Digging deeper, we noticed that the U.S. and British principles of war, as they stand, did not adequately address the notion of competition as part of the changing character of war in the 21st century

Military leaders in the United States and United Kingdom have been consistently using the term “competition” to describe the national security relationship with Russia and China. As students in the same seminar at the U.S. Army War College, we were confronted with the dilemma of trying to identify a clearly articulated strategic purpose of competition to inform discussion and develop national security strategies. The big question is, what, exactly, is the United States, United Kingdom, and the West competing for? Military dominance? Liberal world order? Economic status? Digging deeper, we noticed that the U.S. and British principles of war, as they stand, did not adequately address the notion of competition as part of the changing character of war in the 21st century. This short article, aimed at national security professionals on both sides of the Atlantic, proposes a strategic aim of competition and new supporting principles of war as a means for further discussion and ultimately, resolution.

The Biden Administration’s U.S. Interim National Security Guidance and the U.K.’s Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy, two equivalent documents published in early 2021, both highlight the risks to the rules-based international order (RBIO) by adversaries such as Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea operating within the so-called “grey zone” between war and peace. Additionally, more recent military focused doctrinal concepts such as the U.S. Joint Concept for Integrated Campaigning (JCIC) and the U.K. Integrated Operating Concept (IOpC) have also demonstrated the need to address “grey zone” challenges. These strategies and concepts, however, do not clearly articulate the purpose or goal of the competition. We propose that the aim of competition, in the context of national security and foreign policy, is to gain and retain access and influence to preserve a RBIO favourable to the West. While today’s RBIO was established by the West, it has also been favourable to prosperity across the globe given its focus on a free-trade system with expanding economic prosperity, cooperation and international law to solve problems, and the spread of democracy. Access and influence set the conditions to pursue interests, enables democratic discourse, and provides economic assurance and security that rests on the foundation of the current RBIO.

