Singer, songwriter, musician, podcaster and politician John Roderick is back in the studio with podcast Editor Ron Granieri for part two of their conversation. The discussion started in part one focusing on John’s experiences during the National Security Seminar at the U.S. Army War College. But talk eventually moved to John and Ron’s thoughts about podcasting. The host of two very well subscribed shows, John points to the power of conversation in our lives. Often the dialogue that leads to open minded examination of new ideas, podcasts can be the mode of communication that reaches the masses, tests ideas, promulgates concepts or sometimes just entertains and passes the time. For some it can be their legacy, for others their pulpit and for many their therapy, regardless of their purpose, the reports of podcasting’s death are greatly exaggerated.

Well now wait a minute, we’re now treading on dangerous ground and treading on dangerous ground that’s where all the progress is. You don’t make progress by just walking around in circles inside the temple you have to get out. You have to move.

Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Android | Email | RSS

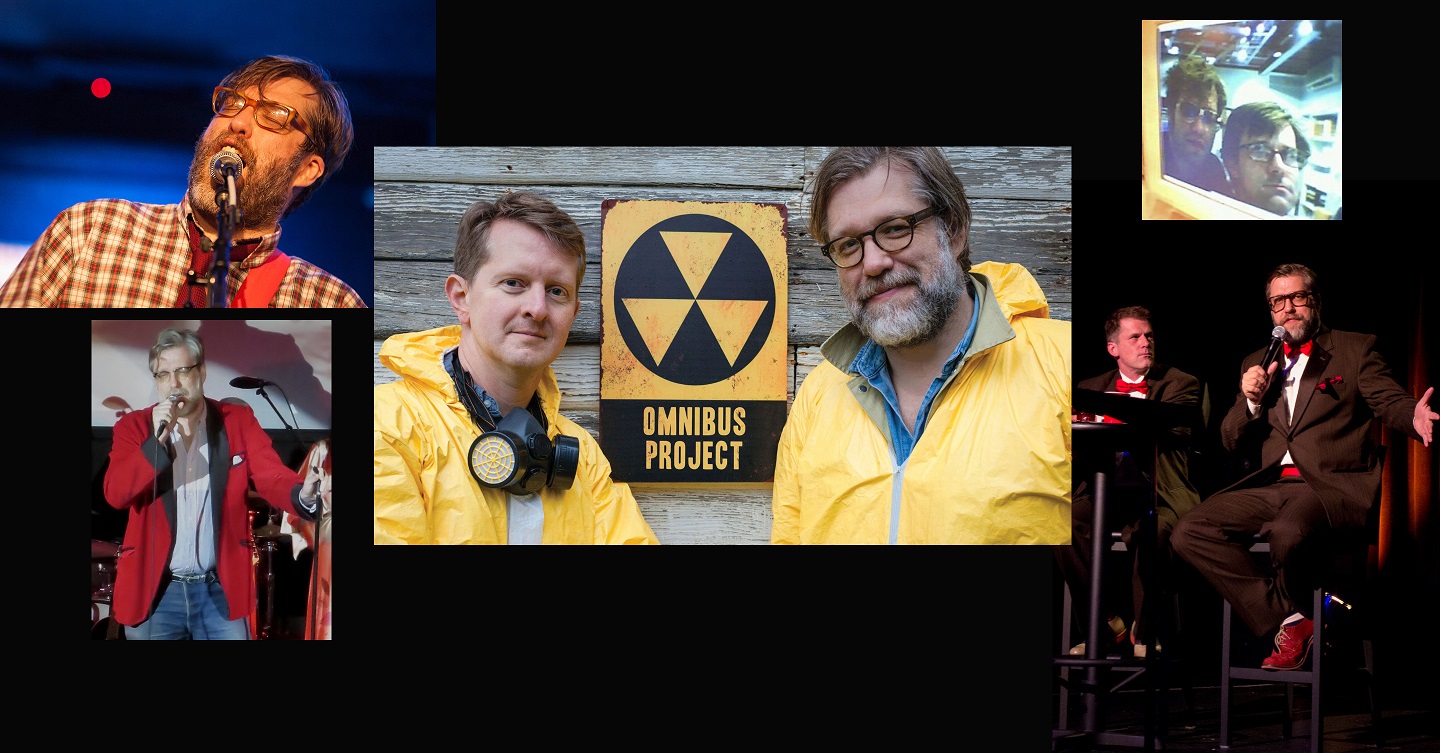

John Roderick cohosts the podcasts The Omnibus Project with Jeopardy host Ken Jennings, and Roderick on the Line with pundit Merlin Mann. He’s also the frontman of indie band The Long Winters. He lives in Seattle.

