Once size has not fit all situations.

The historical record does not offer any cookie-cutter solutions for how the Army should deal with pandemics; no approach has been perfect or will be perfect. Army leaders have had to weigh both current missions and the wider cultural determination of what health risks are acceptable against the specific medical risks the force is facing at a particular time and the available and mitigation methods.

The Army has operated through different pandemics, weighing the risks in each and changing its responses. This essay does not look at medical treatments (which, by definition in a pandemic) are always limited and lagging. However, there are techniques from preventive medicine that can be implemented as command responses to protect the force, albeit at varying costs in reduced readiness and operational tempo. Restrictive measures such as stopping recruiting, quarantining (or at least limiting access to) posts, pausing or stopping troop movements, suspending training, and dispersing troops all reduce the spread of disease – but they all reduce readiness or combat power.

Once size has not fit all situations. Circumstances in 1918 and 1968 were similar (large forces were engaged in wars) and different (by 1968 the influenza virus had been identified and a vaccine developed) so command decisions to balance risk from the pandemic against operational risk ended up being appropriate but also different. The 2020 COVID pandemic was a different situation again, and whatever happens the next time will have its own factors to weigh.

1918 – Winning the war trumps medical advice

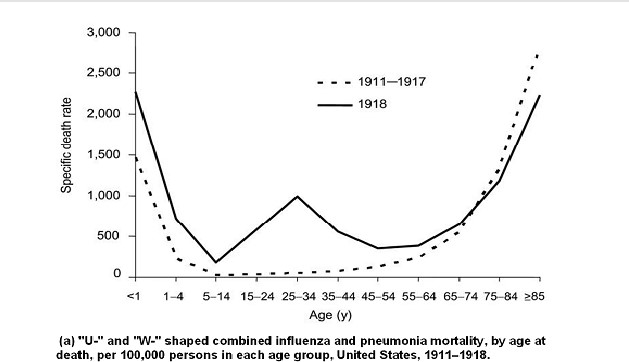

In 1918 the world faced an influenza pandemic that spread like wildfire and was deadliest among the military-age population. (This is termed a W-shaped curve, with mortality peaks among young, old, and – critically – healthy adults, while most epidemic diseases cause a U-shaped curve with deaths clustered in the young and old.)

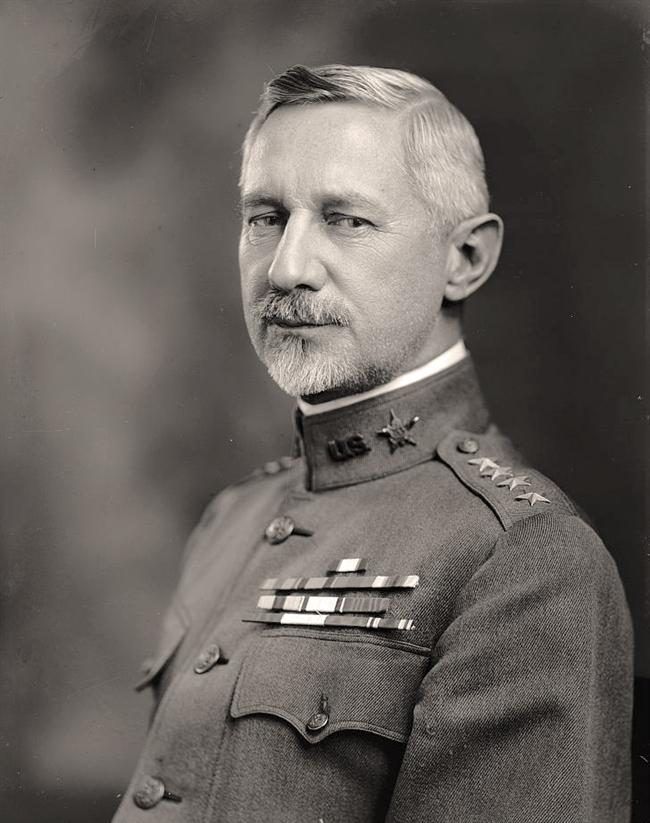

In August and September, while the lethal mutation of the virus was spreading in the U.S., the Allies were engaged in massive offensives in Europe, including the major American efforts at St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne. Reducing the flow of troops would risk undermining those offensives, American influence in Allied negotiations, and American clout at peace negotiations if the U.S. pulled its punches. In late August, immediately upon news of the lethal flu variant at an Army base, The Surgeon General took action. He warned hospitals around the Army, and recommended stop-move orders to Chief of Staff Peyton March.

