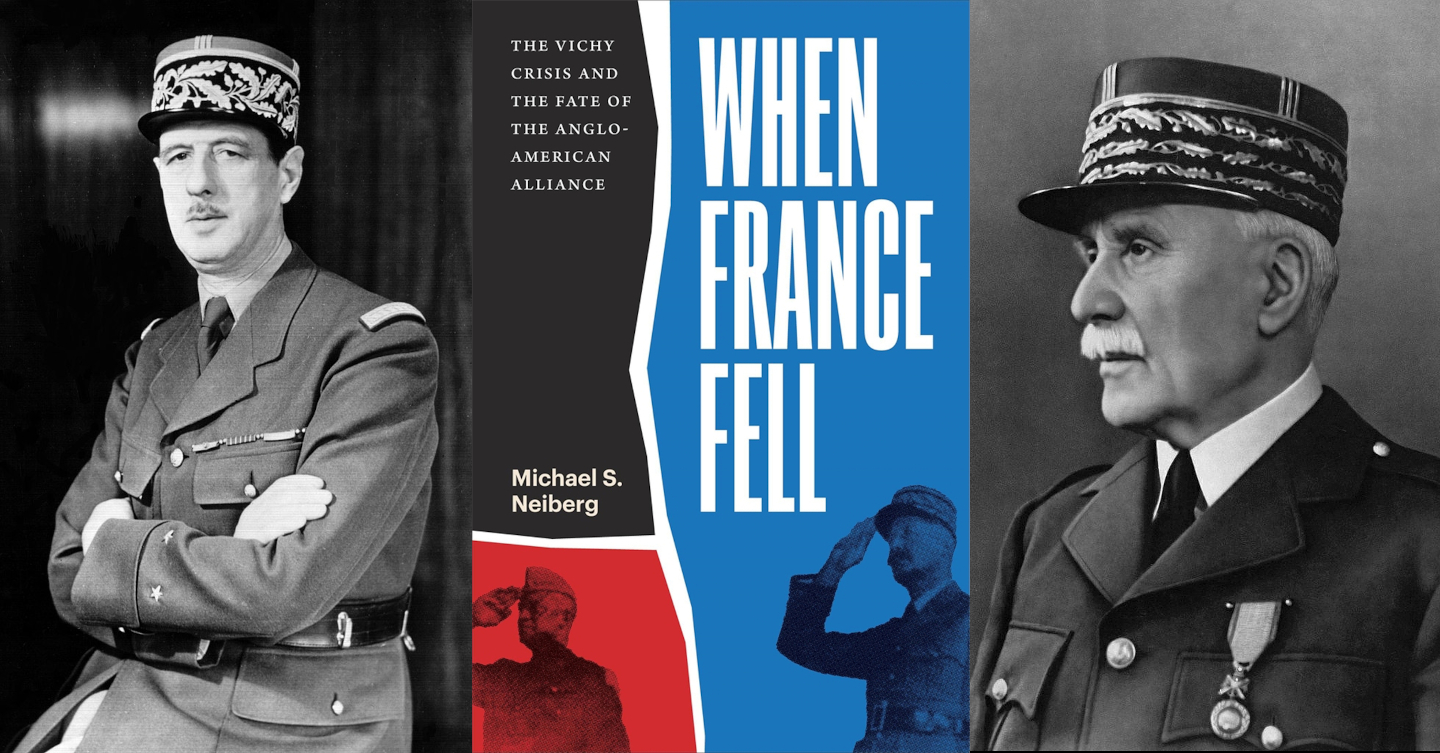

Usually Michael Neiberg is the interviewer in our On Writing series. In this episode he sits down with podcast editor Ron Granieri as the interviewee. They’re talking about his new book When France Fell: The Vichy Crisis and the Fate of the Anglo-American Alliance. The two examine the conflict between Free and Vichy France and the interaction with the Allies in the early days and throughout World War II. They discuss relationships rife with bad assumptions, mistrust, failed promises and difficult personalities which leads to a much better understanding of the United States’ dealings with its oldest ally.

I had always been fascinated by Vichy. It’s this strange political animal that really has no precedent to it. Nothing like it has ever come before or since where half the country is occupied the other half is left independent ,technically neutral and in control of the French empire and in control of the French fleet.

Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | Podchaser | Podcast Index | TuneIn | Deezer | Youtube Music | RSS | Subscribe to A Better Peace: The War Room Podcast

Michael Neiberg is the Chair of War Studies at the U.S. Army War College.

Ron Granieri is Professor of History at the U.S. Army War College and the Editor of A BETTER PEACE.

The views expressed in this presentation are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

Photo Description: (L) General Charles de Gaulle leader of Free France 18 June 1940 – 3 June 1944 (R) Marshal Philippe Pétain leader of Vichy France 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944.

