WAR ROOM has presented our readers and listeners with a number of discussions in the past on Women in Peace and Security. In this episode our Editor-in-Chief, Jacqueline Whitt sits down in the virtual studio with Lauren Buitta, founder and CEO of Girl Security. Lauren began her career as a policy analyst in 2003, and she quickly recognized the underrepresentation of women in the national security arena. In response, she launched Girl Security – the only organization dedicated to advancing girls, women, and gender minorities in national security through supportive pathways. Their conversation includes the barriers young women encounter as well as the incredibly successful mentorship program Girl Security has developed to counter mindsets and misrepresentations.

If we can start understanding the root causes of a lack of diversity in national security that begin well before college, we can first of all, gather more data about why diversity in national security matters, but we can also develop better interventions to catalyze more diversity in national security over the next 10 to 20 years.

Podcast: Download

Lauren Buitta is founder and CEO of Girl Security, a nonprofit organization advancing girls, women, and gender minorities in national security through supportive pathways. She began her career in national security in Chicago, IL in 2003 as a policy analyst with the National Strategy Forum, a nonpartisan national security think tank, where she focused on national security law. Prior to launching Girl Security, Lauren founded a consulting firm, which provided support to clients on local policy issues, including exclusionary land use policies and racial segregation in Chicago.

Jacqueline E. Whitt is an Associate Professor of Strategy at the U.S. Army War College and the Editor-in-Chief of WAR ROOM.

The views expressed in this presentation are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

