EDITOR’S NOTE: The current temporary theme we are using only credits a single author. This article was written by Sebastian Bae and Paul Kearney.

The majority of educational wargaming is confined to the classroom, far removed from frontline units.

Educational wargaming is increasingly prevalent in the pedagogical toolkit but remains concentrated at the higher levels of Professional Military Education (PME). Advanced PME institutions like the U.S. Army War College and the Marine Corps War College are admirably expanding game-based learning in their curricula. In contrast, educational wargaming remains generally underdeveloped and underutilized in the operational force. The majority of educational wargaming is confined to the classroom, far removed from frontline units. At the tactical edge, wargaming is generally limited to the military planning process and course of action analysis. The rare employment of educational wargaming within tactical units is episodic and limited in scope. Thus, to systemically reap the dividends of educational wargaming, the Joint Force should aim to reestablish the tradition of educational wargaming within tactical units. Success depends on senior leadership support in the form of institutional funding and enduring partnerships with wargaming organizations.

The use of wargames to teach both tactics and strategic thinking lies at the heart of professional wargaming. Wargames provide a dynamic environment to explore and examine a variety of challenges and concepts along the strategic, operational and tactical levels. As an educational tool, wargaming fosters critical thinking and innovation, but most of all, it helps prepare tactical leaders for future challenges.

