With such overwhelming numbers, how could the Allies not win?

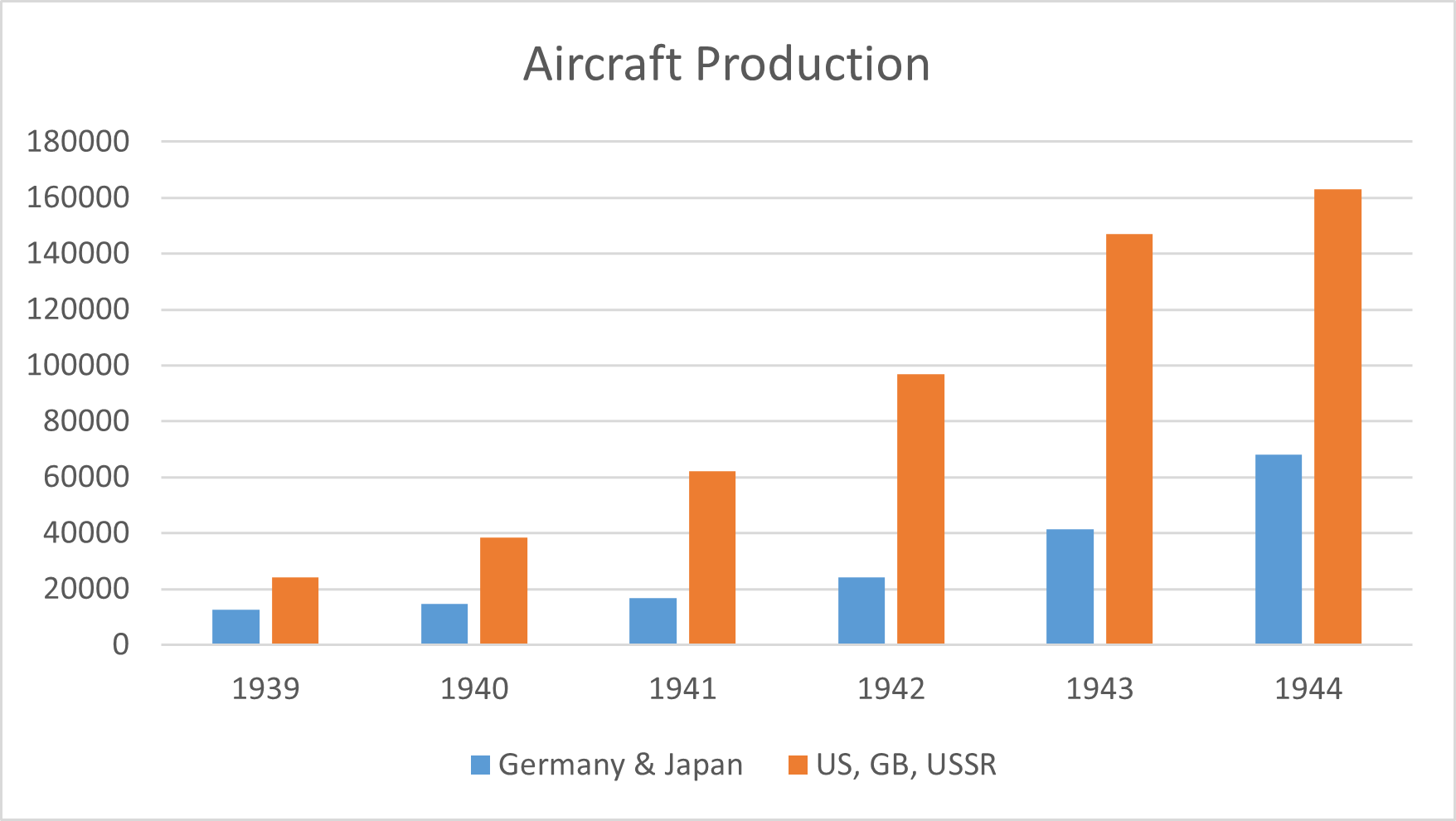

The numbers in World War II are striking. The Allies, who in many ways had not prepared properly for conflict, produced just over 20,000 aircraft in 1939, a number already almost double that of Germany and Japan. By 1943, the Allies manufactured about three and a half times more airplanes than Germany and Japan.