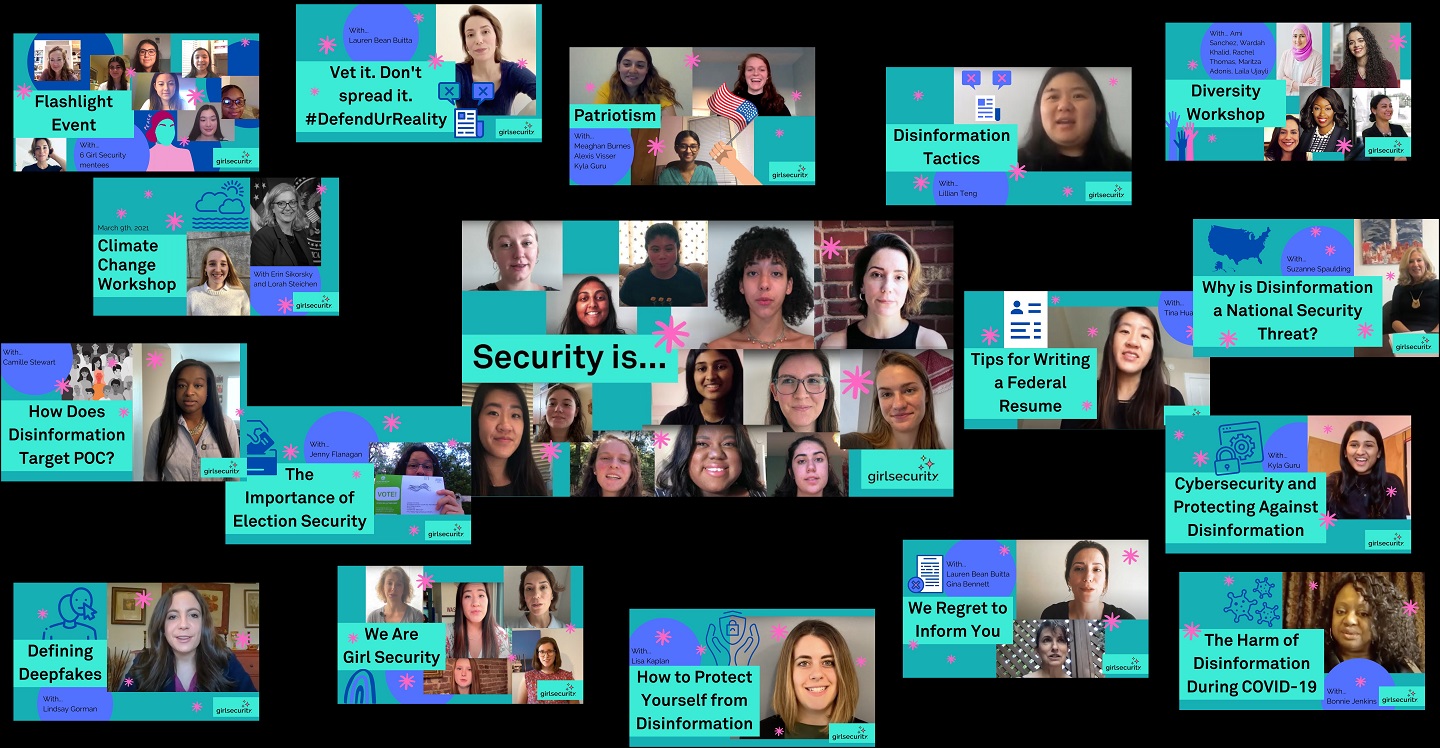

Photo Description: One of the many tools used by Girl Security to reach out to young women is video presentations of prominent role models as well as peers in the national security realm speaking about their experiences and participating in panels.

Photo Credit: All photos are captured from videos presented on Girl Security’s YouTube channel.

Such things as “diversity,” writ-large, these things seems to need to be considered, today, from the following perspective:

a. The U.S./the West, post-the Cold War, seeking to achieve — both at home and abroad — such political, economic, social and/or value changes as are necessary; this, so as to allow that the states and societies of the world (to include our own) might be made to better interact with, better provide for and better benefit from such things as capitalism, globalization and the global economy. (It is from this such perspective, I suggest, that having more women, blacks, gays, etc., etc., etc., in business, government and national security, etc. is considered to be not only desirable but indeed essential.) And from the perspective of:

b. Our status quo-loving opponents (those both here at home and there abroad), thus threatened by the U.S./the West’s such global “change” agenda, seeking to (a) retain what power, influence and control they currently have (and/or to regain power, etc., that they recently lost); this, by (b) standing hard against (and/or reversing) such political, economic, social and/or value changes as the U.S./the West (see my item “a” above) recently achieved — and/or seeks to achieve in the near future.

Fiona Hill, in her article “The Kremlin’s Strange Victory: How Putin Exploits American Dysfunction and Fuels American Decline” in the current (Nov-Dec 2021) issue of “Foreign Affairs,” seems to describe the dynamic that I note at my item “b” above in terms of a “conservative” U.S. — and a “conservative” Russia today — thus similarly threatened — having thus a “Special Relationship:”

“The Mueller report also sketched the contours of a different, arguably more pernicious kind of ‘Russian connection.’ In some crucial ways, Russia and the United States were not so different–and Putin, for one, knew it. In the very early years of the post-Cold War era, many analysts and observers had hoped that Russia would slowly but surely converge in some ways with the United States. They predicted that once the Soviet Union and communism had fallen away, Russia would move toward a form of liberal democracy. By the late 1990s, it was clear that such an outcome was not on the horizon. And in more recent years, quite the opposite has happened: the United States has begun to move closer to Russia, as populism, cronyism, and corruption have sapped the strength of American democracy. This is a development that few would have foreseen 20 years ago, but one that American leaders should be doing everything in their power to halt and reverse.

Indeed, over time, the United States and Russia have become subject to the same economic and social forces. Their populations have proved equally susceptible to political manipulation. Prior to the 2016 U.S. election, Putin recognized that the United States was on a path similar to the one that Russia took in the 1990s, when economic dislocation and political upheaval after the collapse of the Soviet Union had left the Russian state weak and insolvent. In the United States, decades of fast-paced social and demographic changes and the Great Recession of 2008-9 had weakened the country and increased its vulnerability to subversion. Putin realized that despite the lofty rhetoric that flowed from Washington about democratic values and liberal norms, beneath the surface, the United States was beginning to resemble his own country: a place where self-dealing elites had hollowed out vital institutions and where alienated, frustrated people were increasingly open to populist and authoritarian appeals. The fire was already burning; all Putin had to do was pour on some gasoline.”

Bottom Line Question — Based on the Above:

Given that women, blacks, gays, etc., etc., etc., stand at the very center of the “change” controversies and conflicts that Fiona Hill and I describe above,

Should not more women, blacks, gays, etc., etc., etc., be placed exactly in positions and posts where they might more fully participate — and engage with and in — these such controversies and conflicts?

Note how — in the second quoted paragraph from Fiona Hill in my initial comment above — note how Hill points to:

“In the United States, decades of fast-paced social and demographic changes … had weakened the country and increased its vulnerability to subversion.”