Ron Granieri is an Associate Professor of History at the U.S. Army War College and the Editor of A BETTER PEACE.

Photo Description: The many faces of John Roderick (Top Left) performing at the City Winery in New York City during his One Christmas at a Time Tour; (Top Right) podcast art for Roderick on the Line; (Bottom Right) Merlin Mann and John Roderick — Roderick on the Line, 2012; (Bottom Left) John Roderick Live at The Chapel, San Francisco CA – Jan 17, 2020; (Center) podcast art for The Omnibus Project

Photo Credit: (Top Left) Terry.r.robinson via Wikimedia Commons; (Top Right) @RoderickOn; (Bottom Right) David Lee via flickr; (Bottom Left) michaelz1 via flickr; (Center) Susan Roderick

John Roderick: “I think we are living in a time of orthodoxy.”

In that regard, let me suggest two orthodoxies:

a. The orthodoxy of “change.” Which requires that such things as traditional social values, beliefs and institutions must, periodically, give way; this, so that a nation might embrace (a) innovations which (b) would allow the nation to remain competitive and (c) allow the nation to be able to defend itself now and in the future. (For the U.S./the West, the time both before — and after — the Old Cold War; these might be considered times which in which the U.S./the West embraced this such “change” orthodoxy; in both such instances, so as to adequately benefit from such things as capitalism, globalization and the global economy?)

b. The orthodoxy of “no change.” Which requires that such things as traditional social values, beliefs and institutions must become “weaponized;” this, so that a nation might defend itself against an “other” who is bent on achieving (what a particular nation considers as) negative innovation and change. (For the U.S./the West during the Old Cold War — and for such entities as China, Russia, Iran, N. Korea and the Islamists in the New/Reverse Cold War of today — these are times in which these such nations have embraced the orthodoxy of “no change?”)

The Orthodoxy of Change: a seemingly paradoxical and concise way of describing our country’s defining institution.

John Roderick: “You don’t make policy and then talk about it, you talk about it and, from that, make policy.”

In that regard, consider that — what seems to have gotten us to where we are today — this was the then-general consensus and agreement (achieved by “talking about it” back then?) which developed between most elements of the Right and the Left after the Old Cold War — and which suggested that (a) economic competition would be the defining characteristic of the new post-Cold War international order and that, accordingly, (b) the nations of the world who were most able to overcome their cultural backwardness problems (think various non-capitalism, globalization and global economy-based traditional social values, beliefs and institutions), these such “further developed” nations would prevail over other nations (who, for various reasons, would not, or simply could not, likewise improvise, adapt, overcome and “change”):

“We agree with Bobbitt that a global transition from Nation States to Market States is now well underway. The chief thesis of this Article is that the Supreme Court has embarked on a program of reshaping constitutional doctrine so as to encourage and facilitate the emergence of a fully developed Market States in this polity, with a view to positioning the United States to be successful in meeting the competitive challenges of a new, post-Cold War international order. In taking this course, the Court has increasingly aligned itself with the prescriptive view of American business and political elites, for whom globalization is understood ‘not merely [as] a diagnostic tool but also [as] an action program.’ ”

(See the only full paragraph of Page 643 of the 2005 Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law paper entitled “Moral Communities or a Market State: The Supreme Court’s Vision of the Police Power in the Age of Globalization,” by Antonio F. Perez and Robert J. Delahunty.)

Bottom Line Thought — Based on the Above:

Thus, the problem with our current situation, this would not seem to relate to an error of failing to adequately talk about policy before adopting same.

