As daunting as the future threat is, it’s the current (and projected) fiscal environment, the partisanship, and the seeming inability of national leaders to address these concerns, that are the biggest issues the military faces.

In a complex and dangerous world, the U.S. Army struggles with a persistent, strategic challenge: how to allocate limited financial resources to provide an effective ground force. Instead of business as usual, the Army’s leadership must seize the opportunity to adopt a strategic culture that accepts austerity as a given, and that embraces a new, more holistic approach to resource decision-making. Failure to take the long view and to make tough decisions now will bring the Army’s future capability and relevance into question. Conventional wisdom dictates that more resources are needed to make the Army whole again, but in this case, as in many, conventional wisdom is wrong. Higher troop numbers and increased budgets will not prove helpful in the current fiscal and political environment unless they are sustainable. Unfortunately, current trends and the present political climate show they are not.

The recent presidential campaign, election, and post-election unrest are just the latest indicators of a significant schism in the electorate between two fundamentally different and diverging political worldviews. This split has resulted in less “across the aisle” cooperation and more difficulty passing legislation as deficit and debt levels climb.

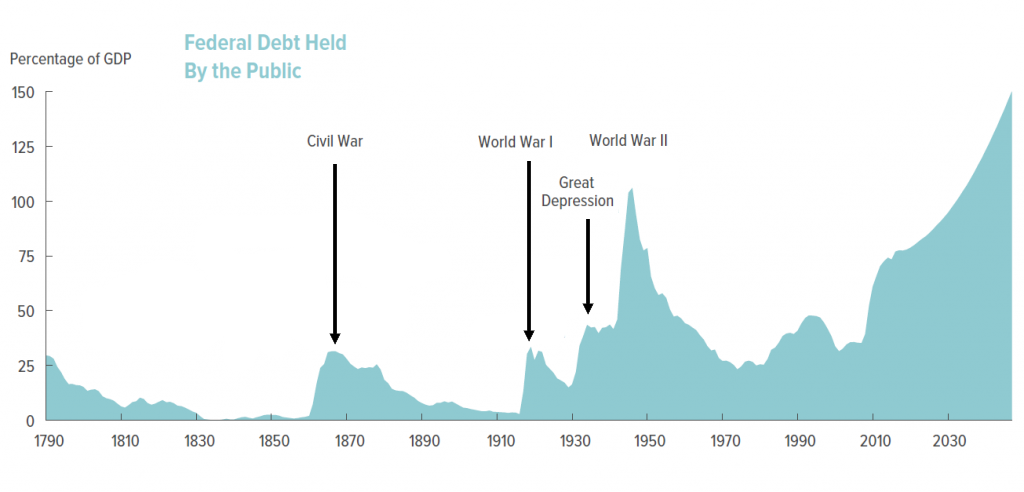

The growth in debt arises primarily from mandatory spending due to an aging population, higher health care costs, and rising interest payments on the debt. However, the polarized political climate and the consequent inability to arrive at a budgetary “grand bargain,” has led to discretionary accounts – defense as the largest – taking the brunt of deficit reduction efforts. This is true despite consensus within national security circles about the challenging nature of the security environment. As daunting as the future threat is, it’s the current (and projected) fiscal environment, the partisanship, and the seeming inability of national leaders to address these concerns, that are the biggest issues the military faces.

The 2011 Budget Control Act showed the Army the first effects of diametrically-opposed resource challenges. Given the continuing combat operations in the Middle East and new concerns over an irredentist Russia in Eastern Europe, the Army tried to preserve its force size as much as possible, using traditional force management adjustments to the big three “rheostats” of end strength, readiness, and modernization. It had to raid readiness accounts during the 2013 Sequestration and is now risking its modernization to stabilize end strength and to address readiness deficits. These measures are eminently sensible within a fiscal environment that promises relief in the near future; however, if austerity persists — as trend lines suggest it will –they will prove dangerous.

What of the new presidential administration’s plans to increase defense funding? President Trump clearly desires to rebuild the military; unfortunately, his budget plans fail to address the ongoing structural imbalance between spending and revenue. If enacted, his plans are likely to exacerbate these trends. In order to take pressure off of defense accounts, entitlement reform is necessary; but restructuring Medicare and/or Social Security is off the table. Even if the Administration wanted to restructure them, Democrats wouldn’t. Any budget increases that Mr. Trump gets will have to be financed through cuts to non-defense discretionary accounts (which Democrats will fight) or via deficit spending (which is an anathema to fiscal conservatives in the U.S. House of Representatives). While they may bring temporary relief, such budget increases will not be sustainable in the mid- to long-term.

This fact highlights a glaring need for new ways of thinking about resources within the Army. The traditional force management practice of playing end strength, readiness, and modernization off each other while awaiting the historical rebound in budget authority is not aligned with trends in the current or future environments. In fact, it is best to discard the rheostat model altogether because it focuses too much on current-year budgetary adjustments (among major appropriation types. As such, it is poorly-suited to sustained fiscal austerity; and, is an inappropriate basis for a long-term strategic resourcing culture. A more comprehensive framework is required.

Strategist John Collins articulated a useful approach in his book, Grand Strategy: Principles and Practices, proposing eight principles of preparedness to guide development of military readiness and capabilities during the uncertain, post-Cold War budget environment. Now, updated to reflect the modern day, the following principles provide a more comprehensive lens and properly focus on the Army as a system: roles and missions alignment; sufficiency; regional expertise; overmatch; interoperability; mobilization and sustainability; foresight; and will to be ready. When carefully considered, preparedness principles produce an integrated perspective that can greatly aid senior leaders in resource decision-making. Within this new paradigm, balance is essential, as significant risk can accrue when any of these principles are neglected.

