Self-awareness continues to be a requirement for effective leadership at every level

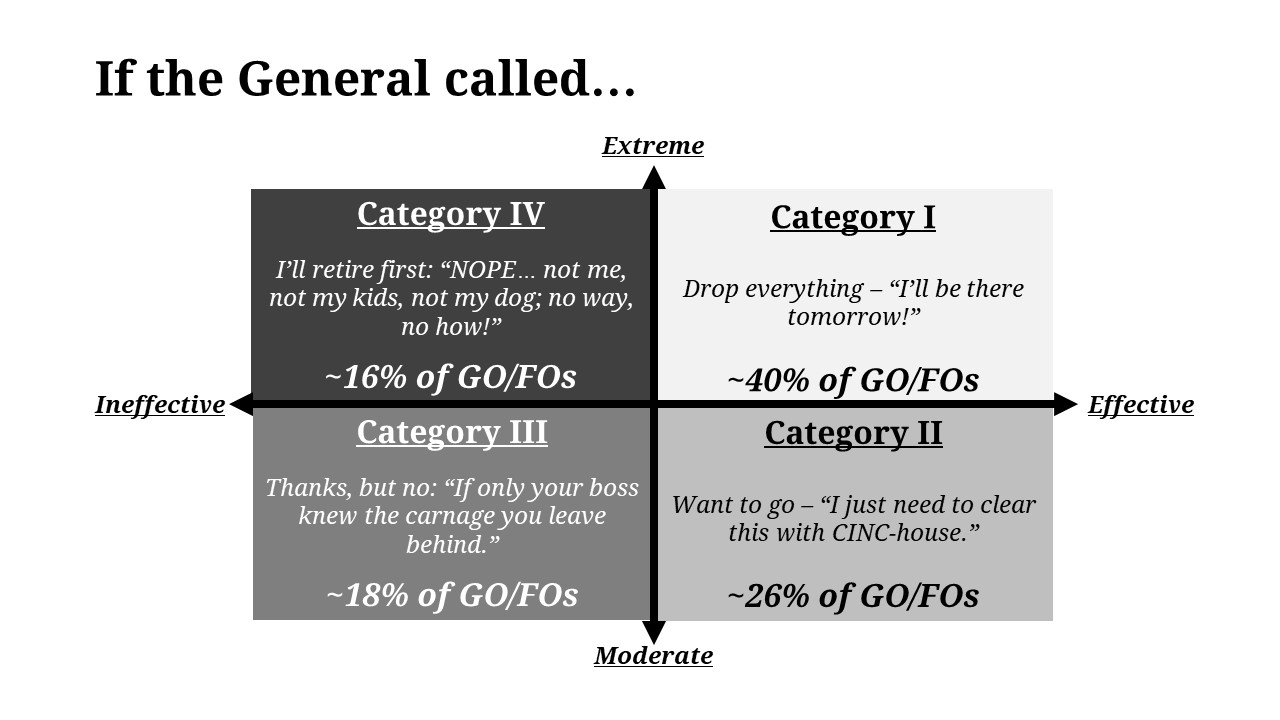

For over a decade, several Army War College (USAWC) colleagues have run a simple exercise with their students. Students are asked to think of the general officers and flag officers (GO/FO) with whom they have directly worked or have only one degree of separation – GO/FOs with which each student is very familiar. Based on receiving a notional phone call offering an assignment with that GO/FO, students then place each senior leader into one of four mutually exclusive buckets aligned with four responses.

- “I will be there tomorrow if you need me.” Any assignment with this individual will be personally and professionally exceptional.

- “I would like to. Let me talk to my family and see what we can work out.” The GO is good, but there are caveats.

- “Thanks, but no. If only your boss knew how you got things done and the carnage you leave behind.” There are some significant shortcomings in this officer that could make my life miserable.

- “Hell No! Not me nor anyone I care about should be subject to such leadership!” This individual should not be in positions of senior leadership. Toxic. Dysfunctional.

Students have little trouble placing their senior leaders in the described categories. Over the last decade, those results demonstrate a consistent pattern, as the Figure here shows.

The reactions among Senior Service College (“War College”) students seeing this chart are mixed. Some are content with about two of five leaders generating unquestioning support. Others are dismayed that the same system which developed Category I leaders also allows Category IV officers to make general officer.

