This emphasis on acceptance lacks the transformative appeal and exclusivity of proven recruiting methodologies.

The commercial opens innocently enough with a montage of young, diverse Gen Zers, going about their morning routines as they prepare to start the day. The scenes are marked by a nervous energy which implies this is not a normal day; the haste demonstrated by the actors conveys an air of foreboding. As they say goodbye to their families, in the background a stylized marching cadence grows louder. The young men and women each make their way down a bus aisle, take their seats, and exchange a brief, albeit slightly apprehensive, smile. As the bus nears its destination, soldiers marching in formation are seen through the window. Text makes clear the desired takeaway: “You never know what you’re capable of until you take that first step.” It ends with the widely celebrated tagline “Be All You Can Be” superimposed over soldiers climbing ropes.

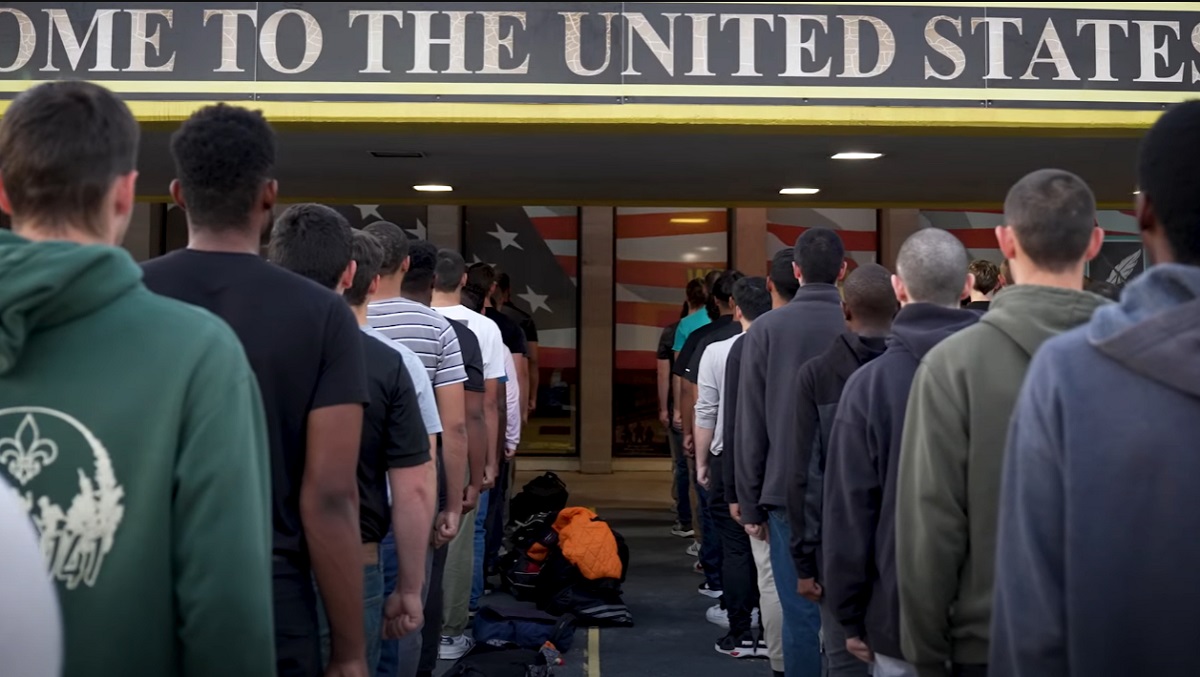

The commercial, titled “First Arrival,” is part of the U.S. Army’s rebranded marketing campaign designed to target Gen Z by reinventing the classic 1980’s recruiting slogan “to reflect today’s Army and country accurately and authentically.” The campaign, which debuted in March 2023, is a key component of the Army’s larger effort to address a decline in recruiting in which it failed to meet its goals for two consecutive years, falling short by 25% in fiscal year (FY) 2022 and nearly 20% in FY2023. Unfortunately, the rebrand is failing to attract the number of recruits the Army needs largely due to how it depicts soldiers in its advertisements. The most striking feature of “First Arrival” and the other commercials in the series is the unremarkable nature of the actors portraying soldiers on screen; they genuinely appear as physically immature and forgivably naïve 18- to 20-year-olds–they are your average high school seniors. Instead of portraying a soldierly archetype that offers a model to aspire towards, the campaign presents its target, Gen Z, with a mirror image of themselves, as they are, and without much of a demand to change. This emphasis on acceptance lacks the transformative appeal and exclusivity of proven recruiting methodologies. The associated effort to blur the cultural distinction between society and the military undermines the importance of the Army as a subculture. Instead of catering to popular norms that promote inclusivity, Army marketing should embrace the unique attributes that make serving in an all-volunteer force exclusive and transformative. While the implicit focus on inclusivity and acceptance is noticeable in the “Be All You Can Be” advertisements, correcting it requires a careful understanding of the marketing strategy behind it.

