What does it mean to “maintain the peace”? These aren’t simply semantic questions: Whose peace? Whose security? Whose rule of law?

Coercive force is used to maintain the social position and status of those who maintain the capability to employ it. The goal is usually to restore status quo ante. In the United States, this dynamic has played out recently in the narrative that pitted Black Lives Matter protestors against people sitting at home thinking, “what’s so wrong with the way things are?” And police forces were in the middle. Whom do police “serve and protect”? This same kind of story emerged again at the U.S. Capitol in early 2021 when police, prepared for a political protest, suddenly found themselves in the middle of riot aimed at overturning the existing political order. And again, Americans had to confront fundamental questions about the state’s use of force – or lack thereof. What does it mean to “maintain the peace”? These aren’t simply semantic questions: Whose peace? Whose security? Whose rule of law? In some respects, domestic policing is a good analogy for what the United States and other Western militaries have done internationally since World War II. Western soldiers have (at least rhetorically) been sent forth to “maintain the peace.” This mission necessarily supports the assumptions and structures that undergird Western society’s notion of what “peace” entails.

This use of Western militaries entails some cost. And Americans sure do spend a lot on their military. Maintaining a standing Army, for example, when the nation is not at war is an expensive proposition. If this military capability is to be maintained (and there is a strong economic, Constitutional, and strategic argument to made that it should not be, at least not it its current form), Americans should at least get some return on their investment.

When Americans discuss national military power and its use around the globe, what is the status quo that U.S. foreign policy should seek to maintain? “Great Power Competition” describes, perhaps, what is going on. The Powell/Weinberger doctrines perhaps describe when military force should be used. What really has been left unanswered is the why (or, more precisely, “to what end?”). There is a lot of talk about America’s lack of a grand strategy, but the necessary preliminary question—what should the goals of the strategy be—the “ends” in “ends-ways-means”—receives less attention, at least in military circles.

Like policing within the United States, the application of American military force abroad can be seen as a reflection of the American system and values. Every country acts in its own self-interest, but it would be a gross distortion to portray America’s reluctant involvement in world affairs as solely a bid for American domination of the globe for its own, selfish ends. Since World War II, the United States has sought to create an international legal and political order that is at least nominally based on a level playing field, fairness, equality, and opportunity to succeed for all nations. This is a description, of course, of the so-called “rules based international order” or “liberal international order”: the United Nations system (e.g., the Security Council, General Assembly, the United Nations Development Programme, the United Nations Childrens’ Fund (UNICEF), the World Health Organization, the International Labour Organization, and the Food and Agriculture Organization, and others), the Bretton Woods institutions (i.e., the World Bank, International Monetary Fund), as well as the World Trade Organization and Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), the European Communities (the European Economic Community, the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom), and the European Coal and Steel Community – now the European Union—arguably itself an American idea!) and the various other regional groupings designed to foster stability (Organization of American States, African Union, Council of Europe).

Preserving this larger, rules-based international order (RBIO) into which superpower America used its post-World War II position of dominance to bake in (small-“l”) liberal values, free from great-power bullying and subjugation of weaker nations by the strong, should be the object of the exercise. This is not a new idea. This overall system allows the maximum focus on growing the standard of living for all the world’s people, utilizes alliances to minimize the need for unilateral, massive military buildups, and ties nations into a stability-maximizing paradigm that keeps us focused on trade and away from value-destroying, debt-inducing, and people-slaughtering war. Ironically—but a fact that is very important in its own way—both Russia and China nominally recognize the legitimacy of almost all aspects of the international system, as well as the universal application of human rights and of democratic values, even if they do not take those values to heart and their actions may be, in fact, at odds with important aspects of the existing system’s basic rules.

American military power should be used in such a way as to demonstrate that the world’s liberal democracies are not so preoccupied with their own parochial concerns that they are unable to stand up for this rules-based international order. Such use is in America’s interests as this international stability will, in turn, let America spend more time and resources addressing bread and butter domestic concerns. “America’s interests at home are strengthened by improving lives globally.” Practically speaking, if the United States can ensure that the values it champions remain embedded in the rules-based international order, then it will have help in seeing that these values prevail. Many hands make light work.

