One way to look at COVID-19 is as a conflict situation, involving a series of victims, rescuers, and persecutors/perpetrators.

Globally, COVID-19 produced a triple crisis in healthcare, the economy, and politics. COVID-19 has infected nearly 45 million people, resulting in over 1 million deaths. The World Bank estimated that the global economy will contract by 5.2 percent, which will lead to the worst recession since World War II. The mishandling of COVID-19 raised significant domestic and international tensions.

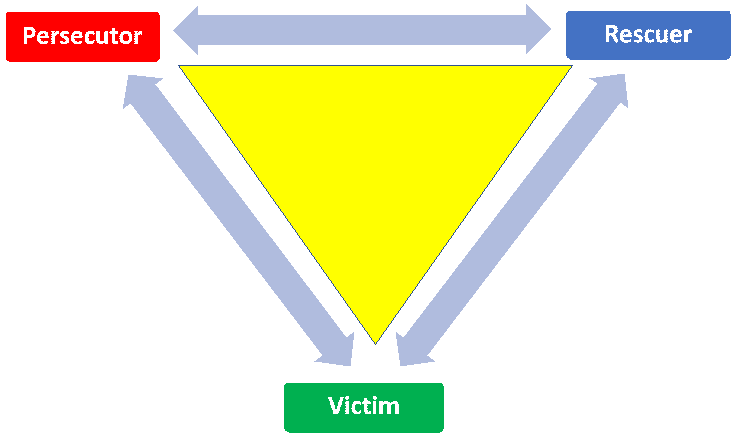

Given the severity of the triple crisis and the high-stakes involved, it is in the interest of states to avoid blame. Hence, the COVID-19 environment is ripe for disinformation, and in this environment, China has been besting the United States in crafting a narrative to suit its purposes. One way to look at COVID-19 is as a conflict situation, involving a series of victims, rescuers, and persecutors/perpetrators. Defining “who’s who” in this dramatic tale is critical to controlling and influencing the information environment, and using Karpman’s “drama triangle” as an analytical tool enables us to unpack the COVID-19 conflict and the dynamic roles associated with it.

Karpman’s Drama Triangle

In the late 1960s, a young postgraduate student named Stephen Karpman developed a theory about conflict. He argued that every conflict is characterized by a triangular relationship involving a victim, rescuer, and persecutor/perpetrator. Karpman was interested in acting and was even a member of the Screen Actors Guild. He consciously chose to refer to the drama triangle rather than conflict triangle as each role is casted or played by an actor.

The victim says “poor me” and feels oppressed; the rescuer’s line is typically “let me help you” and sometimes acts as an enabler; and the persecutor/perpetrator plays the villain, an oppressive and authoritarian figure. But here is the most important feature of Karpman’s drama triangle: the relationship between the victim, rescuer, and persecutor/perpetrator is constantly in flux, and the same actor can play multiple roles. Which actors are in which roles depends on perspective, time, and who is telling the story. To underscore his point, Karpman made reference to the children’s fable of the Pied Piper of Hamelin;

In the Pied Piper, the hero begins as Rescuer of the city and Persecutor of the rats, then becomes Victim to the Persecutor mayor’s double-cross (fee withheld), and in revenge switches to the Persecutor of the city’s children. The mayor switches from Victim (of rats), to Rescuer (hiring the Pied Piper), to Persecutor (double-cross), to Victim (his children dead). The children switch from Persecuted Victims (rats) to Rescued Victims, to Victims Persecuted by their Rescuer (increased contrast).

Karpman’s drama triangle has since become famous (at least in the field of Psychology) and helps to shed light on disinformation surrounding COVID-19.

COVID-19: The Origins

At first, COVID-19 spawned a dramatic situation that cast Karpman’s three actors: Chinese citizens in Wuhan were victims of COVID-19 while the Chinese government stepped in as rescuer. The World Health Organization (WHO) even commended China for its “commitment to transparency.” Meanwhile, some experts pointed to a bat as the perpetrator for passing COVID-19 on to an enthusiastic eater at a wet market.

