U.S. Army strategic leaders must be ‘War Winners,’ not ‘War Managers.’

The responses to our first Whiteboard were overwhelming! Thank you to everyone who submitted. We received a large number of strong responses.

The second Whiteboard launches 20 July, and we will be running these exercises regularly. Stay tuned.

Based on the judgment of the editorial board, the following (in no particular order) were the best responses to the following question:

How good is the U.S. Army at developing strategic leaders? Give the organization a grade (from F to A+), and support your assessment.

1. Russ Vane, Technical Advisor at the Department of Homeland Security and Student of the U.S. Army War College distance education class of 2019

GRADE: C-

Army strategic leader development will lag until it develops a culture of constructive contrarians. These are not threat mongers – “the low probability, high impact” crew. Instead, similar to “devil’s advocates” (but better), officers need to take the role of ferreting out the uncertainties of situations and evaluating creative, competing strategies. The role of constructive contrarian is an assigned staff role (maybe to J8). The constructive contrarian is doing the hard work of sensitizing the strategic leader to the known-unknowns. This can be expanded into Army reporting mechanisms where risk is computed. It also develops the introspective thought processes that are ultimately desirable.

Humans are prone to numerous cognitive errors, some of which can be mitigated by developing a culture that promotes finding the rough edges of strategies and anticipating pivots to rapidly exploit new information in changing situations. This may mean requiring every strategy to have its nemesis discussed in any planning process.

The problem may even start with a culture that rushes to judgment, as evidenced by the rubrics used to assess written coursework in U.S. Army War College. Generations of aspiring strategic leaders are told, “General Officers don’t have time to understand one’s uncertainty and the ramifications of alternatives.” This dictum may make students’ papers easier to grade but misses the benefits of having constructive contrarians. Taking the other side of any argument and presenting it forcefully is just the same thing as supporting a single argument.

2. Colonel Brian Cook (U.S. Army), U.S. Army War College Faculty

GRADE: D

The system has to account for risk.

We live in an era when our strategic leaders must compete just below the threshold of armed conflict in a Trans-Regional All-domain Multi-functional (TRAM) environment. To gain and maintain our strategic advantage, we must breed leaders comfortable taking and accepting risks in this environment. In our current leader development system, one mistake or failure by leaders can quickly rob the Army of an extremely talented officer. I know many skilled and talented officers who will not gain another rank due to this antiquated approach and accompanying human resources management system that rewards conformity and risk aversion. Granted, we have programs and processes such as the Army Board for Correction of Military Records to reconcile these errors. But they’re extremely laborious and time-consuming. Thus, officers who receive a mediocre performance assessment in one job rarely regain their position alongside their peers in the competition for promotion and selection. Every great officer in my career taught (or re-taught) me to underwrite the risk of my subordinate leaders. The problem is those leaders are the exception, not the majority.

Until we create or significantly modify our leader development and human resource systems to favor (or at least not punish indefinitely) the officers whom take and accept risk, we’re only going to get a small percentage of the officers sufficiently skilled and talented to fight in today’s strategic environment.

3. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Mihara, Army Strategist, U.S. Army North (Fifth Army)

GRADE: C

Developing strategic leaders properly necessarily centers on proven competence rather than presumptions of competence through scheduled, predetermined milestones. Strategy deals with complex future phenomena (i.e., fundamentally unknowable) rather than immediate, tangible circumstances which are subject to resolution through prescribed tactics, techniques, and procedures. This requirement is distinct from those that pertain to tactical leaders.

Strategic competence is not amenable to development through programmed gateways, such as those embraced by OPMS XXI, fostered by DOPMA, or through on-the-job training. Mastery of strategic expert knowledge is largely dependent on individuals’ talents, temperament, and motivation. Those characteristics are relevant to the performance of tactical leaders, particularly when operating under duress, but they are not essential to the technical competence of such leaders.

In preparing for a complex and dynamic future, strategic leaders rely upon their talents, temperament, and motivation more than theoretical and empirical knowledge. Strategic leaders rely upon a deep understanding of the competitive environment as it is will be – skills that are seldom the product of the promotion and assignments system.

The degree to which Functional Area 59 (Army Strategist) officers are perceived to be uniquely useful in formulating military strategy indicates the severity of Army system’s shortcomings for cultivating strategic leadership. In many ways, this is an implicit confession that the system does not reliably produce strategically competent leaders. Shouldn’t all senior military officers be strategists?

we expect strategic excellence to guide us in new directions with unconventional solutions

4. Dr. Tom Nagle, U.S. Army Retired; Former Army Strategist

GRADE: ?

A better question might be, “If the US Army did develop highly skilled strategic leaders, would the Army realize it?”

Almost by definition, we expect strategic excellence to guide us in new directions with unconventional solutions – otherwise, why deviate from the status quo in search of the missing strategic skills?

The development and employment of the force in the modern age requires a complex web of overlapping decision and execution systems. The issue is whether or not these systems would allow strategic leaders to exert the type of influence that would be necessary to recognize strategic excellence in the first place.