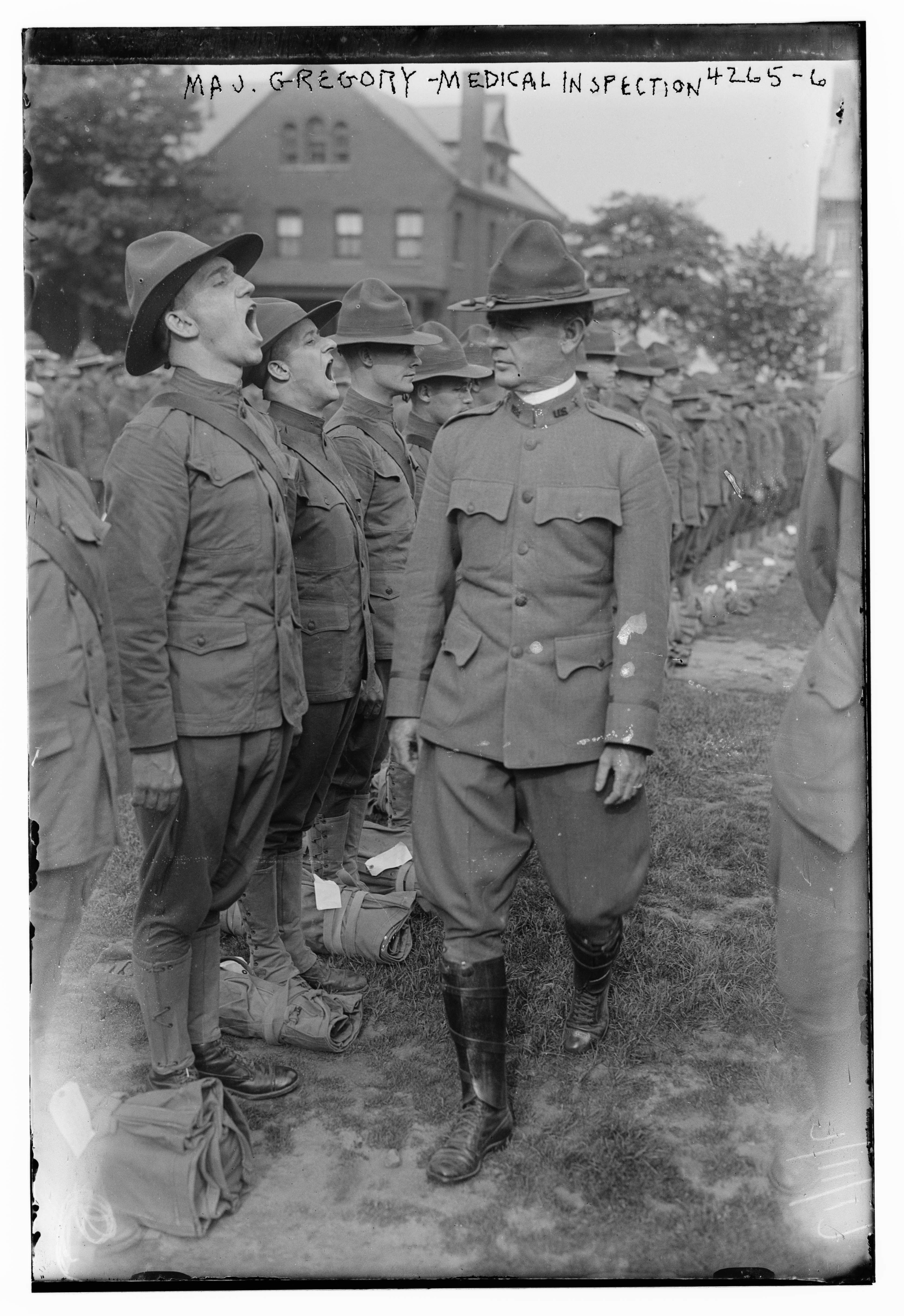

March considered the advice, but rejected it, accepting that Army actions would result in the pandemic spreading, killing more soldiers and civilians. (In 1917 the Army had rejected similar medical advice to reduce crowding in barracks and reduce the spread of disease: “The purpose of mobilization is to convert civilians into trained soldiers as quickly as possible and not to make a demonstration in preventive medicine.”) The disease spread rapidly across the U.S. throughout September. It did not help that science could not yet identify viruses, only bacteria, and thus they could not be sure exactly what was spreading or how it spread.

Late September and early October saw the fastest influenza increase in the Army: about 80,000 influenza infections in the week from 28 September to 4 October, and another 89,000 the following week, right in the heart of the Meuse-Argonne campaign. Medical advice was to halve the loading on troopships for the two-week voyage to Europe, and have troops spend a week at embarkation camps before boarding to identify the sick. GEN March over-ruled that, and was called to see President Woodrow Wilson on 7 October to explain the Army’s response. He ran through the costs of slowing the pace of troop shipments and the list of mitigations (mostly ineffective) that were being done. President Wilson accepted March’s judgment.