What’s the biggest rule of this international system? The one that was implemented along with the founding of the United Nations. States must not change the borders of other states by force. The Charter of the United Nations outlawed offensive war. Before the 1928 Kellogg-Briand Pact, it was unarguably acceptable for a country to seek to expand its borders by conquest and an effort was made to change that in the aftermath of the Great War. The industrial-sized death machine of World War II had to happen before this ancient rule would definitively change. Supplanting the “might makes right” system with something fairer for smaller countries and more conducive to peaceful global cooperation was the crowning achievement of the 20th Century. And, although it might be difficult to see it sometimes, this change has largely been successful. There are still wars and violence – the late twentieth century and early 21st wrought proxy wars, civil wars, terrorism, and genocide. Vietnam, the Gulf War, Rwanda, 9/11, Syria. But these have largely been the tragedies of global superpower peace, not the all-consuming conflagrations of global war. The difference is one of scale: conflicts have been limited geographically, financially, and in terms of human life (although the impact on individual lives, families, and communities even in “limited” conflict is undeniable). Conflict and war are constants in human existence—there is no version of human relations on this planet where all conflict is avoided and the number of victims of armed conflict approaches zero. Thus, limiting conflict is the best worst alternative. All deaths in war are regrettable. That said, keeping direct military conflict at a low boil is, arguably, a positive achievement even if some military conflict does, inevitably, continue. Avoiding devastating global conflagration—even in favor of destructive, smaller wars—is an enormous good—even though that rational argument is difficult to accept from an emotional, affective point of view.

Russia is currently acting beyond all the Post-War norms of conduct and needs to be shown what the necessary limits to her behavior are.

In the current environment, if the broadest goals of using military force are to preserve life, prevent escalation to world war, and to preserve the RBIO, then safeguarding high-impact conflict zones means demonstrating to Russia that the United States’ attention on China doesn’t mean it is open season on the middle countries of Europe. Hopefully, in the aftermath of WWII the world realized the costs of letting the great powers try to rip up and destabilize the smaller countries situated in between them. Russia is currently acting beyond all the Post-War norms of conduct and needs to be shown what the necessary limits to her behavior are. Even Russia’s predilection for bilateral, great-power negotiations harkens back to an earlier era where smaller countries were carved up by empires with the countries being dismembered having no say in their own fate.

Ukraine is a good example for the United States and the West to make this point. Readers will have to determine for themselves the state of the Russian invasion of Ukraine at the time they read this. Already having been invaded by Russia in 2014 in Crimea and the Donbas, showing resolve in Ukraine would simply involve using military force in a way that is reciprocal to Russia’s use of military force. Mass troops on your own territory and call it an exercise? Position support forces that could be used to enable an invasion? NATO can do all that on the Polish (and Lithuanian) borders of Kaliningrad just as easily as Russia did so on Ukraine’s border.

If Russia makes similar threats against Poland, the Baltics, or other NATO members in eastern Europe as it is currently executing in Ukraine (and, to be fair, it is simply a matter of time until she does so), this reciprocity shifts from being advisable to becoming absolutely necessary to preserve the viability of the Atlantic alliance. Not only is an ounce of prevention better than a pound of cure, but the military advantage of a defender over an attacker is also well understood. Garrisoning an ally is immeasurably less costly than liberating them, and much more effective. Robust, sustained, and multi-domain direct assistance to Ukraine as well as international sanctions against the aggressor (perhaps, for domestic political reasons—as well as for the purpose of maintaining a lockstep international alliance and avoiding an early start to World War III—short of entering the war against Russia as a belligerent) also contributes mightily to keeping Russia in check and preserving the rules-based system.