How would holistic, systems-level considerations improve decision-making within the Army? After all, there are only so many resources, and priorities must be set. Looking at things from a different perspective isn’t going to change topline funding levels; however, approaching broader preparedness principles with an open mind, a willingness to question assumptions, and an inclination to embrace new approaches, can and will identify promising options. Importantly, leaders need to look both within and across the principles, and not individually examine components of each one. The true benefit to using preparedness principles (or any other system-level framework) is that it forces leaders to get out of their functional silos and consider more novel and integrated approaches. If done correctly, this holistic look will identify key factors and linkages, produce a more informed determination of opportunities and risks, and facilitate a broader range of potential solutions.

For example, the Army needs to address its modernization strategy, which currently violates the principle of foresight, Collins’ prescient warning against thinking in silos about readiness versus modernization. Applying foresight suggests that the Army’s current prioritization of unit readiness over future needs will leave the Army poorly-postured against the likely, and more dangerous, fights of the future. Current resource decision-making points towards accepting increasing risk, or, when the risk gets too uncomfortable, towards going back and gleaning resources from end strength and/or readiness accounts. However, this cyclical raiding of accounts is inefficient and counterproductive. It continues to violate foresight while simultaneously creating issues within other principles. This is not surprising. Linear cause and effect interventions within a complex, adaptive system invariably result in unwanted and/or unanticipated effects elsewhere in the system. A holistic look at the entire entity is required, to identify and influence the key factors and linkages that can best move it in the desired direction.

With that in mind, we can turn our attention to the principle of will to be ready. At the national level, this obviously points to adequate resourcing, but it goes much further than that. For the Army, this also entails a willingness to make a difficult but necessary change, one that aligns institutional processes and culture with both the needs of the force, and with the realities of the strategic environment. The Army recognizes that it has a strategy-to-resource mismatch and that solving it means doing things differently from now on. The question is, does the Army have the will to change how it manages resources?

Sustained austerity demands a new strategic culture, one that approaches decision-making through a preparedness lens, and that embraces both innovation and process reform.

There is a window of opportunity here, as the new Administration’s advisors, including the Secretary of Defense, have questioned traditional ways of doing business. New, more efficient approaches are likely welcome. The Army should take this chance to streamline its business processes and inculcate both cost-consciousness and innovative thinking into its DNA. This will require a clear and compelling vision, leadership by example, and incentives (or punishments) to force change, and to embed new cultural practices. Such change will be extremely hard for an organization as large and tradition-bound as the U.S. Army, but it is necessary, to ensure a viable land power capability now and into the future. That said, the will to be ready will be more effective in eliciting budgetary commitments when the congress can link immediate and important national security problems to the funds requested to meet them., or when money is applied to other clear national security gains, most notably interoperability and overmatch.

Optimizing interoperability to match the requirements of today’s strategic environment offers a significant opportunity. For example, to be more sustainable in the future, the Army needs to examine its active and reserve component mix. It will require frank, open discussion about relative strengths and weaknesses, and must dispense with the type of political infighting that reduces strategic options, and sometimes veers debate into the realm of the delusional. Both force components are critical to the Army’s future, but they are not the same. Balancing across them to find the right mix of capability, responsiveness, and affordability is paramount. If this is done right, and Army leaders from all components can maintain an enterprise view, it will relieve some of the pressure on other areas of preparedness (such as sufficiency) while still maintaining capacity and capability. For an army struggling with insufficient funds to meet stated requirements, budget analysis will tend to emphasize reserve components, since such forces (at least superficially) offer more “bang for the buck”. This demands a tailoring of the reserves’ missions, formation sizes, and training practices to produce a more efficient yet still capable force. Decision-makers should focus on better active and reserve component integration, such as having rotational reserve units at battalion level or lower, which can be plugged into the active force where needed. This would define their training requirements and be a potential force multiplier.

The Army must also continue to modernize the force. Some of this falls under the principle of overmatch, but modernization also should include process innovation. Existing law limits some approaches (without Congressional action), but recent legislation has given the Service Chiefs enhanced authorities within the acquisition system. These need to be tapped to bring about real change in process and outcomes. “Requirements creep” — defined as “the tendency of the user (or developer) to add to the original mission responsibilities and/or performance requirements for a system while it is still in development” — cost overruns, schedule delays, and cancelled programs are the face of Army acquisition today. Reforms should center on establishing realistic requirements and enforcing valid cost projections. To facilitate this, the Chief of Staff of the Army should strengthen oversight, hold people accountable, and consider shifting acquisition program benchmarks to a time-based, vice cost-based, metric. The Army should also aggressively exploit commercial-off-the-shelf technologies, particularly in the information technology and cyber realms, as a means to reduce development costs while enhancing capability. The Army is pursuing this in some areas, and the Better Buying Power 3.0 initiative encourages it, but the existing culture and process substantially reduce potential gains.

Sustained austerity demands a new strategic culture, one that approaches decision-making through a preparedness lens, and that embraces both innovation and process reform. Preparedness calls for — indeed requires — a holistic, systems-based approach to attaining, maintaining, and ensuring military capability now and in the future. Failure to adopt a new strategic culture in the face of clear political and fiscal trend lines entails significant risk, and will likely result in a less capable, less prepared force in the future.

Muddy Waters is Assistant Professor of Defense Management at the U.S. Army War College and a retired U.S. Navy officer. The views in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army or U.S. Government.

Illustration: Congressional Budget Office