Climate change is affecting individuals, communities, and states worldwide, and they are changing in response.

It is 2035, and you are planning for NATO’s STEADFAST DEFENDER 2036. You were stationed in Europe in the early 2020s, so you know what to expect. Then, the loggie walks in and says there is a problem with fuel and electricity availability. The European Union now predominantly uses electricity and hydrogen for vehicles and airplanes, so gas, diesel, and JP-8 are all in short supply on the continent. Plus, host nation electric grids are already maxed out due to everything switching over to electricity. What you thought you knew in the 2020s simply doesn’t hold anymore. Climate change is affecting individuals, communities, and states worldwide, and they are changing in response.

Amongst military personnel, the term “climate change” has sometimes carried a negative connotation. Some military personnel perceive it as a politically-charged topic and thus best avoided in work environments, and others may have concluded that being environmentally conscious must negatively affect operations. If you are the frozen middle still resistant to including climate change in your future planning, and the President’s and Secretary of Defense’s declaring climate change a risk to national security and recently released federal adaptation plans are not enough to thaw your position, you need to consider the effects and changes already occurring domestically, internationally, and in the for-profit commercial sector—all of which the DoD relies on to ensure national security.

The DoD is already experiencing highly visible and expensive effects from rising temperatures and the resultant increases in extreme weather events. In 2018, hurricanes caused $3.6B in damage to U.S. Marine Corps installations, $4.7B in damages at Tyndall Air Force Base and forced the relocation of F-22 training and operations, and increasingly frequent hurricanes are delaying training and testing at the Atlantic Undersea Test and Evaluation Centers and Eastern Range. In 2019, melting of record snow fall flooded Offutt Air Force Base causing $654M in damage. Wildland fires continue to affect operations at Vandenberg Space Force Base, Western Range, and Point Mugu Sea Range. The DoD has 79 installations that are either currently, or will be in the next 20 years, adversely effected by climate change through recurring flooding, drought, desertification, wildfires, or thawing permafrost. Recovering from these events is already putting pressure on a flatlined DoD budget, but the strategic impact of climate change is far more than just the cost of repairing installations.

Since the start of the industrial revolution and associated increased greenhouse gas emissions, the earth’s average surface temperature has risen over two degrees Fahrenheit. July 2021 was the hottest month ever on record. Much of that increase has been in just the last three decades as more countries go through their own industrialization Russia and China have even acknowledged the change.

Recent studies establish a link between climate change and increased conflict that can hasten the failure of weak and failing governments. Temperature and rainfall changes contributed to the downfall of Rome. Four considerably cooler periods between the 15th and 18th centuries “provoked or worsened regional food shortages, famines, rebellions, wars, and outbreaks of epidemic disease.” Today, the World Health Organization estimates climate change will cause an additional 250,000 deaths a year due to malnutrition, malaria, diarrhea, and heat by 2030. Combine the changing climate with how water control has been used as a coercion tactic for thousands of years, and it is a recipe for increased international conflicts and mass migration. Consider the Iranians that recently rioted near the Iraqi border over water shortages. Or that Lake Victoria may stop providing water to the Nile River in a decade, and Ethiopia has started filling its new Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam on the Blue Nile. Maintaining the new reservoir could reduce water to Egypt by more than a third, causing a 72% reduction in arable land and $51B in lost agriculture each year. On the other end of changing precipitation levels, China is having difficulty managing its over 98,000 dams protecting 1.4B people due to increased rainfall. How easy would it be for one of these droughts or floods to change regional stability or cause a mass migration that threatens U.S. national security?

With rising temperatures, the Arctic Sea ice is melting at faster rates and states are posturing for access and control. The Northern Sea Route along the Russian coast is now seasonally navigable; and even if temperatures stay below the Paris Climate Accord’s goal, the Northwest Passage along Canada and Arctic Bridge across the North Pole will be navigable by standard ships part of the year. China is preparing for these changes by becoming an Arctic Council observer in 2013 and releasing China’s Arctic Policy in 2018 that declared itself a near-Arctic state. China is planning a Polar Silk Road as part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) for a sealift route from Eastern China to the North Sea via the Arctic Ocean. Russia is also preparing for increased access with its 50 icebreakers and dispatching a floating 80-megawatt nuclear reactor for oil exploration in the region. In contrast, the United States has only two old heavy icebreakers (and only one currently seaworthy), and Congress only just recently funded two more.

The international community has started to acknowledge these and many other effects of climate change and is working to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, especially carbon dioxide. In 2017, China and the European Union signed a joint statement highlighting increased stress on ecosystems due to climate change and noted the “detrimental impacts on water, food, and national security have become a multiplying factor of social and political fragility.” And although China continues to outpace the word in coal power plant construction, the government plans to peak carbon emissions by 2030 and be carbon-neutral by 2060. Even Russian President Vladimir Putin, who said in 2013 that warmer temperatures just meant Russians would “spend less on fur coats,” recently said permafrost melting could have “very serious social economic consequences.” Now, Russia’s national security strategy references climate change nine times and “as a key reason for environmental emergency situations like wildfires, flooding, as well as spreading of infectious diseases;” and Russia plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 70% by 2030.