Taiwan is nowhere near as good an example for the United States and allied nations to use to prove their commitment to a rules-based international order. The legal situation is much less clear and, in fact, favors the Chinese position. Although the U.S. has every interest in maintaining the democratic regime in Taiwan, unlike the situation in Ukraine—a sovereign country where Russian encroachment is almost universally accepted as legally wrong—no one seriously argues that there is more than one country named China. No one. Not the government of the People’s Republic of China in Beijing, not the government of the Republic of China in Taipei, and not the government of the United States in Washington D.C.. There was a time when the U.S. and the West wanted the R.O.C. government to continue to rule all of China, but the R.O.C. lost that war militarily and, later, diplomatically. The R.O.C. later retreated to the island of Formosa. If Beijing wanted to re-take the island, however regrettable for the Chinese people living there (and for the prospect of continuing to demonstrate that Chinese people can prosper under a democratic government), the case for preventing it from doing so is much less compelling. Given China’s obsession regarding the country’s territorial integrity, this is both a strange hill for America to die on and also puts China on the same side as Ukraine in the ongoing dispute with Russia, at least intellectually. In short, the Taiwan situation doesn’t impact the rules-based international order. The Taiwan situation falls squarely on the “great power competition” side of the ledger.

Specific examples aside, this overall prescription of the principles that should underlie the use of American military power nests nicely with the current guidance, which emphasizes “… [1] protect[ing] the security of the American people…[2] expanding economic prosperity and opportunity, [and 3] realizing and defending the democratic values at the heart of the American way of life.”

In particular, the appropriate use of the American military is reflected by the three pillars of the current national security strategy, with one pillar directly speaking to the defense of the international legal order:

“At its root, ensuring our national security requires us to:

- Defend and nurture the underlying sources of American strength, including our people, our economy, our national defense, and our democracy at home.

- Promote a favorable distribution of power to deter and prevent adversaries from directly threatening the United States and our allies, inhibiting access to the global commons, or dominating key regions; and

- Lead and sustain a stable and open international system, underwritten by strong democratic alliances, partnerships, multilateral institutions, and rules.”

The administration’s current strategic guidance reflects an admirable preoccupation—shared by leading military thinkers and by those on both sides of American politics—with alliances and international collaboration, reflecting how all nations that aren’t China or Russia have an interest in curbing the appetites of proto-imperial proto-superpowers.

The American experiment must be in service to larger principles and the rule of law; a regime that simply seeks power to decisively compete with others is unworthy of Americans’ support. If we can, therefore, agree on the principles that should underlie the use of American military force, what remains is to bear in mind this why both when considering grand strategy and when engaged in detailed planning for the use of American military force in pursuit of that strategy. This is imperative is not just for policy makers, but also for military commanders and planners. The why informs the how, often decisively. And the military tends to pay less attention to the why than it should.

“He who has a why to live for can bear with almost any how.”

Garri Benjamin Hendell is a major in the Pennsylvania Army National Guard. He has three completed overseas deployments to the CENTCOM area of operations, three overseas training missions to Europe, leadership and staff positions at the platoon, company, battalion, brigade, division, and joint force headquarters level, as well as having served both in uniform and as a civilian branch chief at the National Guard Bureau. Among other things, he is a graduate of the Army’s Red Team course.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

