Sir Michael Eliot Howard OM CH CBE MC FBA FRHistS, In Memoriam

To say that the fields of war studies and military history would not exist as we know them today without the contributions of Sir Michael Howard would be true, but it does not do justice to the man as a scholar or mentor. While other venues have published more traditional obituaries and reminiscences, the WAR ROOM editorial team reached out to some of those influenced by Sir Michael Howard, personally and professionally, to share a bit more about his influence on their work and their teaching.

Jonathan Boff

Jonathan Boff is a Senior Lecturer in History and War Studies at the University of Birmingham (U.K.).

Captain Professor Sir Michael Howard was the most important historian of warfare of the last hundred years, not least because he was the kindest and most generous of mentors to generations of military historians, including myself. He was also a brilliant lecturer. He was a natural showman in love with greasepaint and the roar of the crowd. I remember him, well into his eighties, holding forth for over an hour to a packed room at King’s College London on the study of war.

He hardly seemed to draw breath, and certainly never consulted a note. Rigidly upright in pinstriped suit and Garrick Club tie, his accent a mix of Wellington and the Brigade of Guards, English genthood personified, only once did he show signs of human frailty.

About half way though, he confessed to being thirsty. The chairman passed him a plastic bottle of water. Bertie Wooster looked on his aunts with less suspicion than Michael directed at this bottle. ‘It’s very hard to drink with elegance from a bottle like this…’ he began. With infinite slowness, be unscrewed the cap, raised it to his lips and sipped. A pause, of which Harold Pinter would have been proud, ensued. The audience, spellbound, held its breath‘… But I’ve just shown you how.’

Geoffrey Wawro

Geoffrey Wawro is Professor of Military History at the University of North Texas, and Director of the UNT Military History Center.

I got to know Sir Michael as a graduate student at Yale. He arrived when I was in Europe doing dissertation research and in those days, one wrote progress reports in the form of letters that took days or weeks to make their back and forth across the Atlantic. Michael was a helpful interlocutor while abroad, and when I returned to Yale to write up, he was wonderful mentor. He read chapter drafts carefully, annotated them copiously, and participated actively in roundtables to discuss research. He insisted that grad students working in germane areas lecture to his Modern Warfare course. Above all, Michael was a kind and decent man. Most of us grad students subsisted on meager diets, and I’ll always remember the Sunday lunches with roast beef and Yorkshire pudding that Michael and his partner Mark James would occasionally serve to a small group of military historians. After Yale, Michael and I stayed in touch and became friends, and corresponded regularly on matters great and small. Indeed, I dedicated my latest book to him, just a year before his death. Michael stands out as a man who took a subject of immense importance—military history—and made it respectable and relevant, by his writing, his teaching, and his powers of team-building and organization. He was truly one of the greats and we will miss him dearly.

Conrad Crane

Con Crane is a military historian with the Army Heritage and Education Center.

When I was researching for my Ph.D. dissertation and first book examining the legacy of WWII strategic bombing that really made any decision to use the A-Bomb moot, I found Michael Howard’s writings about the terrible choices facing strategic leaders in existential wars very enlightening. He noted, “Those responsible for the conduct of state affairs see their first duty as being to ensure that their state survives; that it retains its power to protect its members and provide for them the conditions of a good life.” Accordingly, when statesmen and their generals deal with the ethical issues of a war threatening their people and nation, “the options open to them are likely to be far more limited than is generally realized.” For the Allied leaders in WWII, the ultimate moral failing would have been to lose that conflict.

Tami Davis Biddle

Tami Davis Biddle is Professor of National Security Affairs at the U.S. Army War College.

Sir Michael Howard was a remarkable scholar, writer, and teacher. He was also a deeply wise and generous human being. My direct interaction with him was limited, but he nonetheless left an indelible impression on me in the early phases of my professional career. Every word of encouragement and praise he offered was more precious to me than gold. I truly believe that every person who has worked in the field of military history since the 1960s has been profoundly influenced by Sir Michael’s scholarship. As members of a discipline and cohort we have sought, in our own ways, to aspire to the stellar example he set. We will miss him terribly, but we will remember him always and take great inspiration from his example.

William Philpott

William Philpott is Professor of the History of Warfare in the Department of War Studies, King’s College London and President of the British Commission for Military History.

Sir Michael Howard only published one short volume on the First World War, The First World War (Oxford, 2002; republished as The First World War: A Very Short Introduction in 2007) but his understanding of that conflict was immense. In nominating it as one of the five best books on the war for the Wall Street Journal in the war’s centenary year, perhaps I was acknowledging a debt of gratitude. I had the good fortune to be taught by him as a final-year undergraduate shortly before his retirement from Oxford University, where he convened a paper British Strategic Planning and the Dardanelles Campaign. Through this class I discovered the First World War and explored its strategic context.

Michael Howard went out of his way to engage his students’ minds and add value to their studies. In addition to convening seminars for the examined paper he organised a supporting series of guest lectures; the highlight, for an impressionable undergraduate, being the vivid recounting by a Field Marshal now in his late 80s of his experiences as a young lieutenant at the Dardanelles. This class and its inspirational teacher directed me onto the scholarly path I subsequently followed; and, more practically, Sir Michael supported my application for doctoral studies at Oxford. Although his class did demonstrate to me that British strategy became all about the western front, on which my own scholarship has focused, and that the Dardanelles was but a ‘sideshow,’ the last manifestation of the imperial and maritime British strategic paradigm that fell away during the twentieth century, as ably explained in his published Ford Lectures, The Continental Commitment: The Dilemma of British Defence Policy in the Era of the Two World Wars (Temple Smith, 1971). My first book, Anglo-French Relations and Strategy on the Western Front: Independence or Alliance, 1914–1918 (Palgrave Macmillan, 1996), based on my doctorate, explained how that dilemma played out in the strategic conduct of the British army’s principal campaign of the war.

