In Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, characters who increase in wisdom are those who ascend from the cave’s darkness (ignorance, crudeness) to the surface’s daylight (knowledge, sophistication).

In early 2018, 13 small drones armed with explosives swarmed the Russian-occupied Hmiemim airbase in Syria. Russian forces accused the United States of launching the attack, citing the unmanned aerial vehicles’ (UAV) precision and synchronization as evidence that they were high-tech, despite their primitive appearance. Former Marine Rob Lee, a doctoral candidate now focused on Russian defense policy, dismissed that claim with, “sometimes it is easier just to blame the Americans than acknowledge that [the Russians] were not prepared to stop unsophisticated, off-the-shelf UAVs.” Indeed, terrorist drones frequently pelt state-occupied strongholds in Syria, sometimes with success. After a drone attack at the same airbase damaged seven military aircraft, Russia admitted that it was the work of a high-functioning rebel drone.

Several months and several attacks later, the Russian Army uncovered a drone workshop inside a cave system nearby. Amid paltry rations and a blood-stained prison block, rebels manufactured and modified consumer drones that partially simulated American sophistication. The surging commercial UAV industry has granted terrorists sudden and broad access to simple and affordable, yet effective airpower. Accustomed to having to deflect brute state force with indirect combat, terrorists have found a new offensive edge in drones. Rather than combating few exquisite platforms in the aerial domain, states must now contend with a much broader range of actors exploiting airpower.

As a result, the offense-defense dialectic—the alternating rhythm of combat innovations between enemies—risks tilting in favor of terrorists. On the offensive side, commercial drones boost terrorists at all levels of conflict. Strategically, they facilitate striking propaganda used to recruit support and draw resources. Operationally, simple drones deliver context-specific and time-sensitive intelligence for both planning and real-time combat. Tactically, they extend terrorists’ reach and lethality, yet at lower risk to operators.

On the defensive side, terrorist drones threaten tactical air control, usually challenging air parity. For instance, General Raymond Thomas remarked in 2016 that his past year’s “most daunting problem was an adaptive enemy who, for a time, enjoyed tactical superiority in the airspace under our conventional air superiority in the form of commercially available drones.” More concerning than air-to-air contests are terrorist tactics that can win them an upper hand against ground forces lacking air support, whether those of special forces or of weak states thin on aerial resources. Exquisite airpower is scarce, but civilian drones are not. Under these conditions, terrorists might enjoy stints of even air superiority.

In Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, characters who increase in wisdom are those who ascend from the cave’s darkness (ignorance, crudeness) to the surface’s daylight (knowledge, sophistication). When this process is gradual, transitioning from backlit flickers to beholding dull flames, to a stepwise climb from the cave, the adjustment is more manageable. Access to innovation has launched the terrorists topside, helping them to take to the skies faster than expected. Instead of dilating complex technical and infrastructural capacity over time, commercial drones, packaged with inbuilt sophistication, have allowed them to skip steps on the way up with little effort or discomfort. In fact, it seems to be states that are most pained by the sunlit sky as they watch resource-constrained rebels pose an aerial challenge with “kids’ toys,” as David Hambling of Wired calls them, in his article “Toy Planes, Real Threat.” Going from being mostly grounded to effectively fielding an air force is a giant leap in terrorist capabilities. Going from being mostly a rich nation’s air game to admitting a broad spectrum of violent nonstate players is a tremendous expansion of activity. Thus, the aerial domain is rapidly changing in its quality of technology and quantity of users.

Violent nonstate actors’ use of drones is barreling forward because the commercial drone industry is. Booming in sales, sophistication, and expansion, commercial platforms lower the threshold to enter the aerial domain yet deliver high functionality. Initial concerns about proliferation focused on the spread of military-grade technology—scavenged or sponsored Predators, Reapers, and Watchkeepers being turned on their suppliers. Given such platforms’ expenses, restrictions, and technical complexities, such fears have not widely surfaced. In fact, despite possessing military-grade drones for two decades (compliments of Iran), Hezbollah sports an unimpressive record of use. It has been slow and incremental, and each attempt has been interdicted by Israeli forces. Although it’s the first known terrorist group to successfully launch a drone (2004), to successfully weaponize a drone (2006), and to cause casualties with an armed drone (2014), Hezbollah accounts for only 3% of the incidents in our dataset on violent nonstate actor drone uses. The reason is that they relied on military-grade drones.