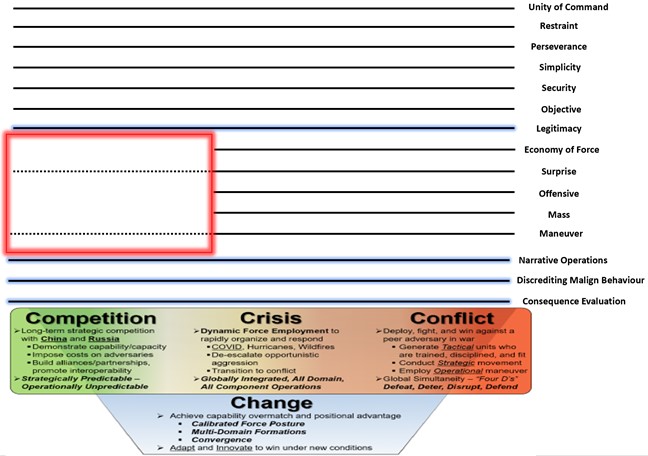

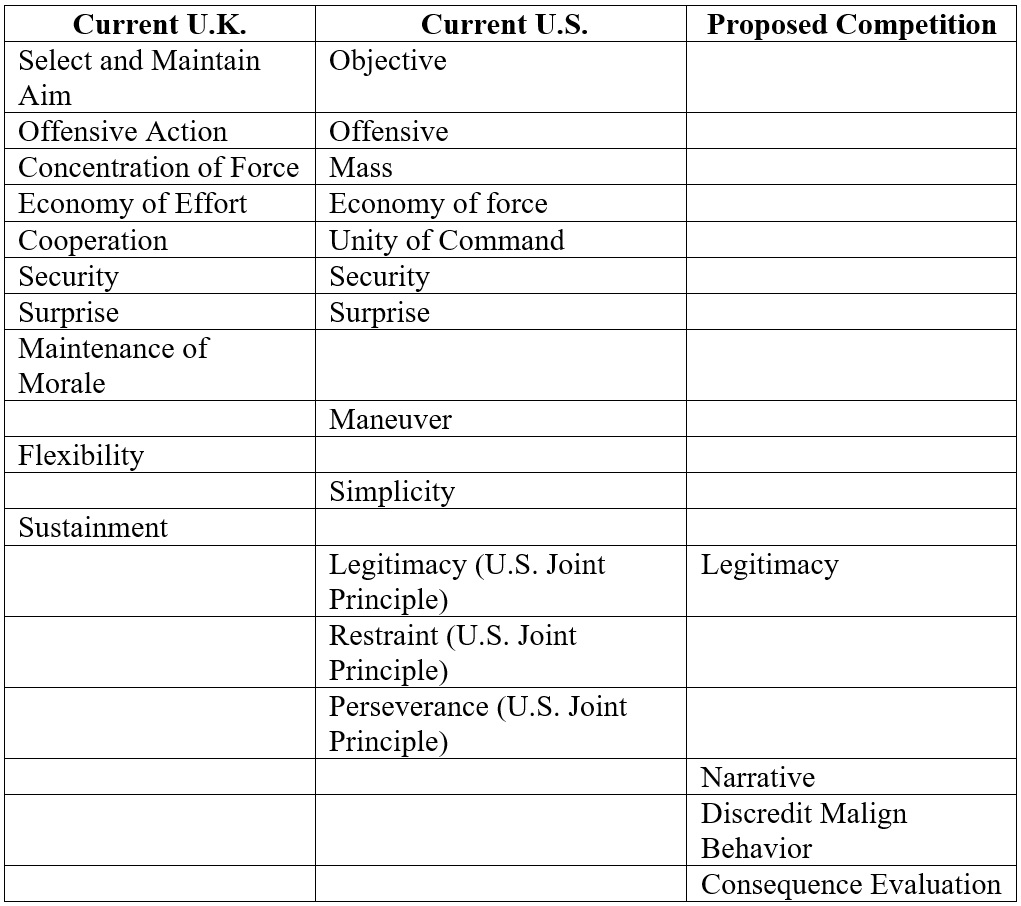

Malign actors, who use a broad range of means, including cyber-attacks, proxies, state-sponsored economic warfare-type activities, and disinformation to achieve their ends below the level of armed conflict, exploit the seams in the Competition Continuum (see Figure 1) to disrupt access and influence. The U.S. and British principles of war, which have remained largely unchanged since the 1920s, merit review as the character of war has changed significantly over the last 100 years. War is increasingly lethal, connected, and rapid. The distinction between war and peace is more ambiguous, the barriers to technology with military application lower, and the speed of change in the operating environment faster.

Principles of war act as guideposts for military leaders and are relevant at every level of war. Similarly, they now must be germane across the Competition Continuum. This expansion of application is not farfetched. Militaries already seek to apply the principles of war in competition, before and during armed conflict. For example, during humanitarian relief and peacekeeping operations, militaries create structure to achieve unity of command and use economy of force to position forces according to primary and secondary efforts. Also, in competition, militaries position for surprise as well as for future maneuver. Deciding whether new principles are incorporated as principles of competition, such as joint operating principles in U.S. Joint Publication 3-0, or as additional principles of war is not crux of the problem. Providing military leaders the tools to think about how to fill the gap evident (see Figure 2) in competition is the core challenge. Without addressing this gap, militaries will continue to position for success in war while losing in competition with malign actors continued exploitation of this gap between war and peace.

There is a growing body of literature challenging the veracity of the current principles of war given the changing context and character of warfare. Much of this work validates the principles as they stand, a few offer minor modifications or the addition of contemporary principles and fewer still recommend a sweeping change. These various works focus on conventional war and, occasionally, unconventional warfare. However, because of the rapidly changing character of warfare, driven largely by the malign behavior of revisionist states below the level of armed conflict, the national security community recognizes that the distinction between peace and war is more clouded than it has been in the last century.

If the purpose of competition is for access and influence to preserve a RBIO favorable to the West, the principles of war as they stand appear stale. The authors contend that the U.S. and British militaries are operating with principles insufficient to provide the theoretical and conceptual foundation to guide leaders in the current operational environment. Four principles are offered to fill this gap: narrative led operations, discrediting malign behavior, consequence evaluation, and legitimacy. These principles support the goals of maintaining access and influence and, like currently accepted principles, are interrelated.

Narrative Led Operations.

The purpose of narrative led operations is to give coherence to military actions and activities, shape other actors’ conditions and behaviors, and undermine and delegitimize adversaries’ narratives.

The information environment is unforgiving, and competitors are poised to exploit inconsistencies between word and deed. The pervasive nature of the information environment means that actions, from the tactical to the strategic, must be coherent and consistent. The narrative is the “macro intent” or conceptual spine that all operational activity supports. Narratives are constructed upon a thorough understanding of domestic, regional and local audiences; the operational environment; and the desired objectives of the joint, combined force. In competition, the narrative must be consistent with and reinforce the RBIO.

