Few other generals better describe how best to translate strategic guidance into an operational approach.

General Matthew Ridgway may be the best fighting U.S. general we hardly talk about. He jumped in nearly every airborne mission in the European and Mediterranean Theaters of Operations, he led the 82nd Airborne Division and the XVIII Airborne Corps through the European campaigns. Later, he stopped the retreat of United Nations (UN) forces in Korea, reenergizing them after a surprise defeat by the Chinese. He would then lead at the highest levels as the Supreme Allied Commander, Europe, and Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army. In retirement, he was recruited to the “Wise Men” and advised Eisenhower and Johnson against intervention in South Vietnam. But few armchair historians would count him in a list of the great military leaders in American history.

It is hard to understand why. Few other generals better describe how best to translate strategic guidance into an operational approach. His The Korean War (1967) ranks among the best personal accounts of operational-level combat command, in large part because Ridgway’s account describes dealing with something almost unthinkable in today’s U.S. Army: defeat. Granted, several generals have written about Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan, but none have had to contend with the operational defeat and forced retreat of an American army in the face of an adversary who not only achieved surprise at each level of war but was armed by a partner (here, the Soviet Union) to the point where it achieved localized operational parity. Much to Ridgway’s credit, he turned around operational defeat and achieved his strategic objectives, all the while building a resilient force capable of regaining the initiative. For an Army facing the prospect of a potential conflict against not one but two near-peer adversaries for the first time in a generation, it is high time we blew the dust of Ridgway’s The Korean War and revisited warfighting at the operational and theater levels.

Thrust into command of the Eighth Army by the accidental death of Lieutenant General Walton Walker days before Christmas 1950—the Chief of Staff of the Army found him sipping a highball at a friend’s Christmas Party when he delivered the news—Ridgway embarked on a whirlwind assumption of command. Arriving in Japan, he conferred with General Douglas MacArthur, the commander of US Far East Command, prior to reporting to the Eighth Army and the UN Command on the Korean peninsula. Reeling from China’s attack across the Yalu River and freezing due to problems with the distribution of cold weather gear, Ridgway’s new command seemed little ready to meet the requirements that the Commander, Far East Command had for it. MacArthur relayed his belief that they were operating within a “mission vacuum” and that a “military success would strengthen our diplomacy.” Given the dire circumstances and the newness of the command, Ridgway still felt confident enough to ask, “If I find the situation to my liking, would you have any objections to my attacking?” MacArthur replied, “The Eighth Army is yours, Matt. Do what you think best” (82-83).

It would be easy to see these lines as the bravado of an old warrior, yet that was not Ridgway’s style. Charged to hold South Korea and maintain its sovereignty, Ridgway surveyed the battlefield and the remnants of the US and UN forces. His writing conveys the defeat in the eyes of these forces: “Every command post I visited gave me the same sense of lost confidence and lack of spirit. The leaders, from sergeant on up, seemed unresponsive, reluctant to answer my questions. Even their gripes had to be dragged out of them and information was provided glumly, without the alertness of men whose spirits are high” (87). It was not the fault of the fighting men, Ridgway argued, but of their leadership. He spoke out against failures in tactical, operational, and strategic leadership. He reached from within the Eighth Army and back to the United States to find capable combat leaders. He traveled throughout the still-dynamic front line, charging commanders with holding the line and regaining the initiative.

This would prove no easy task. The state of Eighth Army and the UN Command as a fighting force, even benefiting from overwhelming firepower and near-air and -sea superiority, was atrocious. “What I told the field commanders,” he recounted, “was that their infantry ancestors would roll over in their graves could they see how road-bound the army was, how often it forgot to seize the high ground along its route, how it failed to seek and maintain contact in its front, how little it knows of the terrain and how seldom it took advantage of it, how reluctant it was to get off its bloody wheels and put shoe leather to the earth, to get into the hills and among the scrub and meet the enemy where he lived” (88-89). As Eighth Army gradually slowed its retrograde south, Ridgway pulled formations from the line to have them refit and execute combat-specific training. The training not only prepared formations to regain the offensive but also built unit cohesion that had fractured in the face of China’s overwhelming ground assault. “Good training,” he stated, “should help a soldier get rid of that awful sense of alone-ness that can sometimes overtake a man in battle, the feeling that nobody gives a damn about him, and that he has only his own resources to depend on” (97).

More important, Ridgway used the next several months to develop a new operational approach that better aligned with MacArthur and Washington’s strategic guidance. In re-establishing a defense south of the Han River, Ridgway optimized the terrain to shrink his front line, form a defense in depth, and rebuild shattered formations. Always with one eye on regaining the offensive, he ensured that he retained the necessary flexibility to seize the initiative. By February 1951, Ridgway turned Eighth Army loose on the Chinese and North Korean armies, but now in a far different manner than several months prior. Formations moved forward deliberately, focusing on seizing terrain only when it “might facilitate destruction of enemy forces and the protection of our own” (108). Ridgway sought to defeat his adversary through a campaign of attrition, leveraging the United States’ asymmetric strength in artillery and air power to decimate enemy forces dislocated by Eighth Army’s assault. With this approach, Eighth Army and UN Command retook Seoul, recrossed the 38th Parallel, broke the Chinese/North Korean Spring 1951 Offensive, and set the military conditions for the warring sides to come to the armistice table.

