He was a competent but not flamboyant officer, commanding at an echelon that attracted little public attention during and after the war.

In recent years there has been much discussion about the Army’s refocusing on largescale combat operations, command at the division echelon, and the transformation of the National Guard from a strategic to an operational reserve. One book from the Dusty Shelves of interest for these issues is John Kennedy Ohl’s Minuteman: The Military Career of General Robert S. Beightler, the story of a wrongly forgotten commander from World War II.

Beightler commanded the Ohio National Guard’s 37th Infantry Division from 1940 to 1945. He was the only Guard division commander in the Second World War to lead his unit from mobilization to demobilization. Beightler remained in command because his skills, and his ability to learn from experience, carried him through the unforgiving general officer assessment process instituted in 1940 by the Army’s chief of staff, Gen. George C. Marshall, and insulated him against the fierce anti-Guard prejudice of Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair, the head of Army Ground Forces. Sent to the Pacific in 1942, the 37th operated in jungle, urban, and mountainous terrain, building a reputation as one of the best Army divisions in that theater. After the war, Beightler was one of two Guard general officers offered a commission as a Regular Army general officer.

This achievement remains obscure for several reasons. Beightler never published a memoir. He was a competent but not flamboyant officer, commanding at an echelon that attracted little public attention during and after the war. In the Pacific theater, fame gravitated towards either the Marine Corps or Douglas MacArthur. Postwar, the Army favored its European experiences for inspiration and historical study. Everybody knows Patton. Everybody should know about Beightler, too.

Beightler was both a typical and an atypical senior guardsman in 1940. Typically, he was a son of white, politically conservative small-town America who became successful in his civilian career. That success gave him the time and money to pursue a second career as a Guard officer. He entered professional, political, and military networks that assisted his advancement in all three spheres. Beightler developed a deep emotional investment in the Guard and shared the widespread belief among his peers that almost all Regulars disdained them.

What made him atypical was his drive to prove himself the equal of Regulars. He served with an Ohio unit during the First World War. The purge of Guard general and senior field grade officers during the war convinced him the same thing would happen in the next war unless guardsmen fully prepared themselves. In 1926 he took the Command and General Staff School’s three-month reserve components course. As the 37th Division’s G-2 intelligence officer, he attended the Army War College’s course for G-2s. After returning from France, Beightler had worked for the Ohio Department of Highways and was a partner in a road construction firm. In the early 1930s the federal government greatly increased its funding for highway construction and Beightler’s expertise in this field secured for him one of the reserve component positions on the War Department General Staff. The Army in 1922 had prepared an outline of an interstate highway system to serve military needs. Beightler updated this plan, recommended priorities for construction, and served as the War Department liaison with the Bureau of Public Roads. Accepted for what was normally a six-month detail, Beightler so impressed successive heads of the War Plans Division that he served there for four years.

What he did not have before mobilization was experience as a commander. His first command was an infantry brigade in 1940. A month after taking it, Ohio’s governor selected him to lead the 37th when its commander failed the pre-mobilization medical examination. Less than a month after taking command of the division he led it into federal service. Although Beightler left a relatively meager collection of personal papers, among them are letters to his wife in which he provides candid remarks about his superiors, subordinate commanders, and staff. These letters, together with memoirs, interviews, and official records, allow Ohl to detail how Beightler prepared the 37th and then commanded it in combat.

I am loath to order them into battle without considerable training in the methods of warfare peculiar to our situation…I want all of my men as well prepared as possible for the difficulties to come.

For example, in 1944 Beightler was looking for a new assistant division commander. He wrote his wife that the XIV corps commander had sent him two brigadier generals to look over. “One impressed me not at all. The other I thought I could use. But then it turned out that he was an alcoholic and with one regimental commander to combat with in that field I decided against taking on a drunken BG.” After the costly battle for Manila in 1945, the division paused to integrate replacements and prepare for the advance into mountainous northern Luzon. Beightler wrote an old friend “I am loath to order them into battle without considerable training in the methods of warfare peculiar to our situation…I want all of my men as well prepared as possible for the difficulties to come.”