But just as in the Pied Piper example, role transformations occurred in the COVID-19 environment. The basic narrative of the people of Wuhan as the primary victims, the Chinese government as the rescuer, and the bat as the persecutor/perpetrator no longer stands as firmly as it did in January. Interestingly, Chinese authorities also think of COVID-19 as a conflict. According to Richard McGregor of the Lowy Institute, the “Chinese character for plague sounds similar to the character for military campaign,” and it is thus unsurprising that “the official [Chinese] narrative of the COVID-19 crisis took on strong war-like undertones.” This origin story was unacceptable to China, so it set out to change the roles and characters in the drama triangle. The transformation of the narrative is partly due to Chinese (and Russian) disinformation and partly due to the facts on the ground.

COVID-19 and Disinformation

In January and February 2020, the United States and the European Union sent medical aid and scientists to China to help fight COVID-19. A month or two later, Europe was overrun by COVID-19 while at the same time China claimed that it stabilized COVID-19 back home. Then, as a show of power, China sent planeloads of medical assistance decked out with Chinse flags to Europe. In a Karpmanian transformation, yesterday’s victim became today’s rescuer, and yesterday’s rescuer became today’s victim.

Disinformation about COVID-19 has ballooned since mid-March 2020 to the point where the WHO is talking about an “infodemic.” In recent months, Chinese state actors actively polluted Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and other neutral online platforms to win the COVID-19 information war. While disinformation is nothing new, the severity of the triple crisis related to COVID-19 means that the stakes are high.

One of the key characteristics of Chinese COVID-19 narratives is that it has largely been constructing a positive image for itself – the global rescuer – while denigrating the image of the West. Beijing’s rescuer narrative frequently suggests that the Chinese model of authoritarianism is superior to Western democracy as the latter model fails to deal with COVID-19. Absent in the Chinese narrative are references to democracies that have fared well, such as Australia, Japan, Norway, South Korea, and New Zealand.

The rescuer narrative suggests that China is a powerful player with the ability to take over responsibility from areas previously occupied by the United States, the European Union, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Chinese narratives portray the Western world as either victims or persecutors/perpetrators. But here, Chinese disinformation efforts have been central to this characterization. For example, Lijian Zhao, a spokesperson for the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, implied that COVID-19 might have been brought into Wuhan by the U.S. Army. The European Union also recently accused China of spreading a “huge wave” of COVID-19 falsehoods such as stories about European healthcare workers abandoning their patients and French lawmakers using racist slurs against the head of WHO.

Yet, Chinese disinformation is not just about manufacturing falsehoods. In June 2020, Twitter removed over 170,000 social media accounts that China, Russia, and Turkey allegedly used to spread propaganda. The majority of those accounts – 150,000 – were so-called “amplifier” accounts used to boost content. As argued throughout Nina Jankowicz’s new book How To Lose The Information War, disinformation is not merely about spreading fake news. In fact, amplifying existing narratives that “sow doubt, distrust, and discontent” is often far more successful. A recent study by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) of some 24,000 Twitter accounts suggests that China’s response to the accusation of racism against African immigrants in the wake of COVID-19 was to amplify attention to George Floyd’s brutal death and police brutality in the United States.

The Way Forward

Firstly, the United States needs to assert itself as the rescuer more actively, or at the very least, move towards the center of Karpman’s drama triangle.

Following Karpman, the three basic roles of a conflict are never set in stone. In the battle against Chinese disinformation about COVID-19, the United States needs to do five things:

Firstly, the United States needs to assert itself as the rescuer more actively, or at the very least, move towards the center of Karpman’s drama triangle. That means the United States needs to unbundle itself from the perpetrator/persecutor and victim roles. Superpowers depend on military might, a strong economy, advanced technology, and soft and diplomatic power to influence other states. Yet, it is impossible to play a superpower if the audience perceives the United States as a persecutor/perpetrator or victim. The United States can shed the victim’s role if it effectively manages the COVID-19 crisis and changes the facts on the ground. So far, the United States has failed to do so, and allies view it as the epicenter of the pandemic rather than the epicenter of power. By the end of October, COVID-19 has killed over 233,713 Americans – the equivalent of 9/11 occurring 78 times – and between April and June the U.S. economy contracted by 32.9 percent, the most significant blow since the Great Depression. The United States looks more like a victim in need of being rescued rather than a superpower. While the United States should identify and create opportunities to lead the global battle against COVID-19, especially in technology and science, it is essential to be ready, once it becomes available, to facilitate and push for the widespread distribution of an affordable vaccine.

