Trường Chinh remains a revered figure in Vietnam, but today few scholars and national security professionals study his writings on revolutionary warfare.

Võ Nguyên Giáp, the Vietnamese communist general, is a well-recognized figure of the Indochina Wars that occurred in the mid-twentieth century. He is most famous for his victory over French military forces at Dien Bien Phu in 1954 during the First Indochina War (1946-54) between France and the Viet Minh Front, a Communist-led organization fighting for Vietnam’s independence from that colonial power. Giap is also renowned for his treatise People’s War, People’s Army, published in English in 1962, which provides his concepts of the strategy and tactics of guerrilla and revolutionary warfare and their application. Yet in that publication, Giap pays homage to another important figure in Vietnamese military affairs, Trường Chinh, who Giap credits for making “an important contribution to the thorough understanding of the Resistance War line and policies of the [Communist] Party” by providing a theory of war and strategy for the armed struggle and the development of the revolutionary armed forces. Trường Chinh remains a revered figure in Vietnam, but today few scholars and national security professionals study his writings on revolutionary warfare.

Trường Chinh was born Đặng Xuân Khu on February 9, 1907, Ha Nam Ninh province, Vietnam. He joined Ho Chi Minh’s Vietnamese Revolutionary Youth Association, the “cradle of communism in Vietnam,” in 1928, and participated in an anti-colonial strike that resulted in his arrest and expulsion from the local high school. He moved to Hanoi where he graduated from a lycée, enrolled in the School of Higher Commercial Studies, and worked as private a teacher but also pursued politics as a member of the newly formed Indochinese Communist Party (ICP). As the co-editor of a communist newspaper, the French police arrested him in 1930 for subversive activities, and the court sentenced him to twelve years of penal servitude. Paroled in 1936, he became a member of Ho’s inner circle because most of the party’s early leaders were dead or exiled. In 1941, he surfaced as the ICP’s general secretary and ultimately, its leading theoretician. Around this time, he adopted the pseudonym Trường Chinh (“Long March”), in tribute to Mao Zedong’s famous military retreat during the Chinese Civil War.

In late 1947, with the First Indochina War now ongoing with France, Trường Chinh published the book Giap alluded to: The Resistance Will Win. He borrowed freely from Mao’s teachings on guerrilla warfare and especially protracted war, often without attribution. In the view of historian William Duiker, it was the “first major exposition of Vietnamese revolutionary strategy since the formation of the Vietminh Front” in 1941.

Trường Chinh began his treatise by arguing that the current conflict was a people’s war “aimed at achieving national independence, democracy and freedom” from the French colonialists, while also an agrarian revolution through confiscating land and other property from Vietnamese landlords (“feudalists”). To accomplish these objectives, he specified four lines of resistance (effort): political, economic, cultural and military.

Political resistance necessitated mobilizing and uniting the entire people under the leadership of the national front to wage the war against the French and their Vietnamese “feudal” élite and “comprador bourgeoisie,” and to win material and moral aid from supporters in the international arena. Economic resistance would destroy the colonial economy through sabotage while building a self-reliant Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) economy. Lastly, cultural warfare could break the bonds of French culture, using art and literature to propagandize and enlighten the masses.

Trường Chinh emphasized that the conflict was “political struggle” based on socio-political mobilization, but the book’s main emphasis was on military resistance. Military resistance entailed a strategy of protracted war because the balance of forces at the moment favored the French. Time was the “best strategist,” he wrote—time to organize, train, and learn tactics. Additionally, the lengthier the war, the more likely the French population would become demoralized, revolutionary movements in other French colonies would emerge and require the government to spread its forces to quell rebellions, and world opinion would turn against France.

The character of this war in the early days was one without “battle-fronts,” i.e., an interlocking of conventional and guerrilla warfare using both hit-and-run tactics as well as isolating and destroying smaller enemy forces when the situation permitted. However, long-term resistance required the buildup of a regular army to attack the enemy’s front, guerrilla forces to attack the rear, and militia for regional self-defense and as a reserve for the regular army. Long-term resistance demanded resilience, but a more sophisticated military strategy, too.