The Problem

In a pamphlet (GPO 2023-771-642) distributed at the October 2023 Association of the United States Army conference, the Army Enterprise Marketing Office outlined the strategy behind the “Be All You Can Be” brand refresh. Although not couched in a traditional “ends-ways-means” construct, this framework offers a useful heuristic for identifying some of the strategy’s more problematic elements, chiefly its ways and means. The campaign’s end, or objective, is best described as “engaging Gen Z audiences with an aspirational focus on all the ‘Possibilities’ the Army can help actualize.” It is important to note the aspirational focus is on the “possibilities” the Army can provide to the individual, not on the intrinsic value of service to country or the transformative potential this service may offer through the sacrifices it requires. This places Army marketing in competition with private sector campaigns by ceding the moral distinction and inherent exclusivity associated with service in an all-volunteer force for the tangible benefits available from this service. This alone does not negate the strategy’s effectiveness; it simply acknowledges its general approach and position in the market.

The strategy’s “way,” or method, centers on “reinventing it [Be All You Can Be] to reflect today’s Army and country accurately and authentically.” This is manifest in a dedicated effort to blur the distinction between the Army and society, with the governing assumption that the Army should mirror society. Expressed as a culture gap, the strategy identifies certain elements of military service as “out of step with modern culture” and seeks to remedy them by demonstrating that life as a soldier is not all that different from life as a civilian. Unfortunately, those seeking a stimulus for personal change or the opportunity to serve in a unique organization may not find the Army very attractive when what and who they see on screen looks an awful lot like their current environs. Not only is this unappealing, but it betrays a woeful ignorance of the importance of the Army as a subculture.

The culture gap “Be All You Can Be” is attempting to bridge is a purpose-built element of the Army’s identity that distinguishes it from society and enables it to perform its expeditionary warfighting mission. Sanctioned to commit taboo acts–the killing of other humans–the Army is a subculture governed by a unique set of norms, values, traditions, and laws that may seem arcane or even oppressive to outsiders. However, these exist for a reason, as they form the guardrails for an organization trusted with carrying out violence on behalf of the nation. They instill, preserve, and indicate the good order and discipline necessary to prevent excess and to ensure soldiers act in accordance with lawful orders and regulations when operating under duress. As such, soldiers are conditioned to deny a degree of self-expression and embrace uniformity as a method for bringing order to chaos and preventing personal passions from coloring behavior on the battlefield. We have funny haircuts, do not grow beards, wear a uniform, and abstain from certain forms of political expression to name but a few. As unpopular as this might be, it is born out of selflessness and a recognition that our profession requires a degree of self-denial incongruent with the liberties celebrated in the dominant culture. Instead of running from this, Army marketing would be better positioned by embracing the norms, values, and traditions that distinguish the Army from society.

Although not a “means” in the conventional sense, the Army marketing team established two pillars to focus its messaging to “connect with the goals that matter to Gen Z.” The first pillar, “Purpose & Passion,” captures the spirit of the original “Be All You Can Be” campaign by showcasing the Army as a vehicle for finding purpose in life and becoming the best one can be. However, the second pillar, “Community & Connection,” is plagued by an effort to portray the Army as “a place where you are welcomed, understood, and accepted.” Achieving this requires inclusive advertising that dispels the notion of a soldierly archetype by ensuring the actors portraying soldiers on screen and in print are largely unremarkable and indistinguishable from individuals found in an average high school classroom. While unremarkable, they are not uniform, and they retain a degree of individualism to emphasize that everyone is understood and accepted.

Instead of this uninspiring approach, Army marketing should take a careful look at how it can integrate proven elements from other recruiting campaigns to attract the numbers it so desperately needs.