Discussions about the extremes – Category I and IV GO/FOs – often move directly to conceptual and interpersonal domains. Students describe the best GO/FOs as being simply smarter than others and bringing sophisticated perspectives to daily interactions. They demand high levels of performance, of course, but also demonstrate genuine care for individuals. They make all ranks feel valued. They pay attention to the nuances of organizational climate. Officers in Categories III and IV are described as tending to substitute activity for brains (Hooah!) and inappropriately oversimplify complex situations. They are either unwilling or unable to get above a problem to see it in time and space, and are simplistic in their perspective.

Such limitations may be forgiven, but the Category IV leaders are also simply jerks. They are described as patronizing, arrogant, and only interested in their own short-term success rather than the longer-term success of the profession, their units, and their people.

War College students know and have experienced the difference; they are not rookies who need coddling. These are centrally selected, uniquely successful Lieutenant Colonel-level (O-5) commanders who themselves have made hard decisions in peace and war. They know the difference between high standards, tough love, and an unreasonable ass. They have earned a vote in discerning good from bad senior leadership.

The consistent distribution of GO/FO categorization by these experienced and successful officers should cause concern and solicit action by the Army. Our intent is not to simply cast stones at senior leaders – many of whom are models of the profession – but to recommend raising the floor for selection to this influential group. We begin by offering two caveats.

First, GO/FO development begins well before selection to flag rank. Considerable winnowing of the officer pool begins at selection for Lieutenant Colonel-level Command, then even more for Colonel-level Command. Second, we recognize the recent developmental efforts instituted and resourced by Generals Odierno and Milley for the Army. For example, the Army Senior Education Program (ASEP) includes specialized courses for high potential colonels as well as for 1, 2, and 3-star generals. We suggest, however, that these courses are not enough.

We recommend three sets of actions to address the challenges facing the Army: focus on enhancing the cognitive requirements of the entire officer corps; adjust systems to identify and eliminate Category III and IV GO/FOs; and enhance the already effective GO/FO leaders in Categories I and II. We want to make the good even better.

Action 1: Screen for cognitive preparedness

The Army needs a serious discussion of cognitive requirements within its officer corps. Cognitive research suggests that general intelligence is a function of genes and early childhood experiences – neither of which are highly malleable in the population of military officers. Consequently, Army selection processes should insure at least moderate cognitive capacity necessary to operate effectively at all levels.

The Army should better screen officer candidates before commissioning to insure that future general officers have the requisite cognitive skills. Accordingly, the Army needs a bridging strategy between a decision to require all Army officers to complete a pre-commissioning ASVAB and their selection for War College attendance some 20 years later. An option is to administer the Graduate Record Exam and consider its results in War College selection.

Additionally, developmental programs can enhance cognitive skills of senior leaders. Some have suggested at the senior level, openness – a personality trait that embraces complexity, intellectual debate, and curiosity – might be the most important aspect for strategic-level effectiveness. Openness can be reliably measured and used in developmental assessments for high-potential officers. Such assessments follow the assumption that awareness of personality characteristics (and associated impact on effectiveness) serves as motivation to align behavior with performance requirements. In the end, coaches can use developmental assessments to facilitate good senior leaders being even better.

Action 2: Enhancing existing selection processes to weed out Category III and IV officers

Our assertion is that the Army should not expend the institutional energy to rehabilitate senior officers in Categories III and IV. Those officers have spent 20+ years in a structured, comprehensive developmental system. There is but one institutional solution for these officers: “select them out” – and centralized board processes are the only systemic way to do this.

Poor leaders … often continue to be promoted because they are very good at impression management

Army conventional wisdom regarding Brigadier Generals suggests that selection of the next group of 30 colonels – those just under the cut line – would not adversely impact Army missions and task performance. It follows that more comprehensive comparisons can be made for these top performers; accordingly, more data should be considered in selection processes. As a performance-based organization, the Army Officer Evaluation Reports should continue as the primary means to identify top performers. However, selection boards should consider not only what is achieved, but also how performance outcomes are attained.

The Army has tinkered with developmental 360-degree assessments through the Multi-Source Assessment and Feedback (MSAF) program. Importantly, 360-degree assessments include subordinate, peer, and superior behavioral measures that identify areas of relative strength and weakness. While officer requirements for initiation of an MSAF have been recently rescinded, self-awareness continues to be a requirement for effective leadership at every level. Recent changes do not invalidate the concept but suggest the Army’s policy and implementation processes require adaption. Accordingly, one option for more comprehensive data is to develop and implement evaluation data from subordinates or peers in selection processes at the senior level.