Given the war’s character and his assessment of the difficulties, strengths, and weaknesses of each side, Trường Chinh specified that the military strategy of resistance had three stages, although there was no clear dividing line between them: defensive stage, stage of equilibrium, and stage of general counteroffensive. The enemy’s strategy in the first stage was offensive: to control cities, lines of communication, and where possible, large areas with its preponderance of forces and capability; and to sow discord between the Viet Minh and the people. The front’s strategy was defensive; use guerrilla tactics in the cities and countryside to attack constantly and retreat into safe areas. As the enemy advanced from the cities, it extended its lines of supply and communication (war of position), thereby creating opportunities for the front’s regular forces to stop the advance and encircle the enemy, exploiting tactical surprise or local superiority (mobile/maneuver warfare), while guerrilla warfare continued.

Trường Chinh warned that this stage, [equilibrium,] was complex, difficult to execute, and required time, but was critical as it was the stage that allowed the front to advance to the next phase.

The stage of equilibrium occurred when the two forces became relatively equal; absolute superiority was not a prerequisite. The enemy was now on the defensive without the strength to advance, but determined to consolidate its positions and communications lines by conducting “mopping up” operations and restoring political order in occupied areas. The front, however, prepared for the general counteroffensive: training cadres, building even more conventional and guerrilla forces, and developing revolutionary organizations. Additionally, it executed local attacks in enemy-occupied areas to harass and exhaust the enemy, counter its operations, commit sabotage, and destroy enemy units piecemeal. Guerrilla warfare predominated, but regular forces trained guerrillas and conducted mobile warfare when the situation allowed. Positional warfare, that is, static frontlines and large-scale combat operations, supported the other two forms of warfare. Trường Chinh warned that this stage was complex, difficult to execute, and required time, but was critical as it was the stage that allowed the front to advance to the next phase.

In the counteroffensive stage, the balance of forces now favored the Viet Minh because protracted war had drained the enemy’s morale and capability in Vietnam and metropolitan France. Tactically, mobile warfare campaigns played the first crucial role, with regular forces and large guerilla units acting as regular forces, but eventually evolving into positional warfare. Faced with defeats, the enemy retreated into the cities and strong points, which the Viet Minh attacked constantly to encircle and annihilate the enemy. This stage, although the briefest, brought decisive victory.

The conflict, he reiterated, was in the defensive strategy currently, consequently the ill-trained Viet Minh must optimize its guerrilla warfare advantages (e.g., climate, terrain, and population), defend important positions, and take the initiative to lure and harass, attrite, and whenever possible, annihilate the enemy locally. Equally important was forming a regular army and militia for the next stage, which would arise eventually. However, discerning the moment to move to this stage called for sound judgment and analysis: “when our leadership is skillful we can take advantage of favorable conditions of our time and situation.”

As one of the leaders, Trường Chinh influenced the strategy’s implementation as well. By 1951, he held that the Viet Minh should prepare for the counteroffensive as the strategic environment had changed with the Communist victory in China and a crumbling French empire. Likewise, the balance of forces was now in the DRV’s favor. It had substantial Sino-Soviet assistance, to include Chinese military advisors, formed a capable regular army of divisions with essential command and control and support elements, and mobilized the society. Unfortunately, Giap made tactical blunders in 1951 and 1952 when he attacked superior French forces that crushed his units. But Giap learned and loyally followed Trường Chinh’s strategy that led to success at Dien Bien Phu.

In the early 1960s, as the U.S. Army and Joint Staff developed its broad doctrine on counterguerrilla operations in response to the emerging national wars of liberation, it fixated on the writings of Mao and Giap for background. Bernard Fall pointed out, however, in Primer for Revolt (1963): “It was Trường Chinh, rather than Mao, that Giap read as he prepared his first offensive against the French, in 1951.” A few years later, the Central Intelligence Agency recognized Trường Chinh not only as the mastermind behind France’s defeat, but detailed how the North Vietnamese were applying his strategy in the ongoing Vietnam War. Yet, it is not apparent that the military used this insight to fashion its military strategy to avoid the strategic and tactical errors the French committed.

