“Let your military measures be strong enough to repel the invader and keep the peace, and not so strong as to unnecessarily harass and persecute the people.”

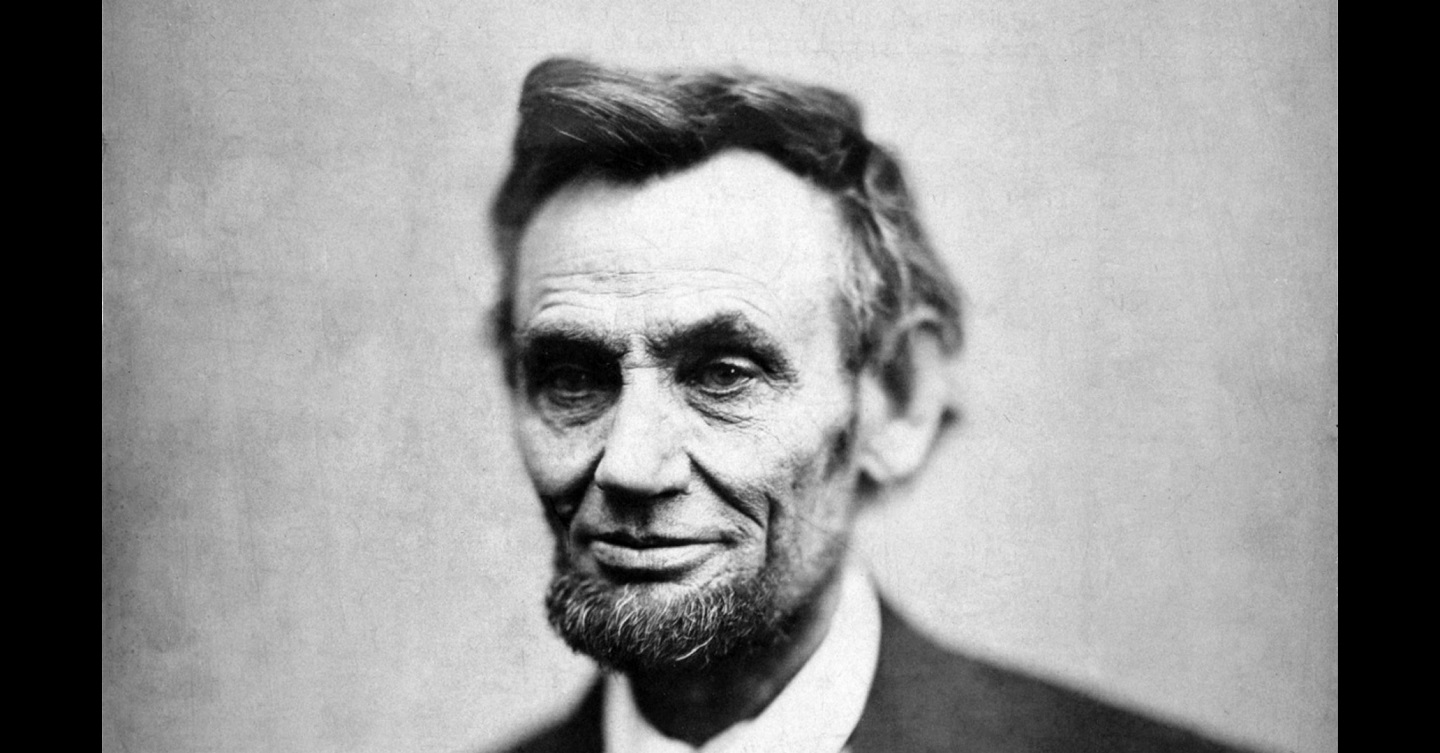

President Abraham Lincoln, In a letter to Union General John. M. Schofield, May 27, 1863

Every one of President Abraham Lincoln’s strategic undertakings as President was designed to preserve the Union. In addition to military action, he strove to inform, persuade, provide economic incentives, and communicate both hope and resolve. His deliberate words and symbolic actions were put into play from the beginning of the conflict in 1861, through the duration of the war, and to the Confederacy’s surrender in 1865. While students of the American Civil War tend to focus on strategic and operational analysis of major land battles and commander’s decision-making, the exercise of diplomacy, the use of strategic information, and economic initiatives likewise had an effect on not only achieving emancipation and preserving the Union, but also in creating the potential for many of America’s national achievements of the 20th century and beyond. There is considerable literature analyzing Lincoln’s mastery of national strategy and grand design, all of which contribute to his reputation as President and Commander-in-Chief. In fact, in June 2021, C-Span’s Historian Survey on Presidential Leadership ranked Lincoln #1 among U.S. Presidents for the fourth consecutive year.