In competition, activities may make sense internally and amongst allies, however, by adopting the principle of narrative led operations this reinforces the stitching together of activities with a coherency that is transparent to both internal and external audiences. Narrative led operations require military leaders to start with “why” and develop a story that gives a spine to their operations. The narrative relies on military activities whose strengths are in its connective tissue with espoused values, follow on actions, and underlying logic. Simply put, actions make the story true. A true, compelling story is more potent than dispassionate logic in human endeavours. The narrative led operations principle of war requires military leaders to understand how activities reinforce or detract from their story with the understanding that sinews of the narrative provide resilience against malign action.

Discrediting Malign Behavior

The purpose of discrediting malign behavior during competition is to enhance friendly access and influence by exposing competitors’ malign activities, thereby undermining their influence, draining their resources, and restricting their physical and cognitive freedom of maneuver.

At present, malign actors exploit the RBIO by using established conventions while simultaneously behaving in subversive ways. These duplicitous efforts present a veiled image of low impact, low risk situations not worthy of armed conflict. Their compound and long-term effects, however, seek to create favourable conditions for the adversary and shape any subsequent conflict. Competitors will continue to exploit this competition space until they assess the cost of their malign behavior is greater than the benefit.

Access and influence are based on mutual benefit and are, therefore, naturally transactional. The combined, joint force seeks to be trustworthy, fair, consistent and, in time of crisis, helpful. In competition, efforts to demonstrate positive action in support of the RBIO indirectly undermines and imposes reputational costs on authoritarian competitors, for example preserving freedom of navigation or supporting a nation following a disaster when adversaries do not. Equally, illuminating and exposing competitor malign behavior that is inconsistent with the RBIO, such as illegal fishing, directly imposes reputational costs. Depending on severity, these costs can be escalated beyond degrading an adversary’s reputation to include economic or diplomatic sanctions. A key role for the military, however, by virtue of its global engagement, is to inform the application of other instruments of national power during competition by observing for and reporting breaches of the RBIO.

As an instrument of national power to achieve political objectives, the military can use the discrediting malign behavior principle of war to expose malign activities and reinforce the benefits of the RBIO. Discrediting malign behavior shrinks the competitors’ influence despite their malicious efforts while reinforcing the value of acting within the RBIO. This principle of war, discrediting malign behavior, guides military leaders in their development of actions to expose or unmask intolerable behavior, seize the initiative when such opportunities present, and contribute to broader Western efforts in competition.

Consequence Evaluation

The purpose of consequence evaluation is to anticipate, mitigate, or exploit the outcomes of military activities by being poised to seize the initiative.

Although there is growing recognition of the Competition Continuum among military and national security leaders, there is little discussion of the consequences of military actions across the continuum. These consequences affect the specific competitors, potentially impact their allies and, if undertaken abroad, could impact the host nation where the competition takes place (e.g., over access to a third nation’s port).

As the joint, combined force acts daily in concert with other instruments of national power to preserve access and influence, the resulting consequences in an ever-changing environment require careful consideration in advance, monitoring in execution, and management following a cycle of assessment. This principle requires military leaders to think about alternative futures during competition, the effects of actions in competition within conflict conditions, and how the sphere of relevant actors may present advantages and disadvantages. Actions across the competition continuum, particularly where discrediting malign behavior is being considered, must continually evaluate and attempt to forecast the potential consequences for all parties to be poised to react and minimize any risk of undermining the core narrative.

Legitimacy.

The purpose of legitimacy is to maintain legal and moral authority in the conduct of operations.

While this principle is already part of U.S. joint doctrine as a principle of joint operations, it is not yet codified in U.K. principles and should be elevated from a mere principle of joint operations to a principle of war. Legitimacy is based on the actual and perceived legality, morality, and rightness of the actions from the various perspectives of interested audiences and has proved to be a critical factor in operations. Audiences include national leadership and domestic population, governments, and civilian populations in the operational environment, as well as nations and global organizations. Without legitimacy, the purpose of the competition and resultant narrative is null.

Conclusion

The U.S. and British militaries have clearly recognized the changing character of war and need to address the broader competition continuum with the publication of new concept documents such as the U.S. JCIC and the U.K. IOpC. However, without a clear articulation of the strategic purpose of competition followed by a more complete examination of the principles necessary to guide these new concepts, military and national security leaders risk stumbling around in the dark finding only what they trip on. Adversaries continue to exploit the West’s artificial cognitive barrier between peace and war. Until they examine the adjustments necessary in their cognitive approach that embraces the Competition Continuum, it will continue to be maneuver space for malign adversaries. Now is the time for the U.S. and British militaries to agree on the strategic “why” and update the principles of war to guide military leaders to maintain competitive advantage across the breadth of the competition continuum.

