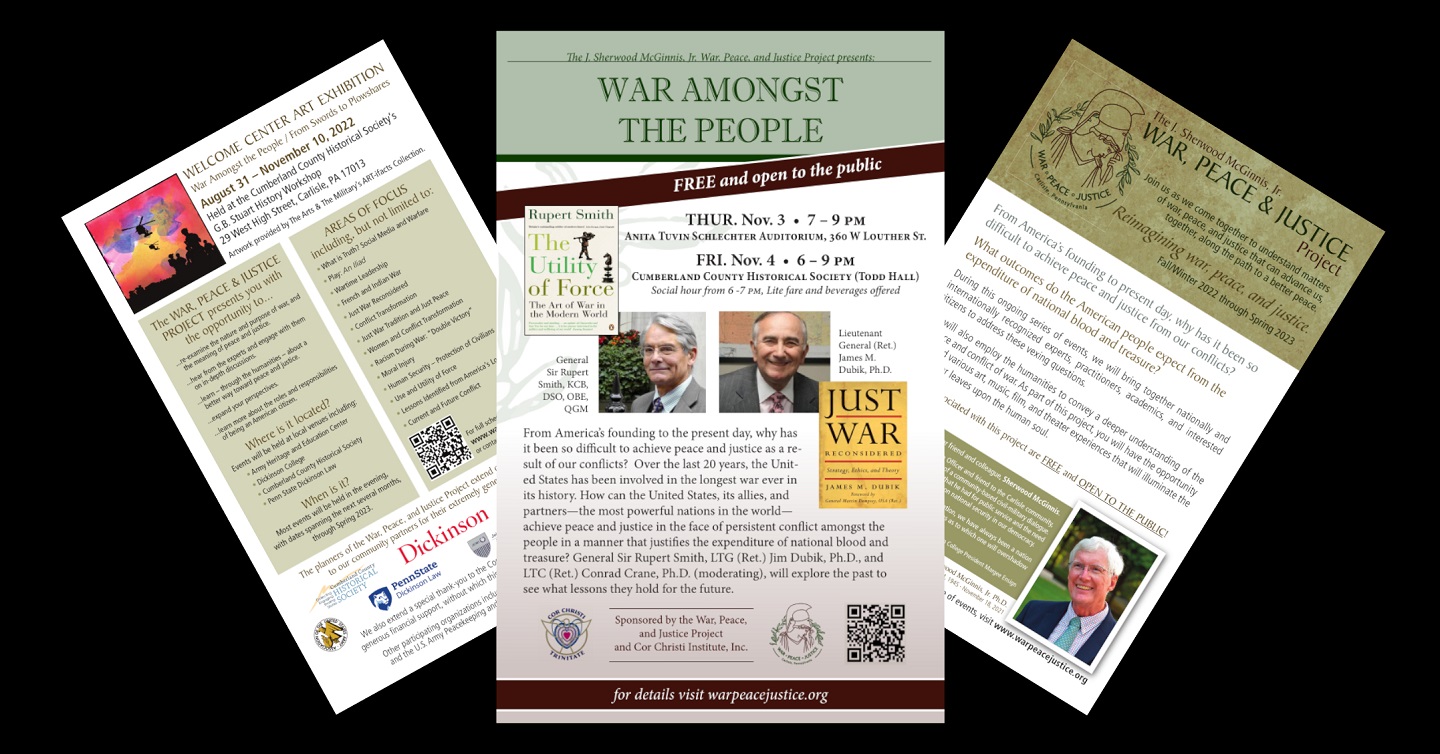

Every year the amount of sheer talent, knowledge and experience that comes through the little town of Carlisle, PA is astounding. There is the student body at the Army War College and the nation’s leaders that present as part of the curriculum, the number of academic powerhouses associated with Dickinson College and Penn State Dickinson Law, and the speaker program at the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center. Added to that list is the J. Sherwood McGinnis, Jr. War, Peace and Justice Project (WPJP) which began its Fall/Winter presentation schedule in October this year. A BETTER PEACE was fortunate enough to sit down with two of the program’s main presenters, General Sir Rupert Smith and LTG (Ret.) Jim Dubik, Ph.D., to discuss the project’s main theme: “Why has it been so difficult to achieve peace and justice as a result of our conflicts?” The two soldier-authors shared their thoughts and experiences with podcast editor Ron Granieri in a captivating conversation.

Be sure to check out the project’s website at https://www.warpeacejustice.org/ for future events. And visit the Cumberland County Historical Society where the project was hosted the next time you’re in Carlisle.

