Churchill, an avid painter, ‘saw the beauty and vitality of details, and their effect on larger strategic issues, and demanded that they be scrutinized all the time.’

You have likely come across a quote, article, or visual media reference to Winston Churchill in the past couple of years. The British statesman is one of the most quoted authors by American lawmakers, perhaps because you can find a Churchill quote to fit nearly any occasion. Gary Oldman’s Oscar winning portrayal of Churchill in the 2017 movie “Darkest Hour” further exposed a new generation to the contributions of this statesman.

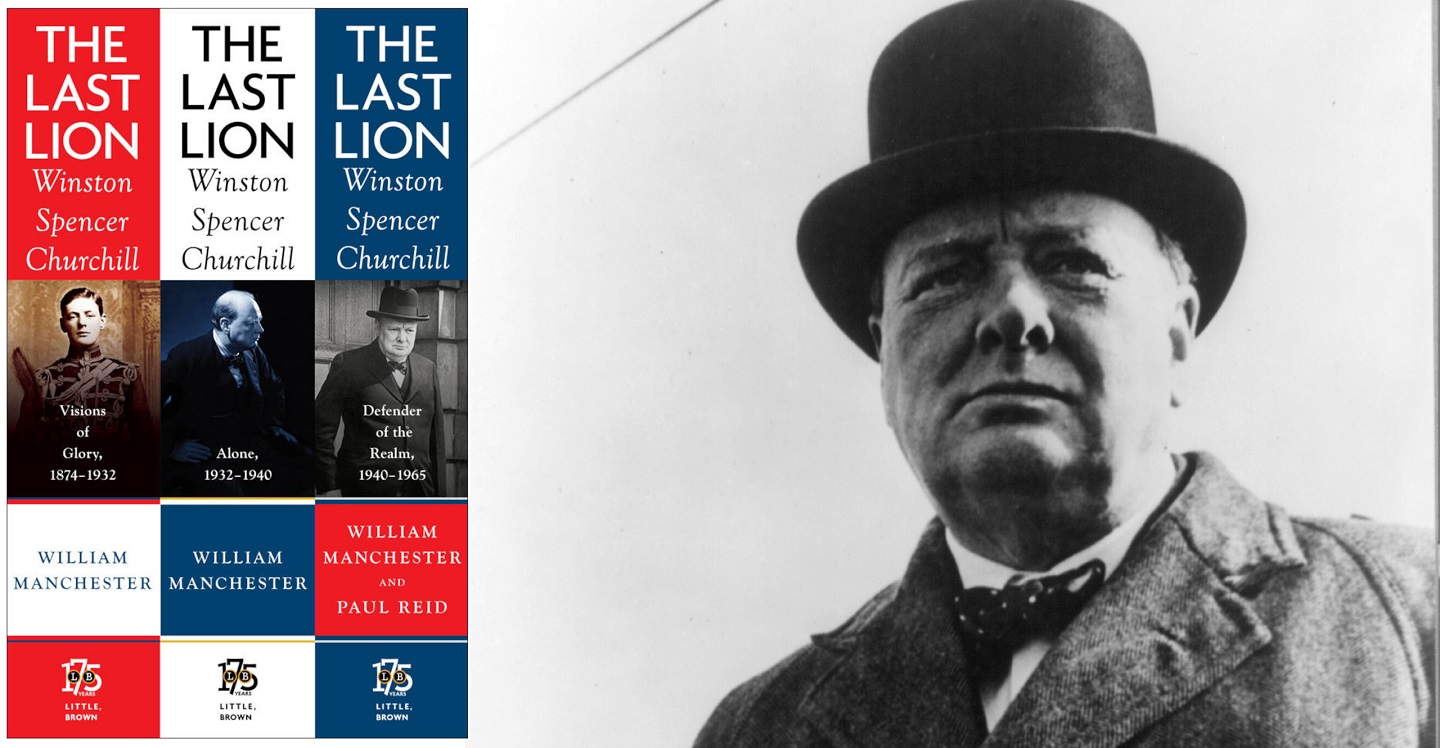

This recent attention to Churchill’s historical contributions prompted me to read the The Last Lion series by William Manchester and Paul Reid. This is no small task as the three volumes total a little over 3,000 pages. On the far side of these pages, however, are some valuable lessons for understanding the 20th century’s great wars and insights on preparing for the next one.