The Army’s (and DoD’s) structure and decision systems are still based on industrial-age organization – best suited to provide pre-determined outputs. Yet we live in an information-age era, where being able to embrace emergent strategy is the key to success.

To be effective in today’s complex environment, leaders must be able to conduct “strategic experiments” to find useful points of leverage, rapidly shift organizations to exploit unexpected success, and divest of under-performing efforts to free up resources. All of these actions are hindered by systems and structures built for a different era.

Today’s innovative companies actually expend a great deal of effort on their organization and decision systems to ensure they can act upon their strategic insights – an internally-directed process of (often painful) creative destruction. When DoD or the Army undertakes innovation efforts, they tend to mistakenly focus on the artifacts of the organizational culture of these companies, while missing the more profound points.

5. Lieutenant Colonel Chad Storlie, U.S. Army Retired, former Special Forces officer

Grade: C- (B+ in Execution, D- in Results)

The US Army Strategic Leaders – Excellence In Execution, Irrelevance In Results

U.S. Army strategic leaders must be “War Winners,” not “War Managers.” Yes, US Army strategic leaders (O6 and above) have displayed remarkable consistency in managing conflict over the last 18 years (FY 2000 forward). First, the US Army determined how to resource and fight two wars in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan plus maintain troop presence in Europe, Asia, and Africa. US Army leaders created tactics, equipment, training, and leader development that reduced casualties, created consistent tactical victories, and allowed the US Army to continue to fight and deploy across 18 years in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria. The US Army also maintained an immense logistical and innovation focus to improve medical care, develop better personal equipment for soldiers, and succeed in a range of missions from war fighting to logistics to training foreign forces. In this way, the US Army Strategic leaders get a B+ grade for delivering excellent execution results.

Now the bad news. Management is not warfighting and warfighting alone is not winning. While the US Army was able to maintain troops in the field, US Army strategic leaders were never able to translate their “management” skills into relevant, sustainable, and enduring battlefield results. When we look across Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan today after 18 years of near continuous US Army operations in the region, there is no metric, criteria, or standard that states the US Army meet the desired strategic outcomes in the region. The US Army is no better at training foreign military forces; working towards consistent outcomes in complex social, economic, and tribal landscapes; working in extreme foreign cultures; or adopting a counter veiling warfighting doctrine, counter-insurgency, into a long term, results driven strategic approach that was believed by Army leaders.

The US Army needs to place Field Grade officers into Master’s programs in Business, Government, or Language and then post them for two years inside foreign militaries, at small businesses (not Fortune 1000), and inside US trade delegations to work on taking resources and translating those resources into results – every day. Small business fights for its existence and must win every day. In business, if you don’t win every day, your competitors make you irrelevant.

The US Army needs to refocus on conflict termination, conflict resolution, and enduring measurement of metrics that point to reaching conflict termination. War is to be fought and won, not fought and managed.

6. Dr. Jan Kallberg, Army Cyber Institute at West Point

GRADE: Pass

I find the grade “P” for a pass suitable. A pass is earned for coursework that is a part of an undertaking, an effort that has not yet revealed its output, as preparations for a dissertation. The future war is likely a peer-conflict were our adversaries acts fast to maximize their advantage. The initial confrontation could be a quick, brutal, and the defending US force inferior at the initial stages of the regional conflict. It doesn’t mean the war is lost; it is just that you and your soldiers happen to be in the worst spot at the moment.

During the 80s to the end of the Cold War, I was a Swedish reserve officer. As such, preparing for being outnumbered by a swift Soviet onslaught in the Arctics, and in a situation of strategic inferiority seeking tactical superiority leveraged by terrain and climate. I found in this role of preparing for your unit’s graceful defeat it is impossible to do it well without understanding and accepting why.

Sixty-five years after the Korean War, I think we today underestimate what a high casualty peer-conflict means. The wording managers of violence lose meaning when you are the target of the violence. Therefore, I am a believer that strategic leaders need to be open-minded, have integrity, and be leaders of character. A strategic leader needs to understand why this matters, why we are doing this, why we are taking these risks, and convey this understanding.

In my view, American strategic leaders are more adaptive and capable than we in our self-criticism might assess. They benefit from a broad mix of academic studies, a deep understanding of the society that sends them out, and a strong foundation in strategic craftmanship. The graded event hasn’t occurred yet, and the passing grade is earned, with a hopeful outlook.

The views expressed in this Whiteboard Exercise are those of the contributors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, U.S. Army, or Department of Defense.