I was unlucky not to have Michael Howard as my doctoral supervisor, although as retirement and the US beckoned he was no longer taking on research students. Nonetheless, he took and took a kind interest in the development of my career thereafter, we met intermittently, and we had opportunities to work together, especially after I joined the department which he founded. Over the years my scholarly interests diversified from British to French strategy and from the high command to the battlefield. When I published my study of the 1916 Somme offensive, Bloody Victory: The Sacrifice on the Somme (Little Brown, 2009), its approach owed much to Michael Howard’s philosophy of viewing military events in the round, explaining the political and social context and consequences of battle as well as the fighting. Michael reviewed the book kindly in the Times Literary Supplement, but also took the time and trouble to write to me personally. I cherish his sentiments that it was ‘exactly the kind of book I would have liked to write myself…I feel vicariously proud of you’.

Above all, Michael Howard was able to put the first world war in context, explaining it a just one war along a continuum from the dawn of the industrial era: a manifestation of mechanical war’s grisly reality (which Howard himself had experienced), a challenge and trauma to societies, but by no means an exception. Such an understanding has informed my own scholarship and teaching, so much so that my class handout starts with the quotation: ‘That the Great War’s course should have been so terrible, and its consequences so catastrophic, was the result not so much of its global scale as of a combination of military technology and the culture of the peoples who fought it.’ A huge piece of history captured in the precise, balanced language of a master historian.

The views expressed in this memoriam are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

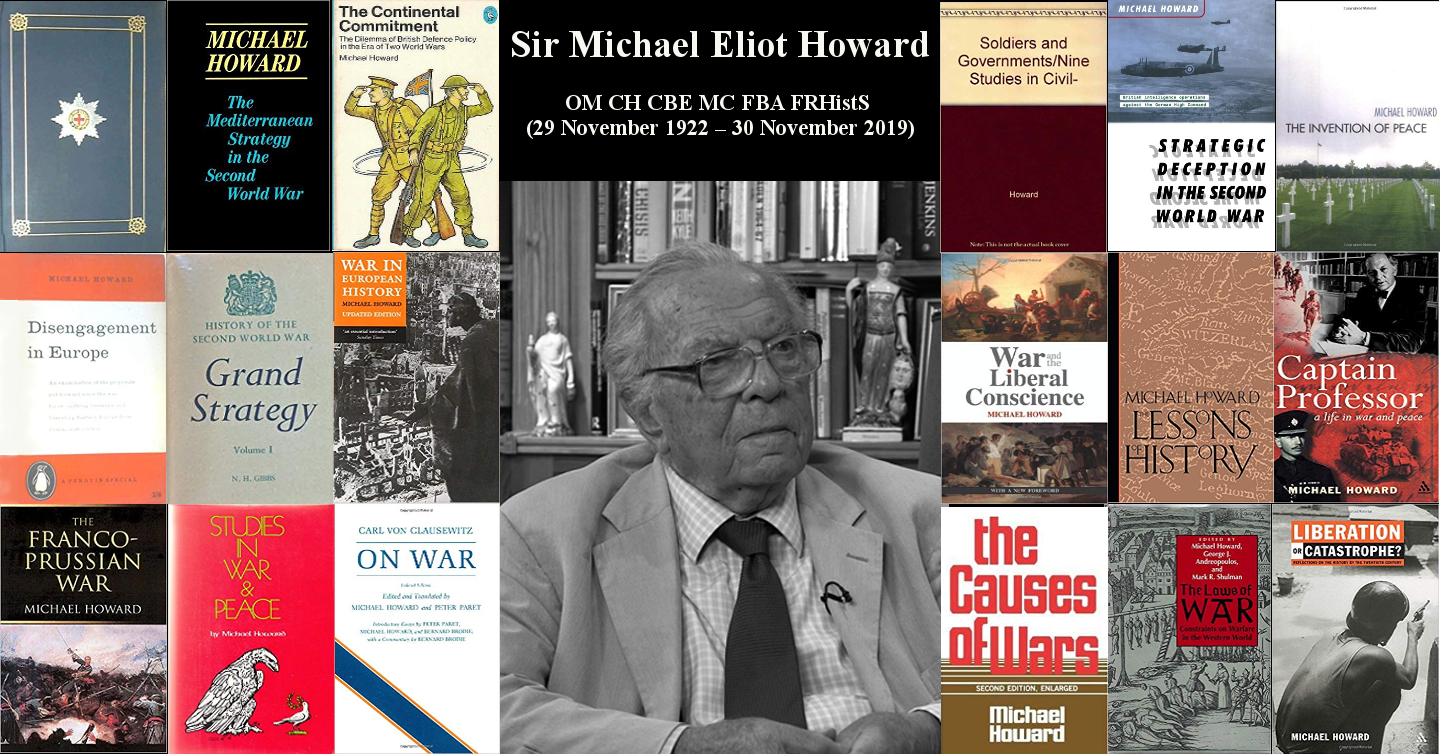

Photo Description: Sir Michael Howard surrounded by some of his most well known works.

Photo Credit: Library of Congress (Center photo)