Ridgway’s attrition approach represented more than just killing the enemy. It demonstrated an adept understanding of the strategic guidance he had been given, the capabilities and capacity at his disposal, and the weaknesses within the enemy to his front. His deliberate attack up the peninsula was intended to coerce the Chinese and the North Koreans towards the armistice table, not to force them across the Yalu. Always with one eye on the threat of regional and global escalation, Ridgway’s metered and dogged approach destroyed Chinese and North Korean formations while ensuring that the war stayed contained within the Korean peninsula. Unlike the other generals who would lead Eighth Army or the Far East Command before and after him, Ridgway maintained military pressure on the Chinese and North Koreans during 1951 without advocating for escalation outside of the peninsula.

MacArthur’s figure looms large throughout the first half of the book; Ridgway looked up to him.

This approach ensured that Ridgway would replace MacArthur after the old general was relieved of command. MacArthur looms large throughout the first half of the book; Ridgway looked up to him. He wrote of the “force of his personality” and how “lucid and penetrating were his explanations and analyses” (81). But Ridgway still saw fit to admonish the elder general’s hubris as he recounts his own anger at the defeat of American and coalition forces near the Yalu during November 1950. His rendering of the Truman-MacArthur split and, more importantly, the role of the military leader with the president, should close the case on whatever is left of the debate about the relief of MacArthur. “It was MacArthur’s privilege, and his duty,” Ridgway wrote, “to give his views as to the rightness of a contemplated course, and to offer his own recommendations, before the decision was rendered. It was neither his privilege nor his duty to take issue with the President’s decision after it had been made known to him” (153).

Even still, Ridgway’s chapter focusing on MacArthur’s relief could be titled “The Death of our Heroes.” He idolized MacArthur, calling him “this great soldier-statesmen” (159). But he knew a line had been crossed. MacArthur’s public rancor and politicking were not fit for this new era of war under the atomic shadow: “We had finally come to realize that military victory was not what it had been in the past—that it might even elude us forever if the means we used to achieve it brought wholesale devastation to the world or led us down the road of international immorality past the point of no return” (231). The palpable shirt-rending that Ridgway conveys as he deliberates over the scene of his military idol boarding a plane for the end of his career should give current Army leaders pause. He makes clear to point out MacArthur’s “lack of rancor and resentment” and how he “seemed to have accepted the decision with better grace…than most men similarly situated” (158).

No matter his feelings for the man, Ridgway remained clear in his convictions: “In their [Joint Chiefs of Staff] view, the kind of ‘victory’ sought by the Theater Commander [MacArthur]…would have incurred overbalancing liabilities elsewhere. It was their duty to advise the President, which they did. It was his turn to decide, and he made the decision” (149).” The policy-operations mismatch of the twenty years after 9/11 is real and deserves to be studied, assessed, and picked apart. In a world of nuclear-powered near-peer rivalry, Ridgway’s clear-eyed appreciation of what could and could not be done should be our guide.

Ridgway knew the stakes in a nuclear-armed world were higher, and he worried many of the same worries he had in 1951 as he wrote in 1967. By the end of The Korean War, it is clear that Ridgway was writing as much about the war in Vietnam as he was about the war in Korea. Having advised the White House privately, he took to his pen to caution readers about how the war in Southeast Asia sapped American strength over a peripheral interest. While stating early that he was not privy to the full breadth of intelligence used to justify the intensification of the conflict, nor seeking to question the actions of those decision-makers in the field or in Washington, he still felt a moral conviction to voice his concern. As he closed The Korean War, he stated “[W]e should ask ourselves now if we are not, in this open-ended conflict, so impairing our strength through overdrawing on our resources…as to find ourselves unduly weakened when we need to meet new challenges in other more vital areas of the world” (250). Ridgway’s thoughts on strategy and prioritization ring truer today than in 1967. Engaged globally, the United States faces myriad crises that each require portions of finite attention and resources. The ability to understand the importance of some interests over others remains as critical now as it was then. For all the discussion of strategy and operational art, civil-military relations and reckoning American power, Ridgway still shines through as a soldier’s general. Recounting one of his many tours of the frozen Korean battlefield during January 1951, he told how, during World War II, he always lost one of his gloves while on the march. Seeing frozen soldiers rubbing their hands together to stay warm, Ridgway decided to bring bags of gloves with him, passing out a pair whenever he saw someone with bare hands. This little anecdote, much like his recounting the pleasure of a warm camp stove, seems trivial if not conveyed with the right voice. For Ridgway, someone capable of navigating the intricacies of each level of war in a page, it is defining: he understood that no matter how great the strategy, or how overwhelming the operation, the objectives would be seized by cold and tired soldiers trying to stay warm. This may be Ridgway’s final lesson from The Korean War: leaders at each level must strive to match the sacrifices we expect daily from soldiers and their families. What rang true amidst the windblown mountains of Korea resonates through to today.