The problem with this is twofold. First, its uninspiring portrayal implies a low bar to entry that lacks the exclusivity many people desire in organizations associated with their identity. People are naturally drawn to special, elite, or exclusive organizations. For example, most high schoolers strive to make the varsity or competitive club team and are proud when they do. Second, the use of the past participle “accepted”–that one is already understood and accepted–negates the transformative appeal of joining the Army to forge a new identity superior to the current one. It dismisses the notion that acceptance is contingent on a transformative crucible or rite of passage and works to convince its target demographic that service neither requires nor inspires change beyond that which is comfortable and agreeable. Instead of this uninspiring approach, Army marketing should take a careful look at how it can integrate proven elements from other recruiting campaigns to attract the numbers it so desperately needs.

Exclusivity Sells

Only two services met their recruiting goals in FY2023: the Space Force and the Marine Corps. The Space Force, the newest and smallest military service, is an outlier, with an overabundance of applicants vying for the branch’s few, highly technical billets–a form of exclusivity in and of itself. The Marine Corps, an established service without the futuristic intrigue associated with cyber and space warfare, had no problem meeting its recruiting target in FY2023. Although many are quick to point to the Marine Corps’ comparatively small size and lower recruiting quotas as the reason for its success, this fails to account for the relatively fewer resources that service receives as compared to the Army. For example, in FY2024, the Army seeks to recruit 55,000 active duty soldiers on a recruiting and advertising budget of approximately $680 million, while the Marine Corps aims to recruit 33,000 on only $246 million. This equates to a cost of approximately $12,363 per potential recruit for the Army and only $7,545 for the Marine Corps. The Marine Corps’ success cannot be dismissed because of its size and must instead be the result of a different marketing approach.

Marine Corps marketing is premised almost entirely on exclusivity, elitism, and the honor associated with earning the title Marine. Potential recruits are not welcomed, understood, and accepted until they prove their mettle and earn that acceptance. Furthermore, instead of downplaying the differences between society and the Marine Corps, recruiters emphasize the service’s mystique and are quick to point out that its unique culture is not for everyone. This overt elitism is the central theme of the recruiting slogan, “The Few. The Proud. The Marines.” It carries through in commercials that highlight the challenges inherent to service and the selfless motives behind the decision to serve. Although extreme, the exclusivity and elitism so prominent in Marine Corps advertising are key features of a successful military recruiting strategy that are woefully absent from the Army’s “Be All You Can Be” campaign.

Similar success stories have emerged not from the services, but from Hollywood. The 1986 film Top Gun boosted Navy recruiting by depicting the Navy’s best pilots, their competitiveness, and the harrowing nature of naval aviation. The film’s success is one reason why the Navy maintains an office dedicated to cooperating with Hollywood on films that serve both their interests. The Army has even gotten in on the action, with films like Black Hawk Down and Saving Private Ryan highlighting unique aspects of military subculture that inspired some to join. The success of these ventures, their willingness to show the military in stark contrast to civilian culture, and the exclusivity this conveys are all factors that Army marketing should consider when evaluating alternatives or modifications to the “Be All You Can Be” campaign. While Army marketing must undoubtedly cast a wide net in its effort to attract a broad cross-section of the country to fill its ranks, it should do so by portraying the Army as the unique institution it is and showcasing the best in its ranks. It should show potential recruits not what they are, but what they can become by featuring sergeants and lieutenants in their prime, leading teams and platoons, training in adverse conditions, winning grueling military competitions, and deploying on behalf of the nation’s interests. It should adjust its strategy to show that while all are welcome, it takes sacrifice, selflessness, and teamwork to earn acceptance. It should take a page from the recruiting efforts of some elite Army units by introducing the exclusivity or intrigue that that naturally appeals to the human psyche. Finally, it should use caution when attempting to depict the Army and society as culturally one and the same. Not only does this lack appeal, but it is also false advertising. If Army marketing is unable to make these adjustments within the thematic confines of “Be All You Can Be,” then it may need a new slogan; one less focused on the individual and better situated to convey the Army ethos and camaraderie that cannot be separated from it: “This We’ll Defend.”

