The nearly uncontested conquest of the town at the center of the novella is thanks in part to a collaborator in their midst, a prominent townsperson who had set the conditions that ensured a smooth entry for the invading force.

Most readers likely associate John Steinbeck with mandatory High School assignments—The Grapes of Wrath, or perhaps Of Mice and Men—and are not aware of his work during the Second World War. Steinbeck served as a war correspondent in England and in Italy, and much of his wartime writing (both fiction and nonfiction) was borne out of his own experiences and observations. One of his lesser known works is his short classic of resilience and civil resistance, The Moon is Down.

Published in 1942, The Moon is Down is set in an unnamed Northern European country, where an invader (with some very thinly veiled similarities to Nazi Germany) rapidly overcomes the people of a mining town and their miniscule local militia. The nearly uncontested conquest of the town at the center of the novella is thanks in part to a collaborator in their midst, a prominent townsperson who had set the conditions that ensured a smooth entry for the invading force. The book does not focus on the invasion however, and contains no battle scenes, but centers rather on how people cope with occupation, and the social dynamics at play within resistance movements.

Shaken by their rapid capitulation and immediate occupation, the townspeople do not know precisely how to interact with their initially benevolent invaders, and are vexed as to how to feel about the new status quo. The town is isolated from the rest of the country, and the local leaders grapple with what the appropriate behavior is for an occupied people. The commanding officer of the invading force, a Colonel Lanser, is obligated by his orders to administer the town through collaborating local authorities. As a result, the mayor is not removed, but remains the face of the local government as Colonel Lanser and his staff attempt to keep the town peaceful and the townspeople docile by governing through familiar leaders. The invaders need the town for its natural resources—particularly coal, and to get it the townspeople must be cooperative with the occupying force.

Colonel Lanser initially has an ironically cordial relationship with the Mayor given the circumstances, until the Mayor finds his courage and begins to assert himself. The emboldened local leader tries to warn the Colonel that the townspeople may not accept their current condition as a lasting one, and reminds Lanser that “the one impossible job is to break a man’s spirit permanently.” Colonel Lanser himself is a semi-tragic figure, torn between his lessons of the last war, and his orders—leading the occupation only grudgingly. He counsels caution to the younger officers, and is a pragmatic if not somewhat melancholy figure. The experienced Colonel expects resentment (“there are no peaceful people” he remembers), and understands that a strong response to resistance or acts of sabotage will only begin a cycle of reprisals and resistance. When one of his officers is killed after trying to force a townsperson to work, the Colonel sees the “spark that can burst into flame” ignite an earnest resistance—“so it begins!” he proclaims.

The dichotomy between the older generation who has seen the human cost of war, and the younger ones, full of faith in their system and their cause, is the most interesting theme of the book.

Slowly, both overt and deniable acts of sabotage slow down progress for the occupiers. The local miners “make mistakes” and machinery breaks, and eventually outside sponsors send dynamite in by parachute to cut the railroad. The occupiers’ reactions to mounting resistance are split between the experienced Colonel, and the naïve younger members of his staff. The dichotomy between the older generation who has seen the human cost of war, and the younger ones, full of faith in their system and their cause, is the most interesting theme of the book. Tensions build as Lanser and his staff lurch into to a familiar historical pattern: the seemingly inevitable cycle of occupation, resistance, and violence.

Steinbeck tells the story of the psychological changes within the town as resistance mounts, as the originally confident conquerors begin to fear the townspeople. Some of Colonel Lanser’s staff begin to lose faith—first in their mission, but then also in their domestic leadership. “Is this place conquered?” asks one of the younger officers of his Captain. When his Captain replies with “Of course,” the doubting Lieutenant begins to unravel: “Conquered and we’re afraid, conquered and we’re surrounded.” His once-total faith shaken, the previously confident Lieutenant observes that they’ve moved “conquest after conquest, deeper and deeper into molasses.” Hysterical, the Lieutenant has a new perspective on the war, and can see new headlines: “Flies conquer the flypaper. Flies capture two hundred miles of new flypaper!”

The Moon is Down is a quick, worthwhile, and timely read. It is not one of dramatic battle scenes, but rather an examination of how the Mayor and the townspeople grapple with what it means to be free, and their obligations as free people and citizens. Criticized as propaganda by some, it is worth noting that the novella was clandestinely printed in or smuggled into multiple occupied countries by 1944, inspiring the will to resist across Europe. After World War II, Steinbeck was even recognized by the Norwegian King due to the perceived impact of The Moon is Down in Norway. It is difficult to read this classic work in 2022, however, and think of Norway, or World War II, but rather of Ukraine. Are there Russian soldiers wondering now if “the flies have captured the flypaper”? Time will tell.