The nineteen months between mobilization and deployment was a period of intensive on-the-job training. Beightler’s experience managing the Ohio Department of Highways had prepared him for the administrative responsibilities. He learned quickly from his mistakes during the first division-level field training exercise in 1941 and became a capable tactician. Seeing himself as a fellow citizen-soldier, Beightler moved easily among his troops. His obvious competence, attention to soldiers’ welfare, and frequent appearances on the front line made him highly regarded within the 37th. By the time the division landed on Luzon in 1945, many i of its members referred to Beightler as “Uncle Bob.”

The most important lesson in these nineteen months was insisting on high standards and relieving officers who could not meet them. For Beightler, firing subordinates—especially fellow guardsmen whom he had long known—was a painful duty, but one he continued to fulfill once the division entered combat. He then delegated extensively to those leaders who did meet his standards. Providing his soldiers with the best possible leadership, he understood, was the foundation for the division’s performance and for his remaining its commander. He took the same care with providing himself competent assistants on the division staff.

As the war went on, Beightler became increasingly frustrated by what he saw as senior regular officers’ shabby treatment of him and other guardsmen. Ohl notes that this resentment led him to sometimes ascribe to prejudice what was normal Army practice. Nevertheless, that prejudice did exist; even his Regular Army assistant division commander disdained his Guard superior. In 1943, Beightler wrote his wife that “I have to watch every move for a civilian component officer is behind the 8-ball from the start and one little mistake means that he’s out, whereas a regular army officer making a similar error would probably be given another chance.” Only in Maj. Gen. Oscar W. Griswold, the XIV Corps commander, did he encounter a regular general officer who treated him as a fellow professional.

Much is different from when Beightler led the 37th into federal service nearly eighty years ago. The National Guard has become an operational reserve, precluding lengthy post-mobilization training periods. Technology has changed and continues to change the conditions of large-scale combat and the methods of divisional command. Nevertheless, some things remain the same. The National Guard’s dual nature. The tensions between components. The importance of professional competence. The human interactions shaping relationships between leaders and subordinates. The leader’s responsibility to set and enforce high standards. The moral courage to relieve subordinates who cannot fulfill their duties. Robert S. Beightler’s military career, as John Kennedy Ohl’s Minuteman so well shows, still offers insights in all these areas.

William M. Donnelly is an Army veteran of the Persian Gulf War and a senior historian in the Histories Division, U.S. Army Center of Military History. He is the author of Under Army Orders: The Army National Guard during the Korean War and We Can Do It: The 503d Field Artillery Battalion in the Korean War. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

