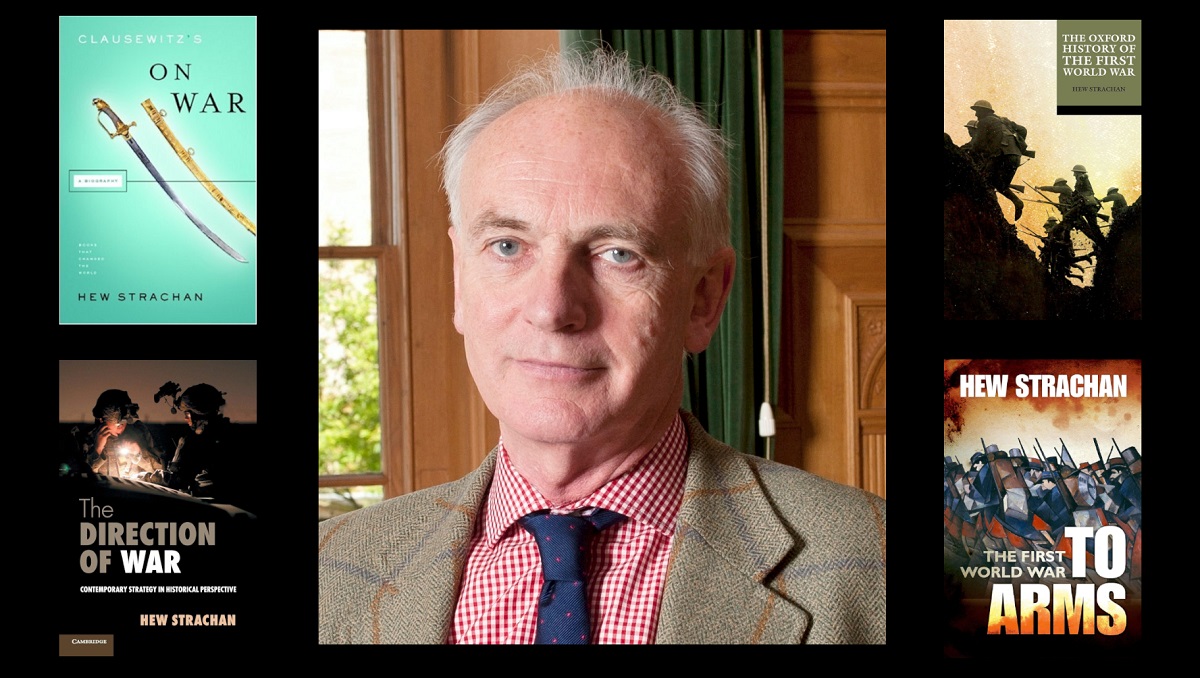

Last week, the U.S. Army War College welcomed Sir Hew Strachan, a distinguished British military historian and accomplished author. He graciously took the time to sit down with Michael Neiberg in the studio for another episode of our “On Writing” series. During their conversation, Sir Hew shared his journey to becoming one of the foremost experts on the First World War. They explored the significance of historical perspective in contemporary analysis, delved into his extensive studies of Clausewitz and other strategists, and discussed how appearing on television prompted him to think about war in more distilled terms. This engaging dialogue showcases the insights of two skilled and passionate historians.

Sometimes I read people quoting Clausewitz and I think, ‘Did he really say that?’ And I look back and yes, he did, he did, and he’s not being misquoted.

Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | Podchaser | Podcast Index | TuneIn | Deezer | Youtube Music | RSS | Subscribe to A Better Peace: The War Room Podcast

Sir Hew Francis Anthony Strachan, CVO, DL, FRSE, FRHistS, FBA is a British military historian, well known for his leadership in scholarly studies of the British Army and the history of the First World War. He is currently professor of international relations at the University of St Andrews.

Michael Neiberg is the Chair of War Studies at the U.S. Army War College.

The views expressed in this presentation are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of The University of St Andrews

Regarding the exceptional benefit that might have been (and, indeed, might still be) derived from our solders and statespersons having access to an accurate and relevant “historical perspective;” as to that such job and exceptional benefit, should our historians, post-the Old Cold War, not have provided (and still provide today) our soldiers and statespersons with a review of history covering the period from the dawn of modern capitalism in the 18th Century up to and including today; wherein, except for the period of the Old Cold War, the political, economic, social and/or value changes demanded by such things as capitalism, markets and trade (and thus not by communism except during the Old Cold War) (a) posed the gravest threat to traditional social values, beliefs and institutions both here at home and there abroad and, thus, (b) were/still are often the “root cause” of conflicts both here at home and there abroad?

Regarding such things as acquiring an accurate and relevant historical perspective, did Clausewitz ever suggest how a state, or a group of states, could and/or should, best use its/their military forces and war; these, to ACHIEVE revolutionary political, economic, social and/or value change — change, for example, so as to provide that the states and societies of the world, to include our own, might be made to better interact with, better provide for and better benefit from such things capitalism, markets and trade?

(“Change” initiatives, thus as suggested in my initial comment above, which posed and still poses one of the gravest threats known to such things as [a] traditional social values, beliefs and institutions both at home and abroad and to [b] those who derive [or wish to derive] their power, influence, control, status, privilege, prestige, safety, security, etc., from same.)

Or has Clausewitz — and his “on war” advice — always come from the PREVENT revolutionary change side of these such conflicts. (His advice, accordingly, being less relevant and useful to our post-Cold War political objective, of ACHIEVING — in the name of capitalism, markets and trade — revolutionary political, economic, change both here at home and there abroad?)

From the beginning of Chapter 24 (The Legacy of the Counter-Revolution; Conservative Ideology and Legitimism in France) of Part IV (The Aftermath and Legacy of the Wars) of the Cambridge History of the Napoleonic Wars:

“Summary:

The French Revolution was the greatest challenge to political authority and social order that the European world had experienced since the Reformation. So confident were the revolutionaries of their vision of the future that they not only wished to refashion politics but sought the regeneration of mankind. They coined the, far from innocent, label of ‘ancien régime’ to consign the past to oblivion. The history of the medieval and early modern world was dismissed as a catalogue of errors, crimes and bigotry. The world was now liberated from the tyrannical forces of tradition and superstition. It did not take long for opposition against this totalising vision of political and social order to coalesce. As Darrin McMahon has stated: ‘the revolution did not need to invent its enemies. They were there from the outset, and their presence exerted a powerful influence on the dynamics of the revolutionary process.’ The counter-revolutionaries of the 1790s were the direct heirs of the counter-enlightenment of the eighteenth century.”

Question — Based on the Above:

As writers, scholars, historians, strategists, etc., go about their duties today, does the above not seem to “rhyme” with our current post-Cold War era; wherein,

a. Those who wish to achieve revolutionary political, economic, social and/or value change universally (in our case today, in the name of such things capitalism, markets and trade),

b. “Did not need to invent (conservative, status quo loving and/or dependent) enemies. They were there from the outset, and their presence exerted a powerful influence on the dynamics of the revolutionary process.”? (Item in parenthesis immediately above is mine. See the last few sentences in the larger quoted item that I provide above.)

Addendum:

The above larger quote comes from Volume III of the Cambridge History of the Napoleonic Wars. Apologies.

Thanks for this podcast, it was engaging. I have to ask a daft question though, sorry. During this conversation, you mention two writers / strategists / theorists on war. Clausewitz is one, but I can’t make out or recognise the name of the other. Please could you post it in this thread so that I can add it to my reading collection?

The other work mentioned is (in English) ‘The Summary of the Art of War’ by Antoine Henri Jomini (1830).