Rick Chersicla is an Army Strategist currently serving in a joint headquarters in Europe.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

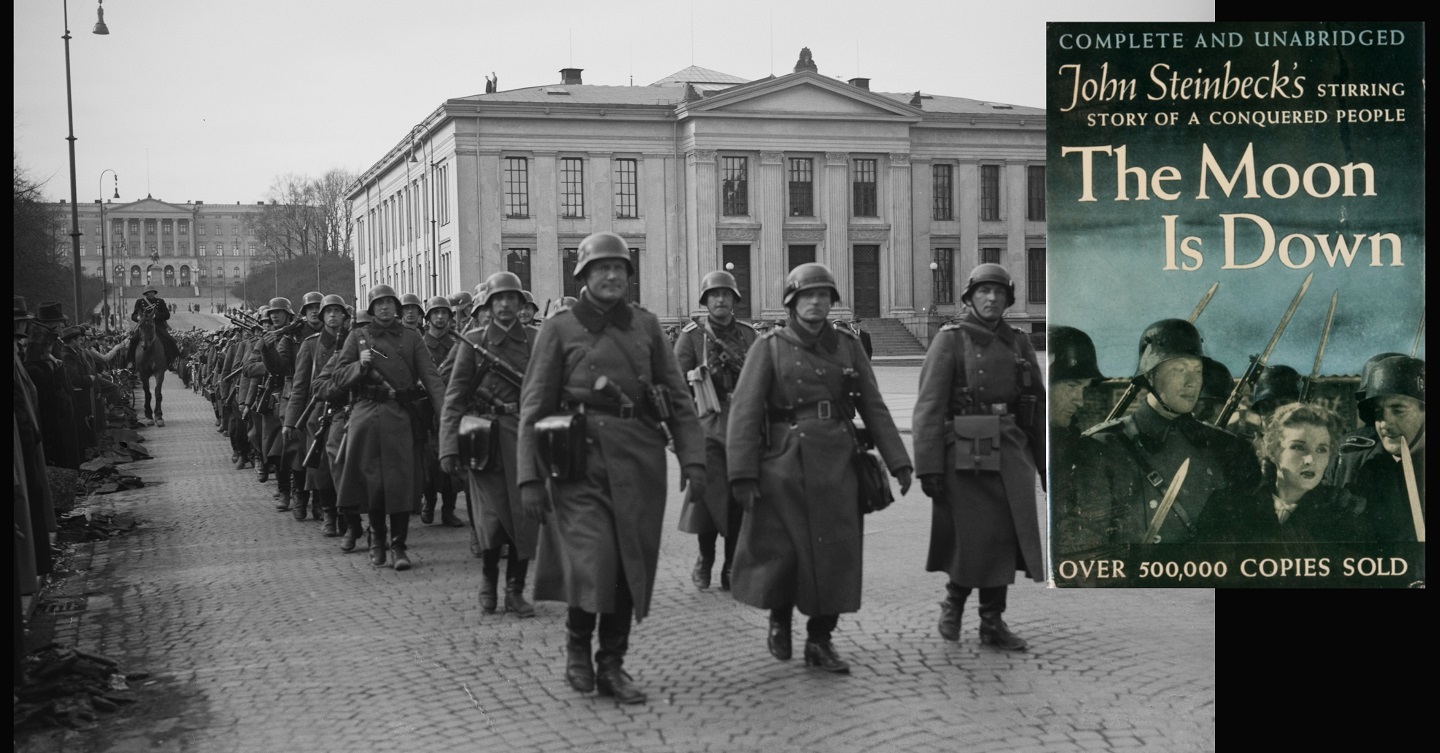

Photo Description: Troops of the Wehrmacht, the military forces of Nazi Germany, in Oslo, Norway on April 9, 1940, the first day of the German invasion and occupation of Norway in World War II. The soldiers are equipped with greatcoats, steel helmets, studded jack boots, Karabiner 98k rifles and field gear. They are marching down the Karl Johans gate Street while civilians have gathered on the pavements as spectactors of the show. Unarmed Norwegian police in dark overcoats and British brodie helmets help maintain law and order. In the background are the Royal palace, the buildings of University of Oslo, etc.

Photo Credit: Henriksen & Steen (Photographers in Oslo, Norway) / National Library of Norway

I like this article! Nobody likes to lose but in the end of a conflict, somebody does.

