Role-playing games [can create] conditions for real-world cooperation

When I began my year at the U.S. Army War College (USAWC), I was looking forward to returning to an academic environment. I envisioned deep discussions about the latest thought in topics like economics and national security. And while there was plenty of great reading and discussion, it was a complete surprise to also go to class to engage in role-playing games. The USAWC games lacked the wizards and trolls of Dungeons and Dragons, but were, in their own fashion, even nerdier and more fun…at least for national security wonks. More importantly, they were a key component of my strategic education.

At the USAWC, the Center for Strategic Leadership (CSL) designs and runs a wide variety of games to help students and players from outside army organizations develop new perspectives on strategic problems confronting the United States. When combined with traditional scholarship, such as economic research, games become powerful tools to develop cooperative behavior between government agencies, the military, the private sector, and non-profits. This was certainly the case for me. My previous experience as an explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) officer overseeing de-mining operations inspired me to conduct my student research project on how the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) could use its mine action program to support U.S. and multi-national economic and security interests through a cross-sectoral, collaborative approach. My research identified numerous barriers to effective cross-sector cooperation and collaboration. One of the most significant was cost, meant here in all of its many forms to include risk. De-mining involves dealing with such a wide variety of partners — national and local governments, international non-profits, local citizens. Each of these different groups comes to a project with often wildly different quantities and kinds of resources and concerns. This disparity can often make it difficult to forge constructive working relationships.

A year at the War College allowed me to indulge my passion for economics. Though perhaps there might be a few individuals who do not share my enthusiasm for the “dismal science,” it would be a great mistake to dismiss its utility in understanding national security problems. Game theory is one branch of economics and social science research that can help form solutions to the kind of multiple agent problem described above. The “Prisoner’s Dilemma” is one of the most influential ideas drawn from game theory. Researchers use the Prisoner’s Dilemma to understand when and why people compete or cooperate in strategy development, implementation, and adjustment. In the dilemma, two prisoners undergoing separate interrogations must decide whether to either keep quiet (cooperate) and trust the other prisoner does the same, or to turn against their co-conspirator in order to get leniency for themselves (compete). Both prisoners get the best possible outcome if they stay quiet. If both confess, they each get the worst possible outcome. If only one confesses, the squealer “wins” but the one who keeps silent suffers harshly. Cooperation, therefore, yields the best possible outcome but requires the prisoners to trust each other to keep silent (cooperate). Without trust, they are moved to compete, lest they get punished for holding out while their fellow prisoner benefits from confessing. Given its focus on cooperation and competition, social scientists have used the Prisoner’s Dilemma model to research behavior in everything from arms control to medical treatments.

Towards the end of the academic year, I found an article published in the American Economics Journal: Microeconomics by Julian Romero and Yaroslav Rosokha, which provides useful insights that can be readily applied to the case of de-mining and other cross-sector relationships. They explored how cost (monetary in their research, but the concept could be extended to other factors such as time, lives, reputation) affects in-game strategy adjustments and cooperation during an indefinitely repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma game. During their research, Romeo and Rosokha found that in-game strategy experimentation led to an increase of cooperative behavior. Additionally, players made more in-game strategy adjustments towards cooperation when costs were low than when the costs were high.

While this seems intuitive, there are important implications for national security when we combine the two points: experimentation is crucial to fostering cooperation, but high costs (in any form) inhibit (though not prevent) experimentation. From a practical standpoint, during an actual operation, project, or other endeavor, organizations hesitate to adjust their strategies towards greater cooperation unless they can find ways to reduce the cost or risk of “in-game” adjustments or until another opportunity for experimenting “outside-the-game” develops. For example, the United States Institute of Peace highlighted the inherent reluctance of civil society organizations (CSOs) to coordinate with military units in Afghanistan, particularly the provincial reconstruction teams. However, the authors also noted CSOs’ desire to communicate with senior military leaders on matters of policy, especially as part of the planning process. Consequently, the USIP study concludes “an ongoing, high-level forum for civil society-military policy dialogue could help address tensions…and explore areas for possible collaboration such as in security sector reform.” Creating this forum would be a real-world application of Romero and Rosokha’s suggestion that we can foster cooperation by establishing a low-cost space for dialogue and strategy experimentation. A specially-designed role-playing game could provide such a forum for low-cost strategy experimentation and enable both CSOs and international military leaders to mutually determine the type of collaboration that is right for them.