What will Russia do when 60% of its gross domestic product from oil and gas exports evaporates?

The European Union has already reduced greenhouse gas emissions by 24% from 1990 levels, even with 60% economic growth, and it has now increased its reduction goal to 55% by 2030. As part of the reduction, twenty-four countries are banning diesel vehicles, with 13 banning internal combustion engines in the next decade. These decisions will have significant effects on climate, the international economy, and international security. Consider, for example, that the European Union imports 61% of its energy sources, and Russia is the lead supplier to the European Union of crude oil, natural gas, and solid fossil fuels. What will Russia do when 60% of its gross domestic product from oil and gas exports evaporates? Or on a larger global scale, what about developing nations that, even minus China’s contribution, are still 40% of the global greenhouse gas emissions? Can they afford to skip the traditional greenhouse gas intensive growth period without assistance from developed nations?

If you still think climate change is just a politician’s campaign slogan, the for-profit commercial sector does not. Electric car sales worldwide could surpass sales of gas and diesel cars as early as 2040, and the international automobile industry is already changing to meet demand. For example, General Motors accelerated its electric vehicle plan with a $27B investment to have 30 all electric models by 2025, at which point 17 companies will have debuted 100 all-electric vehicles in the United States. The heavy hauler market is also changing with Daimler (the world’s largest heavy haul truck manufacturer) planning to switch to zero-emission vehicles entirely by 2036. Is the DoD adequately preparing for the global shift away from the internal combustion engine and associated supply industries? Or does the DoD want to maintain an exquisite internal combustion engine capability?

For sealift, A.P. Moller-Maersk plans to reduce emissions by 60% by 2030 and be net-zero by 2050. As part of this reduction, they will start operating the first carbon-neutral vessel running on methanol in 2023, seven years earlier than planned. Maersk acknowledges sourcing sufficient methanol supply will be a significant challenge and calls on “fuel suppliers, technology partners and developers to ramp up production fast.” If the largest sea-cargo company in the world is changing fuel sources, the rest of the industry will be forced to follow. Does the U.S. Navy need to follow as well?

The aviation industry is also changing. Rolls-Royce recently expanded its hybrid-electric aircraft engine research with Purdue University. Boeing is working toward a 50% reduction in 2020 airplane energy requirements by 2050. Airbus is investing in hydrogen propulsion technology to be zero-emission by 2035. By 2050, United Airlines’ goal is to be 100% green, and American Airlines will be net zero. Additionally, with investors like Toyota, JetBlue, and Uber, Joby Aviation’s electric air taxi is on a path to change regional air travel by 2024. Is the U.S. Air Force resourced to make similar changes?

Fundamentally, the energy market is changing. Shell and British Petroleum plan to be net zero by 2050. Exxon Mobile just added two climate change focused members to its board of directors to expand the company’s renewable sector. Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, and Algeria are all trying to diversify their economies away from relying on hydrocarbon production. The DoD used an estimated 88 million barrels of fuel in 2020—will those supply chains be available in 2035 or 2050? Also, what about the 1.2M people that work in the U.S. oil and gas industry? Is the federal government going to need to assist that workforce transition at the expense of other discretionary federal spending?

Underlying all these changes and a potentially $50T market are supply chains with a hidden security risk. Rare earth elements are required for most green technology changes, and China controls the world’s rare earth element market (mining, refining, and component manufacture). China also controls 80% of solar panel production, and they are financing and building green projects in locations like Pakistan and Argentina to expand BRI’s coercive power. While China produces up to 70% of some electronic markets, it only has 7.6% of the global semiconductor market; but, 60% of the world’s semiconductor manufacturing is just off the coast in the Republic of China (Taiwan). Is the world prepared if China adds majority control of the semiconductor market to their coercion toolbox?

In the past, the DoD environmental efforts have been to improve energy efficiencies of buildings, infrastructure, or platform operational energy efficiencies with financial savings as the driver. That narrow motivation is slowly changing as the strategic effects of climate change become more apparent and as the services shift research priorities to climate-related topics—for example, how to power electric vehicles on the battlefield or the first airworthiness rating to a manned electric aircraft. Still, this slow pace is not keeping up with either adversary preparations or changing commercial markets. President Biden’s Executive Order needs to be the inflection point for DoD members to start actively planning for the changing climate at all levels. Senior leaders are saying we need to change. The youth entering the DoD know we need to change. Are you the one frozen in an outdated perspective that climate change does not affect national security?

