AT ALL TIMES…LEADERS MUST ENDEAVOR TO DEMONSTRATE UNIMPEACHABLE INTEGRITY AND CHARACTER.

We can—and should—expect leaders to make honest mistakes in the face of complex challenges, hardships, dilemmas, and difficult decisions. At all times, however, leaders must endeavor to demonstrate unimpeachable integrity and character. Leaders must be the moral and ethical compass for those they lead in order to instill trust. Why? Because in times of hardship and in the face of complex challenges, trust is the bedrock of successful leadership.

In 2012, the chief of staff of the Army approved the doctrinal publication, Army Leadership. In the foreword, Gen. Raymond Odierno wrote that being a leader is not about power, giving orders, and cultivating image. Being a leader is about earning respect, leading by example, and inspiring others.

In the course of a three-year U.S. Army doctorate program, this author conducted over 100 interviews with senior national security experts serving across six presidential administrations from President Ronald Reagan to President Donald Trump. Among them were two former Secretaries of State, five National Security Advisors, three Deputy National Security Advisors, four CIA Directors, two Chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, two Vice Chairmen of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, three Chiefs of Staff of the Army, two Vice Chiefs of Staff of the Army, one Commandant of the U.S. Marine Corps, twelve 4-star Combatant Commanders, eight Ambassadors, multiple 1-star, 2-star, and 3-star generals and admirals, and multiple policy experts from thirteen universities and six major think tanks.

In the course of this research, the author found that strategic military leaders constitute a powerful epistemic community steeped in knowledge and experience. As such, they exhibit key conceptual attributes that, taken together, make them exceptionally influential in the domain of national security and foreign policy. Some of these attributes include having a shared profession and ethos; strong organizational culture; possessing recognized expertise and knowledge; and demonstrating strong internal cohesion and intra-group trust.

Military professionals, even when they may vehemently disagree with one another, still exhibit these communal attributes because they ultimately trust one another. They expect members of their profession to uphold the Army Values, to be honest, to tell the truth. These attributes are what make the Army, and the United States military as a whole, so trusted by American society. The prestige of the military rests on our credibility.

Understanding this dynamic is incredibly important in the context of modern war and a complex strategic environment. Rapidly advancing development of robotics, augmented reality, unmanned weapon systems, hypersonic technologies, space- and cyber-based capabilities, artificial intelligence, and cloud-enabled informatics drive policy process, decision-making, and mission command at an ever-increasing pace. In reaction, elected officials increasingly look to the military and its senior leadership to take on the United States’ most complex, strategic problems.

In 2018, the RAND Corporation published an interesting book, Truth Decay: An Initial Exploration of the Diminishing Role of Facts and Analysis in American Public Life. The book explores an increasing “disregard for facts, data, and analysis” in our daily political and civil discourse in the United States. Opinions, anecdotes, and experiential narratives often replace the objective truth. But who are the agents of truth decay?

Historically, the media has been blamed for blurring the line between opinion and fact, political bias and public good. As far back as the 1830s, Alexis de Tocqueville observed immense inadequacies in America’s free press. He noted that the media suffered from a lack objectivity and incalculable bias, and criticized it for being driven by profit. Tocqueville explained that we should expect the media to be both trivial and virulent in times of uncertainty and political tension. Regardless, he championed a free press as essential to the protection of American liberties and our democracy.