I think the last really good national conversation we had about war and its implications, and how to fight and wage it was post World War II.

Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | Podchaser | Podcast Index | TuneIn | Deezer | Youtube Music | RSS | Subscribe to A Better Peace: The War Room Podcast

James Dubik is a retired army lieutenant general, he is former Commanding General, 25th Infantry Division, and former Commanding General, First U.S. Corps. Currently, General Dubik is a Senior Fellow at the Institute for the Study of War and Institute for Land Warfare, President and CEO of Dubik Associates and a 2021-2022 George Washington Research Fellow at the Fred W. Smith National Library. General Dubik is the author of Just War Reconsidered: Strategy, Ethics, and Theory (2018) and the current Chair of the J. Sherwood McGinnis, Jr. War, Peace and Justice Project

General Sir Rupert Anthony Smith, KCB, DSO, OBE, QGM is a retired British Army officer and author of The Utility of Force: The Art of War in the Modern World (2nd edition, 2019). General Smith is also a senior advisor to the J. Sherwood McGinnis, Jr. War, Peace and Justice Project . General Smith retired from the British Army on 20 January 2002. His last appointment was NATO Deputy Supreme Commander Allied Powers Europe, 1998-2001, covering the alliance’s Balkan operations, including operations in Kosovo, and is a Visiting Professor at Reading University, a Fellow of Kings College London, and a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.

Ron Granieri is Professor of History and the Chair of the Department of National Security and Strategy at the U.S. Army War College and the Editor of A BETTER PEACE.

The views expressed in this presentation are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Review of the FY 2022 Department of Defense Budget Request before the U.S. Senate Appropriations Committee

Photo Credit: MC1 Carlos M. Vazquez II, U.S. Navy

I like the work you share

When one is engaged in “transformative” and/or “development” efforts — for example as described by Samuel P. Huntington, our own Joint Publication 3-22 Foreign Internal Defense and Senator Benjamin M. Tillman below — then (a) such things as “peace and justice,” these can be (and indeed must be?) (b) knowingly — and indeed on purpose — ignored?:

Huntington:

“The apparent relationship between poverty and backwardness, on the one hand, and instability and violence, on the other, is a spurious one. It is not the absence of modernity but the efforts to achieve it which produce political disorder. If poor countries appear to be unstable, it is not because they are poor, but because they are trying to become rich. A purely traditional society would be ignorant, poor, and stable.”

(See Page 41 of Samuel P. Huntington’s famous “Political Order in Changing Societies.”)

JP 3-22:

“a. An IDAD (Internal Defense and Development Program) integrates security force and civilian actions into a coherent, comprehensive effort. Security force actions provide a level of internal security that permits and supports growth through balanced development. This development requires change to meet the needs of vulnerable groups of people. This change may, in turn, promote unrest in the society. The strategy, therefore, includes measures to maintain conditions under which orderly development can take place.”

(See our own Joint Publication 3-22, Foreign Internal Defense; therein, see Section II, Internal Defense and Development Program, and there, Chapter 2, Construct.)

Senator Tillman (re: the Philippines cir. 1899):

“Those peoples are not suited to our institutions. They are not ready for liberty as we understand it. They do not want it. Why are we bent on forcing upon them a civilization not suited to them and which only means in their view degradation and a loss of self-respect, which is worse than the loss of life itself?… The commercial instinct which seeks to furnish a market and places for growth of commerce or the investment of capital for the money making of the few is pressing this country madly to the final and ultimate annexation of these people regardless of their own wishes.”

(http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/gilded/empire/text7/tillman.pdf)

Thus:

a. The “trying to become rich” efforts of individuals and/or states and societies; these are:

b. Generally exempt from the laws of war?

Sir Adam Roberts, in his essay “Transformative Military Occupations: Applying the Laws of War and Human Rights,” seems to address (a) certain of the “peace and justice” matters discussed in this podcast and (b) certain of the matters that I try to address in my comment above. In this regard, here is an excerpt from the first two paragraphs of Roberts’ such essay:

“Within the existing framework of international law, is it legitimate for an occupying power, in the name of creating the conditions for a more democratic and peaceful state, to introduce fundamental changes in the constitutional, social, economic, and legal order within an occupied territory? …

These questions have arisen in various conflicts and occupations since 1945 — including the tragic situation in Iraq since the United States–led invasion of March–April 2003. They have arisen because of the cautious, even restrictive assumption in the laws of war (also called international humanitarian law or, traditionally, jus in bello) that occupying powers should respect the existing laws and economic arrangements within the occupied territory, and should therefore, by implication, make as few changes as possible.”