Leadership research suggests a critical caveat here. The same system and processes used for developmental feedback should not be used for evaluation. For example, while a developmental system might allow the officer to select the raters and have private access to their results, our proposed evaluative system would choose the raters and the results would be available to all members of an Army Brigadier General selection board. Human Resource Command could identify the battalion commanders – and potentially also command sergeants major – rated or senior rated by that individual while in brigade or other O-6 level command. Randomly selected subordinates would be required to complete a brief evaluation (e.g., “Would you choose to work for this officer again?” “Is this officer a role model of what an Army General Officer should be?”), characterized as a personal responsibility to the military profession.

A second option to expand the data available to boards would be peer assessments, following a process similar to the one described above. An often-used critique of a peer-based option is that some officers might use such a process to undercut a competitor, making themselves look better by undermining colleagues. We can control for such critiques by also including one’s ratings of others as part of one’s file. Individuals who are overly harsh on all others might actually be highlighting their own insecurities, thereby identifying themselves for non-selection.

Poor leaders – those represented by the Category III and IV generals – often continue to be promoted because they are very good at impression management. They hide problematic tendencies from their superiors. Making information from subordinates and peers available to decision makers through the inclusion of additional performance data – capturing both what is accomplished as well as how it is accomplished – is necessary to identify those senior officers. Of course, one could argue that more comprehensive systems be implemented earlier in an officer’s career. But to change the culture of the Army, expanding the data used for selection must start with its most senior leaders.

Action 3: Enhance the performance of officers in Categories I and II

The Army must invest in enhancing the performance of leaders assessed in the two higher-performing categories. Such a focus on enhancing strengths is consistent with proven approaches to leader development. Because we discussed cognitive screening in Action 1, this discussion of enhancing the performance of both Category I and II officers will focus on the interpersonal domain. And, while we suggested earlier that Category III and IV generals are beyond development, enhanced actions discussed here might have the related benefit of developing those officers – over time – to higher levels of effectiveness, too. Specifically, we will suggest that such enhancements occur through increased reflection and awareness, coupled with an enhanced appreciation for and development in the unique responsibilities of strategic leaders.

Developing interpersonal skills can be accomplished through multiple means. One opportunity demands reflection of previous leadership behavior. This reflection considers previous events and ponders alternative behaviors or perspectives – both self and others – that might have improved outcomes, either in content, processes, or commitment. Upon reflection, many senior leaders understand previous challenges in a more comprehensive way. While the benefits require an openness to learning and time to complete, the results are a more sophisticated understanding of both direct and indirect effects, number and perspectives of stakeholders, and symbolic considerations that might have been minimized earlier. Taking such a comprehensive view, fundamentally, enhances their wisdom when faced with new challenges.

A second opportunity for interpersonal development is exposure to the multiple theories of human behavior. Advances in behavioral science have resulted in theories of interpersonal and organizational effectiveness that are both nuanced in application and scientifically supported in content. Development, then, occurs through exposure to those multiple theories, and probably more importantly, the integration of those theories into a personal theory of leadership that continues to expand and adjust individual perspectives in nuanced ways to deal with the expanded stakeholders of the strategic environment.

Finally, coaches can provide a valuable service to those leaders who wish to improve. Value, though, is not in the war stories of coaches having faced similar challenges (one could argue that no two strategic challenges are the same), but in the questions asked to help leaders refine understanding of their own experiences.

Conclusion

The significant impact of Army General Officers across the force, combined with a long-term assessment of their effectiveness by seasoned and successful subordinates, suggests the need for enhanced senior leader selection and development processes. While one might mistakenly interpret our intent as individually focused, the overall purpose of our argument is to enhance the institution of the U.S. Army. As the profession is more important than the individuals in it, the stewards of that profession must ensure that it is always improving. And enhancing effectiveness, though complex, begins with oneself. Consequently, we close this paper with the question posed to our USAWC students at the end of the initial thought exercise: “In which category would your folks place your name?”

