[King’s] autobiography is superb reading for those interested in leadership, and it contains two specific documents that encapsulate King’s leadership and remain testaments for senior military leaders today.

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, tensions between the United States and the Axis Powers spiked, presenting the U.S. Navy with daunting challenges, including the prospect of a nightmare scenario of facing a two-ocean naval war alone if the Nazi advance continued and Great Britain fell. The Navy required a special officer to lead it after Pearl Harbor, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt chose Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King. A complex person and a product of his time, King was a hard-nosed and irascible sea dog who was unswerving in his convictions and strategic views. He was a strict disciplinarian who popular myth held was so tough he “shaved with a blowtorch.” After becoming the Chief of Naval Operations, King supposedly growled: “When they get in trouble, they send for the sons-of-bitches.” When asked if he actually said this, the quick-witted King replied that he had not, but he would have if he had thought of it. A gruff exterior and volcanic temper, however, hid a man who cared deeply about the Navy, its sailors, and his shipmates. Just as important, he had a first-class strategic intellect. These traits are apparent in King’s autobiography Fleet Admiral King: A Naval Record, which details the formative experiences that prepared him to lead the U.S. Navy during its greatest trial. His autobiography is superb reading for those interested in leadership, and it contains two specific documents that encapsulate King’s leadership and remain testaments for senior military leaders today.

In early 1941 Admiral King was in command of the Atlantic Squadron, which subsequently became the Atlantic Fleet. That year the Navy moved from peacetime operations to being on a war footing, and it suffered from the typical teething issues inherent to such a transition of rapid expansion and shedding the peacetime mindset of micromanagement. Contemporary naval operations required large decentralized operations, and King knew this. He also knew that these operations required a specific approach to leadership. This knowledge caused him to adopt the command philosophy needed for victory in World War II, which he set out as a fleet order on January 21, 1941. He refined and reinforced this first document in another fleet order, dated April 22, 1941. (Both documents can be found at the link below.)

King’s two fleet orders are succinct studies in what today we would call the philosophy of mission command. In his first fleet order, King directed that commanders must be “habitually framing orders and instructions to echelon commanders so as to tell them ‘what to do’ but not ‘how to do it’ unless particular circumstances demand.” For this approach to work, however, trained subordinates had to exercise disciplined initiative, which King referred to as “initiative of the subordinate.” He also knew he had to overcome Atlantic Fleet subordinates’ reluctance to act, as they were “accustomed to detailed orders and instructions.” At the same time, King, ever the disciplinarian, did not give carte blanche for subordinates. In his second fleet order, he made it quite clear that “initiative means freedom to act, but it does not mean freedom to disregard or to depart unnecessarily [italics original] from standard operating procedures or practices or instructions.”

On the second-to-last day of the same month as Pearl Harbor, King assumed command as the Commander-in-Chief, United States Fleet (COMINCH), and on March 18, 1942, King also became the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO). Only King and General of the Army George C. Marshall, Chief of Staff of the Army, has ever wielded so much power with respect to manning, training, and equipping a U.S. service and commanding it during combat. Throughout the war, King demanded the Navy continue its traditional approach of mission command and disciplined imitative, which he described so well in his memos. As King’s command philosophy took hold throughout the Navy, it helped create shared understanding and build cohesive teams through mutual trust. Similarly, World War II-era Navy commanders learned to provide clear commander’s intent and successfully and repeatedly demonstrated a willingness and ability to accept prudent risk and win.

King’s philosophy was the same from his most senior subordinates to ship commanders, although service politics intruded at times. For example, there was often friction over the strategic direction of the Pacific War and the resultant division of resources between Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz – King’s primary subordinate in the Pacific and theater commander of the Pacific Ocean Areas – and General of the Army Douglas MacArthur – Marshall’s primary subordinate in the Pacific and the theater commander of the Southwest Pacific Area. King constantly pushed Nimitz on the conduct of the war in the Pacific, and King was angry when Nimitz compromised with MacArthur.

King’s memoirs tell all of these stories and more, detailing a determined leader who aggressively pushed his subordinates and often his superiors; however, King got results.