Although the lessons from these volumes are many, Manchester and Reid use examples throughout Churchill’s lifetime of service that point to three particularly impactful facets of his leadership: his lifetime of study and diverse experiences that prepared him for wartime leadership, his ability to anticipate future conflict, and his recognition and development of subordinates. There are dozens of Churchill biographies to choose from. What separates The Last Lion is Manchester’s passion for details, a quality that the subject of his biography shared as well. Churchill, an avid painter, “saw the beauty and vitality of details, and their effect on larger strategic issues, and demanded that they be scrutinized all the time.” Manchester’s focus on such details during Churchill’s journey from a lonely childhood to leader of Great Britain during their finest hour paints a full picture for the reader of one of history’s greatest statesmen.

First, The Last Lion provides valuable lessons for preparing strategic leaders. Churchill provides a model of developing strategic acumen through combining experiences as a junior officer with a lifetime of intensive self-study. Manchester notes that Churchill was a rather unremarkable student in school, but starting as a young boy he displayed a penchant for reading and creativity. It took him three tries to gain admission to Sandhurst, but he was eventually commissioned as an infantry officer and saw action in Cuba, India, Sudan, and South Africa. Drawing on his experiences as a young officer and his self-study, Churchill published books on military subjects and combined these qualities to prepare for service as the First Lord of the Admiralty (akin to our Secretary of the Navy) among other positions.

A key insight from Churchill’s career is that strategic leaders are constantly preparing and reassessing, and these leaders will undoubtedly have missteps along the way. In 1932, Churchill found himself in a personal and professional wilderness: he lost all his money in the stock market crash, no longer held a political position, and was even hit by a car in New York City. One could imagine Churchill, at this point in his life, wondering if he would ever return to a position of power.

Manchester’s description of Churchill’s conviction and preparation in his times of struggle help the reader understand how he rallied the British public in their time of crisis. When Churchill told the House of Commons in the dark days of the fall of 1940 that “many more misfortunes, many shortcomings, many mistakes, many disappointments will surely be our lot,” he drew on his experiences from World War I and his own wilderness journey to steel lawmakers and the public for the tough road ahead. Churchill had a lifetime of experiences and self-study to fall back on, and it was his relentless pursuit of self-preparation that equipped him for his service as Prime Minister when his country needed him the most.

Second, The Last Lion provides insights into Churchill’s ability to anticipate future conflict. Strategists must put themselves in the mind of their adversary, and to do this effectively, they must have knowledge of this adversary. As others sought peace with Germany, Churchill saw that Hitler drew on Germany’s weakness and pride to fuel his power. As Manchester notes in Volume 2, “political genius lies in seeing over the horizon, anticipating a future invisible to others.” Churchill was out of public office during the lead up to World War II, but he leveraged relationships with leaders in government to stay apprised of events.

His foresight that appeasement was the wrong track to take with the Germans led in part to his selection as Prime Minister. Manchester also traces Churchill’s assessment of Stalin as a tacit ally and eventual foe.

Manchester paints the details of this critical time in such detail for the reader that you can clearly picture Churchill, a legendary night owl, huddled over his desk with newspapers and speeches piecing together his assessment of Hitler’s intentions. His foresight that appeasement was the wrong track to take with the Germans led in part to his selection as Prime Minister. Manchester also traces Churchill’s assessment of Stalin as a tacit ally and eventual foe. As America faced Japan and the exhausted British Army emerged from years of fighting, Churchill championed the integration of Germany into the European nations to confront this rising threat.

Finally, the The Last Lion series underscores the leader’s role in maximizing the contributions of their subordinates. Great leaders are able to draw upon the knowledge and skills of their subordinates at the right time and place. Churchill excelled at this skill as evidenced by his penchant for details and desire for debate.