Conflicts may not be what they seem at the time. In the end Russia and Putin may go down as the heroes.

It might be wise to not automatically jump on every government sponsored narrative. Covid, Vaxxes, “killed by police”, climate change, election fraud, Russia collusion hoax just a few things falling apart before our eyes.

We must consider “resistance” — and “the resistance” I suggest — on a much larger, on a much different and indeed on a much more consequential scale, for example, as per what is noted below:

“Another taboo in Europe is about to be broken. In Sweden, voters delivered a narrow mandate after elections on Sunday to a loose coalition of right-wing parties, including one with a neo-fascist past. On Wednesday evening, Prime Minister Magdalena Andersson, a center-left Social Democrat allied to other left and green parties, conceded defeat. Her party had won 30 percent of the vote — making it still the single largest faction in parliament — but their coalition secured three fewer seats than their rivals to the right.

The kingmakers in Sweden are the far-right Sweden Democrats (SD), a party founded in 1988 by ultranationalist extremists and neo-Nazis. Over the past decade, they have moved from the fringes of their country’s politics into the mainstream. This week, they secured some 20 percent of the Swedish vote, enough to make them the second-largest party in Sweden.”

(See the Sept 16, 2022 Washington Post article “Sweden’s Election Marks a New Far-Right Surge in Europe,” by Ishaan Tharoor.)

In the scenario that I provide above (which is similar to what is occurring on a global scale?), the more conservative populations of the world have come to see — as their “occupiers” — those governments, those individuals, those groups, those businesses, etc. (who, in fact, have been in power since the late 1980s?) who (a) see national security more through the lens of victory on the economic battlefield, who, accordingly, (b) see mastery of such “weapons” as capitalism, globalization and the global economy as their priority and who, thus, (c) require such “revolutionary” political, economic, social and/or value “changes” as are necessary; this, so as to make their such “weapons” both more powerful and more effective.

It is specifically because of these such — status quo/power, influence and control-destroying — “revolutionary changes,” however, that the more conservative elements of the states and societies of the world have now come to be in “resistance” mode.

Bottom Line Question — Based on the Above:

Based on my suggestion above — as to who are the “occupiers” and who are the “resistance” and why — how are the “occupiers,” now, going to be able to deal with the “resistance” — a resistance which (as in “The Moon is Down” example above) is (a) no longer docile and indeed which has (b) now decided to fight back both more actively and more aggressively?

Addendum:

In the second to last paragraph of our article above, the author points to the “psychological changes” that “the occupiers” undergo; this, as “the resistance” mounts.

Based on the suggestion that I make — in my initial comment above — as to who “the occupiers” today might be; as to that this such suggestion, might we say that these “occupiers,” also, may be undergoing such “psychological changes?”

Addendum 2: From the third to last paragraph of our article above: “The dichotomy between the older generation, who has seen the human cost of war, and the younger ones, full of faith in their system and their cause, is the most interesting theme of the book.”

Question: Re: the scenario that I present in my initial comment above — and “the occupiers” that I describe there — re: these such matters, is there a similar dichotomy between (a) the older generation and (b) the younger generation today; this such dichotomy, also, being “the most interesting theme” that we (and especially “the occupiers”) must consider?:

“The report overwhelmingly found that globalization is instrumental in creating the world that millennials want for the future. In fact, the majority of millennials see themselves as ‘global citizens,’ rather than a citizen of one particular country, and view the latter as being outdated.”

(See the Dec 7, 2017 CNBC “Make It” article “Millennials Worldwide Say These 3 Things Will Have the Greatest Impact on Their Future Success,” by Ruth Umoh.)

Based on my B.C. says: September 17, 2022 at 12:18 pm comment immediately above, might we say that the Millennials — these, rather than Generation X and/or the Boomers — are much more enamored with the “we are all global citizens” system and cause?

(This such dichotomy being something that “the resistance” today — to wit: the more conservative elements of the states and societies of the world — should be expected to both “work on” and exploit?)

Given the lack of success that Vladimir Putin has had — re: his (attempted) invasion and occupation of the majority of Ukraine — given these such matters, might we say that these types of (attempted) invasions and occupations — by Putin and/or those of his ilk — these are unlikely to be repeated in the near future?