Andrew Forney is a colonel and Strategist in the U.S. Army. He has taught American history at West Point and worked strategic issues at multiple levels within the U.S. Army, to include several deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. Prior to his current assignment at the XVIII Airborne Corps, Andy served as the senior Army strategic advisor to the strategy team within the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Policy. While there, he served as the chief of staff for the 2023 National Defense Strategy review, helping to develop key elements of the strategy relating to integrated deterrence and campaigning.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

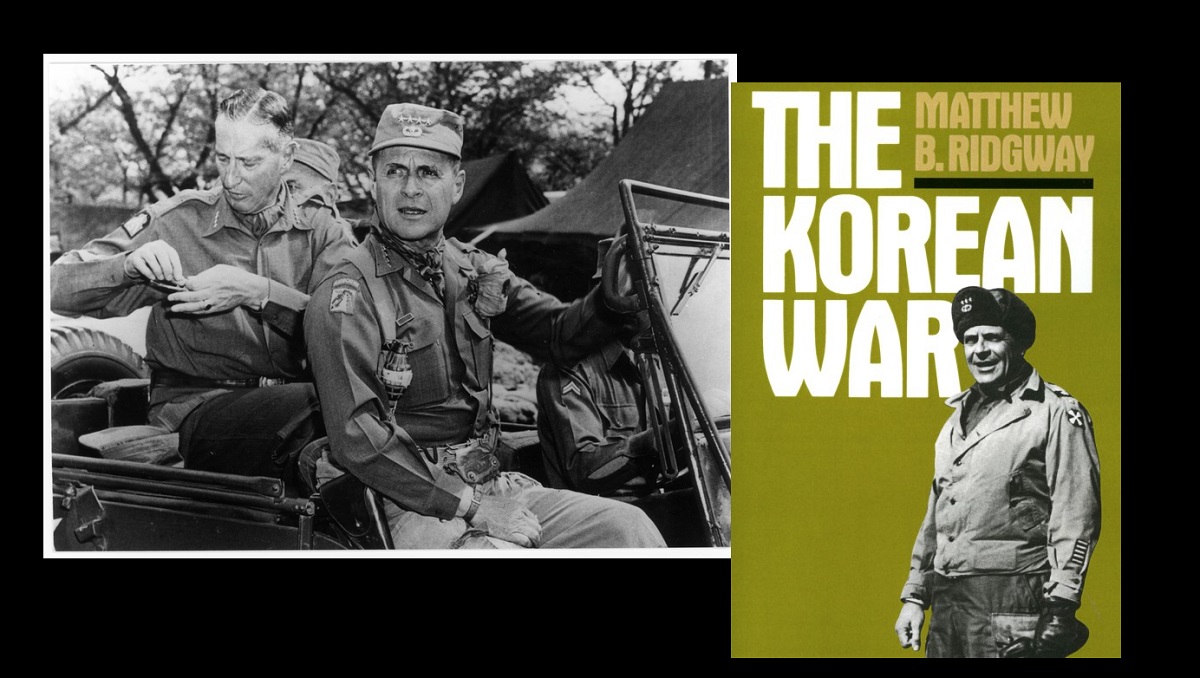

Photo Description: General Mark W. Clark (back seat) and General Matthew B. Ridgway (front seat, foreground) are sitting in a vehicle in Korea circa 1951.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of George Putnam, via Harry S. Truman Library & Museum

This is a fantastic read and highlights some incredibly important lessons in leadership particularly in adverse or turnaround situations. Bravo and well played.

The Korean War is rife with military lessons from leadership to tactical genius at Inchon.

One could mine the Korean War for these lessons and spend a couple of years learning valuable lessons.

1. America’s unpreparedness for war after the WWII victory and letting the occupying troops in Japan get soft and lazy.

2. Gigantic intel failure.

3. Failure to arm our new South Korean ally for the real threat.

4. The fighting withdrawal and breakout from Pusan.

5. The brilliance of the Inchon landing and the following exploitation of cutting the enemy’s supply lines.

6. The race to the Yalu and the folly of sending the 1st Mar Div and Army units up a single lane supply road to the Chosin Reservoir.

7. The brilliant fighting retreat of the 1st Mar Div and the best division commander ever produced by the US.

8. The intel failure of the Chinese intervention.

9. The failure to take the win when it was available and pressing on recklessly.

10. The ability to fight in devastating winter conditions.

I could go on, but I won’t.

Ridgway was a paratrooper and paratroopers are used to fighting whilst surrounded. Gen Troy Middleton knew this and that was why he asked Eisenhower for the 101st Abn when he was tasked to hold Bastogne.

Great column. Thank you.