Thomas Harper is a Colonel in the British Army. An infantry officer from The Rifles Regiment by background, he has served as an Observer/Controller at the Joint Readiness Training Centre, on the staff of SOJTF-OIR and as a Liaison Officer at US Africa Command. He is a distinguished graduate of the AY21 Resident class at the U.S. Army War College.

James Armstrong is a Lieutenant Colonel in the U.S. Army and a distinguished graduate of the AY21 Resident class at the U.S. Army War College.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, the Department of Defense or the U.K. Ministry of Defence.

Photo Credit: Photo by Florian Schmetz on Unsplash

Some potential here but underdeveloped with respect to principles for day to day statecraft in support of national security interests which is what competition is. We survived 70 years of rules based order without principles and I think we can survive without a new set for peacetime

In order to understand such things as “competition” today, one must be able to — first and foremost — explain:

a. Why certain of the U.S./the West’s former “natural allies” during the Old Cold War (for example, certain dictators and authoritarians but also the more-traditional/the more-conservative/the more-no-change [and/or reverse unwanted change] elements of the world’s population –to include these such “conservative” elements here at home in the U.S./the West);

b. Why these such former “natural allies” of the U.S./the West, in many cases, have now become the “natural allies” of our opponents. Example:

“Compounding it all, Russia’s dictator has achieved all of this while creating sympathy in elements of the Right that mirrors the sympathy the Soviet Union achieved in elements of the Left. In other words, Putin is expanding Russian power and influence while mounting a cultural critique that resonates with some American audiences, casting himself as a defender of Christian civilization against Islam and the godless, decadent West.”

(See the “National Review” item entitled: “How Russia Wins” by David French.)

Bottom Line Thought — Based on the Above:

I can only think of one matter which might explain the phenomenon I describe above — this being, that we are now engaged in a New/Reverse Cold War — one in which, accordingly,

a. It is the U.S./the West now (much as it was the Soviets/the communists during the Old Cold War) who is currently seen as the “threatening” entity — that is, the entity seeking to achieve “revolutionary” political, economic, social and/or value change both at home and abroad — and

b. It is our opponents now (much as it was the U.S./the West back during the Old Cold War) who are now seen as the “savior” entity — that is, the entities standing against all these such unwanted political, economic, social and/or value changes.

In our article above regarding “competition,” the concept of “narrative-led operations” is said to play an exceptionally important role:

“The purpose of narrative led operations is to give coherence to military actions and activities, shape other actors’ conditions and behaviors, and undermine and delegitimize adversaries’ narratives.

The information environment is unforgiving, and competitors are poised to exploit inconsistencies between word and deed. The pervasive nature of the information environment means that actions, from the tactical to the strategic, must be coherent and consistent. The narrative is the “macro intent” or conceptual spine that all operational activity supports. Narratives are constructed upon a thorough understanding of domestic, regional and local audiences; the operational environment; and the desired objectives of the joint, combined force. In competition, the narrative must be consistent with and reinforce the RBIO.

In competition, activities may make sense internally and amongst allies, however, by adopting the principle of narrative led operations this reinforces the stitching together of activities with a coherency that is transparent to both internal and external audiences. Narrative led operations require military leaders to start with ‘why’ and develop a story that gives a spine to their operations. The narrative relies on military activities whose strengths are in its connective tissue with espoused values, follow on actions, and underlying logic. Simply put, actions make the story true. A true, compelling story is more potent than dispassionate logic in human endeavours. The narrative led operations principle of war requires military leaders to understand how activities reinforce or detract from their story with the understanding that sinews of the narrative provide resilience against malign action.”

This being the case, then:

a. If the U.S./the West’s (both at home and abroad) political objective is “revolutionary” in nature (think: designed to achieve — both here at home and there abroad — the political, economic, social and/or value changes needed by such things as capitalism, globalization and the global economy — such, indeed, being consistent with upholding the RBIO — both yesterday and today?)

b. Then what “narrative” should we use; this to:

1. Effectively facilitate our such “revolutionary” political, economic, social and/or value “change” initiatives and

2. Effectively thwart/stand against our opponents’ (those both here at home and there abroad) efforts to prevent us from achieving our such “revolutionary”/”change” goals?

(In this latter regard, to especially note our opponents “containment” strategy in the New/Reverse Cold War of today; wherein — much like in our “containment” strategy against the “revolutionary” Soviets/the communists in the Old Cold War of yesterday — these such “containment” entities today make significant use of (a) the conservative elements of the world’s populations and (b) especially these such elements in the proponent “revolutionary” countries themselves.)