Rather, the problem would seem to be with failing to establish a strategy to address the classic problems associated with these such “development”/”change” initiatives, for example, as described (re: a foreign/partner government in this case) in our Joint Publication 3-22 “Foreign Internal Defense” below. (Therein, see Chapter II, “Internal Defense and Development Program,” and Paragraph 2, “Construct”):

“a. An IDAD (Internal Defense and Development) program integrates security force and civilian actions into a coherent, comprehensive effort. Security force actions provide a level of internal security that permits and supports growth through balanced development. This development requires change to meet the needs of vulnerable groups of people. This change may, in turn, promote unrest in the society. The strategy, therefore, includes measures to maintain conditions under which orderly development can take place.”

Bottom Line Question — Based on the Above:

As the U.S./the West moved to further “develop” — so as to prevail in the “economic competition” environment of the post-Cold War — U.S./the West DID NOT, it would seem, and as per JP 3-22 above, (a) have a strategy in place (which, indeed, might require the deployment of military, police and intelligence assets?) — as strategy, thus, which (b) “included measures to maintain conditions under which orderly development might take place.”

(Thus, the problem here would not seem to be about adequate “talking,” nor about the failure to achieve a consensus re: “policy,” but, rather, the failure to develop an adequate “strategy” — by which — the agreed-upon policy might be adequately implemented and achieved?)

The following may — or may not — provide “food” for innumerable “podcasts.” Here goes:

Given that “change” would seem to be a constant and, indeed, a never-ending requirement; this, for nations who are properly concerned with such things as national security;

Given this such requirement, periods of “resistance to change” — such as we have seen both here at home and there abroad of late — these, also it would seem, must be a perennial features of history. Yes?

In this regard, and re: the U.S./the West in this case, here might be some examples of these such “resistance to change” instances:

“Jacksonians drew their support from Northern laborers and yeoman farmers in the South and in the West. These groups, which Jackson dubbed the ‘bone and sinew of America,’ worried that the market economy would force them into the dependent class. The Jacksonians told the farmers and the laborers that they would do everything in their power to prevent this from taking place. In essence, the men and their rank and file voting allies, along with Jackson, fought a rear-guard action against encroaching industrialization and market economy. Although they won the pivotal battles, they lost the war, because their notion of a pre-capitalist agrarian society succumbed to the industrial economy after the Civil War.”

(See the ‘Encyclopedia of U.S. Political History’ by Andrew Robertson, et al., and the section therein entitled ‘Jacksonian Democracy,’ Page 194.)”

“In this new world disorder, the power of identity politics can no longer be denied. Western elites believed that in the twenty-first century, cosmopolitanism and globalism would triumph over atavism and tribal loyalties. They failed to understand the deep roots of identity politics in the human psyche and the necessity for those roots to find political expression in both foreign and domestic policy arenas. And they failed to understand that the very forces of economic and social development that cosmopolitanism and globalization fostered would generate turbulence and eventually resistance, as ‘Gemeinschaft’ (community) fought back against the onrushing ‘Gesellschaft’ (market society), in the classic terms sociologists favored a century ago.”

(See the Mar-Apr 2017 edition of “Foreign Affairs” and, therein, the article by Walter Russell Mead entitled “The Jacksonian Revolt: American Populism and the Liberal Order.”)

Bottom Line Question — Based on the Above:

Do we agree with Walter Russell Mead above, re: his “Western elites failed to understand” thought?

Or, in stark contrast to this such “they failed to understand” thought, might we say that these such elites — tasked with maintaining “national security” in a rapidly changing world — had no choice but to proceed toward “change” anyway (much as President Lincoln did?); this, in spite their understanding that “change” — as it nearly always does — generates “resistance to change?”

(Again: Food for innumerable “podcasts?”)

Given the two “market society” versus “community” examples — that I provide at my Sep 1, 2022 at 1:21 pm comment immediately above — I probably should have put a much finer “market” point on my “perpetual nature of change versus resistance to change” thoughts there.

From that such “the market demanded these such changes” (and, in the name of nation security, U.S./Western leadership agrees) point of view, thus to see:

a. The historic “resistance to MARKET-demanded change” example provided at my first quoted item above (in that case, as related to Andrew Jackson’s time) and

b. The historic “resistance to MARKET-demanded change” example provided at my second quoted item above (wherein, at the very end of this such quoted item, Walter Russell Mead points to a period similar to today which occurs “a century ago.”)

