastern Native Americans were at war before European settled in North America. When they took captives, some were tortured to death as a way of revenge and to mourn those of their tribe killed their conflicts.

‘The Cutting-Off Way’ Review: Native Americans at War: Before and after the arrival of Europeans, indigenous American fighters employed battlefield tactics that turned on surprise and outmaneuvering the enemy. By Stephen Brumwell Updated Oct. 4, 2023 6:05 pm ET

https://www.wsj.com/arts-culture/books/the-cutting-off-way-review-native-americans-at-war-f256e061

The Cutting-Off Way: Indigenous Warfare in Eastern North America, 1500–1800 Kindle Edition by Wayne E. Lee

Invisible Armies by Max Boot

It is not hard to see why prejudice against guerrillas has been so pervasive. Prestate warriors are, in the words of John Keegan, “cruel to the weak and cowardly in the face of the brave”18—precisely the opposite of what professional soldiers have always been taught to revere. They refuse to grapple face-to-face with a strong foe until one side or the other is annihilated in the kind of warfare immortalized, if not invented, by the Greeks.

Battles among nonstate peoples have often consisted of nothing more than two lines of warriors decked out in elaborate paint shouting insults at one another, making rude gestures, and then discharging spears, darts, or arrows from such long range that they inflict few casualties. Primitive societies lack an organizational structure that can force men on pain of punishment to engage in costly close-quarters combat in defiance of a basic instinct for self-preservation. This has led some observers to suggest that nonstate peoples do not

engage in warfare at all but rather in “feuds” or “vendettas” that are for the most part ceremonial and have little in common with “true” war as practiced at Cannae, Agincourt, or Gettysburg. After moving to Massachusetts in the seventeenth century, for example, a professional English soldier wrote with scorn that Indians “might fight seven years and not kill seven men” because “this fight is more for pastime, than to conquer and subdue enemies.”19

What such critics overlook is that battles constitute only a small part of primitive warfare. Most casualties are inflicted not in these carefully choreographed encounters but in what comes before and after—in the stealthy forays of warriors into the territory of their neighbors. The anthropologist Lawrence Keeley writes, “One common raiding technique (favored by groups as diverse as the Bering Straits Eskimo and the Mae Enga of New Guinea) consisted of quietly surrounding enemy houses just before dawn and killing the occupants by thrusting spears through the flimsy walls, shooting arrows through doorways and smoke holes, or firing as the victims emerged after the structure had been set afire.”20

Following such an attack, the raiders might disperse before large numbers of enemy warriors could arrive, only to return a few days later, hoping to catch another enemy village unawares. All adult men participate in this type of warfare, and quarter is seldom asked or given. Surrender for warriors is not an option; if they suffer the dishonor of defeat, they are either killed on the spot or, as was common among the Iroquois Indians of northeastern North America, they might be tortured to death and then partially eaten. At the end of such an encounter, the victor rapes the loser’s women, enslaves them and their children, burns crops, steals livestock, destroys the village.

Primitive warfare has been consistently deadlier than civilized warfare—not total numbers killed (tribal societies are tiny compared with urban civilizations) but in the percentage killed. The Dani tribesmen of New Guinea, the Dinka northeast Africa, the Modoc Indians of California, the Kalinga headhunters of the Philippines, and other nonstate peoples studied by ethnographers over the past two centuries suffered considerably higher death rates from warfare annually (sometimes five hundred times higher) than did the most war-ravaged European countries, such as twentieth-century Germany and Russia. The average tribal society loses 0.5 percent of its population in combat every year.21 If the United States suffered commensurately today, that would translate into 1.5 million deaths, or five hundred 9/11’s a year. Archaeological evidence confirms that such losses are no modern anomaly: at one early burial site in the Sudan, Djebel Sahaba, which was used sometime between 12,000 and 10,000 BC, 40 percent of the skeletons showed evidence of stone arrowheads; many had multiple wounds.22 That shows the ubiquity and deadliness of warfare at a time when, to the modern eye, guerrillas would have been barely fistinguishable in intellectual dophistication from gorillas.

There was little ideology or strategy behind the kind of war waged among tribal warriors in prerecorded times or even more recently. They did not employ “lightning raids by ad hoc companies,”23 in the words of one modern scholar, because they concluded, after careful consideration of all the alternatives, that this was the surest way to hurt their foes. They fought as they did simply because it was the

way their fathers had always fought, and their grandfathers before them. It was all they knew. That sort of instinctual guerrilla warfare remained the commonest kind until recent centuries.

What is interesting is how the Native Americans adapted to European tactics in defending themselves.