Now consider that, in Felicia Wong’s article “Market Prophets: The Path to a New Economics” (also found in the current Nov-Dec 2021 issue of Foreign Affairs; therein, see Page 183), Wong points to these same “change” matters:

” ‘ The culture wars’ — as go to euphemism for the backlash against (the effort to achieve) racial and gender equality — could pull the United States away from acting on truly inclusive policies.”

(Item in parenthesis here is mine.)

Question:

a. If efforts to achieve such things as racial and gender equality “weaken the country and increase its vulnerability to subversion,”

b. Then should not special care be taken to place blacks, women, etc., in national security positions today and going forward; wherein, their advice on these crucial matters — which effects both themselves and our country most directly — might prove both exceptionally unique and exceptionally useful?

Let’s look at the issues raised in my initial comment above, in this case, through the post-Cold War national security point-of-view described in this excerpt from the Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law paper “Moral Communities or a Market State: The Supreme Court’s Vision of the Police Power in the Age of Globalization,” by Antonio F. Perez and Robert J. Delahunty; therein, see Pages 702 – 704:

” ‘Grutter’ reflects the (U.S. Supreme) Court’s deference to elite concerns in yet another way: not so much in forming a national elite that possesses ‘legitimacy in the eyes of the citizenry,’ as in meeting the business needs created by competition in ‘today’s increasingly global marketplace.’ The Court seems to have accepted the elite judgment that in order to remain vigorously competitive in the international arena, American business must select its leadership cadres from the entire range of racial and ethnic (and dare I say gender, sexual preference, etc., etc., etc.?) backgrounds found within the Nation’s population, so that the increased diversity within those cadres would at least roughly match the diverse population of the ‘global marketplace” at large. Elite formation would still be conducted in terms of ‘merit’-based selection principles, but ‘merit’ would now be defined in terms of a competitive advantage in an expanded, more thoroughly globalized, market. Thus, affirmative action, understood and applied in this manner, has fundamentally different goals from the Court’s Cold War-era project of desegregation. (Back then) desegregation served the needs of a Nation State that was attempting to be ‘the provider and guarantor of [individual] equality.’ In large part, desegregation was an effort to assimilate minorities into the dominant national group, thus forging a national people that could meet the external Communist enemy with a united front, and so denying that enemy any opportunity to exploit potentially dangerous rifts within the Nation. Affirmative action, as upheld in ‘Grutter,” is also thought to serve the Nation’s strategic needs, but in an international environment that is markedly different from the Cold War. No longer does the Court feel a need to foster a national unity that transcends racial (etc.?) consciousness or to further the assimilation of racial (etc.?) minorities. Such strategic needs have passed, together with the passing of the Cold War’s chief external threat. Thus the ‘Grutter’ Court could view the prospect of multiculturalism (etc.?) with equanimity despite the fact that, as Bobbitt correctly perceived, multiculturalism (etc.?) makes it ‘increasingly difficult’ for a Nation State ‘to get consensus on public-order problems and the maintenance of rule-based legal action.’ Rather than regarding the rise of multiculturalism (etc.?) as a liability that had the potential to weaken or even fracture the Nation, the Court saw it an an asset to be exploited for all the advantages it could bring American business in their international transactions. And again, race (etc.?)-conscious governmental actions is viewed through the prism of its usefulness, not its morality.”

(Items in parenthesis above are mine.) (Note that this paper is written in the year 2005.)

Bottom Line Question — Based on the Above:

Given that our post-Cold War pursuit of such “diversity” things as multi-culturalism, etc., have, indeed, proven to be (a) a boon for international business but (b) “a liability that had the potential to weaken or even fracture the Nation,” how now should we proceed?

In this regard, what would women, blacks, gays, etc. — if they were exceptionally more present in our national security positions today and going forward — what would they say?

Note how, in the quoted paragraph above, at least different three national security reasons are given for pursuing diversity; these being:

1. The “forming of a national elite that possesses legitimacy in the eyes of all its citizenry.”

2. To “meet the business needs created by competition in today’s increasingly global marketplace.” And:

3. The “forging of a national people that could meet the external … enemy with a united front … so denying that enemy any opportunity to exploit potentially dangerous rifts within the Nation.”

What appears to be glaringly missing from these thoughts, however, is an understanding that:

a. In pursuing such things as diversity,

b. One might not eliminate but, indeed, might CREATE and/or EXASPERATE dangerous rifts within the Nation; thus, CREATING an unique and powerful opportunity for an enemy to exploit same.