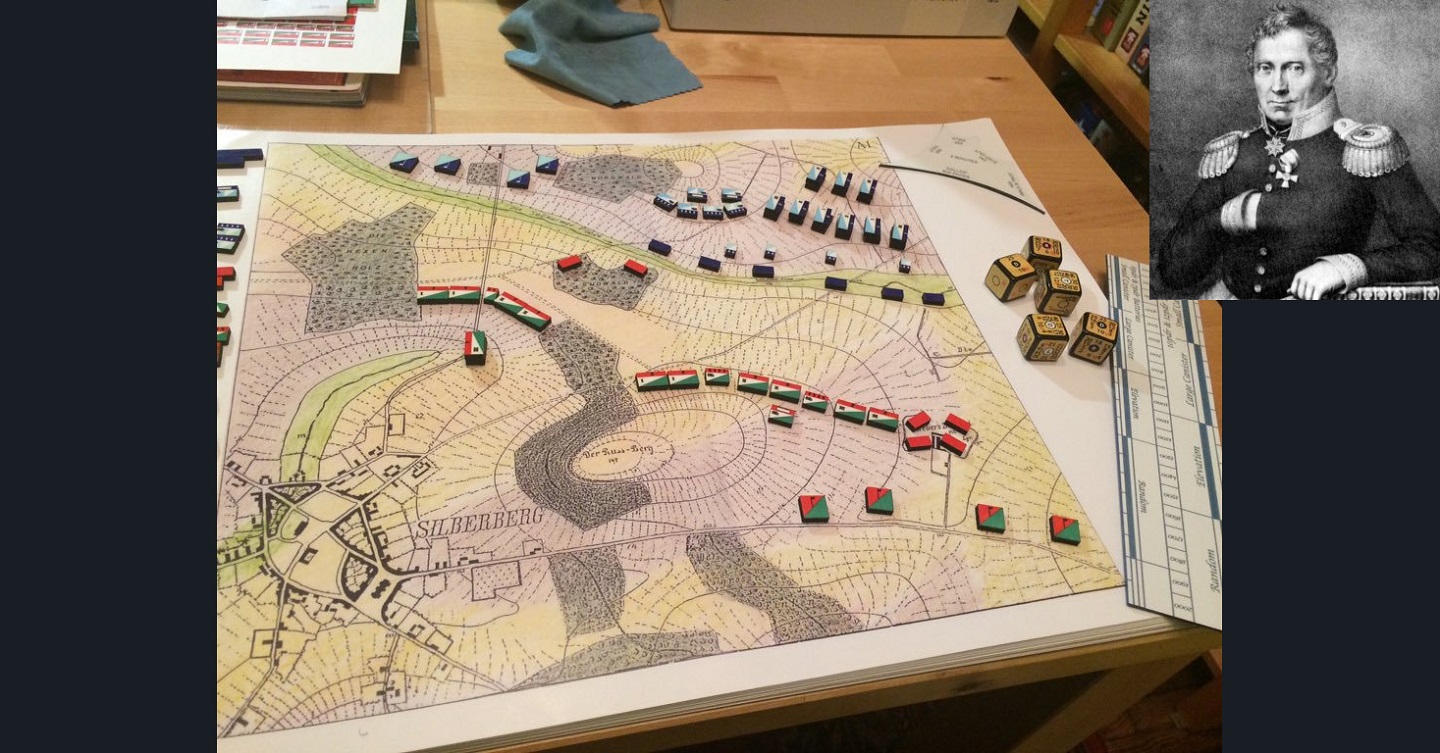

From its inception in the early 19th century, the Prussian Kriegsspiel, the progenitor of modern wargaming, was designed to educate and train Prussian officers for future wars. When observing a Kriegsspiel demonstration in 1824, General Karl von Muffling, Chief of the Prussian General Staff, famously exclaimed, “This is not a game, this is a war exercise! I must recommend it to the whole army!” Subsequently, a copy of the wargame was supplied to each regiment in the Prussian army, which spurred the formation of Kriegsspiel–centric clubs. The enduring popularity of Kriegsspiel centers on its ability to provide players a means to garner experience, explore difficult challenges and hone decision-making skills under stress.

In 1880 American Army officer Charles Totten published “Strategos,” a series of tactical wargames with varying scenarios and levels of complexity. Most notably, “Strategos” stressed accessibility across echelons and was later disseminated to company-sized units. From 1977 to 1997, the Dunn Kempf wargame was widely used as a teaching tool and explored potential combined arms warfare in Europe against a Soviet-led Warsaw Pact. With its memorable 1/285 scale miniatures and emphasis on small-unit tactics, Dunn Kempf enabled soldiers to familiarize themselves with enemy capabilities, execute varying battle plans and learn through competition and iteration. Similarly, Harpoon, a tactical miniatures wargame series, was originally used as a training tool for naval officers during the Cold War. Emphasizing the interplay of sensors and weapon systems, Harpoon enabled players to realistically explore the dynamics of modern naval warfare. Unfortunately, over time, the ability of uniformed servicemembers to design or conduct their own wargames has largely atrophied.

Although the Soviet Union is gone, new competitors and challenges are on the operational horizon, such as a growing Chinese navy and the rising threat of Russia’s long-range missile capabilities. In the “Commandant’s Planning Guidance,” General David H. Berger clearly stated, “Wargaming historically was invented to fill this gap, and we need to make far more aggressive use of it at all levels of training and education to give leaders the necessary ‘reps and sets’ in realistic combat decision-making.” As concepts like multi-domain operations evolve and new capabilities are fielded, the necessity for educational wargaming within the operating forces becomes increasingly poignant. By conducting wargames, tactical leaders from Sergeants to Majors not only familiarize themselves with capabilities but also face a thinking and adaptive adversary. Admittedly, the 2015 memo by DEPSECDEF Bob Work and the 2020 guidance on PME by the Joint Chiefs of Staff have recently rekindled interest in game-based learning. However, significant challenges remain if educational wargaming is to grow and persist at the tactical edge of the Joint Force.

Whether attempting to establish or grow wargaming initiatives, resistant or reluctant leadership is typically the first barrier to overcome. Some commanders view wargaming as a childish endeavor or an oversimplification of the complexities of warfare, unworthy of the requisite time and resources. This often results in wargaming initiatives at tactical units never garnering the necessary momentum and support. The reluctance of leadership to embrace wargaming is further compounded by a litany of operational and administrative requirements resident in tactical units. From the brigade to the squad level, tactical units must juggle their respective missions, unit readiness, rigid training schedules and other demands on their finite time. Predictably, wargaming initiatives can struggle to gain traction amidst the cacophony of competing priorities such as weapons qualifications, mandatory annual training briefs and scheduled field exercises.