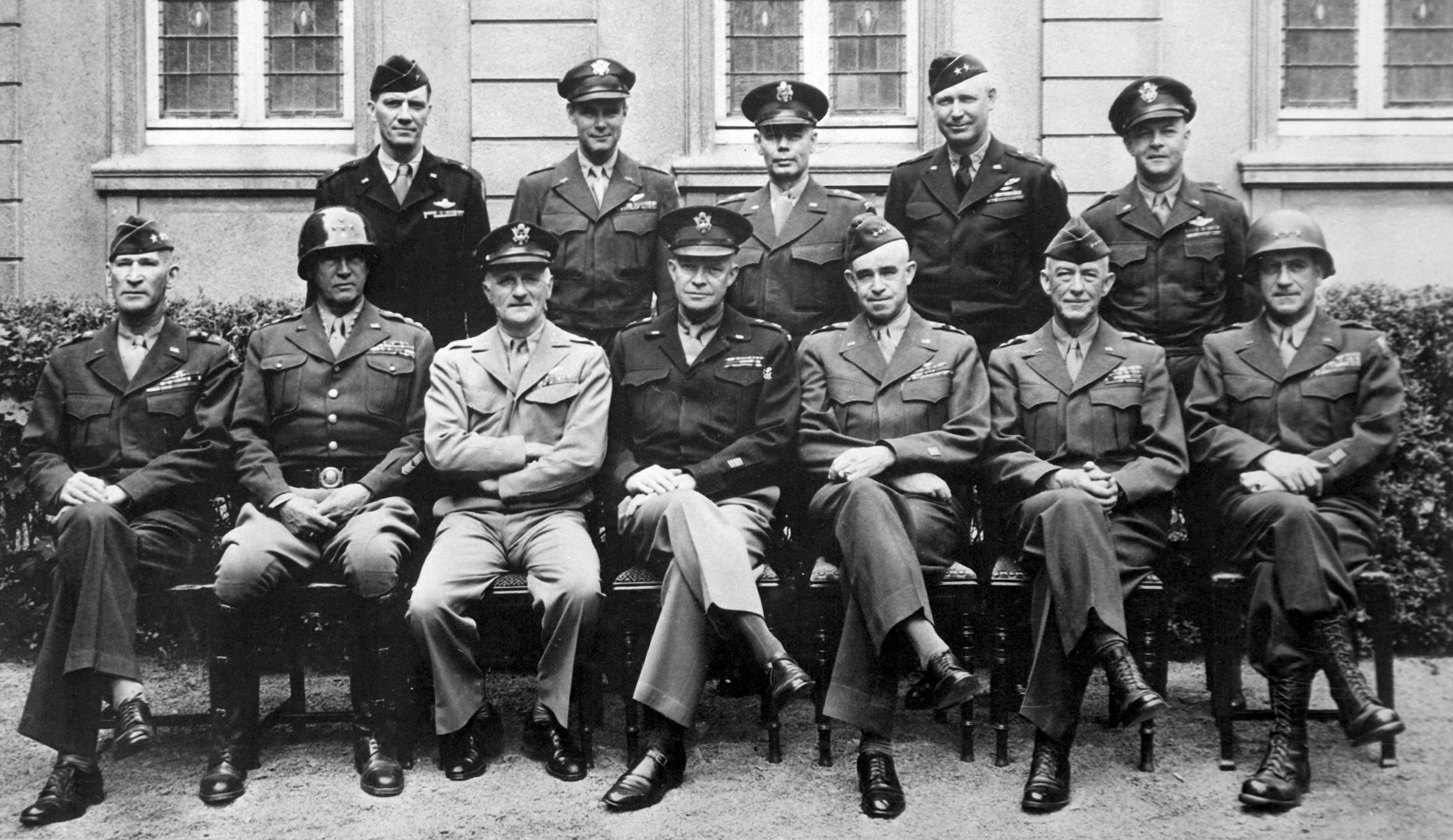

Photo: Senior American commanders of the European theater of World War II. Seated are (from left to right) Gens. William H. Simpson, George S. Patton, Carl A. Spaatz, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Omar Bradley, Courtney H. Hodges, and Leonard T. Gerow; standing are (from left to right) Gens. Ralph F. Stearley, Hoyt Vandenberg, Walter Bedell Smith, Otto P. Weyland, and Richard E. Nugent.

Photo Credit: U.S. Army Photo, public domain

Other Releases in the Whiteboard series:

- THE ADMINISTRATION’S TOP FOREIGN POLICY PRIORITY (A WHITEBOARD)

- AFTER 2020, WHAT’S NEXT? (A WHITEBOARD)

- IMAGINING OVERMATCH: CRITICAL DOMAINS IN THE NEXT WAR (A WHITEBOARD)

- THAT ONE MOST IMPORTANT THING: (A WHITEBOARD)

- SHALL WE PLAY A GAME?

(WARGAMING ROOM) - WAR(GAMING) WHAT IS IT GOOD FOR? (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION REVISITED: (A WHITEBOARD)

- WHAT GOOD IS GRAND STRATEGY? (A WHITEBOARD)

- THE UNITED NATIONS’ GREATEST ACCOMPLISHMENT: (A WHITEBOARD)

- LEADERSHIP ROLE MODELS IN FICTION: (A WHITEBOARD)