Better Army recruiting will yield a healthier force structure

Recruiting is critical for sustaining the All-Volunteer Force. Under U.S. Federal Code Title 10, each service performs its own recruiting function. Unlike the Air Force and the Navy, who measure themselves based on their numbers of platforms, the Army measures itself on its end strength, both in terms of structure and in the ability to fill it. In practice, however, increasing the former does not assure the latter. For example, former Secretary of Defense Mattis prioritized a “modest increase” to the Army’s end strength for FY19, to add 11,500 soldiers. While this sounds like a good thing for the Army, it placed tremendous pressure upon the U.S. Army Recruiting Command (USAREC), to find and recruit that many individuals with the requisite qualities for service. At the same time, the Army could not afford to grow USAREC to meet the recruiting mission, as every soldier serving as a recruiter takes a soldier away from fighting units. So how does the Army grow to its targeted end strength without increasing recruiters? Regardless, it must do so as efficiently as possible.

The acceptability of these efficiencies boils down to the need to incur cost and to shift talent, but with the Army’s failure to achieve its recruiting mission in FY18 by about 6,500 enlistments, during a period of low unemployment — which further reduces the number of eligible applicants, the Army is more likely to accept these expenses. The reality is that the Army must be willing to invest more to meet its force structure requirements. At least four initiatives can be implemented to optimize Army recruiting efforts: (1) seeking congressional assistance to widen the candidate pool; (2) expanding the Total Army Involvement in Recruiting (TAIR) program, to incentivize soldier referrals; (3) leveraging enterprise-level contractors for future soldier management; and (4) retaining centrally-selected recruiting battalion commanders for three years.

Widening the Candidate Pool

Working with the U.S. legislature to mandate selective service for females may dramatically improve the Army’s ability to achieve its desired force structure ends. As a federal judge recently ruled an all-male draft unconstitutional, the time is ripe for Congress to mandate selective service for women. Doing so could double the candidate demographic. Selective service sows the first seed, fostering an awareness of the profession of arms as a viable occupation for those who would not otherwise have the exposure to it. The Department of Defense estimates the current male-only selective service process generates approximately 75,000-85,000 recruiting leads annually. Opening selective service would naturally double the volume.

Soldier Referral Program

Even with an expanded pool of applicants, all within the military must shoulder the recruiting effort. The Total Army Involvement in Recruiting (TAIR) program supports “promotional activities” for recruiting efforts. However, the TAIR can be better modified to provide incentives for Regular Army and Army Reserve Soldiers to help more directly and tangibly in those efforts. Social media databases can be created for soldiers to provide enlistment referrals, incentivized through the prospect of earning Certificates of Achievement, coins, or Army Achievement Medals. Adding a ‘Soldier Referral Program’ under the TAIR umbrella could make the program a truer, fuller representation of “Total Army” recruitment, which rewards individual efforts to recruit and which amplifies a mindset of pride in the profession of arms.

Every soldier serving as a recruiter takes a soldier away from fighting units

Outsourcing Some of the Accessions Process

The military industrial base presents a mechanism to optimize recruiter workload. About 1400 Army recruiting centers exist worldwide, and each of these assigns an individual recruiter to be a Future Soldier Leader (FSL), with full or part-time responsibilities to monitor the development and commitment of all future soldiers—that is, contracted enlistees awaiting assignment to basic training. This further translates to fully or partially degraded recruiting capacity within each center, as the assigned FSL then has less time and opportunity to conduct other recruiting responsibilities. Assuming this FSL’s responsibilities are degraded on average by 50%, or a loss of roughly 12 additional enlistment contracts per year, this responsibility equates to a total potential loss of an additional 16,800 enlistments across all centers. USAREC can gain greater efficiency by contracting individuals with non-commissioned officer experience from local U.S. Army Reserve and National Guard units to help manage these future soldiers, with limited responsibilities focused on non-recruiting requirements, in lieu of trained recruiters.