The first two paragraphs of Section IV – “Conclusion: The Relevance of the Laws of War and Human Rights” — from the above-referenced Sir Adam Roberts essay — this also is very interesting:

“The idea of achieving the transformation of a society through a military intervention is far from new. It was a key element in much European colonialism and in France’s wars after the Revolution of 1798. The United States, with its long-held vision of itself as a reformer of a corrupt international system, has been particularly attracted by the idea, but has devoted surprisingly little attention to either to the checkered history of transformative interventions or to the prescriptive question of how they should be conducted.

The need for foreign military presences with transformative political purposes is not going to disappear. The U.S. government belatedly recognized this circumstance (and implicitly recognized that mistakes had been made in Iraq) in 2004-2005, when it established the Office of the Coordinator for Reconstruction and Stabilization. Based in the State Department, the office was charged with leading U.S. government civilian capacity ‘to prevent or prepare for post-conflict situations, and to help stabilize and reconstruct societies in transition from conflict or civil strife, so they can reach a sustainable path toward peace, democracy and a market economy.’ ”

Herein to note that — with the discussion of such things as a forced move in the occupied country to a “market economy” — as noted in the last sentence of the “conclusion” above:

a. Again the “trying to become rich” motive of people inside and/or outside of an occupied country,

b. This again seems to allow that these such “transformative” entities (for example the U.S./the West) to escape/to flout/to be exempt from the more conservative/the more traditional “make as few changes as possible” demands of international law?

(Anyone see any parallels to our problems here in the U.S./the West today; wherein, national security and/or “trying to get rich” entities are demanding market-based “change” — for example, such as “diversity, equity and inclusion” — and conservative groups, quite convincingly, are saying that [a] you risk undermining the current peace; this, [b] if you continue to pursue this such injustice to them and their traditional values?)

A look at an aspect of General Sir Rupert Smith’s “Utility of Force: The Art of War in the Modern World;” this, also, may help us consider some of the law of war questions being discussed here. Here are some key observations from GEN Smith’s such work:

“The ends for which we fight are changing from the hard objectives that decide a political outcome to those of establishing conditions in which the outcome may be decided.” And: “Our conflicts tend to be timeless, even unending.”

Compare (a) these such observations by GEN Smith to (b) this excerpt from the quote to our own Joint Publication 3-22, Foreign Internal Defense (that I provide in my initial comment above):

“This development requires change to meet the needs of vulnerable groups of people. This change may, in turn, promote unrest in the society. The strategy, therefore, includes measures to maintain conditions under which orderly development can take place.”

Herein, it would seem that (a) GEN Smith’s “establishing conditions in which the outcome may be decided” and (b) JP 3-22’s “maintain conditions under which orderly development can take place” these (c) “rhyme.”

If one takes the time now to look at an iron-clad requirement of capitalism, to wit: (a) the never-ending “creative destruction” requirement which (b) never-endingly threatens traditional social values, beliefs and institutions:

“Capitalism, he observed, creates wealth through advancing continuously to every higher levels of productivity and technological sophistication; this process requires that the ‘old’ be destroyed before the ‘new’ can take over. … This process of ‘creative destruction,’ to use Schumpeter’s term, produces many winners but also many losers, at least in the short term, and poses a serious threat to traditional social values, beliefs, and institutions.”

(From the book “The Challenge of the Global Capitalism: The World Economy in the 21st Century,” by Robert Gilpin, see the first page of the Introduction chapter.)

Then one came easily come to understand what may be behind both (a) GEN Smith “establishing conditions” observations and (b) JP 3-22’s “maintain conditions” (under which orderly development/change can take place) requirements.

Conclusion:

At the heart of LTG (ret.) Dubik’s and GEN (ret.) Smith’s thoughts (if I read them right) is the idea that (a) the reason for war; this (b) cannot be separated from the conduct of war and that, accordingly (c) civilian and military leadership must discuss things — and operate from — THAT exact such perspective.

Herein, I try to take this one step further, and try to address what — specifically — is the reason for “endless war,” both here at home and there abroad, to wit: (a) the never-ending threat to such things as traditional social values, beliefs and institutions as is (b) never-endingly posed by the “achieve revolutionary/innovative change” requirements of capitalism, markets and trade.