Sun Zi’s dictum, “If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat,” proved fitting. The preoccupation with Mao and Giap was understandable but was misguided; the military read the wrong strategist. Trường Chinh made use of Mao’s model of protracted war, but he deviated from it in two important ways regarding the operational and strategic environments. First, China’s geographical vastness was not mandatory for success; extensive and secure base areas for guerrilla operations could be established within the small country of Vietnam. Second, declining public morale and sympathetic world public opinion had outsized influence. Political and diplomatic efforts supported military power to achieve victory at the negotiating table or on the battlefield. In the First Indochina War and the Vietnam War these factors proved decisive.U.S. intelligence analysts recognized Trường Chinh’s impact on North Vietnamese military strategy. However, that knowledge did not result in the formulation of an effective U.S. counterstrategy. There is an important lesson here for policymakers and military leaders: development of a theory of victory to counter an adversary’s strategy requires an appreciation for specific strategic and operational contexts. Moreover, its formulation demands more than reading texts to devise generic doctrine. It deserves careful and immersive study of the enemy’s culture and theory of warfare to respond effectively. The army’s development and implementation of AirLand Battle doctrine against the Soviet Union is an apt example and one worth emulating as it seeks to address immediate threats and pacing challenges.

Frank Jones is a Distinguished Fellow of the U.S. Army War College where he taught in the Department of National Security and Strategy. Previously, he had retired from the Office of the Secretary of Defense as a senior executive. He is the author or editor of three books and numerous articles on U.S. national security.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

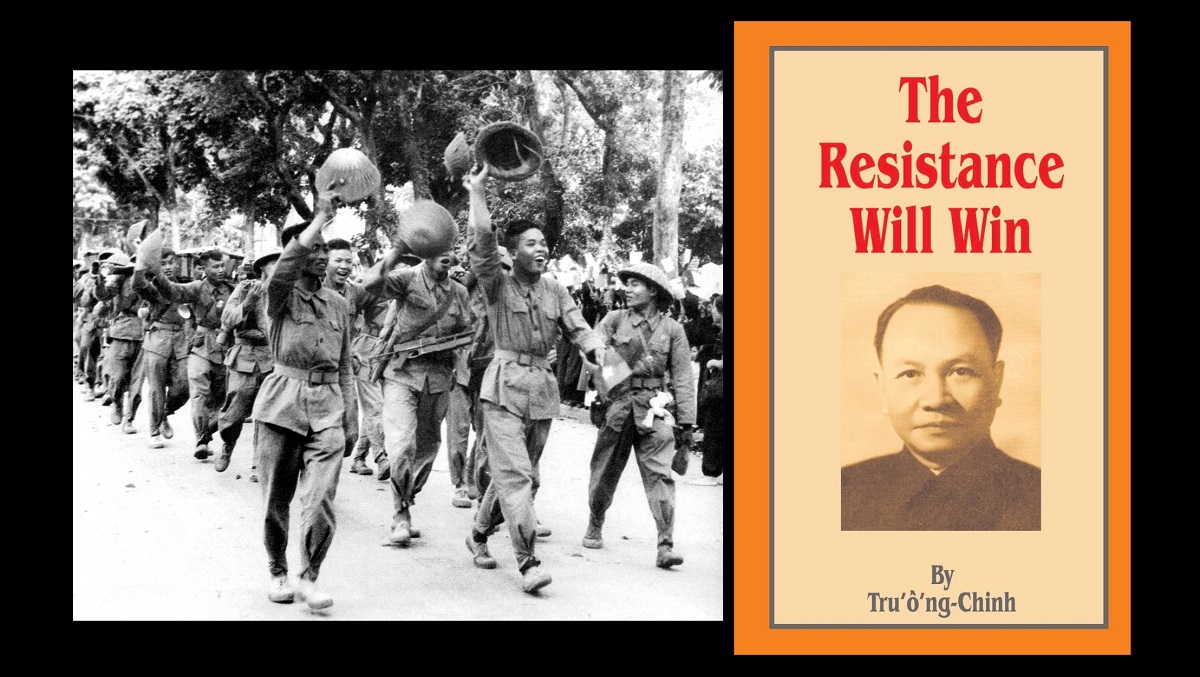

Photo Description: October 9, 1954. Waving to the city’s populace, joyous Viet Minh troops enjoy a “parade of victory” through the streets of Hanoi following the French withdrawal. Thousands of Vietnamese civilians crowded the capital’s streets waving flags, cheering and throwing flowers to the crowd of soldiers at the end of the French Indochina War.