At Carlisle, a variety of role-playing games provide students with a way to conduct low-cost, low-risk experimentation to develop cooperative strategies. CSL uses an assortment of role-playing games and exercises, to include subject-matter-expert-moderated matrix games, non-expert-led table top exercises, and LEGO Serious Play. The common aspect to all these game styles is the manner in which they stimulate dialogue and provide players the opportunity to develop, implement, and adjust their strategy throughout game play. I enjoyed both a matrix game examining security in the South China Sea and a table-top board game looking at China’s Belt-Road Initiative. Both games stimulated thoughtful discussion on the reasons for each team’s actions and reactions. In both games, strategies changed and evolved as teams reacted to conditions on the board and to dialogue among teams.

Social scientists have used the Prisoner’s Dilemma model to research behavior in everything from arms control to medical treatments

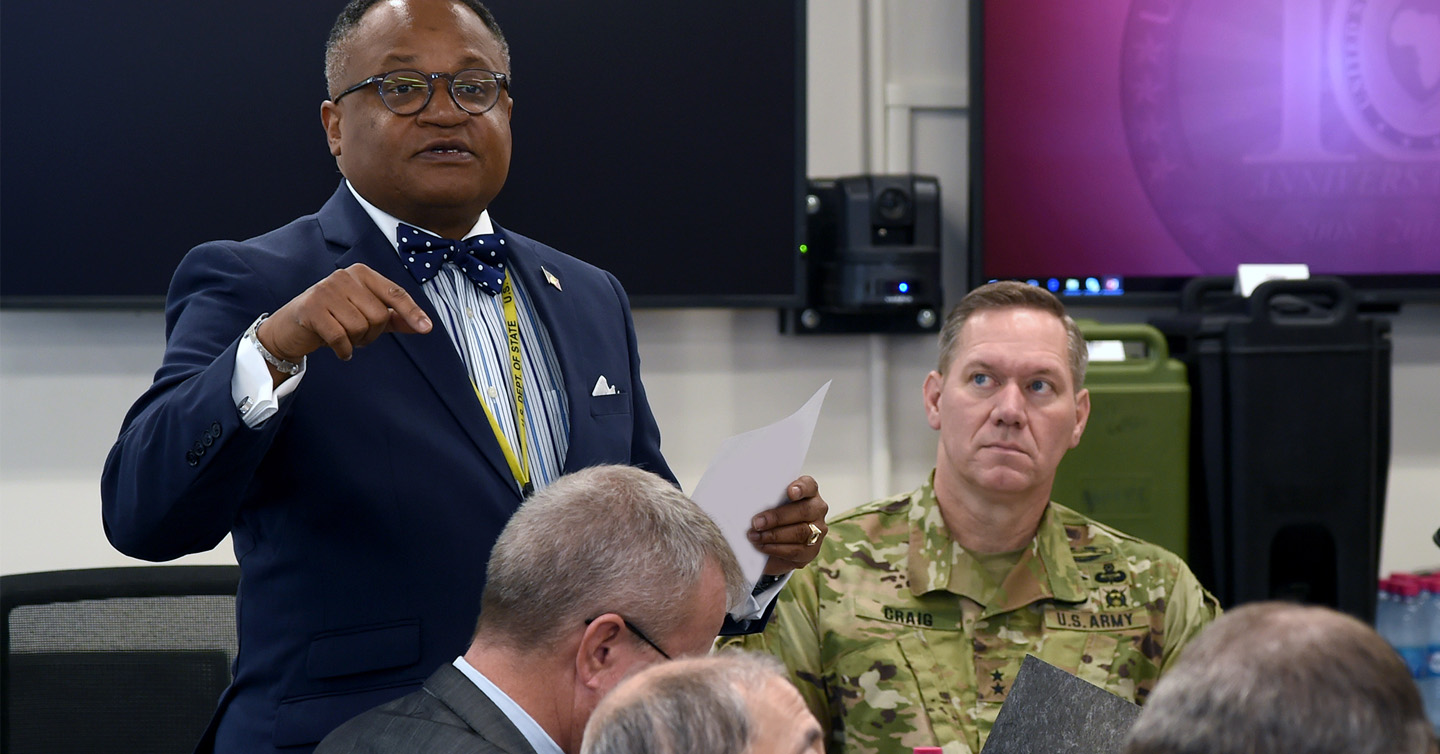

But to be most effective at generating cooperative behavior in the real world, players from the actual organizations and groups should physically come together for game play. When various interests are personally represented, role-playing strategy games provide a forum for disparate organizations to dialogue and test cooperative strategies without the cost — or risk — of experimenting “in-country” during an actual operation or program. This in-depth dialogue cannot be achieved without some means of lowering the cost for the respective groups.