Even when units manage to navigate these initial barriers, the overreliance on individual-led initiatives and the absence of wargaming expertise can become critical limitations. Unlike PME institutions which often benefit from dedicated wargaming staff, educational wargaming at the tactical level routinely relies on intrinsically motivated individuals – akin to the Prussian Kriegsspiel clubs. Servicemembers with a background in hobby gaming typically cultivate wargaming within their respective units, as reflected in the use of Advanced Squad Leader by the 1st Battalion Royal Irish in the British Army. However, sustaining and growing these nascent wargaming initiatives requires niche expertise and experience which is often lacking in the operating forces.

If educational wargaming is to be a constant feature in how the services educate and train future warfighters, systemic reform is required.

A grassroots wargaming construct that lacks institutional backing is vulnerable to the constant circulation of personnel in the military establishment and can generate a cycle of exponential growth of wargaming within units followed by a precipitous decline as key individuals depart for new assignments. If educational wargaming is to be a constant feature in how the services educate and train future warfighters, systemic reform is required. The services should strive to provide institutional support for grassroots wargaming organizations, equip units with diverse wargaming tools and provide guidance and wargaming expertise to the operating forces.

In spite of significant challenges, educational wargaming within the operating forces endures in scattered pockets of excellence. For instance, the 4th Marine Regiment, 3rd Marine Division used Memoir ’44, a commercial wargame about the Second World War, to foster critical thinking skills in junior marines. In recent years, grassroots professional development organizations, such as chapters of the Warfighting Society, have spread across military installations. Using methods ranging from wargaming to structured discussions, they aim to advance the profession of arms and develop critical decision-making skills in their members.

The concept of underground professional development with an emphasis on wargaming has expanded globally, as reflected in the U.K. Fight Club and the Australian Fight Club. However, a paradigm shift is required so that these efforts are not seen as extracurricular activities but rather as essential to the education of future leaders across the rank and file. Ideally, this brand of self-directed education and development will foster numerous laboratories of innovation and learning – reminiscent of the interwar wargaming at the U.S. Naval War College. Senior leadership support will prove essential in broadly normalizing these initiatives.

For sustained success, organizational approval from senior leadership should manifest as material support, including the establishment of specific educational wargaming funds similar to the Wargaming Incentive Fund. These funds would encourage units to acquire a range of wargaming tools and to support game-based learning within their respective commands. Equipped with funding, units could build wargaming libraries, ranging from commercial off-the-shelf games to tailored educational wargames like U.S. Marine Corps Wargaming Division’s Assassin’s Mace and the UK Defense Science and Technology Library’s Strike!. Moreover, the integration of digital tactical decision games and digital wargames, such as Command PE, Flashpoint Campaigns, Combat Mission: Shock Force 2 could become more feasible.

The services should outline official guidance on the use of educational wargaming at the tactical level and foster regular collaboration between the operating forces and wargaming organizations. For instance, the services could craft a recommended professional wargaming list, modeled on the Commandant of the Marine Corps Professional Reading List. This idea is not new. In a 1994 Marine Corps Gazette article, “Why not a Commandant’s Wargame and Simulation List?” LtCol David A. Bartlett and Major Robert F. Curtis similarly proposed a Commandant’s Wargaming List. The professional wargaming list could identify potential educational wargames for tactical units, categorized by playability, theme, warfighting function and learning objectives. Ideally, the list would mandate commanders to encourage and enable wargaming within their units. Elevating educational wargaming as a training priority helps mitigate the problems posed by resistant leadership and competing requirements. Eventually, the professional wargaming list could include standard operating procedures and lessons learned based on the experiences of participating units. This process will assist leaders in finding and employing suitable educational wargames while enabling their feedback to further improve future iterations. Admittedly, it is a precarious balance between cultivating a fertile environment for wargaming and relegating wargaming to the mandatory training list.