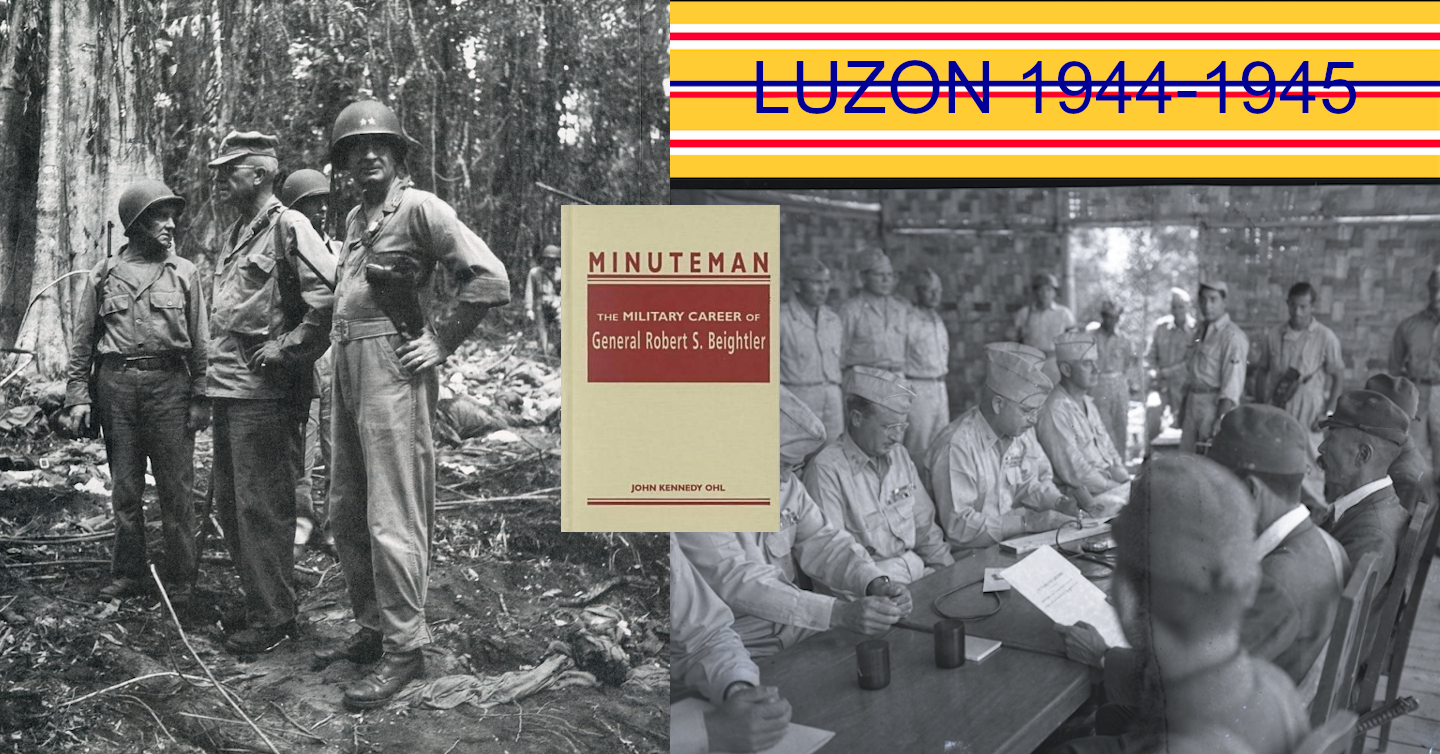

Photo Description: Left, Major General Robert Beightler in the field with his men. Right, Major General Beightler, Commanding General, 37th Infantry Division accepting the articles of surrender from Major General Iguchi, Commanding General, 80th Brigade, Imperial Japanese Army, Tuguegarao, Luzon, Philippines, September 5, 1945.

Photo Credit: U.S. Army Photos from the Beightler Collection at the Ohio Historical Society.

Other releases in the “Dusty Shelves” series:

- KOREA ON THE BRINK: GENERAL JOHN WICKHAM AND POLITICO-MILITARY CRISIS MANAGEMENT

(DUSTY SHELVES) - FIGHTING BY MINUTES, THIRTY YEARS LATER

(DUSTY SHELVES) - THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER (1988): THE FORGOTTEN PRIMER ON LEADERSHIP

(DUSTY SHELVES) - RIDGWAY’S KOREAN WAR

(DUSTY SHELVES) - ALL WAR IS LOCAL: ANTHONY QUAYLE’S EIGHT HOURS FROM ENGLAND

- POST-WAR TRUTH TELLING: THE WAR MANAGERS

- DYE: EXALTING THE TAIL OF THE AIRPOWER TOOTH

(DUSTY SHELVES) - PEACE FORMS: LOOKING BACK TO THE FUTURE OF WAR AND ANTI-WAR

- SHERMAN: THE OUTLIER OF INTERWAR “ATLANTIC” AIR THEORY?

(DUSTY SHELVES) - STRUGGLING TO SEE THE FUTURE: UNLESS PEACE COMES

(DUSTY SHELVES)

Hi Friends at U.S. Army War Room; Joseph P. Donnelly, here;;;;networking The WYLD DONNELLY’s. I am trying to get a message to William M. Donnelly’ U.S. Army veteran and historian; courtesy to; my project; THE SALEM WITCH PROJECT. P/T: 857-205-7134