Photo Credit: Portraits courtesy of Wikimedia Commons (L) Office of War Information, Overseas Picture Division (R) Creator unknown

Other releases in the “On Writing” series:

- COLONELS WRITING FOR COLONELS (RE-RELEASE)

- ON WRITING: MILITARY AUTHORS AND THE HARDING PROJECT (RE-RELEASE)

- FIGHTING TOGETHER: THE CANADIAN-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP IN WORLD WAR II

(ON WRITING) - THE SCHOLAR AND THE STRATEGIST:

SIR HEW STRACHAN

(ON WRITING) - COLONELS WRITING FOR COLONELS

- ON WRITING: MILITARY AUTHORS AND THE HARDING PROJECT

- UNDERSTANDING RUSSIAN CULTURE: JADE McGLYNN

(ON WRITING) - CHINA’S SHIFTING HISTORY: STEPHEN PLATT

(ON WRITING) - UNDERSTANDING CHINA THROUGH ITS RECRAFTED PAST: RANA MITTER

(ON WRITING) - WRITING ON A DEADLINE: SHASHANK JOSHI

(ON WRITING)

Questions — relating to a potential comparison/a potential similarity between (a) the U.S. today and (b) France before World War II:

1. Should we consider the divide in the United States today between:

a. Our more-modern, our more-democratic, our less-racist, our less-religious, our less-nationalist, etc., elements and

b. Our more-traditional, our more-authoritarian, our more-racists, our more-religious, our more-nationalist, etc., elements

Should we consider that this divide might mirror the divide between similar elements within France before World War II? Likewise, and as to this exact such divide:

2. Should we consider that our more-traditional, etc., elements (see my item “b” above) today appear to view Russia; this, in much the same “natural ally” way that France’s more-traditional, etc., elements might have viewed Nazi Germany before and during World War II? As to this such question, here are some examples re: how more-traditional, etc., Americans appear to view Russia today:

“Liberal democratic societies have, in the past few decades, undergone a series of revolutionary changes in their social and political life, which are not to the taste of all their citizens. For many of those, who might be called social conservatives, Russia has become a more agreeable society, at least in principle, than those they live in. Communist Westerners used to speak of the Soviet Union as the pioneer society of a brighter future for all. Now, the rightwing nationalists of Europe and North America admire Russia and its leader for cleaving to the past.”

(See “The American Interest” article “The Reality of Russian Soft Power” by John Lloyd and Daria Litinova.)

“Liberal democratic societies have, in the past few decades, undergone a series of revolutionary changes in their social and political life, which are not to the taste of all their citizens. For many of those, who might be called social conservatives, Russia has become a more agreeable society, at least in principle, than those they live in. Communist Westerners used to speak of the Soviet Union as the pioneer society of a brighter future for all. Now, the rightwing nationalists of Europe and North America admire Russia and its leader for cleaving to the past.”

(See the National Review” article: “How Russia Wins” by David French)

Note that the below comment corrects the above comment, as the above comment does not show the proper quote from the National Review article “How Russia Wins” by David French.

Apologies for this mistake.

Questions — relating to a potential comparison/a potential similarity between (a) the U.S. today and (b) France before World War II:

1. Should we consider the divide in the United States today between:

a. Our more-modern, our more-democratic, our less-racist, our less-religious, our less-nationalist, etc., elements and

b. Our more-traditional, our more-authoritarian, our more-racists, our more-religious, our more-nationalist, etc., elements

Should we consider that this divide might mirror the divide between similar elements within France before World War II? Likewise, and as to this exact such divide:

2. Should we consider that our more-traditional, etc., elements (see my item “b” above) today appear to view Russia; this, in much the same “natural ally” way that France’s more-traditional, etc., elements might have viewed Nazi Germany before and during World War II? As to this such question, here are some examples re: how more-traditional, etc., Americans appear to view Russia today:

“Liberal democratic societies have, in the past few decades, undergone a series of revolutionary changes in their social and political life, which are not to the taste of all their citizens. For many of those, who might be called social conservatives, Russia has become a more agreeable society, at least in principle, than those they live in. Communist Westerners used to speak of the Soviet Union as the pioneer society of a brighter future for all. Now, the rightwing nationalists of Europe and North America admire Russia and its leader for cleaving to the past.”

(See “The American Interest” article “The Reality of Russian Soft Power” by John Lloyd and Daria Litinova.)

“Compounding it all, Russia’s dictator has achieved all of this while creating sympathy in elements of the Right that mirrors the sympathy the Soviet Union achieved in elements of the Left. In other words, Putin is expanding Russian power and influence while mounting a cultural critique that resonates with some American audiences, casting himself as a defender of Christian civilization against Islam and the godless, decadent West.”

(See the National Review” article: “How Russia Wins” by David French)