Christopher Parker is an Army strategist and lieutenant colonel currently serving as a strategic planner on the Joint Staff, J-5. He holds a BA from Kansas State University, an MA in History from Georgia Southern University, and is a Ph.D. student in Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Gratz College. He has served combat tours in Iraq.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, the Joint Staff or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Screen capture from You Tube video What Is Day 1 of Basic Training Like? | GOARMY

Photo Credit: U.S. Army Recruiting

Is it possible that Gen Z:

a. Already sees themselves as being in/as having joined a group that is indeed different, elite, unique, special, exclusive, etc.? And, therefore,

b. Seeks to find job opportunities in critical (“vanguard”?) organizations with similar goals as their own; goals such as those noted below:

“We are driven by a desire to create a better world for all, and we are passionate about making positive change in more than just one way. We Want a Future. It’s not just us that we’re fighting for. We have a vested interest in creating a positive and sustainable future for ourselves and future generations.” Gen-Z for Change

(The “marketing” goal, therefore, becomes to clearly and dramatically SHOW the exceptionally critical role — and indeed the “vanguard” role — that the U.S. Army is playing; this, in “creating a better world for all,” in “making positive change in more than just one way” and in “creating a positive and sustainable future for not just Gen Z but for future generations?)

From the perspective that I offer above, “mirror imaging:”

a. Between what both we and Gen Z are “passionate about” — and between what both we and Gen Z are “fighting for” —

b. This such specific “mirror imaging” should be (a) considered to be an exceptionally positive thing and be (b) something that we should definitely use to both our, and Gen Z’s, greatest and fullest advantage?

Great report! The Gen Z all-volunteer force is currently at the Platoon and Company level defending the rule-based order established 79 years ago. They are deploying as much, (or more) to non-combat zones to posture in competition to prevent escalation. Often they are deploying to assure and deter as part of unnamed operations. Whereas their Battalion Commanders (most from the millennial generation) deployed to combat during COIN–Gen Z receive no “combat pay” from their deployments and must consider warfare against peer-competitors. I have great respect for this next “greatest generation.” Their efforts directly contribute to sustaining the American way of life during a test of American power not seen for several decades.

Let’s craft a recruiting campaign that recognizes the weight and honor of that task.

agree on all

To put it bluntly, I think one of the Army’s biggest hurdles to recruitment boils down to choices made by politicians, not by Army marketing.

For starters, I believe it is public perception that the Army is often/mostly used in pointless, unwinnable conflicts that are not aligned with the interests of American citizens. The truth of this perception may be debated, but you only need to look to the YouTube comments on the “First Arrival” video (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y0ayd2k3bTs) to see this sentiment repeated.

To take a quote from this article, I agree that the Army “…should show potential recruits not what they are, but what they can become by featuring sergeants and lieutenants in their prime, leading teams and platoons, training in adverse conditions, winning grueling military competitions, and deploying on behalf of the nation’s interests.” The key issue is that until politicians choose to use the Army more responsibly, no marketing campaign will make the public believe that the Army consistently deploys “…on behalf of the nation’s interests.”

It would be interesting to see how this perception may differ for an organization like the National Guard, which is sometimes portrayed as an organization that helps with disaster recovery—a tangible impact at home.

Another factor is that potential recruits may not believe that they will be taken care of should they be injured while serving. Again, I see this as largely an issue for which politicians are to blame. If the US heathcare system, and VA hospitals are perceived as inadequate or absurdly expensive, folks are going to be less willing to serve. The existence of homeless veterans, while certainly not the majority of veterans, also does not help recruitment efforts. It may come across as ‘selfish’ to those of older generations, but why risk sacrificing your body if your country is unwilling or unable to take care of you afterwards?

Preventing the use of the Army in unwinnable conflicts, improving healthcare access and affordability, and making sure that every veteran is well supported so that homelessness for veterans is eliminated would go a HUGE way towards making it possible for the Army (and military at large) to meet its recruiting goals. Consider it a national defense/recruiting expense if the money needs to be justified.

Regarding my initial two comments above, wherein, I suggested that the (elite?) Gen Z and the (elite?) U.S. Army’s goals might be seen to be aligned/might be seen, generally speaking, as being the same — with our recruiting goals to be more likely to be met if we were to exploit this commonality. (We are both “driven by a desire to create a better world for all”/by “a desire to create a positive and sustainable future for ourselves and future generations” and we are both pursuing such objectives because we are both “passionate about making positive change in more than just one way.” These such things being, in truth, what both “we” and “they” are ultimately “fighting for” — and what American’s, generally speaking, have been fighting for a very long time?)

As to that such thought, however, there is one gargantuan problem today; this being, that both Gen Z and the U.S. Army would seem to be living in what might be called the American Gorbachev Moment; wherein, former President Trump (and those of his ilk) are seen to be abandoning America’s long-standing “desire to create a better world for all,” etc., raison d’etre; this, much as Gorbachev (unintentionally in his case?) abandoned the Soviets/the communists’ long-standing “desire to create a better work for all,” etc., raison d’etre back about 1990.