Matthew Beverly is a Colonel in the U.S. Air Force, an Instructor in the Department of Military Strategy, Planning, and Operations at the U.S. Army War College, member of the U.S. Army Climate Change Working Group, and is a registered professional engineer in the state of Colorado.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

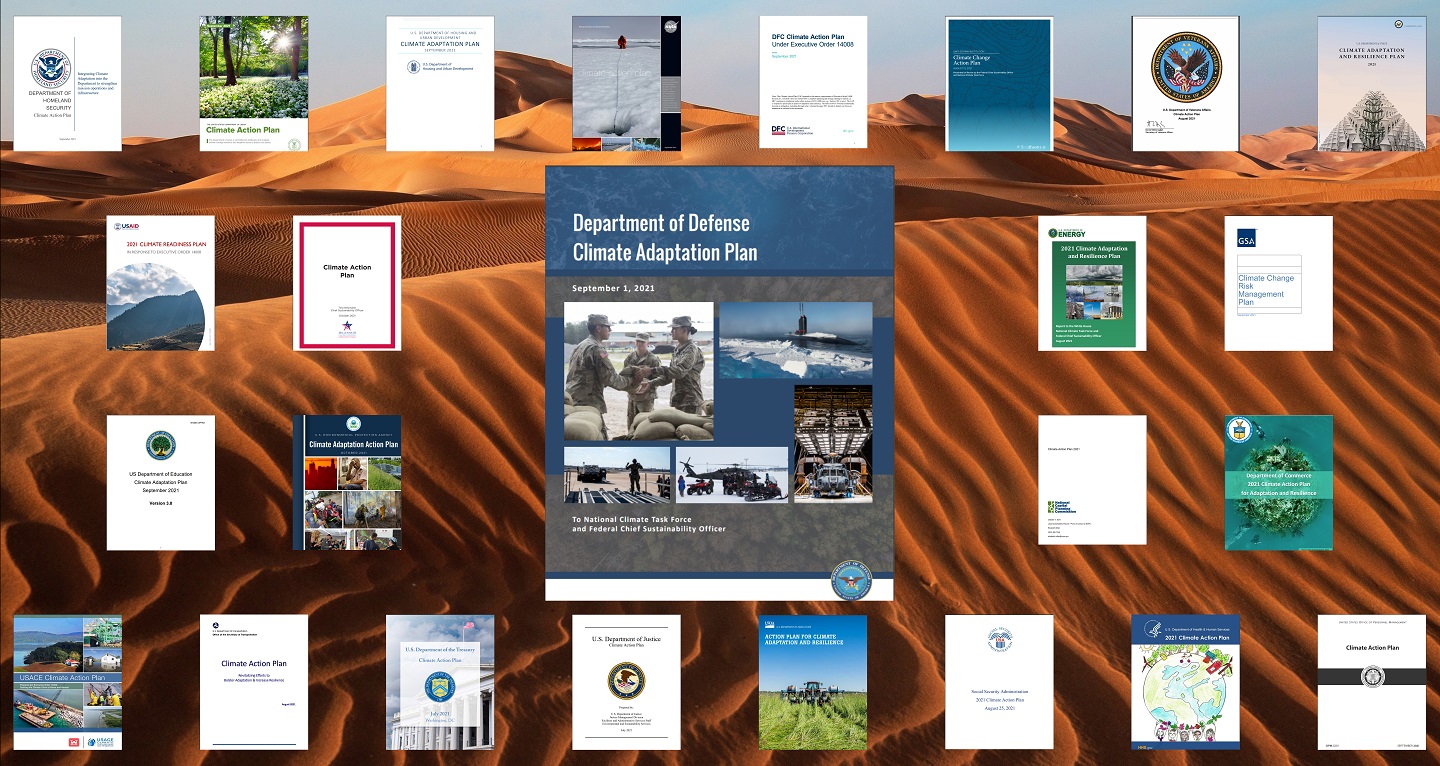

Photo Description: As directed by President Biden’s January 28, 2021, Executive Order 14008, major Federal agencies are required to develop an adaptation and resilience plan to address their most significant climate risks and vulnerabilities. On October 7, 2021, the White House announced the release of more than 20 Federal Agency Climate Adaptation and Resilience Plans. As part of these efforts, agencies will embed adaptation and resilience planning and implementation throughout their operations and programs and will continually update their adaptation plans.

Photo Credit: https://www.sustainability.gov/adaptation/

This is a very timely, well researched and thought provoking article. America has definitely failed to keep up with changing trends and strategic technology. Congress needs to wake up and allow the military to develop cutting edge systems and stop funding outdated technology to protect industries and military bases in their congregational districts. This article should be a wake up call before it is too late.

Thank you Matthew Beverly, this quite an eye opener. All levels of government and civilians need to wake up and prepare for change that is coming. Climate change will lead to instability in all countries, some more than others. I didn’t know that Taiwan had 60% of semiconductor manufacturing, this is definitely a target for China. With the recent over flight by the Chinese airforce I can see that it could be a prelude to an invasion by China against Taiwan.