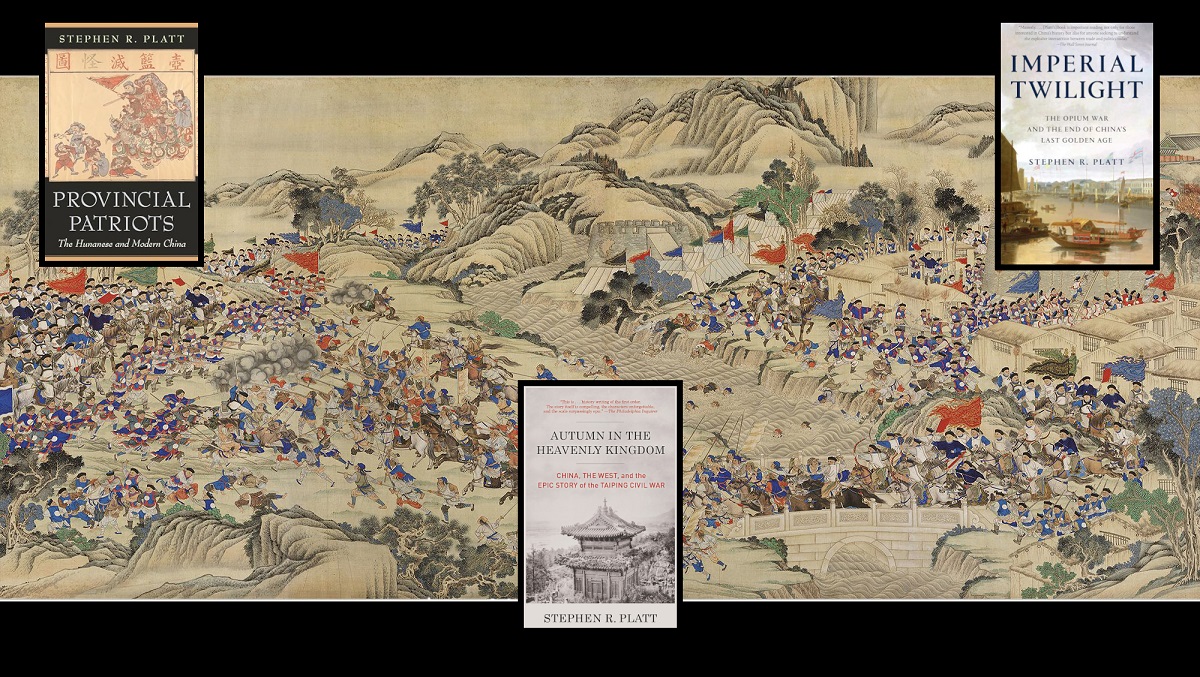

Understanding the history, or perhaps more importantly, the treatment of history in China, is a critical skill for anyone seeking greater comprehension of the national security arena. Stephen Platt has spent a great deal of his career as a historian and author studying events like the Taiping Civil War and the Opium War in the nineteenth century. During his time researching these topics, he acquired an excellent understanding of culture and history in China, as seen by both the people and the government of China. And now he’s in the studio with host Michael Neiberg for another episode in our On Writing series. Their conversation covers Stephen’s books Imperial Twilight and Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom and how the perception of both historic events and their participants has changed over time in China.

Kids in China in the 1950s and ’60s up through the ’70s learned that the Taiping rebels were the great heroes of that era… Then you get to a point in the ’80s where you have a Communist party in China that is no longer revolutionary in any way and does not want to encourage any more revolutionaries, and they turn it on its head.

Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | Podchaser | Podcast Index | TuneIn | Deezer | Youtube Music | RSS | Subscribe to A Better Peace: The War Room Podcast

Stephen R. Platt is a historian of modern China. He is a professor at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and holds a PhD in history from Yale University, where his dissertation won the Theron Rockwell Field Prize. A fellow of the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations’ Public Intellectuals Program, he seeks to engage the wider public in deeper issues of China’s history and its relations with the West. His newest book is Imperial Twilight (2018), a history of the long-term origins of the Opium War. His previous book, Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom (2012), was a Washington Post notable book and won the Cundill History Prize.

Michael Neiberg is the Chair of War Studies at the U.S. Army War College.

The views expressed in this presentation are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

Photo Description: A scene of the Taiping Rebellion, 1850-1864, The Regaining of Jiangpu and Pukou

Photo Credit: Painting by Qingkuan

As to understanding Chinese history — or perhaps more importantly the treatment of history in China — might the following prove useful? This is from the concluding paragraph of the 2015 Foreign Policy paper “What it Means to Be ‘Liberal’ or ‘Conservative’ in China: Putting the Country’s Most Significant Political Divide in Context,” by Taisu Zhangs. (Items in parenthesis below are mine.):

“If this (the need to accumulate additional ideological resources to combat a perceived Western liberal ‘other’) is true, then one of the most important takeaways from Pan and Xu’s paper is that the educated Chinese population continues to formulate its ideological positions either against or in support of some perception of the West. In some fundamental way, we (Chinese) continue to define ourselves in relation to the Western other. This is, in fact, how the Chinese intellectual and political world has operated since the late Qing, when the influx of Western technology, institutions, and thought forced Confucian elites to fundamentally reorient their ideological commitments. Perhaps more than any flawed conception of Confucian culture, this is what we should be grappling with when considering the influence of historical tradition on contemporary Chinese society.”