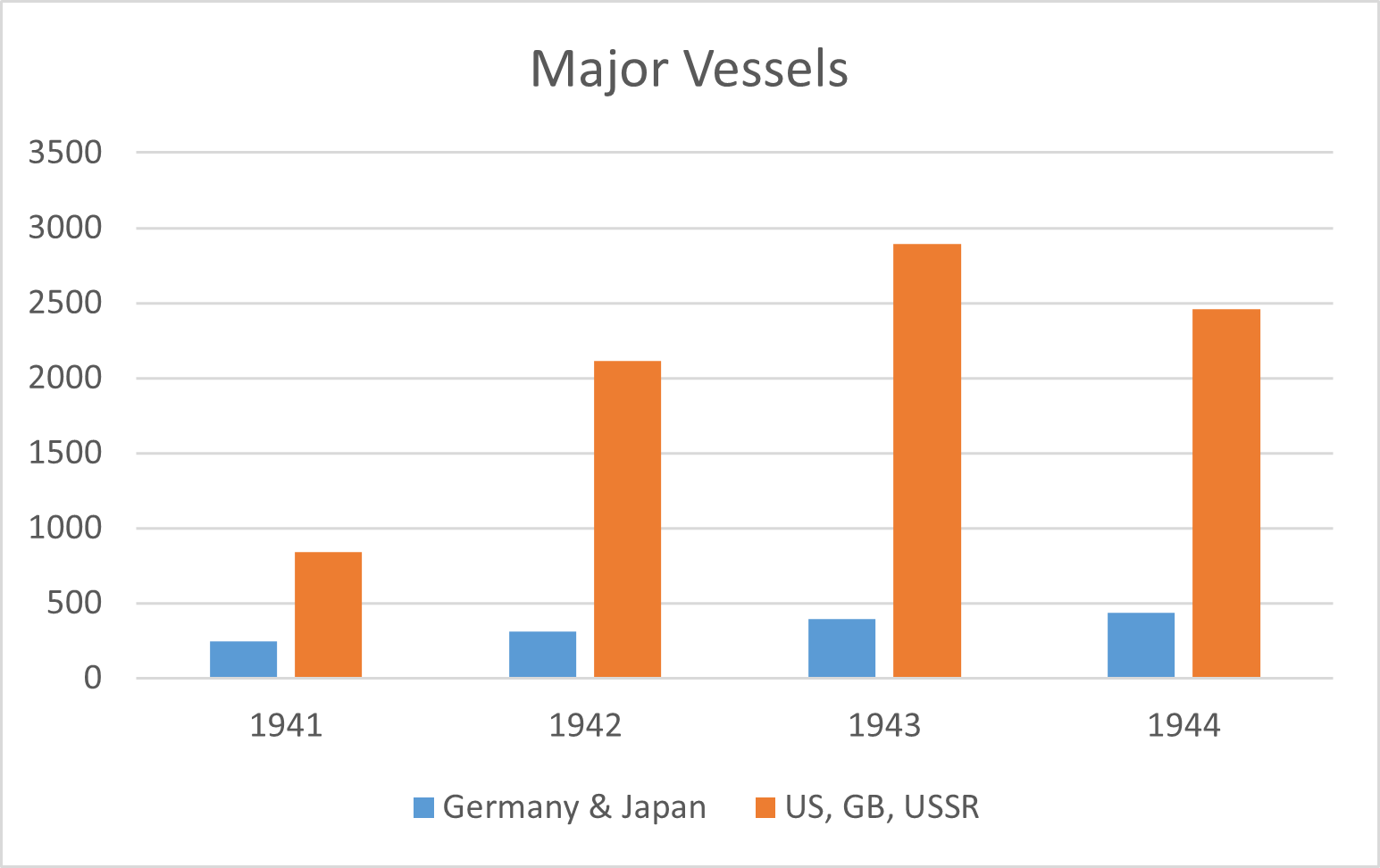

The ship building numbers overwhelm the eye even more. In 1943, the Allies—led by the United States—produced seven times the number of ships that Germany and Japan did, even including German U-boats.