King’s memoirs tell all of these stories and more, detailing a determined leader who aggressively pushed his subordinates and often his superiors; however, King got results. For example, when King was a Captain and the skipper of the aircraft carrier USS Lexington, he participated in the Navy’s annual fleet exercise. His lethal crew not only destroyed the opposition force, but also helped refine carrier operations. Interestingly, the Admiral and Chief Umpire of the fleet exercise asked King if he was “trying to bomb the Chief Umpire?” King laughed this off saying that his flyers did not know that it was the Admiral’s ship they were bombing. Perhaps King knew and was coyly dodging the question, or perhaps he was just covering for his pilots whose inadvertent bombing of the umpire struck him as funny. Either way, one could see an early version of Maverick’s flybys from the movie Top Gun, demonstrating that King rewarded risk-taking and understood the bravado necessary for naval aviation.

After he commanded the Lexington, King attended the Naval War College. In preparation for the annual wargame between the U.S. Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy, the Department Head offered King the command of the U.S. Pacific Fleet if he followed the War College President’s desired route of attack. Characteristically, King replied “if ordered to use the wrong solution he would gladly do so…rather than miss the chance to command such a fleet.” King proved his abilities as a fleet commander during the war game but, as he often did, made life difficult for his superiors, especially when he was told how to do something rather than just what to do.

King’s strategic insight and ability to successfully argue against conventional wisdom and with senior leaders later proved to be essential when he was a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Combined Chiefs of Staff. In these roles, he often fought with other members of the U.S. Chiefs of Staff as well as the British Chiefs of Staff Committee to secure more resources for the Pacific War. He irritated President Franklin D. Roosevelt on a few occasions, sometimes argued with Secretary of the Navy William Franklin Knox, and routinely fought with Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal. During strategic debates with the British, he even crossed verbal swords one of the most formidable statesmen and strategists of World War II Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill, often successfully. King won many of these strategic arguments, and the historical record shows he was right far more often than he was wrong.

There is a rich history of new senior leaders taking broken naval and military units in dark times, such as General Ulysses Grant galvanizing the Army of the Potomac in its successful Overland Campaign, Admiral Chester Nimitz restoring the confidence of the Pacific Fleet after Pearl Harbor, and General Matthew Ridgway rebuilding US Eighth Army in Korea. Thomas B. Buell’s biography of King, King’s Official Reports, Samuel Eliot Morison’s fourteen-volume History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, and many others tell the tale of King’s leadership. As the two documents mentioned above demonstrate, Admiral King’s leadership, first of the Atlantic Fleet and then the entire U.S. Navy throughout World War II, underscore the timeless importance of the philosophy of mission command and the disciplined initiative it fosters. Today and tomorrow’s senior leaders can learn much from reading King’s command philosophy and his autobiography, from fostering and employing mission command to speaking truth to power.

Admiral King’s January and April 1941 Fleet Orders

Jonathan Klug is a Colonel in the U.S. Army, a faculty member in the Department of Military Strategy, Planning, and Operations at the U.S. Army War College and an Associate Editor with WAR ROOM. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