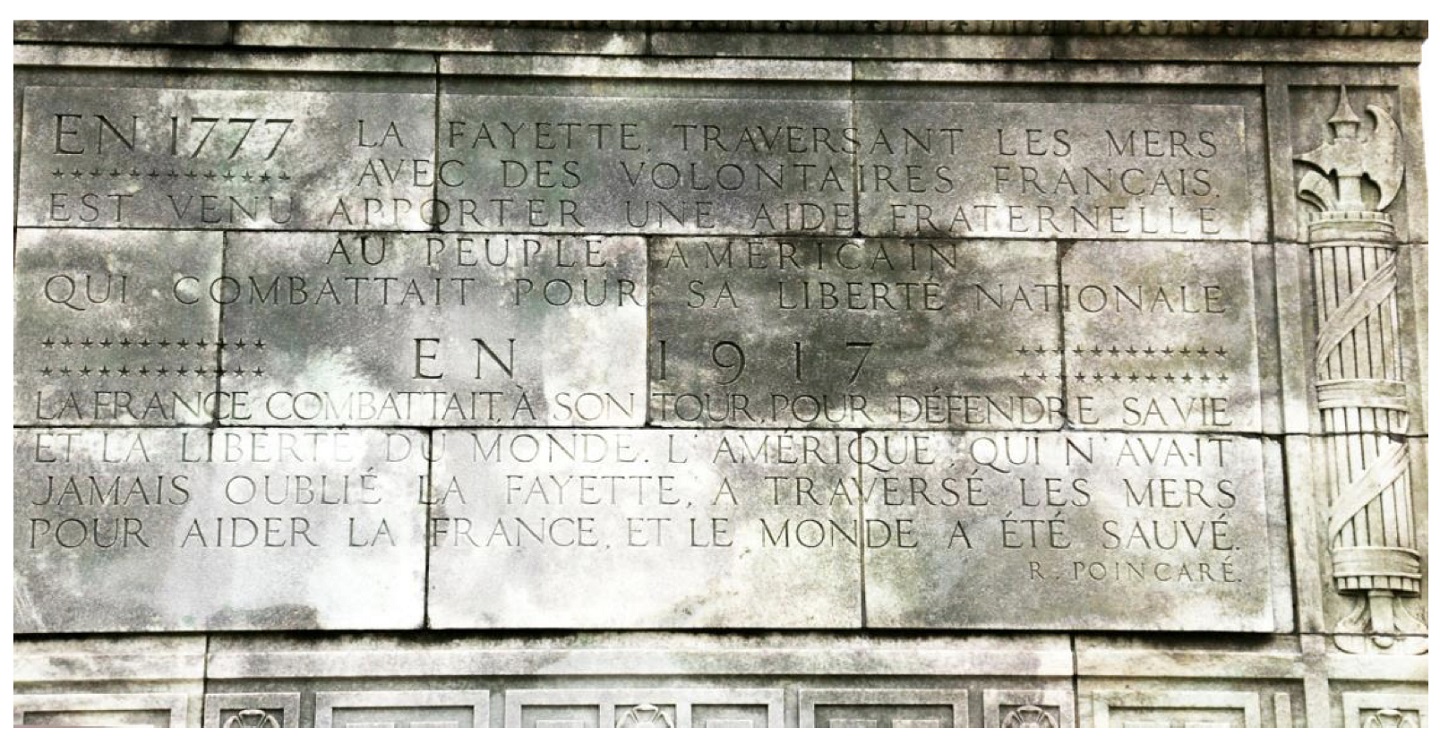

Photo Description: The inscription on the Lafayette monument (Base, east side) in Baltimore, MD. Roughly translated it reads “In 1777 Lafayette crossed the seas with French volunteers to lend fraternal aid to the American people who fought for their national freedom. In 1917 France fought, in her own turn, to defend her life and her freedom and the freedom of the world. America, who never forgot Lafayette, crossed the seas to assist France, and the world was saved.” R. Poincairé

Consider this as the “why:”

So that the citizens of the U.S./the West — and the citizens of other states and societies also — can pursue and acquire “life, liberty and estate” (John Locke.)

Re: my suggested — Lockean — “why” “prime directive” noted immediately above:

a. If we were to consider the questions “what are the guns for” and “why would we deploy them;” if we were to consider these question from the perspective of “globalization” providing the citizens of the U.S./the West — and the citizens of other states and societies also — with a better way to pursue and achieve “life, liberty and estate,”

b. Then, from that such perspective, might we say that “what the guns are for” and “why would we deploy them,” this would be to (a) help facilitate and support globalization and, thus, to (b) stand hard against those individuals and groups (both in one’s own home country and abroad) who would stand in the way of globalization?