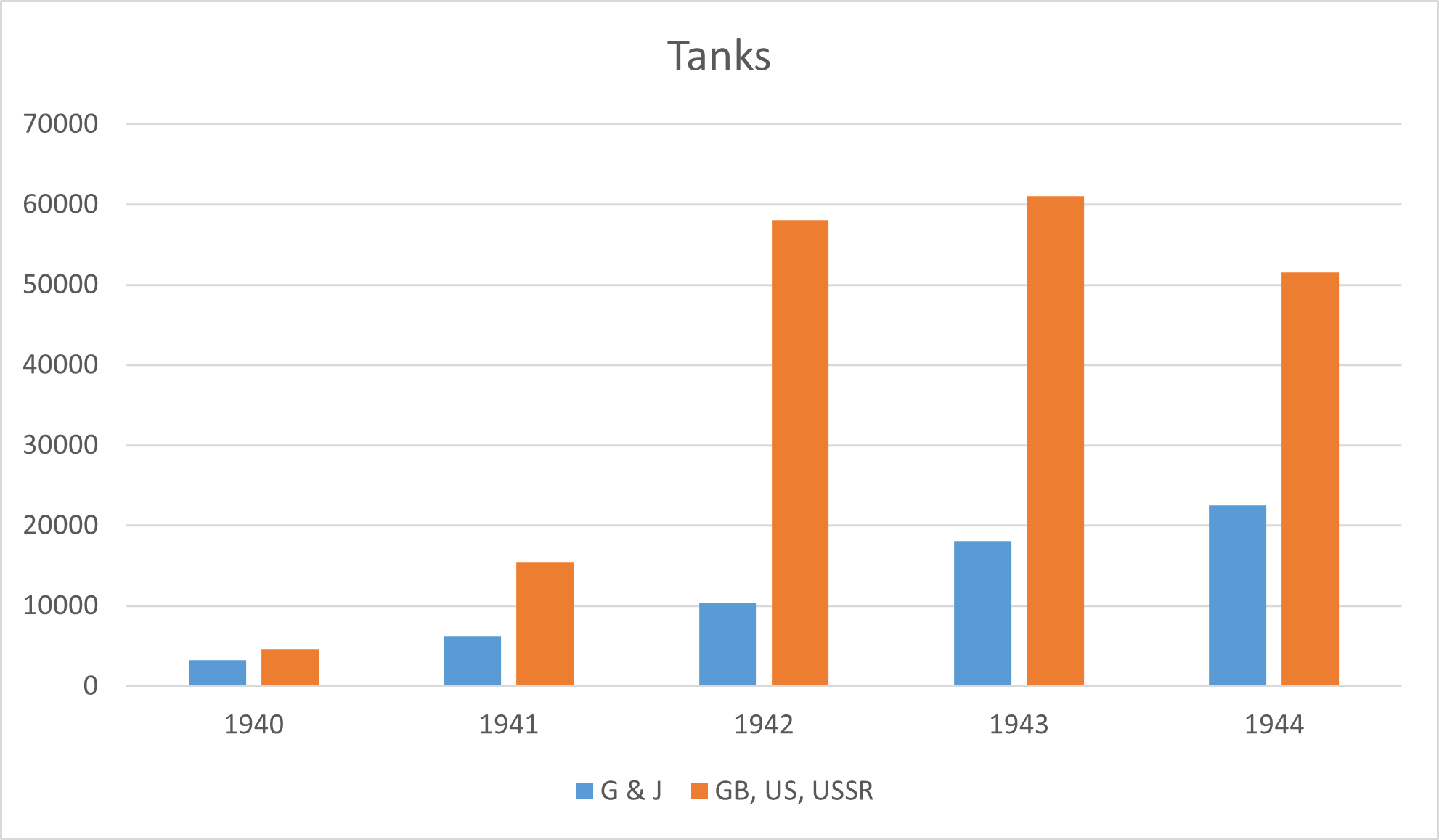

As a continental power, perhaps Germany did not need to produce so many ships, but the disparity in Allied and Axis production rates of tanks was just as impressive. Again, in 1943, Germany and Japan produced less than 20,000 tanks while the Allies manufactured more than 60,000.

With such overwhelming numbers, how could the Allies not win?

War is never so simple. Despite the Allies’ vast production capabilities, historian Richard Overy refused to accept their inevitable victory in World War II in Why the Allies Won, first published in 1995. Pushing back in the tradition of the best historians against foregone conclusions, he wrote regarding many battles that the “margin of victory or defeat was often so slender that general theories look out of place.” He continued by explaining, “Battles are not pre-ordained. If they were, no one would bother to fight them.” Indeed, he went so far as to write that “no rational [person] in early 1942 would have guessed at the eventual outcome” of the war.