But at the same time the situation was changing: multiple Allied attacks were reinforcing each other and forced Germany to ask for an armistice on 5 October. The Army’s response to the pandemic soon changed: draft call-ups were reduced and delayed (although not stopped) to reduce both crowding in training camps and the pressure on Army hospitals. Various ‘social distancing’ techniques were used, both off-duty and on-duty including reducing training, keeping troops on post, closing posts to visitors, suspending church services, and other measures to avoid crowding.

The Army lost some 50,000 men to influenza in WWI, and that number is probably somewhat higher because of GEN March’s decisions. However, he could not know how soon the fighting would be over, and if battle had continued into 1919, the U.S. would likely have lost more battle casualties than those extra disease deaths. Winning the war was President Woodrow Wilson’s priority, and March followed his commander’s intent, including receiving direct assent. With hindsight, March’s actions – doing nothing – caused more deaths, but from the information GEN March had, it was the better choice, and once the operational pressures eased, he allowed more disease-mitigating moves.

In the 1940s influenza vaccine was developed, and compulsorily administered to troops during WWII.

1968 – Doctors say not to worry

In July 1968 a different influenza pandemic started in China, coming to the wider world through Hong Kong. In the 1930s new technologies had allowed the identification of viruses, and identification of different strains of influenza virus. In the 1940s influenza vaccine was developed, and compulsorily administered to troops during WWII. In the 1950s and early 1960s a number of new vaccines were developed, famously including the polio vaccines but also measles, with mumps and rubella under development.

In the summer of 1968 the Army promptly learned of the “Hong Kong flu” outbreak and the Armed Forces Epidemiology Board considered what action to take. Soldiers were a young and healthy population. The new flu was H3N2, somewhat similar to a mild pandemic of H2N2 influenza in 1957, and the N2 similarity might give some protection. There were six domestic vaccine companies to try different approaches and likely produce an effective vaccine quickly. The decision was to take no immediate action, but rely on a vaccine. If the expectations were faulty and there was a W-shaped epidemic instead of a U-shaped one the military had a large hospital system, mitigating that risk.

Thus recruiting and draft call-ups were not slowed, and training, worldwide movements, and operations were not interrupted. The fighting in Vietnam increased, with the second half of 1968 seeing heavy fighting in central and northern areas, and a renewed Tet offensive in February 1969, a year that would be America’s bloodiest year in Vietnam – but not from the pandemic.

The pandemic was essentially ignored in Vietnam, even R&R leave from Vietnam to Hong Kong was not stopped, while troop redeployment from Vietnam back to the U.S. likely helped spread the virus. Rotating troops to U.S. Army Europe (USAREUR) may have sped the arrival of the virus in Germany. Posts in the U.S. took little notice of the pandemic, less than some civilian institutions. For instance, some colleges sent students home, and some hospitals limited visitors. USAREUR did not even mention the pandemic in their annual report.

The calculated risks paid off. At its worst, the 1968 pandemic seems to have sickened 1-2% of troops and had them off-duty for only a few days. The annual influenza vaccine campaign seems to have been pushed harder, and was mandatory for active-duty troops. By November (only four months after the pandemic was identified) there were 1,000,000 H3N2 vaccine doses available, and by January 1969 doses were arriving in Vietnam. The Army had a somewhat higher rate of influenza cases during 1968-69, but it did not affect combat operations in Vietnam or deterrence in Europe. In the U.S. the whole Fourth Army area (stretching from Fort Polk to Fort Bliss, and as far north as Fort Sill) had no confirmed H3N2 cases through December.

Doing nothing was the right answer. The pandemic infected few troops and was not severe when it did. It was not the Army’s first influenza pandemic, and that doubtless helped assess the threat and accept the risks of taking no immediate countermeasures.

2020 – Protecting the force

In 2020-21 the Army has faced a different situation, where the virulence and effects of the virus were both unknown. Meanwhile, safety had become incorporated into Army activities, with accidents damaging commanders’ careers. Previously there was also less emphasis in the nation or the Army on safety. For example, 1968 was the year new cars had to have seatbelts (although wearing them was optional), while the Occupational Safety and Health Act was not passed until 1971. In 1968 the Army safety program was only covering aviation accidents, becoming the Army Safety Center in 1978. If the term “protecting the force” was used, it was understood differently.

In 2020, a focus on protecting the force (including protecting military families and the civilian workforce) caused no particular harm to national interests. Few troops were deployed, and fewer in combat. Recruiting, training, and travel could be restricted in different ways at different times; personal protective equipment could be issued; facilities could be modified to mitigate spread of the virus within the force and the workforce. With only moderate operational requirements, force health protection could be prioritized. At times the government’s messages about health risks were muddled, but the preventive medicine community was trained in health risk communication, and trying to work within overall guidance. Meanwhile, the Army had been an all-volunteer force for almost 50 years, and had spent years talking about how the individual soldier was the most important weapon, how families were keys to retention, and how important the civilian workforce was. Since medicine had advanced so that far more people were immune-compromised or had other identified risk factors, protecting this much more varied group added complexities to what responses were expected.