Lastly, the services should foster habitual collaboration between the operating force and wargaming organizations enabling the transfer of wargaming expertise. PME institutions, professional wargaming societies, think tanks and civilian universities can serve as valuable collaborators. The Brute Krulak Center for Innovation and Creativity, U.S. Air Force Research Lab and Naval Postgraduate School represent just a few potential partners. For instance, the educational wargames designed by students at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College and Georgetown University could serve as a source of tailored-made wargames for tactical units. Additionally, wargaming partners could provide wargaming certification courses, host webinars on educational wargaming, serve as subject-matter experts and facilitate large-scale wargaming events. Inter-organizational collaboration may dramatically broaden the realm of wargaming possibilities for the operating force.

Wargaming has repeatedly demonstrated the power and allure of game-based learning from the original Kriegsspiel clubs to modern-day warfighting societies. James Sterrett, Chief of the Simulation Education Division at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College once commented, “Experience is a great teacher and well-designed games can deliver experiences that are tailored to drive home learning.” Yet, as a growing consensus embraces the utility of educational wargaming, a more daunting question remains: Can the Joint Force integrate and sustain educational wargaming in the operating forces? The challenges are substantial, but they are not insurmountable. The answer depends on bold leadership, sufficient tools and eager partners, which begs the final question: Are you ready to play?

Sebastian J. Bae, a defense analyst at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation, works in wargaming, emerging technologies, the future of warfare, and strategy and doctrine for the U.S. Army and Marine Corps. He also serves as an adjunct assistant professor at the Center for Security Studies at Georgetown University, where he teaches a graduate course on designing educational wargames. Follow him @SebastianBae on Twitter. MAJ Paul M. Kearney is an active-duty Army Strategist and Wargaming Strategist at the Center for Army Analysis. He holds degrees from the United States Military Academy, King’s College London, and Georgetown University. You can follow him @GStrategerist on Twitter. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense, or the RAND Corporation.

Photo Description: A reconstruction of a Prussian military wargame (kriegsspiel), based on a ruleset developed by Inset: Georg Heinrich Rudolf Johann von Reiswitz in 1824.

Photo Credit: Matthew Kirschenbaum via Wikimedia Commons, Inset unknown

Great write-up! The Southern California Kriegsspiel Society runs Kriegsspiel games (Free Kriegsspiel, usually American Civil War scenarios), several times a year. Usually in-person, and now online. They have a Facebook page, and all are welcome.

As is often the case with the introduction of new doctrine and concepts, leaders first learn about such things while enrolled in a course of professional military education (PME). Critical to getting wargames to become a part of what tactical and operational (and to a lesser extent strategic) units think of as “good training” is to make the use of a variety of wargames as a part of all PME experiences. It is during these PME experiences that non-gamers will come to appreciate the value of games as tool for sharpening critical thinking and planning skills and will be exposed to benefits of games as an opportunity to get in the “reps and sets” the authors spoke about.

The effort needs to begin at pre-commissioning for officers and during the warrior leaders course for non-commissioned officers. Unfortunately, the use of wargames at this level seems to be spotty at best. Fortunately, there are many commercial tactical games that will fit the bill, Memoir 44 being an example cited in the article. There are also a number of good operational level wargames that would be useful for the intermediate level of MPE. At the higher end of PME, the number of useful commercial games declines rapidly. Fortunately, all of the senior service colleges seem to have a capability to develop custom strategic-level games that nest well into the curriculum. However, there is still work to be done to make wargames a routine part of PME at all of the senior service colleges. Once leaders at this upper level of PME encounter wargames routinely, they will be come to understand and appreciate the value of wargaming and will begin to expect leaders at lower levels to have wargames experiences as well.

At the higher end of PME the number of useful commercial games multiplies exponentially. ‘Memoir 44’, cited wrt the lower end, is useful for enlisted personnel. Wargames for officers are available in vast profusion, although the useful ones require military-analytic skills or at least aptitude. It is easy to build a wrap around these lab tools to enable the students to learn the MPP, MDMP, CFA and related staff methods experientially in a way they will remember for the rest of their lives.