An example early in World War II is Churchill’s assessment of the German use of radio beams to guide their aircraft. Although many experts doubted the Germans had this capability, Churchill asked a 28-year-old scientist to brief him on it. Manchester and Reid stress that Churchill “came at every issue with a painter’s eye,” recognizing that small details can have a large effect on the overall picture and should be scrutinized accordingly. Drawing on the insights of this young scientist, the British devised a way to jam these beams and disintegrate a major capability of the Germans. The lesson from this episode is that Churchill recognized experts can be blinded by intelligence that goes in the face of their prior beliefs.

Manchester and Reid provide some examples of consequences when leaders fail to draw upon the insights of their subordinates to challenge prior beliefs. Prior to the German invasion of France in World War II, the French command did not believe an attack through the Ardennes was feasible. French pilots reported tanks and trucks headed for the Ardennes, but French military leaders viewed these reports as not credible. German operations orders captured by French intelligence that detailed the Ardennes invasion were dismissed as a plant. Similarly, Stalin ignored warnings of Operation Barbarossa, the German Invasion of the Soviet Union, from his best spy in Tokyo and a captured German deserter because of his prior beliefs about Hitler’s probable actions.

The Last Lion series thus underscores the importance of a climate in which leaders are willing to receive information that is counter to their established beliefs. Leaders must also be willing to receive bad news. German forces were afraid to report the British success against the Luftwaffe early in the war which led to poor planning assumptions. Since German forces estimated that 1,800 British fighters were shot down instead of the actual number of 500, Hitler turned to bombing British cities instead of focusing on the Royal Air Force. As Churchill put it, “three or four times in these months the enemy abandoned a method of attack which was causing us severe stress, and turned to something new.” To maximize the potential of our subordinates, leaders must value openness and create an environment where subordinates can communicate bad news.

Arguably more than any other leader during the interwar period, Winston Churchill understood that a statesman must always prepare for war. As Manchester writes in Volume 1 of the series, “they [other lawmakers] hold that peace is the norm and war a primitive aberration…Churchill held otherwise.” Churchill would endorse the Army’s premise that competition and conflict, not war and peace, characterize the operational environment of the 21st century. The Last Lion volumes capture his lifetime of lessons that can aid our leadership in competition and conflict. Although he was a voracious reader, Churchill would recognize that a commitment to reading the over 3,000 pages of The Last Lion volumes would be a challenge for many of us. However, he would also consult his notes and use this quote to encourage you to undertake this task: “The longer you can look back, the farther you can look forward.”

LTC G. Lee Robinson, PhD, is a U.S. Army Aviation Officer and the Commander of the 603D Aviation Support Battalion stationed at Hunter Army Airfield, Georgia. A 2000 West Point graduate, he is an Advanced Strategic Planning and Policy Program Goodpaster Fellow and holds a PhD in Public Administration from the University of Georgia. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress (via Wikimedia Commons)

Other releases in the “Dusty Shelves” series:

- KOREA ON THE BRINK: GENERAL JOHN WICKHAM AND POLITICO-MILITARY CRISIS MANAGEMENT

(DUSTY SHELVES) - FIGHTING BY MINUTES, THIRTY YEARS LATER

(DUSTY SHELVES) - THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER (1988): THE FORGOTTEN PRIMER ON LEADERSHIP

(DUSTY SHELVES) - RIDGWAY’S KOREAN WAR

(DUSTY SHELVES) - ALL WAR IS LOCAL: ANTHONY QUAYLE’S EIGHT HOURS FROM ENGLAND

- POST-WAR TRUTH TELLING: THE WAR MANAGERS

- DYE: EXALTING THE TAIL OF THE AIRPOWER TOOTH

(DUSTY SHELVES) - PEACE FORMS: LOOKING BACK TO THE FUTURE OF WAR AND ANTI-WAR

- SHERMAN: THE OUTLIER OF INTERWAR “ATLANTIC” AIR THEORY?

(DUSTY SHELVES) - STRUGGLING TO SEE THE FUTURE: UNLESS PEACE COMES

(DUSTY SHELVES)