Thus, the perennial nature of the events that we are witnessing today, these SHOULD NOT be considered along some random, generic and generally disconnected “change versus resistance to change” lines.

Rather, these such events must be viewed within the — very specific — “MARKET-based changes cause these such disruptions” lines addressed, for example, by Jerry Z. Muller below. (Herein, note how Muller states that these such disruptions have occurred — and recurred — since at least the dawn of modern capitalism in the 18th Century):

“All in all, the 1980s and 1990s (the 2000s and the 2010s also; Muller’s book was written in 2002) were a Hayekian moment, when his once untimely liberalism came to be seen as timely. The intensification of market competition, internally and within each nation, created a more innovative and dynamic brand of capitalism. That in turn gave rise to a new chorus of laments that, as we have seen, have recurred since the eighteenth century: Community was breaking down; traditional ways of life were being destroyed; identities were thrown into question; solidarity was being undermined; egoism unleashed; wealth made conspicuous amid new inequality; philistinism was triumphant.”

(From the book “The Mind and the Market: Capitalism in Western Thought” by Jerry Z. Muller; therein, see the chapter on Friedrich Hayek.)

Bottom Line Question — Based on the Above:

With the U.S./the West having — even before the end of the Old Cold War — this much historical “market society” versus “community” knowledge and experience before it,

Why is it that the U.S./the West — after the Old Cold War — would generally ignore same?

Let’s take a different tack now — and look at the “market society versus community” national security matters that I addressed in my comments above — this, through the “irregular warfare” lens provided by the following two quoted items:

“Irregular warfare is a struggle among state and non-state actors for legitimacy and influence over relevant populations.”

(See Page 2 of the “Summary of the Irregular Warfare Annex to the National Defense Strategy;” therein, see the first sentence of the major section there entitled “Irregular Warfare: An Enduring Mission and Core Competency.”)

“Our adversaries seek to undercut our global influence, degrade our relationships with key allies and partners, and shape the global environment to their advantage without provoking a U.S. conventional response.”

(In this case, see Page 4 of the “Summary of the Irregular Warfare Annex to the National Defense Strategy;” therein, see the first sentence of the major section there entitled “We Remain Underprepared for Irregular War.”)

Bottom Line Question — Based on the Above:

Via their moves to embrace “community” rather than “market society,” can we say that such nations as Russia and China, today, have made great strides; this, in winning today’s irregular wars?

“Liberal democratic societies have, in the past few decades, undergone a series of revolutionary changes in their social and political life, which are not to the taste of all their citizens. For many of those, who might be called social conservatives, Russia has become a more agreeable society, at least in principle, than those they live in. Communist Westerners used to speak of the Soviet Union as the pioneer society of a brighter future for all. Now, the rightwing nationalists of Europe and North America admire Russia and its leader for cleaving to the past.”

(See “The American Interest” article “The Reality of Russian Soft Power” by John Lloyd and Daria Litinova.)

“This may, in fact, be the missing explanatory element. Ideologies regularly define themselves against a perceived ‘other,’ and in this case there was quite plausibly a common and powerful ‘other’ (to wit: Western liberalism) that both (Chinese) cultural conservatism and (Chinese) political leftism defined themselves against. This also explains why leftists have, since the 1990s, become considerably more tolerant, even accepting, of cultural conservatism than they were for virtually the entire 20th century. The need to accumulate additional ideological resources to combat a perceived Western liberal ‘other’ is a powerful one, and it seems perfectly possible that this could have overridden whatever historical antagonism, or even substantive disagreement, existed between the two positions.” (Items in parenthesis above are mine.)

(See the April 24, 2015 Foreign Policy article “What it Means to Be ‘Liberal’ or ‘Conservative’ in China:

Putting the Country’s Most Significant Political Divide in Context” by Taisu Zhang.)

Do you have a way to subscribe to the feed that will work in Overcast?

The RSS feed for the podcast returns a 403 “Forbidden” when I request it.

I am trying the URL: https://warroom.armywarcollege.edu/category/podcasts/feed/