The military echelon of airpower is scarce for its high costs, making weaker actors who possess it averse to risking it against powerful nations. Instead, terrorist drone proliferation correlates with the progress of expendable toy quadcopters and model airplanes. Consumer models are inexpensive, widely available, and user-friendly, featuring supply-side traits opposite those of costly, proprietary military drones. Furthermore, the commercial industry is delivering more and more functionality and autonomy as it hustles to meet consumer demand in multiple industries.

Commercial platforms are certainly less advanced than military-grade models, but they tend to do the trick. Since terrorists are not concerned with norms and laws of conflict (e.g., discrimination, proportionality), they do not require norm-enabling drones. For instance, a commercial UAV generally cannot persist over a target long enough to confirm identity and await a moment of minimal collateral damage to conduct a precision strike. A commercial UAV can, however, persist long enough to make it over a hill and indiscriminately drop a makeshift munition onto a target. In short, they are sufficient for terrorists’ tasks. That some urge smaller and even advanced militaries to use commercial drones for lower end tasks demonstrates their draw. That groups like Hezbollah and Hamas prefer commercial over military models for some missions, despite having access to both, reinforces their attractiveness.

It is occurring in hot and cold war theaters. Terrorists are using drones against strong and weak states. They are using them in urban, rural and tribal settings.

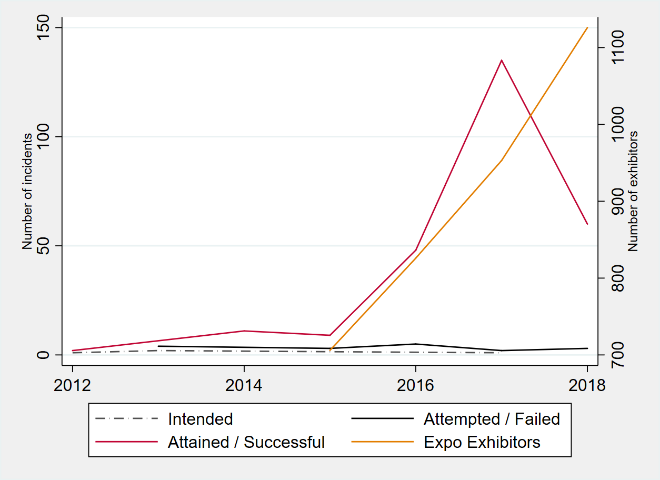

What this means is that the militant drone threat is likely to continue advancing at the pace of the civilian drone market. In other words, fast. We compared our data on terrorist drone uses with some measures for drone market growth. As more exhibitors enter the market (Figure 1), terrorists attain more success. Using another measure of industry advancement, progress in consumer drone ranges (not reported here), we find a nearly identical trend. Just as peaceable nonstate actors are taking advantage of this capability, so are violent ones.

Figure 1. Terrorist drone outcomes alongside a count of exhibitors featured in selected annual drone expos, 2012-2018. The airshows—AUVSI Xponential, the Commercial UAV Expo, Drone Days Belgium, and the International Drone Expo—were selected for their temporal stability, wide geographic coverage, variation in size and exclusivity, and international standing. Due to the irregularity of source reporting, we count each discrete incident as 1 even if multiple drones (i.e., 70 over 24 hours) were used. (The drop in the count of terrorist drone successes in 2018 is a function of the concentrated 2017 US campaign against Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant, a prolific drone user, that significantly degraded its operations.)

Nonstate actors’ commercial drone use is not constricted to the Hmiemim airbase or even to the Syrian civil war. It is occurring on every continent except Antarctica. It is occurring in hot and cold war theaters. Terrorists are using drones against strong and weak states. They are using them in urban, rural and tribal settings. Insurgents use drones for a variety of reasons: advancing against despotic governments; evading the same; supporting activism and separatism (like this $1B explosion of Ukrainian ammo); ambushing targets (like this swarm on an FBI hostage raid); assassinating opponents (like this attempt on the life of the Venezuelan president); smuggling (into prisons and elsewhere), committing narco-crimes (like with these cartels); and also in jihadism, attrition, provocation, spoiling peace talks, and more. Islamic State alone uses them for propaganda generation; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; target acquisition; command and control; weaponized attacks; and even for advanced experimentation with chemical weapons.