As such, Overy wanted to challenge the widely accepted idea that the Allies won because they had a significant material advantage. Overy showed ebbs and flows in regard to which side possessed advantages in resources. He also stressed the ability of both the United States and the Soviet Union to mobilize at almost lightning speed. Although the US and the Soviet Union took very different paths toward mobilization, their experiences stood in contrast to Germany’s failure to make the most of its resources.

While Overy took a wide-ranging approach to the war overall, his three central questions highlighted his largely material approach 1) how did the Soviet Union “recover its industrial resilience” after dramatic losses to the Germans, 2) how did the United States become a “military super-power” in less than a year when other nations required much more time and 3) why did Germany struggle to produce mass quantities given all the resources at its disposal? However, because most of those questions are answered chronologically about halfway or so through the war, Overy began the work with a chapter on naval warfare to highlight the war’s prosecution, to include allowing the Allies the “luxury of picking easier fields of combat.” The reader observes relatively quickly, moreover, that he intends naval warfare to encompass the domains of both sea and air because command of the sea required command of the air. As Overy put it, “air power worked its transforming art in the Atlantic as it had done in the Pacific and the Mediterranean.” Regarding the Battle of the Atlantic in particular, Overy explained that because the victory seemed so sudden in the early summer of 1943, some may assume “some special factor, lately introduced into the battle, explained its abrupt conclusion.” As such, Overy stressed that the outcome required, for example, more than simply introducing long-range aircraft to close the gap that German submarines had been exploiting, although of course these aircraft equipped with improved radars did help. Rather, he placed the emphasis on “months of patient, painstaking labor” that paid out dividends while tactics and technology improved. This point may be the closest Overy came to a thesis as he contended that “[t]actical and technical innovation won the war at sea before sheer numbers came to matter.” While this sentence applies in this context to the “war at sea,” he also reiterated throughout the book that the Allies learned relatively quickly in combat and in other domains as well, although he did not detail how this process occurred. The Allies innovated and learned just quickly enough to allow for time to produce material in overwhelming quantities, the subject of his three “critical” questions.

Still, even learning had its limits. For those looking for decisive battles in World War II, Overy argued that the Allies won many battles by slim advantages. Midway, for example, was “won by the narrowest of margins—ten bombs in ten minutes.” This emphasis reinforces his insistence that no one could predict the war’s conclusion. Similarly, he deemphasized the role of intelligence, dismissing those who have stressed its importance as seeking to be “fashionable” at the expense of giving it an outsized role. This approach accords with his overarching tendency to avoid stressing simplistic war-winning advantages.

For Overy, the weapons that both sides entered the war with contributed the most to its outcome, as German attempts to develop an asymmetric advantage through rockets, jet aircraft, and other similar programs came to naught. Overy insisted that improved technology could make contributions, but that they themselves did not explain victory. Indeed, the “core armoury of offensive warfare …consisted of aircraft, tanks and trucks.” In other words, just as he stressed tedious organization and logistics, so too he emphasized less glamorous but essential technology that could be organized effectively. The only hope for the Axis nations would have been to develop “entirely new weapons,” namely the atomic bomb, which would have been difficult even in Germany due to numerous reasons. Still, Overy did not claim that atomic weapons won the war even for the Allies.

Axis nations also did not properly stress administration, logistics, and organization because of their more martial military cultures.

Similarly, Overy consistently stressed the extent to which attrition characterized warfare in multiple domains. Attrition has become a bad word for understandable reasons, not only for its connection to the senseless loss of life during World War I, but also for how many believe it became the problematic essence of American strategy in Vietnam, although that is up for debate. It is also worth considering in light of recent military operations between Armenia and Azerbaijan, with some commentators stressing how attrition quickly became a fall-back strategy.

In terms of his coverage of warfare, Overy’s survey can be considered somewhat conventional in stressing many of the best-known battles. For land warfare, for example, he begins on the eastern front, which he argued has been largely accepted as the key front in the war, then jumps to Normandy. Overy might argue that his interest in seeking to understand how the war was won rather than how it was fought dictates this decision. But this distinction seems somewhat thin, albeit perhaps necessary as the only way to cover as much as he does in less than 400 pages.