Secondly, given the reach of China’s disinformation and the extent and impact of the COVID-19 crisis on the United States, Washington cannot be in this fight alone. The United States has largely adopted unilateral measures to deal with COVID-19 rather than leading a global effort. By withdrawing from the WHO and alienating the European Union, the United States is losing the ability to situate itself as a global rescuer. NATO needs to develop a collective strategy that brings together thirty allies, nearly one billion people, and about half of the world’s military and economic might. The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue consisting of the United States, India, Japan, and Australia should also play a more active role.

Thirdly, the United States should clean up the information ecosystem at home to make the country less vulnerable to outside disinformation. As mentioned, many Chinese narratives merely amplify home-grown American falsehoods ranging from claims that hydroxychloroquine is the cure to COVID-19 to conspiracy theories questioning the importance of masks. A recent report titled “Retweeting Through the Great Firewall” pointedly warned that U.S. President Donald J. Trump should stop spreading misinformation as a political weapon, as the United States “risks losing ground as a credible consistent and trustworthy international voice seeking to call out disinformation and propaganda.”

Fourthly, fighting disinformation by removing fake content created by malign actors is often likened to whack-a-mole. What is needed is inoculation to disinformation, but that can only happen if the United States restores self-confidence in liberal democracy, the country’s institutions (especially the media and healthcare system), and science.

China exploits COVID-19 to give the impression that authoritarian systems are better equipped than democracies to manage the crisis. Too many Americans are saying “I can’t breathe” as a result of police brutality or COVID-19. Even before COVID-19, former U.S. Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, Nicolas Burns, interviewed former U.S. Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, and asked her about the greatest threat to the United States. He expected her to say China or Russia. According to Burns, she replied, “we have lost our self-confidence…we in America, and we in the West, have lost the belief that there is something to defend.” In short, liberal democracy is under significant threat and the system needs fixing.

Key U.S. institutions that should be central to fighting COVID-19 are also under attack. Many of those attacks come from within, generating drama triangles inside the United States ready for exploitation. President Trump regularly refers to CNN, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and other media outlets as “fake news.” He also sows doubt about U.S. scientists like Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases who should be leading the COVID-19 response. As a result, some Americans do not trust those institutions anymore. They have turned to conspiracy outlets like Infowars and conspiracy theorists to ‘educate’ them about COVID-19 (some even say it is a “hoax”). One cannot wage war against COVID-19 under those conditions.

Finally, like China, the United States should treat COVID as a conflict. According to Lea Gabrielle, Special Envoy and Coordinator of the U.S. State Department’s Global Engagement Center (GEC), China recently “invested an estimated $10 billion in its global information strategy.” GEC’s budget for 2019 was a mere $52.4 million, and it operates with a limited mandate as it should strictly focus on countering propaganda and disinformation from foreign threats. By comparison, the United States spent $52 billion in 2019 waging war in Afghanistan. Other government agencies are focusing on disinformation, such as the FBI’s Foreign Interference Task Force, but experts like Nina Jankowicz complain that US efforts are “disparate and uncoordinated.” Cleaning up the information ecosystem requires greater resources and a more centralized approach.

Dr. Leon Hartwell, Title VIII Transatlantic Leadership Fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) in Washington D.C. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description:From The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Pied Piper of Hamelin, by Robert Browning

Photo Credit: Illustration by Kate Greenaway

Much like Covid-19, the demands of further modernization/globalization have, of late, produced crises throughout the world; this, due to:

a. The political, economic, social and value “change” demands that further modernization/ globalization requires of the world’s states and societies and

b. The resistance to such change which comes from many of the world’s populations today. (Now even from the Global North; this, as the recent Brexit and election of Donald Trump confirms?)

Accordingly, might we (a) be able to view the narratives, the strategies, the responses, etc., of the various parties having to confront these further modernization/globalization crises; this, (b) also from the perspective of the conflict/drama “triangle” discussed by our author Leon Hartwell above?