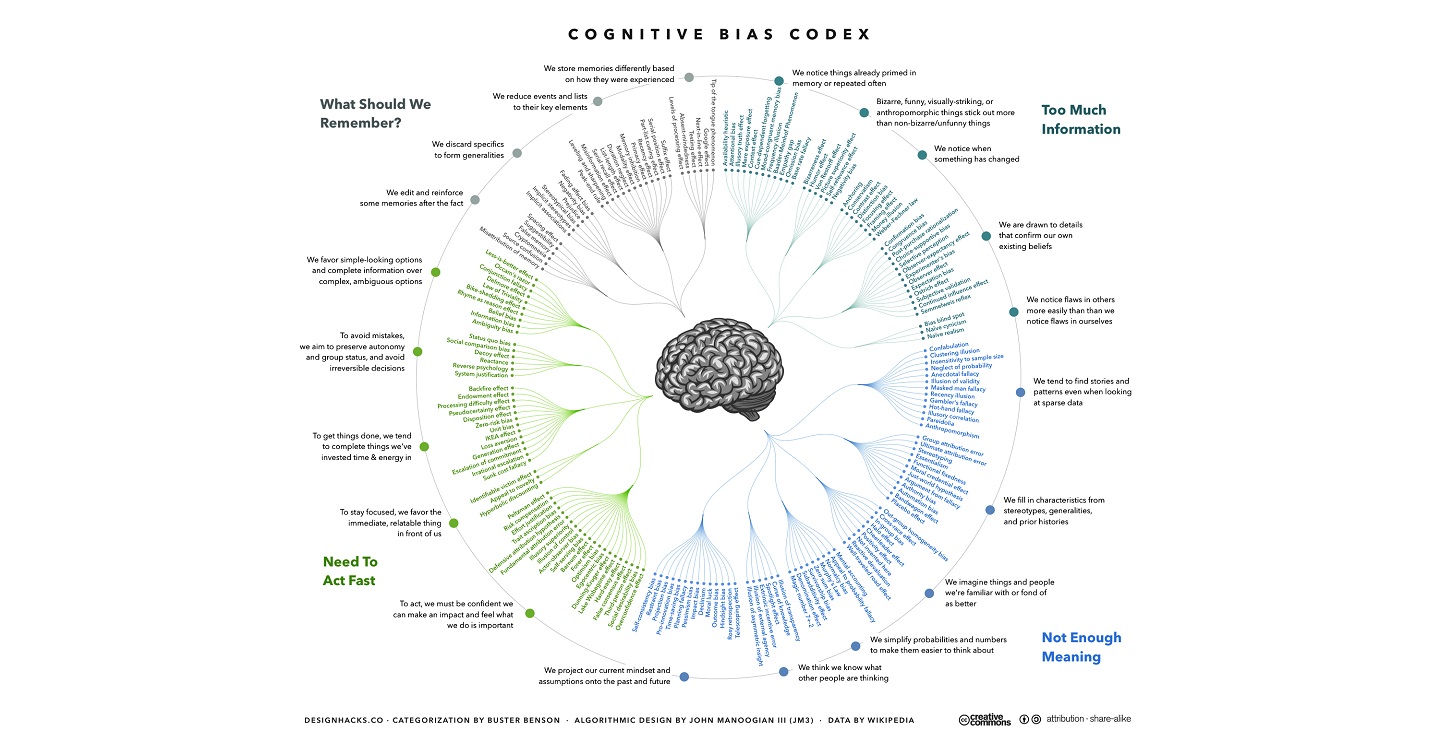

Sadly, the biggest agent of truth decay is the individual–you, me, us, collectively. Our cognitive biases. Our preexisting beliefs. Our reliance on mental shortcuts..

More recently, RAND finds that elected officials have been identified as agents of truth decay. Falsehoods, lies, immoral and unethical behavior, abuse of office and authority, unkept promises, and excessive partisan bickering all contribute to the erosion of trust Americans have in their governmental institutions. In a survey of Gallup Polls, interesting trends related to the media and elected officials surface. For well over a decade, public approval of Congress, the presidency, the media, both political parties, and the government as a whole consistently falls below 50 percent. A majority of Americans consistently believe that our elected leaders will not do what is right and the media is tremendously biased. Both are, in the minds of most Americans, crooked and dishonest.

Sadly, the biggest agent of truth decay is the individual–you, me, us, collectively. Our cognitive biases. Our preexisting beliefs. Our reliance on mental shortcuts. These variables, taken together, have increased the influence that others have on us through social media and twenty-four-hour news cycles. We no longer take the time to discriminate between opinion, fact, and falsehood. We accept experiential narrative as truth. Finally, we allow our political differences and disagreements to cause in us an ever-greater contempt.

The world has repeatedly faced complex, even existential, challenges. As members of the Army profession, tasked to fight lead, fight, and win in today’s complex, strategic environment, we will inevitably make mistakes. We will face fear and irrational thoughts. Likewise, we will witness great courage and leadership. To this end, we must hold ourselves and our profession to a high standard. We must expect moral leadership, both within our profession and across our governmental institutions.

Likewise, empathy is one of the most important characteristics of both leaders and subordinates. Criticism and emotionally driven disparagement of those in leadership is unproductive. Senior military and civilian officials, under the burden of leadership, have unique access to information and perspective that subordinates do not have. It is incumbent on us hold leaders accountable, but also to view them with respect, demonstrating support, and expressing empathy.

As the United States and the world face the challenge of a global pandemic and we begin to see the incredible challenges the military may be called to confront, moral leadership matters. We must be able to trust both our elected officials and the news media to tell us the truth. Most importantly, however, we have an individual responsibility.

As Army leaders, we must be hyper-vigilant in protecting our profession. We must protect against partisanship in our ranks; against politicization of our profession; against contempt for those with whom we may disagree; and against a lack of intellectual curiosity to find and understand truth. Failure to hold ourselves and our leaders accountable risks squandering the public trust American society has in its Army and military. Finding our profession compromised, all the strategic knowledge and experience that our military and national leaders have cultivated will be for naught.

Todd A. Schmidt, Ph.D., is a Colonel in the U.S. Army and the Director (J5), Plans, Policy, & Allied Integration, Joint Functional Component Command – Integrated Missile Defense (JFCC-IMD). He is a U.S. Army Goodpaster Scholar and SAMS alumni. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Photo Description: Wikipedia’s complete (as of 2016) list of cognitive biases

Photo Credit: Arranged and designed by John Manoogian III (jm3). Categories and descriptions originally by Buster Benson. Used under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.