Photo Credit: George Esper, The Eyewitness History of the Vietnam War, Associated Press 1983

Thank you so much.

From the concluding paragraph of our article above:

“There is an important lesson here for policymakers and military leaders: development of a theory of victory to counter an adversary’s strategy requires an appreciation for specific strategic and operational contexts. Moreover, its formulation demands more than reading texts to devise generic doctrine. It deserves careful and immersive study of the enemy’s culture and theory of warfare to respond effectively.”

Question:

If the development of a theory of victory, to counter an adversary’s strategy, requires an appreciation for specific strategic and operational contexts, then might the following, posst-Cold War, strategic and operational contexts prove useful?:

1. Post-the Old Cold War, the goal of the U.S./the West (both here at home and there abroad) was to achieve such political, economic, social and/or value changes as were considered necessary; this, so as to provide that both our states and societies, and those of the rest of the world also, might come to be better interact with, better provide for and better benefit from such things as (now both more accepted and more dynamic) democracy, capitalism, markets and trade.

(Problem: This “universal” U.S./Western political, economic, social and/or value change initiative, this “universally” threatened those — both here at home and there abroad — who depended on and derived their power, influence, control, status, privilege, prestige, safety, security, etc. from the status quo.)

2. Post-the Old Cold War, and thus “universally” threatened by the U.S./the West’s such initiative, the U.S./the West’s opponents (our great power and small opponents, our state and non-state actor opponents and even our here at home in the U.S./the West opponents) (a) “universally” came to embrace “containment” and “roll back” strategies and (b) “universally” sought to employ all their capabilities/all their instruments of power and persuasion (not just “military”) in the service of same.

Question — Based on the Above:

Are an opponent’s “culture and theory of warfare” (see the conclusion of the quoted item that I provide at the beginning of my comment above me); are these likely to be effected/be changed; this, when one goes, for example, from (a) doing “offensive”/political, economic, social and value change missions (such as the Soviets/the communists did in the Old Cold War, and such as the U.S./the West has done in the post-the Old Cold War) to (b) doing “defensive” “containment” and “roll back” missions (such as the U.S./the West did in the Old Cold War, and such as Russia, China, etc., have done in the post-Cold War)?

With regard to the question of whether an opponent’s “culture and theory of warfare” might change, for example, when the opponent nation goes from DOING political, economic, social and/or value change to PREVENTING political, economic, social and/or value change; as to this such matter, consider the following:

The U.S./Western post-Cold War threat:

“Modern wars are often about changing other cultures. While many wars in history were about enrichment and honor, modern wars often pursue goals that aim at the annihilation of certain cultural traits like Prussian militarism after 1945 or the creation of new ones like a democratic way of life. The contemporary American wars of the 2000s are paradigmatic examples for this.” (See the second paragraph of the 2019 Strategy Bridge article “Strategy, War, and Culture: #Reviewing Military Anthropology” by Julian Koeck.)

Why and how a Nation (such as China’s) “Culture and Theory of Warfare” might change, in relation to this such threat:

“This may, in fact, be the missing explanatory element. Ideologies regularly define themselves against a perceived ‘other,’ and in this case there was quite plausibly a common and powerful ‘other’ that both (Chinese) cultural conservatism (Confucianism) and (Chinese) political leftism (Chinese socialism) defined themselves against. This also explains why leftists have, since the 1990s, become considerably more tolerant, even accepting, of cultural conservatism than they were for virtually the entire 20th century. The need to accumulate additional ideological resources to combat a perceived Western liberal “other” is a powerful one, and it seems perfectly possible that this could have overridden whatever historical antagonism, or even substantive disagreement, existed between the two positions.” (Items in parenthesis above are mine. See near the end of the Foreign Policy article “What it Means to Be ‘Liberal’ or ‘Conservative’ in China: Putting the Country’s Most Significant Political Divide in Context” by Taisu Zhang.)