Conclusion – no easy answers

To conclude, the Army has faced wartime pandemics from known and unknown threats. Medical advice has played a role, but there was a time Army leadership felt it appropriate to accept the certainty of more sickness and more deaths to reduce risks on the battlefield. There was a time doctors advised to take no action. And the most recent example was different again, focused on protecting the force, and protecting military families and the civilian workforce.

None of these examples may be appropriate in future pandemics. History does not provide a cookie-cutter solution, but instead examples of the Army being pragmatic. In the future, Army leaders will have to weigh the missions, medical risks, and mitigation methods. The Army may have to educate officers, soldiers, and the public why it is not making force protection the top priority in a society with a lower tolerance for risk. Leaders having to change the balance in “mission first – people always” will have to communicate that to troops, families, and political leadership in a world linked by social media.

Dr. Sanders Marble is the Senior Historian at the Army Medical Department Center of History & Heritage.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

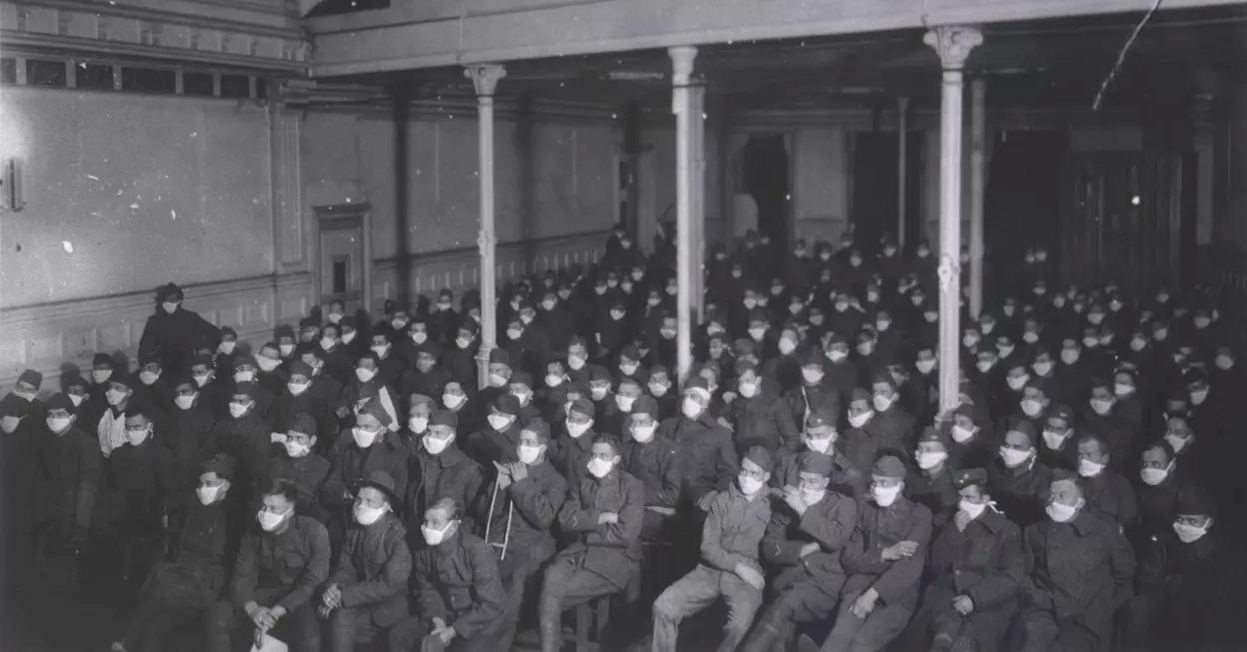

Photo Description: During the 1918 Spanish Flu Pandemic U. S. Army Hospital Number 30, Royat, France. Patients at moving picture show wearing masks because of an influenza epidemic.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the History of Medicine (National Library of Medicine)

Is it possible that our viewing of these matters through a larger aperture might prove useful? Thus:

a. Not so much as per “Pandemics and the Army” alone. But, rather,

b. More as per “Pandemics and United States National Security” in general, for example, as addressed by Colonel (Retired) Robert E. Hamilton here?

https://www.fpri.org/article/2020/07/covid-19-and-pandemics-the-greatest-national-security-threat-of-2020-and-beyond/

I don’t agree w/ J.D. Vance, that’s woosy talk. We have to step up and take the initiative against drugs and foreign advance of dictatorship.