Even as the first battles of the war were occurring, Lincoln looked for effective options apart from military engagement. He first tried a financial enticement, hoping to persuade citizens to reject the Confederate stance through a compelling draw, improving their children’s access to education. In 1862, Congress passed the Land Grant College Act, sponsored by Vermont senator Justin Smith Morrill. It provided grants to states to establish colleges of “agriculture and mechanical arts,” but that provision pointedly did not apply to those states siding with the Confederacy. Only by renouncing slavery and rejoining the Union could rebel states partake of this federal act of economic development.

Under provision six of the Act, “No State while in a condition of rebellion or insurrection against the government of the United States shall be entitled to the benefit of this act.” If this act, a hand outstretched to pull states back into the Union or prevent them from leaving, was indeed a gesture made in conciliation, it was not effective. Not one rebel state took him up on the offer.

Lincoln went on to try other means of both persuasion and pressure, displaying his determination to hold the Union together, while simultaneously increasing the efforts of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) to force the Confederacy to surrender. In one emblematic decision, he insisted that construction on the ‘people’s house’ proceed throughout the war years. Work on the white marble dome of the U.S. Capitol continued. Lincoln thought the symbolism of that effort important. “If people see the Capitol going on, it is a sign we intend the Union to go on.” It was strategic communication displayed through both words and in action.

On September 22, 1862, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation. It took effect in January 1863, freeing those persons held in slavery in rebel states: stating they “Shall be then and henceforward forever free.”

Concurrently, the President commissioned Francis Lieber, a professor at Columbia University to develop a code providing policies for the four major areas of warfare: martial law, military jurisdiction, punishment of spies/deserters, and the treatment of prisoners of war. It took Lieber a year to finish the task, but Lincoln was pleased with the effort, noting it would maintain good order and discipline in the ranks, and promote a sense of decency among the troops.

The completed Lieber Code arrived in the middle of war as a directive from the Commander-in-Chief to his soldiers. This first formal codification of the laws of warfare was formally titled, “Instructions for the Government of Armies of The United States in the field, General Order No. 100.” The Order was issued on April 24, 1863. In a historic signing ceremony, Lincoln gathered members of his cabinet and the Army, including Brigadier General Joseph Holt, the Judge Advocate General of the Army. He was the first Judge Advocate General promoted to the rank of Brigadier General.

With its inseparable link to the legitimacy of a conflict, The Code held particular significance for the treatment of Black troops. The Lieber Code specifically stated that the law of war did not permit racial discrimination. By 1863 the Union Army was deploying units of African American soldiers. Confederate commanders refused to recognize their legitimacy, treating captured African American soldiers as escaped slaves, rather than as prisoners of war. The Lieber code asserted “the law of nations knows of no distinction of color (Article 58).” The literature on the vast impacts of the Lieber Code, both in the U.S. and internationally continues to expand. Legal experts recognize the impacts and have continued to ensure the lessons from the Lieber Code remain before new generations practicing military law. In 2011 the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General (JAG) Corps commissioned a print by military artist Mort Kunstler depicting Lincoln signing the Lieber Code into law.

At the time of the Lieber Code signing, and after two devastating years of war, the tide was beginning to shift on the battlefield. There were two major turning points that July. General Meade defeated Robert E. Lee’s troops at Gettysburg in three harsh days of fighting and on the 4th, Grant’s Army defeated the Confederates at Vicksburg, concluding the Vicksburg Campaign. Lincoln recognized the significance of Grant’s victory, calling Vicksburg, “The key to the war.”

Concurrently, the President recognized that ordinary citizens in the Union had been losing faith in the ultimate outcome of the war. In 1862, during the dark, somber days when General Lee’s Army held the upper hand, seventeen Union states declared state holidays for thanksgiving and prayer. By the summer of 1863, Lincoln got ahead of the trend, and declared a national day of thanksgiving. While a day of thanksgiving had first been initiated under President Washington, national recognition of the event had faded from memory. Lincoln knew it was time to resurrect it.

That first National Day of Thanksgiving was held on August 6th, 1863. Across the country, it was celebrated in churches and communities as a day of hope and prayer. Despite the staggering loss of life and the long war’s effects on the economy, people began to look to the future. In October he announced the last Thursday in November would be recognized as another national day of Thanksgiving. It was a day meant to celebrate the survival of the Union and the reconciliation of all her people, through giving thanks for the victory at Gettysburg. A week earlier, in his address at Gettysburg, Lincoln made the same point – that the nation would have a ‘new birth of freedom’ following the war. In 1864, Thanksgiving became a permanent fixture on the national calendar.