Stabilize Leaders in the U.S. Army Recruiting Command

In addition to optimizing the generating force, the Army can gain tremendous volumetric growth in mission requirements through leadership alone. Centrally-selected recruiting battalion commanders spend the bulk of their first year in command developing their understanding of the nuances of business, marketing, and local networking. Recent initiatives to install successful tactical battalion commanders into a second command within recruiting will garner marginal results. Although no empirical data exists, general consensus within the recruiting world reflects an understanding that recruiting battalions experience massive improvements in a battalion commander’s second year of command. Wisely, the U.S. Marine Corps selects its very best majors to command recruiting stations for a three-year period. The Army would be well-served to emulate this standard at the battalion command level. By harnessing this leadership, network development, and mission comprehension for an additional year of command, the Army could yield immense dividends in innovation, doctrinal practice, and mission success, rather than repeating the same two-year swing in performance under a “proven” tactical leader.

Change is Needed

The Army must grow without growing its recruiting structure, but change is never easy. However, better Army recruiting will yield a healthier force structure, by ensuring that both the right quantity and quality of throughput enter the force up front. With a dwindling pool of eligible applicants and increased expectations to meet mission requirements, creative solutions are in order. The Army will gain greater efficiency and optimize the generating force through congressional legislation to expand the pool of applicants, a modified Total Army Involvement in Recruiting program, enterprise-level contractors, and sustained leadership. In doing so, the Army will succeed in the recruiting mission, while rebalancing force structure allowance. Ultimately, recruiting changes that yield end strength improvements can achieve desired force structure ends and preserve flexibility for future growth.

Vylius Leskys is a colonel in the U.S. Army and a graduate of the U.S. Army War College resident class of 2019. The views expressed in this article reflect those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

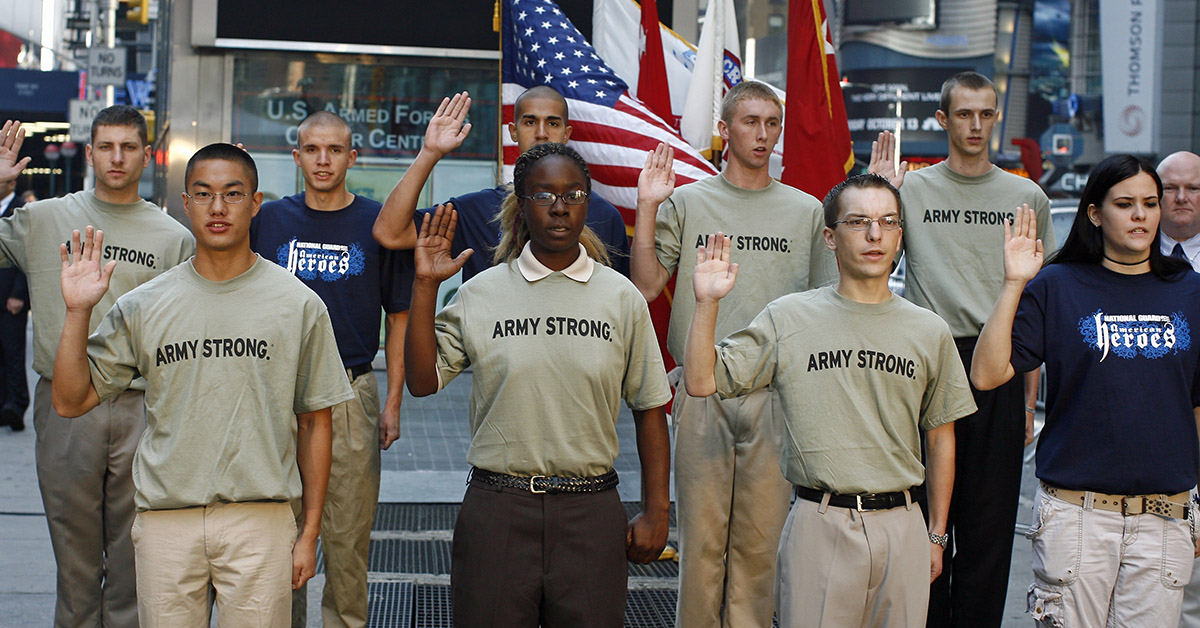

Photo: Nine recruits take the oath of enlistment during a cermony at the Times Square Recruiting Station, New York City.

Photo Credit: U.S. Army photo by SFC Jennifer Yancey