Problem No 1: One problem here being, of course, that (a) while, arguably, globalization does provide one’s citizens with a better way to pursue and achieve “life, liberty and estate,” (b) globalization does not do this without cost. This cost being that globalization requires that one’s government actively pursue and achieve certain “revolutionary” political, economic, social and value “changes” — both in one’s own home countries and abroad — this, so that globalizations’ better “life, liberty and estate” promise might be realized.

Problem No. 2/Related Problem: As can be seen from my quoted items immediately below, certain population groups both here at home (see my first quoted below) and there abroad (see my second quoted item below) resist and reject these such — globalization-required — “revolutionary changes:”

“Liberal democratic societies have, in the past few decades, undergone a series of revolutionary changes in their social and political life, which are not to the taste of all their citizens. For many of those, who might be called social conservatives, Russia has become a more agreeable society, at least in principle, than those they live in. Communist Westerners used to speak of the Soviet Union as the pioneer society of a brighter future for all. Now, the rightwing nationalists of Europe and North America admire Russia and its leader for cleaving to the past.”

(See “The American Interest” article “The Reality of Russian Soft Power” by John Lloyd and Daria Litinova.)

“Politically, in many cases today, the counter-insurgent represents revolutionary change, while the insurgent fights to preserve the status quo of ungoverned spaces, or to repel an occupier – a political relationship opposite to that envisaged in classical counter-insurgency. Pakistan’s campaign in Waziristan since 2003 exemplifies this. The enemy includes al-Qaeda-linked extremists and Taliban, but also local tribesmen fighting to preserve their traditional culture against twenty-first-century encroachment. The problem of weaning these fighters away from extremist sponsors, while simultaneously supporting modernisation, does somewhat resemble pacification in traditional counter-insurgency. But it also echoes colonial campaigns, and includes entirely new elements arising from the effects of globalisation.”

(See David Kilcullen’s “Counterinsurgency Redux.”)

Bottom Line Thought — Based on the Above:

“Policing/Maintaining the Peace” — thus today from both a domestic and an international point of view — to be seen from the perspective of dealing with/standing hard against those individuals and groups, found both here at home and there abroad, who resist/reject such political, economic, social and value changes as are needed; this, so as to provide that, via globalization, our citizens, and the citizens of other states and societies, might better pursue, and better acquire, such things as “life, liberty and estate?”

With regard to my thought above, Andrew Bacevich’s — 1999 — “Policing Utopia: The Military Imperatives of Globalization” came to mind. Here is an excerpt from Page 9, in the major sub-section therein entitled “The Strategy of Globalization:”

“This removal of barriers and borders is a development of singular importance. As Sandy Berger, the President’s national security advisor has remarked, ‘We have experienced the emergence of a global economy and a cultural and intellectual global village.’ The priorities implicit in that state are not accidental. The promise of globalization is first of all economic. An open, integrated world implies unprecedented opportunities for the creation of wealth. In its very essence, globalization heralds the enticing prospect of vast new and expanding markets.”

(As the title of COL [ret.] Bacevich’s article above indicates “policing/maintaining the peace” — this, in the age of globalization — this is THE job that must be taken on. This, if we are to “life, liberty and estate” benefit from those “vast new and expanding markets” he notes above?)

As to the matters presented in our article above, the following may be an interesting question. Here goes:

If, during the Old Cold War of yesterday, the U.S./the West developed and deployed its military, police and intelligence assets; these, often to deal with the more liberal/the more pro-change elements of the states and societies of the world (those both here at home and there abroad); elements, thus, who often EMBRACED “revolutionary” political, economic, social and value “change” (as required by communism back then),

And if, during the New/Reverse Cold War of today, the U.S./the West has developed and deployed its military, police and intelligence assets now; these, often to deal with the more conservative/the more no-change elements of the states and societies of the world (those both here at home and there abroad); elements, thus, who REJECT “revolutionary” political, economic, social and value “change” (as required by capitalism, globalization and the global economy today),

Then what common “why” (the Lockean “prime directive” noted in my earlier comments above?) might explain both of these such phenomena?

TLDR…

Conciseness and coherence are both virtues.