Thus, if former President Trump prevails in the coming election, and if the U.S. becomes weaker and much more isolated accordingly (exactly as what happened with the Soviets/the communists when their abandoned their raison d’etre back-in-the-day?), then are not both Gen Z, and the U.S. Army’as presently configured, left out in the cold in this process?

Bottom Line Thought — Based on the Above:

When Gorbachev Movement did its thing, cir. 1990, 70 + years of Soviet/communist — hard fought for — power, influence, control, status, privilege, prestige, safety, security, etc., immediately went down the drain.

If the Trump Movement (i.e., America’s Gorbachev Moment) prevails today — and if they do their thing accordingly — then does not the exact same thing happen to the United States? (In our case, however, with the U.S. losing 100 + years of — hard fought for — power, influence, control, status, privilege, prestige, safety, security, etc.?)

If such indeed is the case, then does not this “American Gorbachev Moment” need to be discussed more frequently and more thoroughly today — and not just in the context of what it would do/is doing to Gen Z, and the U.S. Army’s (in)ability to recruit same?

It strikes me as both quintessentially American (and also a bit naïve) to think that, if only we got the marketing right, we would solve this problem. Economics and demographics matter. https://angrystaffofficer.com/2023/12/07/water-is-wet-solving-the-military-recruiting-crisis/

Question — re: your comment above:

Why do economics and demographics seem to matter in the case of the U.S. Army, but not seem to matter in the cases of the U.S. Marines and/or the U.S. Space Force?

B.C., I think I can answer your answer with two words: size matters.

The Marines recruit for a force of 209,600 (both Active and Reserve). Space Force recruits for a force of 8,500. The Army is almost 5 times the size of the Marine Corps and 118 times the size of Space Force.

Now, does this mathematical answer get to the root of the U.S. Army’s struggle with recruitment? No, it does not. Military recruitment is a struggle throughout the west. I believe there are deeper sociological problems at play here.

Very interesting and insightful article. What you say here – and what some of the replies are saying – reflects what many critical thinkers are actually very frustrated about re the Army and its often fossilized and constrained thinking, which is derivative of the hyperconservative, very cognitive-bias-limited, and risk-averse psychology of its members and as an organization. Army and DOD tend to outsource critical thinking even as the intellectual capital to solve / mitigate most of its problems are currently serving, while wearing Army green or DA Civilian attire.

Having spent time as a commander in Army Recruiting, and having spent considerable time studying such issues, your points and those of the commenters are quite on point and are the ‘elephants’ in the room which are being assiduously unaddressed.

This reboot of the brand/slogan, and the prior failed attempts at different ones which would be humorous if they weren’t reflective of failure at implementing motivational psychology and reality, reflects all this and much more.

Either Army did not include motivational psychology and related experts along with marketing consultants when they did this reboot, or the ones they had should not have been on the team, or their input was provided but rejected…as happens so often when intellectualism and informed input runs up against entrenched bureaucracies and stultified minds and cultures.

The recruiting problem can be solved but not how the Army is doing it now, and you and some of the commenters are illustrating some of the reasons why,

Great analysis. Unfortunately we keep trying to solve the problem at recruitment without addressing the underlying division between the military mission and the majority of civilians’ understanding of that mission.

The United States Army’s communication with the public is disjointed. Communication flows to the public along three paths with very different intentions, which creates communication gaps. The Army needs to create a structure to improve its ability to communicate strategically about its mission across all age demographics. Improved communication will increase civilian understanding of the Army mission, structure, and job opportunities.

The Army must create the governance model for a program that not only provides guidance, but also has a methodology to provide messaging, develop metrics for success, and collect information on program effectiveness. The Office of the Chief of Public Affairs (OCPA) is the primary office that should run the governance model of the new program to increase overall awareness of the Army. The program should leverage the Army Enterprise Marketing Program (AEMP), while the AEMP reevaluates how it measures success. The OCPA can use the US Army War College speaker’s program as a framework to incorporate every organization of the Army, to include outlying organizations such as Reserve and National Guard units, Army depots, and US Army Corps of Engineer offices to reach underrepresented areas and establish contacts.

A synchronized communication plan targeting every age demographic executed by all members of the Army will improve the connection between the civilian population and the military, thus increasing positive public perception of the U.S. armed forces. This improved connection will increase the target audience’s propensity to serve and boost recruitment numbers for the U.S. military.

What mood or atmosphere is created by the young Gen Z actors in the commercial?