Still, the Syria story maintains pride of place. It features the first lethal drone attack by a violent nonstate actor, the first terrorist-on-terrorist drone warfare, and the most drone-dense conflict in history. One catalog counts at least 32 identifiable military, commercial, consumer, and homemade models flying on all sides of the fight.

In this context, the drone workshop cave is a powerful symbol of terrorist drone use at large. Commercial UAV advancements are fast and far-reaching. Consequently, the number of violent nonstate actors emerging from their real caves to take to the skies with alacrity is jolting militaries. The offense-defense dialectic is shifting with potentially strategic effects, and asymmetric battlefields are changing. To meet these challenges, we recommend three types of responses and one caution.

Our first recommendation applies to states. We urge thoughtful regulation on the sale and exportation of private sector drones. Admittedly, terrorists are attracted to commercial drones because it is so difficult to regulate them, making them easily accessible. Imposing regulations risks pushing manufacturers toward capital flight, reducing the flow of funds within a nation’s economy. Regulations are the most strategic solution, however, to raise a boundary against terrorist drone access and use. Structural solutions are more robust than those that depend on individual agency. Eliminating access to drones is more primary than mitigating the many effects of deployed drones. Each state must choose to strike the political, legal, and economic balance of regulation that befits its domestic context.

The second and third suggestions apply to security providers. The first frontline response must be technological. The proliferation of small, simple drones calls for the proliferation of small counter-drone mechanisms. Several anti-drone technologies already exist, such as the DroneGun or DroneCatcher, but the variety of offensive terrorist drone use calls for a greater variety of defensive options. Some should be constant and omnidirectional (such as at airports), others temporary and targeted. Some can be semi-permanent to a location; others must be highly mobile. Some should be optimized for obstructed or dense operating environments, such as urban or forested areas, while others should feature longer ranges across open terrain.

The second type of response we promote is counter-drone training and protocols for military, law enforcement, and other security personnel. To be effective, appropriate counter-drone platforms must be well assimilated into a given fighting force, confidently and consistently employed across contingencies and in coordination with other systems.

Our caution is that both technological and training solutions must be cost-proportionate and sustainable. Civilian drones are inexpensive, even disposable, relative to other light weapons and ammunition. It is neither proportionate nor sustainable to employ traditional airpower or weaponry, such as fighter jets and Patriot missiles, against rebel-operated commercial drones. Neither should military-grade drones be used against them, as these are not designed for air-to-air combat. This implies that it will likely be the boots on the ground, not airmen, who will bear the brunt of defense against terrorist drones.

Many security experts have been aware of and preparing for terrorist aerial threats for decades. The expectation, though, was that they would continue to scrounge, tinker, and hijack with incremental improvements. For most of the airpower era, state powers have easily kept in stride. Commercial drone innovations have swiftly launched these threats forward in number and sophistication. Impoverished rebels, in figurative and literal caves, are now able to strafe targets with swarming, lethal airpower. States of all strengths must adjust to the many new glints in the sky.

Kerry Chávez is a PhD candidate in Political Science at Texas Tech University, focusing on strategies and technologies of conflict. Her research has been published in the Journal of Conflict Resolution, Social Science Quarterly, and PS: Political Science & Politics.

Ori Swed is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Social Work and Director of the Peace, War, & Social Conflict Laboratory at Texas Tech University. His scholarship on nonstate actors in conflict settings and technology and society has been featured in multiple peer-reviewed journals and his own edited volume. He also gained 12 years of field experience in security, counterterrorism, and intelligence during combat roles in the IDF, as a special forces operative and reserve captain, and a former private security contractor.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Though larger and more expensive than the expendable models that have been employed by terrorists so far, these hexacopters shown are modified for air monitoring but are easily adapted to other payloads.

Photo Credit: Original Image by LoggaWiggler from Pixabay