Charles Allen is Professor of Leadership and Cultural Studies at the U.S. Army War College. Craig Bullis is Professor of Management at the U.S. Army War College. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

Photo: Trier, Germany circa 1919. Officers of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) receiving medals from General John J. Pershing, Commanding General of the AEF.

Photo Credit: U.S. Army photo via Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Seems like there is a major component missing: generals that might actually perform well in wartime.

Those who do well are loved by their troops because they are right there, not several of layers of helicopters above them or linked in by video.

Far too many generals can’t cut it (in Vietnam they stayed in their air-conditioned trailers or hooches), but they waited out their year, collected their medal or two and moved on to a better assignment.

The time of the Pattons and Hollingsworths are long-since past, it seems, in deference to writing good reports and being nice to others, etc.

As someone who has worked on every staff level there is, I can tell you that there are people who will want to work for most of the GO/FO type that exist because they (the subordinates) know how to work the GO/FO to get what they want. Secondly, some of the nastier senior leaders will fail in the 21st century due to the current culture, BUT they would be utterly priceless if the US ever had to fight for it’s life. Lastly, leadership is always about trust – so the question to be answered is: “would I go to war with him?” IMO that is the ultimate question to apply to judging any officer.

Great questions and insights. We may want to study the UK Army to see how CAT 1 GOFOs can be made. https://fromthegreennotebook.com/2019/03/07/sir-solitude-leadership-lessons-from-lieutenant-general-sir-graeme-lamb/

Part of a leader’s performance is basic brains and skill–smarter officers with better leadership education will perform leadership tasks more effectively and efficiently–so we should ensure that our generals and admirals have mastered the academic skill of leadership. This is an absolute metric, so it is fairly simple to select for, although it will require moral courage in the hopefully rare case of an officer with a strong operational record being retired over poor performance at war college.

The other part of a leader’s performance is their mindset and mental timeline, which is much more situational in desirability. A leader driven to achieve immediate results is valuable as a wartime operational commander, but peacetime garrisons and training commands are better served by leaders with longer views. If we must select a single model for a mixed career, we need all leaders to leave their successors a command at least as strong as what they were given.

What Craig and Chuck are proposing is an institutionalized and bureaucratic system to solve a perceived problem.

I will assume for a moment that we have established that there are several boundaries across which no GO or FO (or any American Officer or NCO) will be permitted (lying, cowardice, infidelity to the oath of office, being on the take, sexual belligerence, etc.)

That said, there is not a single culture in an Army/Air Force/Space Force/Naval force structure, therefore, there is not a single leadership style that will succeed with all cultures at all times. Witness the successful Marshall (and Ike) approach whereby Division CGs in WWII were moved around willy nilly without harm to fit the “culture” of a particular fighting front, Corps, or Division. Or a narcissistic AH like GA MacArthur being an indispensable heroic leader in the Pacific in WWII and fired in Korea for being the same narcissistic AH.

We should, IN ALL SERVICES, ask the article’s four questions slightly differently. E.g, General XXX calls and says to you: George I am being assigned to command the YYY Division, Air Force, Flotilla and it’s now scheduled for a year’s potentially combat deployment to northern Iraq and Eastern Syria. I need you to be one of my Battalion Commanders or my G3 (or A4, N5) and get them ready for combat. Will you?

Another way to ask is to offer a lousy assignment (kinda). George, I am being assigned as the IG for the NATO forces in Ukraine. I want you to be my Deputy for Azerbaijan with only one staff guy stationed alone in Baku. Will you? (Yes, I know that is not part of NATO and only kinda near Ukraine, but it is the lowest national capital in the world). (Physically, Azeris, physically.)

I fully understand that some modicum of IQ is important, but that can be screened during accession. EQ is probably a better measure for leadership propensities, but that must also be applied to the mission and culture, not to a specific mark on the wall. In my experience, there are some seemingly magic folks who have maybe a 110 IQ but can “see” patterns and calculate combat outcomes where a 150 IQ might only be able to “see” the quantum mechanics of approaching spacecraft and have no clue who the two-legged human critters are operating them.

We need both, depending on the when, where, mission, and culture (both unit and battlefield.)

There are several folks whom I would follow into the fires of hell. But they could not be AHs to save their souls, hence could not serve to get a slothful unit combat ready in minimum time. And yes, sometimes that is exactly what it takes. Sometimes not.

Deryl McCarty, Colonel, USAF (Ret)