Throughout his time in office, Lincoln had been employing all elements of national power at his disposal to persuade border slave states to adopt gradual emancipation policies – through compensating them for financial losses and making it attractive for these states to both abolish slavery and remain in the Union. Even after issuing the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, he continued his state by state campaign to shift the balance of power. In the last year of the war, six states, Maryland and Missouri (which had never seceded,) and Virginia, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Tennessee, abolished slavery. Most abolished slavery when forced, upon losing militarily to the North. In Texas, slaves were freed with the late arrival of news of the Proclamation, delivered by arriving Union troops on June 19, 1865. Juneteenth, now a federal holiday, is a testament to the power of the Proclamation. Adding these states to the growing list of already free states made ratification of the 13th Amendment possible in December 1865 – eight months following Lincoln’s death.

Although it had been officially abolished, the institution of slavery lingered on following the war. Today, the prevailing view of Reconstruction is one of failure to achieve lasting results in equality for the freed slave population – that of ensuring African Americans were treated equally under the law, were not disenfranchised from access to their rights as citizens and were not subject to restrictions that prevented them from accessing the vote.

Many of Lincoln’s other non-military wartime efforts did have long-term positive effects. By the time of his second inaugural address, he was already laying the groundwork for additional efforts to encourage reconciliation with the south. Had he not been assassinated just months into his second term as President, perhaps a number of his strategies, may well have been even more influential and long lasting.

The Land Grant College Act quickly began to bear fruit. Just 50 years after the end of the war, the U.S. was graduating 3,000 engineers a year, making this country the global leader in producing engineers. Lincoln’s investment in the educational future of America was beginning to have a significant impact on the economic development of the nation. With southern states back in the Union, it was important that they be able to share in the new opportunity for accessible education.

In 1890, there was a second iteration of the Morrill Act, aimed directly at the former Confederate states. But to qualify, those states had to attest that race was not a criterion for admission to the new colleges. Once they agreed, over 70 colleges and universities were established, based on the gifts from both Morrill acts, including several Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). The act required the land Grant colleges to conduct training in military tactics, a provision that resulted in the establishment of what would later become the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC). Norwich University was the first to promote the idea of the ‘citizen soldier.’

Thanksgiving continued as a uniquely American day of thanks and hope. In 1939, under President Roosevelt, Thanksgiving became a federal holiday.

The Lieber Code’s reputation grew, rapidly achieving global influence. It later became the basis for all international treaties and the customs of land warfare, including the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and the Geneva Accords of 1954, which addressed the separation of Vietnam. These first codifications of the Laws of War formed the basis for most regulations for the ethical conduct of warfare in the world and laid the groundwork for evolving human rights laws.

President Lincoln excelled as a wartime President. His efforts to engage every element of national power at his disposal had a clear and decisive effect on the war’s outcome, from the battlefield to the state house, to communities, businesses and universities affected by his decisions – on how, when, and where to fight, to create economic incentives, and to persuade. But Lincoln’s achievements went beyond the operational – to end the war and preserve the Union. As a strategic leader, he exercised the vision that had an enduring effect: building America’s future.

The summation of Abraham Lincoln’s exercise of every Presidential tool at his disposal can be best summarized and represented by the presence of the U.S. Capitol itself. Inside the dome the words of the national motto remind us of this achievement:

“E Pluribus Unum – Out of Many, One.”

Mari Eder is a Featured Contributor to WAR ROOM. She is a retired major general in the U.S. Army and an expert in public relations and strategic communication. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the U.S. Department of the Interior

WAR ROOM Releases by Mari Eder:

- IN PLAIN SIGHT – THE INSECURE LEADER – A BULLY OF A BOSS

- AFTER THE INFO-APOCALYPSE (AA) (PART 1) – TECH THE UNTAMED

- THE INFORMATION APOCALYPSE PART IX: ART VERSUS SCIENCE

- THE INFORMATION APOCALYPSE PART VIII: CIVICS LESSONS

- THE INFORMATION APOCALYPSE, PART VI: PARANOIA AND PRIVACY

- THE INFORMATION APOCALYPSE, PART V: THE FOURTH ESTATE

- THE INFORMATION APOCALYPSE, PART IV: INTELLIGENCE SECRETS OF SUCCESS

- THE INFORMATION APOCALYPSE, PART III: THE WAR ON REALITY

- INFORMATION APOCALYPSE, PART II: THIS TIME, IT’S PERSONAL

- THE INFORMATION APOCALYPSE … IS ALREADY HERE

You would think Army War college could dig through the Reconstruction Smoke & Mirrors and include “Corwin Agreement” and Lincoln’s $200 enlistment bonus to European conscripted mercenaries.

Thanks, General Eder, for this excellent article. Like van Clausewitz said, “War is a continuation of policy with other means.” I never put the Land Grant Colleges in that prism. I also never heard of the Leiber Code and its significance, to this very day, in the application of moral philosophy in the context of the conduct of war. Keep up the good work. MTG

Thank you Sir, an excellent piece on a dynamic, thoughtful man who, through intense depression, united this nation. Few in history have been called to such acts, that pivotal period could not have been more in need of a man with such character, foresight, and strength.

George Colby