(From THAT such perspective to understand [a] the conflicts that we are having with “no change”/”reverse realized but unwanted change” elements here in the U.S./the West today, [b] the conflicts that we are having with “no change”/”reverse realized but unwanted change” elements in the Islamic World and [c] the conflicts that we are having with the “no change”/”reverse realized but unwanted change” great powers — ALL OF WHOM are using such things as traditional social values, beliefs and institutions against us today?)

Re: my thoughts immediately above, would Clausewitz tell us that this can — and indeed should be — greatly simplified; this, by having U.S./Western senior soldiers and statespersons address:

a. Not so much the “reason” for war

b. But, rather, the “kind” of war that we are embarked upon, to wit:

1. An unending revolutionary war which is

2. Based on the never-ending “revolutionary change” requirements of such things as capitalism, markets and trade?

Given the reference to Lindell Hart in our podcast above, let us consider (a) the never-ending “reason for war” that I suggest above (to wit: keeping up with the never-ending political, economic, social and/or value “change” requirements of such things as capitalism, markets and trade); this, from what looks to be (b) the/an “indirect approach” to achieving such a “better peace.” In doing this, let us consider (c) my never-ending “revolutionary war” suggestions above also.

In order to do all of this, let us look at the following excerpt from the Small War Journal article “Learning From Today’s Crisis of Counterinsurgency,” an interview of Dr. David H. Ucko and Dr. Robert Egnell by Octavian Manea:

“Robert Egnell: Analysts like to talk about ‘indirect approaches’ or ‘limited interventions’, but the question is ‘approaches to what?’ What are we trying to achieve? What is our understanding of the end-state? In a recent article published in Joint Forces Quarterly, I sought to challenge the contemporary understanding of counterinsurgency by arguing that the term itself may lead us to faulty assumptions about nature of the problem, what it is we are trying to do, and how best to achieve it. When we label something a counterinsurgency campaign, it introduces certain assumptions from the past and from the contemporary era about the nature of the conflict. One problem is that counterinsurgency is by its nature conservative, or status-quo oriented – it is about preserving existing political systems, law and order. And that is not what we have been doing in Iraq and Afghanistan. Instead, we have been the revolutionary actors, the ones instigating revolutionary societal changes. Can we still call it counterinsurgency, when we are pushing for so much change?

“Dhofar, El Savador and the Philippines are all campaigns driven by fundamentally conservative concerns. When we are looking to Syria right now, it is not just about maintaining order or even the regime, but about larger political change. In Afghanistan and Iraq too, we represented revolutionary change. So, perhaps we should read Mao and Che Guevara instead of Thompson in order to find the appropriate lessons of how to achieve large-scale societal change through limited means? That is what we are after, in the end. And in this coming era, where we are pivoting away from large-scale interventions and state-building projects, but not from our fairly grand political ambitions, it may be worth exploring how insurgents do more with little; how they approach irregular warfare, and reach their objectives indirectly.”

Question: Would I be correct in suggesting that Dr. Egnell above, “covers all the bases” here, to wit:

a. The never-ending “reason for war”/”better peace”/”political objective”/”strategic end” requirement? (To wit: to “achieve large-scale societal change” — from my perspective, so as to meet the never-ending “revolutionary change” requirements of such things as capitalism, markets and trade — addresses why we would historically, and again today, find resistance to same both here at home and there abroad),

b. The “indirect approach” requirement? (To wit: the manner in which such a war should be conducted; this, given its such — both here at home and there abroad — never-ending “achieve large-scale societal change” requirement.) And

c. The fact that this is, thus, a “revolutionary”-type war? (Most important, thus, “not to mistake it for something that is alien to its nature?”)

Re: a Lindell-Hart approach, considering my comments above, let us consider that the political objective is to transform the states and societies of the world — to include our own such states and societies here in the U.S./the West — this, so that same might be made to better interact with, better provide for and better benefit from such things as capitalism, markets and trade. A “better peace,” thereby, to be achieved.

This requires that such things as certain traditional values, beliefs and institutions (re: for example, religion, race, sex, etc.) become much less important to people — both within our own states and societies — and in states and societies elsewhere throughout the world.

Question: What is an “indirect approach” to achieving this such political objective; that is, the approach that (a) avoids a direct attack (and the severe losses on both sides associated with same) against these such obstructing traditional values, beliefs and institutions — and against those that have already, and/or can in the future, achieve status, power, influence and control via same — and, rather, (b) works to disrupt (in capitalism’s favor) this such enemy’s equilibrium/their “influence” “state of balance” (with capitalism, markets and trade)?

Answer: Would such things as “income redistribution” work here? (Attacks the enemy’s “weak point” and, thus, finds a/the “path of least resistance?”)