For example:

1. In the past:

a. The “persecutor,” BOTH AT HOME AND ABROAD, might have be seen as those (generally conservative?) population groups that stood in the way of the political, economic, social and value changes required by further modernization/globalization.

b. The ‘victims,” in this scenario, might have been identified as (a) average citizens who, both at home and abroad, were being denied the opportunities that could have been afforded to them by further modernization/globalization and as (b) these populations’ countries as a whole; this, given that these countries’ national security would be compromised by not taking full advantage of the opportunities afforded by further modernization/globalization. (Requires, both at home and abroad, some degree of political, economic, social and/or value change?) Thus, from this perspective:

c. The “rescuer” was seen as those (generally progressive?) business, government and academic “elites, to wit: those who worked to achieve the political, economic, social and/or value changes required by further modernization/globalization. (And, thus, required by national security?)

2. Now compare this to today when — in both Global North and in the Global South —

a. The “rescuer,” identified at “1c” above, is often portrayed as the “persecutor,”

b. The “victim” is again be identified as the population and the nation or society as a whole but, in this case, because one’s traditions and culture are (in fact) under assault by these progressive “elites.” Thus, in this scenario,

c. The “persecutor,” identified at “1a” above, is portrayed as a “cultural champion” and thus as the “rescuer.”

Question:

If the narrative portrayed in item “2a-c” “wins” — in the Global North and/or in the Global South — then will “we” — and/or “they” — be able to adequately deal with such things as Covid-19, and indeed the other national security challenges we are likely to face today and going forward? (In this “other national security challenges” category, of course, include staying ahead of competitors such as China.)

Let us consider these “narrative” questions from a somewhat different point-of-view; this being, from the perspective of:

a. China being seen as the “defender” (engaged, thus, in what might be called “resistance warfare?”) and:

b. The United States being seen as, shall we say, the “aggressor” (engaged, thus, in what might be called “revolutionary” or “transformative” warfare?)

As a means of supporting this suggestion, let me offer the following excerpt from Jennifer Lind and Daryl G. Press’ Foreign Affairs (the Mar/Apr 2020 issue) article entitled “Reality Check: American Power in an Age of Constraints:”

Lind and Press:

“For the past three decades, as the United States stood at the pinnacle of global power, U.S. leaders framed their foreign policy around a single question: What should the United States seek to achieve in the world? Buoyed by their victory in the Cold War and freed of powerful adversaries abroad, successive U.S. administrations forged an ambitious agenda: spreading liberalism and Western influence around the world, integrating China into the global economy, and transforming the politics of the Middle East. …

This approach to foreign policy was misguided even at the peak of American power. As the endless wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and Russian interventionism in eastern Europe have shown, adversaries with a fraction of the United States’ resources could find ways to resist U.S. efforts and impose high costs in the process.”

Question:

If we come to “know the enemy and ourselves” in the manner portrayed by Lind and Press above (if their such depictions are both accurate and correct), then how might this perspective help us re: our narrative issues, for example, with our such issues relating to Covid-19?

(Here I am thinking that our opponent’s “narrative” efforts may be consistent with Lind and Press’ suggestion that these are part of an overall goal and plan to [a] “resist efforts by the U.S. to spread liberalism and Western influence around the world” and to [b] “impose high costs on us in this process.”)

From our article above:

“China exploits COVID-19 to give the impression that authoritarian systems are better equipped than democracies to manage the crisis. Too many Americans are saying ‘I can’t breathe’ as a result of police brutality or COVID-19. Even before COVID-19, former U.S. Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, Nicolas Burns, interviewed former U.S. Secretary of State, Condoleezza Rice, and asked her about the greatest threat to the United States. He expected her to say China or Russia. According to Burns, she replied, ‘we have lost our self-confidence … we in America, and we in the West, have lost the belief that there is something to defend.’ In short, liberal democracy is under significant threat and the system needs fixing.”