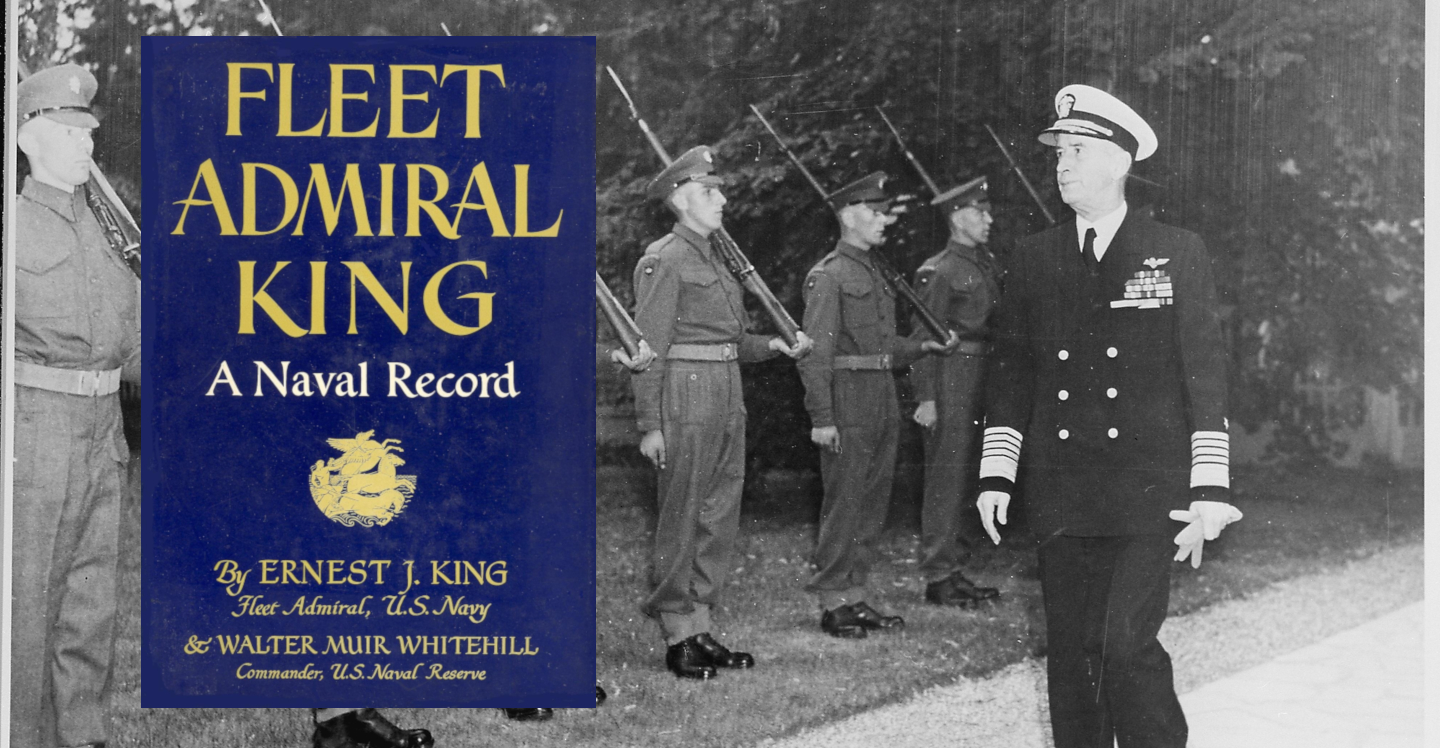

Photo Description: Fleet Adm. Ernest J. King, U. S. Navy, arrives at the residence of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill for a dinner given by the Prime Minister for President Truman and Soviet leader Josef Stalin during the Potsdam Conference in Germany. The Guard of Honor, formed by the Scots Guards of the British Brigade of Foot Guards, flanks pathway leading to the house.

Photo Credit: National Archives and Records Administration. Office of Presidential Libraries. Harry S. Truman Library.

Other releases in the “Dusty Shelves” series:

- CARTER’S FAILED STRATEGIC GAMBLE: GENERAL HUYSER’S MISSION TO TEHRAN

(DUSTY SHELVES) - KOREA ON THE BRINK: GENERAL JOHN WICKHAM AND POLITICO-MILITARY CRISIS MANAGEMENT

(DUSTY SHELVES) - FIGHTING BY MINUTES, THIRTY YEARS LATER

(DUSTY SHELVES) - THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER (1988): THE FORGOTTEN PRIMER ON LEADERSHIP

(DUSTY SHELVES) - RIDGWAY’S KOREAN WAR

(DUSTY SHELVES) - ALL WAR IS LOCAL: ANTHONY QUAYLE’S EIGHT HOURS FROM ENGLAND

- POST-WAR TRUTH TELLING: THE WAR MANAGERS

- DYE: EXALTING THE TAIL OF THE AIRPOWER TOOTH

(DUSTY SHELVES) - PEACE FORMS: LOOKING BACK TO THE FUTURE OF WAR AND ANTI-WAR

- SHERMAN: THE OUTLIER OF INTERWAR “ATLANTIC” AIR THEORY?

(DUSTY SHELVES)

Great book, but must be read today with the input of books like “The second most powerful man . .” (Leahy biography), etc. king was a great leader but he was not, as suggested, at the forefront of strategic policy

I would caution anyone reading modern “revisionist” history to be very selective, and not to unilaterally accept them as accurate. The Leahy book, for example, draws all the wrong conclusions.