Using my research project as an example, it would be possible for CSL to lower the costs of dialogue and strategy experimentation by designing a matrix game to explore interactions among international military forces conducting mine action, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), host-nation government agencies (including their militaries), and the local citizenry, as part of a holistic economic development plan. During each game round, all “teams” take a turn and state what they want to do and why. The other teams then articulate why they think the move would work or not. At that point, the moderator determines a probability of success and the required dice roll to achieve the proposed objective. During their turn, each team can respond to the other teams’ actions, whether cooperative or competitive. Most importantly, teams are free to communicate with each other throughout the round and in-between rounds, which allows them to generate cooperative ideas and strategies. The moderators can inject “wild card” events to challenge economic development and mine action programs, to which teams must respond during more dialogue and dice rolling. In each successive round, teams adjust their strategies based on inter-team dialogue and the evolving situation on the game board. In this manner, participants gain insight into the likely reactions of other participants, and, if desired, can adjust their strategies towards more cooperative behavior. Participants can then extrapolate the lessons learned from game play into the real world whenever the appropriate conditions for cooperation exist.

Admittedly, the notion that uncooperative organizations will magically open up, trust each other, and freely dialogue during a role-playing game is somewhat naïve. Again, infinitely repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma games provide the answer. A key premise behind infinitely repeated games is that no player knows when the game will end. Therefore, each player has an incentive to cooperate — or at least not stab the others in the back without weighing the consequences. As Masaki Aoyagi, V. Bhaskar, and Guillaume Fréchette noted in the February 2019 issue of American Journal of Economics: Micro-Economics, participants value the certainty of a long-term relationship when deciding to cooperate or not. At the risk of cliché: relationships do matter. The practical implication is that the role-playing game must take place over an extended period of time (e.g. 5 days) and on a recurring basis (e.g. semi-annually) so that participants build trust and overcome their reservations regarding cooperation. A one-day summit will not suffice.

Just as CSL routinely develops and conducts role-playing strategy games for general officers, USAWC students, and operational military units, it could create low-cost games to experiment with strategy changes outside the purely military environment. Additionally, the War College harbors several institutes with extensive experience working with cross-sectoral partners, particularly the Peacekeeping and Stability Operations Institute. DoD and other government agencies should use USAWC organizations to create and host role-playing games designed to explore and identify opportunities for cross-sector cooperation within a given topic area (e.g., election processes and institution building during peacekeeping operations) and invite cross-sector organizations to participate. Likewise, Department of State country teams and the combatant commands could invite cross-sector organizations and interests to participate in CSL-developed games designed to address country-specific problems (e.g. peacekeeping in Mali or civil-military partnerships in mine action and economic development projects in Vietnam). By creating such low-cost forums, U.S. government agencies — aided by USAWC expertise — can generate cooperative behaviors among a multitude of organizations that share mutual interests but that might not otherwise find a way to cooperate with each other.

Role-playing games and similar low-cost thought- and dialogue-based exercises can produce insights into and solutions for difficult national security problems, while also creating conditions for real-world cooperation. The USAWC — CSL, other institutes like PKSOI, and the student body — can assist operational units and interagency partners by combining such “experimental strategy” exercises with academic theory (like the “Prisoner’s Dilemma”) as in-class research or assignments. More importantly, however they are created and staged, security professionals should use dynamic gaming as a means to develop conceptual understanding, generate practical solutions, and foster cooperation in a low-cost game environment before implementing potentially costly and untested ideas in the real world. There is no dilemma here: “gaming” cross-sector collaboration is worth every penny not spent on untested strategies — especially when they fail for lack of forethought.

Shawn Kadlec is a lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army and a resident student of the U.S. Army War College class of 2019. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

Photo Credit: U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Nick Scott; from the Combined Joint Task Force-Horn of Africa website