Thought:

With regard to this such loss of our self-confidence, this suggested loss in our belief that there is something to defend, to observe this first-hand — and indeed to confirm this such “sea-change — to do this, do we need only look at the dramatic “sea-change” in the U.S. foreign policy that has occurred with the Trump administration. Wherein, for the first time in many, many decades we have:

a. Moved away from an agenda of spreading liberalism and Western influence around the world and, in the place of same, have:

b. Moved to embrace (re-embrace?) the earlier concept of “diversity,” “sovereignty” and “equality?”

From President Trump’s remarks to the United Nations in 2017:

“We do not expect diverse countries to share the same cultures, traditions, or even systems of government. But we do expect all nations to uphold these two core sovereign duties: to respect the interests of their own people and the rights of every other sovereign nation. This is the beautiful vision of this institution, and this is foundation for cooperation and success.

Strong, sovereign nations let diverse countries with different values, different cultures, and different dreams not just coexist, but work side by side on the basis of mutual respect.”

From President Trump’s remarks to the U.N. in 2019:

“The future does not belong to globalists. The future belongs to patriots. The future belongs to sovereign and independent nations who protect their citizens, respect their neighbors, and honor the differences that make each country special and unique.”

Bottom Line Thoughts — Based on the Above:

1. If every state, society, civilization, culture, tradition and every system of government (to include those of China) — however different these are from our own — if these are all as correct, precious, valid and legitimate as our own, then this, indeed, would seem to be a radical “step down” for the United States — and a 180 degree “about-face” from our previous understanding and contention re: American/Western preeminence and exceptionalism.

(No wonder our loss of self-confidence?)

2. As to the possible adverse strategic consequences of this such move by the Trump Administration, consider the following from a January 2016 paper “Unconventional Warfare in the Gray Zone” by authors Joseph L. Votel, Charles T. Cleveland, Charles T. Connett, and Will Irwin:

“Advocates of UW first recognize that, among a population of self-determination seekers, human interest in liberty trumps loyalty to a self-serving dictatorship, that those who aspire to freedom can succeed in deposing corrupt or authoritarian rulers, and that unfortunate population groups can and often do seek alternatives to a life of fear, oppression, and injustice. Second, advocates believe that there is a valid role for the U.S. Government in encouraging and empowering these freedom seekers when doing so helps to secure U.S. national security interests.”

(Question: Is this such contention, “tool,” understanding and approach invalidated — and/or made exceptionally less capable or less useful — this, given the Trump Administration’s “sovereignty”/ “diversity”/”equality” concept and stance?)

Here is a question, one that:

a. While in great discussion in recent years,

b. Would not seem to have been addressed much recently:

The Question:

If the nation-state (indeed any nation state, even that of the U.S. and/or China, and whether such nation-state is democratic, authoritarian or something else); if the nation state is no longer able to adequately provide for the needs of its citizens (exs: re: the pandemic and/or the global economy)

“The most momentous development of our era, precisely, is the waning of the nation state: its inability to withstand countervailing 21st-century forces, and its calamitous loss of influence over human circumstance. National political authority is in decline, and, since we do not know any other sort, it feels like the end of the world. This is why a strange brand of apocalyptic nationalism is so widely in vogue. But the current appeal of machismo as political style, the wall-building and xenophobia, the mythology and race theory, the fantastical promises of national restoration – these are not cures, but symptoms of what is slowly revealing itself to all: nation states everywhere are in an advanced state of political and moral decay from which they cannot individually extricate themselves.”

(See the Thursday, April 5, 2018 Guardian article entitled “The Demise of the Nation State” by Rana Dasgupta.)

And if, accordingly, the only real “cure” to everyone’s problems is to be found (a) not within the individual states themselves, but, rather, (b) by way of something more along the lines of “global governance” or “global cooperation,”

Then are we, in continuing to try to address our problems via the nation-state’s mechanism:

a. Simply trying to avoid the inevitable. And, thereby, both knowingly and willingly

b. Subjecting our own population, and that of the rest of the world, to the exceptionally well-known risks, costs, etc., associated with such behavior, for example, those associated with such things as nationalism?

(How then might the “triangle,” the “narrative,” etc., play out in the scenario that I have described above? Specifically, who is the “perpetrator, the “rescuer,” the “victim,” etc., in this, our new/old reality?)

WOW This article is not faring well in current times.