If this, indeed, is a reasonable consideration, then should we not now move on to consider the much more important — and the much more consequential — SUCCESSFUL Putin-led effort; which was/is, to cause a worldwide resistance to U.S./Western-sponsored ‘revolutionary change” efforts to become manifest:

“In his annual appeal to the Federal Assembly in December 2013, Putin formulated this ‘independent path’ ideology by contrasting Russia’s ‘traditional values’ with the liberal values of the West. He said: ‘We know that there are more and more people in the world who support our position on defending traditional values that have made up the spiritual and moral foundation of civilization in every nation for thousands of years: the values of traditional families, real human life, including religious life, not just material existence but also spirituality, the values of humanism and global diversity.’ He proclaimed that Russia would defend and advance these traditional values in order to ‘prevent movement backward and downward, into chaotic darkness and a return to a primitive state.’ ”

(See the Wilson Center publication “Kennan Cable No. 53” and, therein, the article “Russia’s Traditional Values and Domestic Violence,” by Olimpiada Usanova, dated 1 June 2020.)

“Liberal democratic societies have, in the past few decades, undergone a series of revolutionary changes in their social and political life, which are not to the taste of all their citizens. For many of those, who might be called social conservatives, Russia has become a more agreeable society, at least in principle, than those they live in. Communist Westerners used to speak of the Soviet Union as the pioneer society of a brighter future for all. Now, the rightwing nationalists of Europe and North America admire Russia and its leader for cleaving to the past.”

(See “The American Interest” article “The Reality of Russian Soft Power” by John Lloyd and Daria Litinova.)

“Compounding it all, Russia’s dictator has achieved all of this while creating sympathy in elements of the Right that mirrors the sympathy the Soviet Union achieved in elements of the Left. In other words, Putin is expanding Russian power and influence while mounting a cultural critique that resonates with some American audiences, casting himself as a defender of Christian civilization against Islam and the godless, decadent West.”

(See the “National Review” item entitled: “How Russia Wins” by David French.)

Bottom Line Question — Based on the Above:

As to matters more or less important, Putin’s “winning” trend — as evidenced by the recent election results in Sweden and elsewhere (the “main event?;” see my initial comment above) — these cause Putin’s “losing” trend — in Ukraine (the “side-show?”) — to be considered — in comparison — as something less-important — and as something less-significant?

(Thus, before its too late, time to concentrate, again, on where WE — the U.S./the West — are losing?)

Let me attempt to combine certain matters that I addressed — in our “All Invaded People Want to Resist: Steinbeck’s ‘The Moon is Down’ ” article above — this, with certain matters that I addressed in the previous War Room Blog thread, to wit: “Recruiting Woes: A Case of Self-Sabotage.” Here goes:

a. If the conservative elements of the states and societies of the world (who are now in more active “resistance” mode); if these folks believe that they have been “invaded” by progressive/modernizing/development- oriented entities — who see the world more in “pro-globalization”/”we are all global citizens” terms (in this regard, see my B.C. says: September 17, 2022 at 12:18 pm comment above),

b. Then why would these such conservative elements wish to join military organizations whose job — both there abroad and here at home (this latter, if posse comitatus was overturned) — is to DEFEAT these such conservative elements — who now stand in the way of these such “pro-globalization”/these such “development” efforts?

(Note: Should you believe that — there abroad for example — U.S./Western militaries ARE NOT NOW engaged in these such “pro-globalization”/these such “development” tasks, then consider the following from our very own Joint Publication 3-22, “Foreign Internal Defense;” therein, see Chapter II, “Internal Defense and Development Program,” and Paragraph 2, “Construct:”

“a. An IDAD [Internal Defense and Development] program integrates security force and civilian actions into a coherent, comprehensive effort. Security force actions provide a level of internal security that permits and supports growth through balanced development. This development requires change to meet the needs of vulnerable groups of people. This change may, in turn, promote unrest in the society. The strategy, therefore, includes measures to maintain conditions under which orderly development can take place.” [Item in brackets above is mine.])

Bottom Line Thought — Based on the Above:

As it has become more clear to the general public, that the role of U.S./Western military forces today, this is to (a) promote such things as capitalism, globalization and the global economy and thus to (b) stand hard against those who would stand in the way of these such “pro-globalization”/”we are citizens of the world” initiatives; as this has become more clear, the more conservative/the more status quo-dependent elements of the states and societies of the world, these folks, quite understandably, have become less inclined to join/enlist?

True heroism is the courage to resist not only the occupation of your land by an invader but also apartheid, torture, and extermination from your own land. When your only choices are to resist or die, you will choose to resist.

Israel has been committing genocide of Palestinians for 75 years. IOF are the Nazis, the Palestinian Authority is the collaborators, and Palestinians are the ones being exterminated.

As Anthony Bourdaine said, “Today, nearly everything is made in China. Except for courage. Courage is made in Palestine.”

Long live resistance.