In the work’s second half, Overy largely leaves the battlefield behind to focus on the forces enabling the battlefield, both material and moral. Citing the initial importance of the leadership of Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin, for example, Overy noted some important change over time in areas that do not always receive much attention in military history, particularly administration. He pointed out that the “war was not so much led as administered” (269), and this capability provided the Allies with an important advantage as Germany lacked administrative unity to see the war holistically. Axis nations also did not properly stress administration, logistics, and organization because of their more martial military cultures. Those cultures meant Germans and Japanese prepared their militaries to focus on the fighting of battles and campaigns, not the managing of overall war efforts, which has current relevance in light of the US military’s recent embrace of lethality and a warrior culture. In Japan and Germany, he contended, it would have been “inconceivable that a Marshall or an Eisenhower, with no combat experience between them could have won supreme command.” It is in such areas that Overy brings in important non-material and non-kinetic and more organizational factors to the forefront for consideration.

The book’s last chapter stresses moral factors almost exclusively. If there is a bright spot in this book, it is Overy’s contention that good wins, in part by providing a genuine boost to morale. Prior to the war, democracy had been “in retreat everywhere;” but right was on the side of the Allies and worked as an intangible advantage. These moral arguments are problematic at points. The good-bad binaries can be too simplistic. For example, Overy pointed out at the beginning of the work that the war made “the world safe for communism,” which was hardly a positive outcome. And while the evils of the Nazis stunned the world, his argument that German immorality weakened their own efforts—such as by horrifying many officers who had served on the Eastern Front—perpetuates the idea of a German Army opposed to Nazism, which many historians have debunked. .

Why the Allies Won is not the final word on World War II, and it has not gone unanswered. For example, after reading Overy, consider tackling Phillips O’Brien’s How the War Was Won next. Although both stress the importance of the air and sea domains, O’Brien pushes back at Overy’s contention regarding the eastern front’s decisiveness; indeed, he largely challenges the importance of land warfare to the war’s outcome. Another key difference is how O’Brien highlights the spaces between the battlefield and the homefront as key battlegrounds in preventing people and material from getting to the battlefield in the first place.

Yet both emphasize the centrality of a nation’s ability to produce massive amounts of material and numbers of platforms, even if they both recognize that this does not necessarily ensure victory. Given the intriguing questions that Overy raises in this work and the historical perspective he offers, it is clear that there are no simple solutions or easy answers for waging great power conflict, even for a nation bringing an outsized advantage in mass to the table. But that is the beauty of the work: it brings together what we think we know about this conflict into perspective, helping the United States to consider the extent to which it has a proper balance of material and moral factors given how patient, tedious organization and ordinary equipment in vast quantities helps to explain a war of such staggering scale and scope that it remains difficult to make sense of to this day.

Heather Venable is an associate professor of military and security studies at the U.S. Air Command and Staff College and teaches in the Department of Airpower. She also is the author of How the Few Became the Proud: Crafting the Marine Corps Mystique, 1874-1918. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, the Air Command and Staff College, the U.S. Air Force or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Left to right: Front row: Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur W Tedder, Deputy Supreme Commander, Expeditionary Force; General Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Commander, Expeditionary Force; General Sir Bernard Montgomery, Commander in Chief, 21st Army Group. Back row: Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, Commander in Chief, US 1st Army; Admiral Sir Bertram H Ramsay, Allied Naval Commander in Chief, Expeditionary Force; Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory, Allied Air Commander in Chief, Expeditionary Force; and Lieutenant General Walter Bedell Smith, Chief of Staff to Eisenhower.

Photo Credit: British official photographer, Imperial War Museum TR 1631

Other releases in the “Dusty Shelves” series:

- KOREA ON THE BRINK: GENERAL JOHN WICKHAM AND POLITICO-MILITARY CRISIS MANAGEMENT

(DUSTY SHELVES) - FIGHTING BY MINUTES, THIRTY YEARS LATER

(DUSTY SHELVES) - THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER (1988): THE FORGOTTEN PRIMER ON LEADERSHIP

(DUSTY SHELVES) - RIDGWAY’S KOREAN WAR

(DUSTY SHELVES) - ALL WAR IS LOCAL: ANTHONY QUAYLE’S EIGHT HOURS FROM ENGLAND

- POST-WAR TRUTH TELLING: THE WAR MANAGERS

- DYE: EXALTING THE TAIL OF THE AIRPOWER TOOTH

(DUSTY SHELVES) - PEACE FORMS: LOOKING BACK TO THE FUTURE OF WAR AND ANTI-WAR

- SHERMAN: THE OUTLIER OF INTERWAR “ATLANTIC” AIR THEORY?

(DUSTY SHELVES) - STRUGGLING TO SEE THE FUTURE: UNLESS PEACE COMES

(DUSTY SHELVES)