At the concluding paragraph of our article above is a linked item (see “specific strategic and operational contexts”); a linked item which, in fact, is the October 2023 “Returning Context to Our Doctrine Returning Context” article by MAJ Robert Rose. At about the seventh paragraph down in this linked item, we find the following:

“The current state of U.S. Army doctrine parallels Israel’s in 2006. As codified in 2022’s Field Manual (FM) 3-0, Operations, the Army’s doctrine of multidomain operations (MDO) lacks the specificity to prepare the Army to win. It continues a trend since the end of the Cold War of doctrines that prioritize flexibility over specificity. Although it identifies Russia as ‘our acute threat’ and China as ‘our pacing challenge,’ it is vague on their political objectives and the situation in which we would fight them. We need to replace vague thinking with clear thinking by returning context to our doctrine.”

Question: So as to replace at least one aspect of this vague thinking (the political objectives of Russia and China) — this, with clearer thinking — as to this such objective, might the following prove useful?:

“In the information age, a state of terror such as the one that Putin’s Russia has become, cannot countenance states of consent, especially next door. It is Ukraine’s constitutional order — with its independent (though still troubled) judicial system, freedom of the press, multiparty politics, largely legitimate elections, vibrant civil society, and general respect for human rights — that Putin cannot tolerate, lest it provide too tempting an example for democratic activists in his own country who have vehemently opposed him at great risk to their lives and to the public in general that shares so many ties to the people in Ukraine. The ‘peaceful coexistence’ of the Cold War is, in this respect, not acceptable to Putin.” (See the “Real Security” article “Putin’s Real Fear: Ukraine’s Constitutional Order” by Philip Bobbitt.)

Based on the above, might we say that the clear political objective of Russia (as least as relates to Ukraine) — and the clear political objective of China also (at least as relates to Taiwan) — this is to eliminate and replace the “states of consent” status/the “constitutional order” status/the “independent” status of the “states of consent” which (a) exist on their very doorsteps and which, thus, (b) existentially threaten them?

(Note that, while the above may deal well [?] with the problem of clearly identifying and clearly stating the political objective of Putin re: Ukraine and Xi re: Taiwan — it does nothing to address the other “clarity” shortcoming noted at my initial quoted item above; this being, the need to provide some clarity on whether, we/ourselves, would fight Putin and Xi; this, to prevent them from eliminating and replacing the “states of consent” status/the “constitutional order” status/the “independent” status of Ukraine and/or Taiwan. Thus, [a] while “their” political objective is exceptionally clear, [b] “our” political objective/response, in relation to same, remains “vague?”)

At the very beginning of the concluding paragraph of our article above, the author notes Sun Zi’s dictum: “If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat.”

However to note, as I do in my comment immediately above, that this would not seem to be our problem today. Rather, our problem today would seem to be that (a) while we know the enemy (b) we do not seem to know/we would not seem to have defined ourselves?

I agree with B,C,’s comments above dated 16 Jan 2025 at 3:24 PM. I was sent to Vietnam in early December of 1965, just a few weeks after the First Cavalry Division completed its operations in the famous Ia Drang Battle. I was a replacement for one of their losses. I was assigned as a helicopter door gunner/crew chief at age 20, just a city kid who never saw a jungle or visited a foreign culture. I learned quickly about being at “The tip of the spear” during fire fights with the Viet Cong and NVA in the Central Highlands, from the Cambodian border to the sands of the South China Sea. After I retired, I set out to write my memoir of my experiences in the early years of the Vietnam War. My book was published by the military history publisher Casemate. The title is, “The Gunner and the Grunt: Two Boston Boys in Vietnam with the First Cavalry Division Airmobile”. Copies are with the Jefferson Cadet Library, USMA, NY, the Carlile Barracks Library, and the U.S. Army Aviation School Library, Fort Rucker, AL. It is available on Amazon, Walmart, Barnes & Noble, or from the publisher. If you want to know what it was like to participate in early “Search and Destroy” missions, this book will put you in the middle of the action as if you were sitting in my helicopter going into a hot LZ. Michael L. Kelley MSG Ret.