Murray…highlights the German military’s failure as a whole to understand how the Industrial Revolution had transformed warfighting.

Written histories, it is said, speak to each generation differently, enabling readers to interpret them within the framework of their own experiences. As such, a rereading of Williamson Murray’s Luftwaffe—first published in 1985—is especially timely. Although offering more of an implicit argument than an outright thesis, the book consistently depicts the Luftwaffe’s defeat as practically a foregone conclusion. The writing was on the proverbial wall as early as the inter-war period. Such an argument could be viewed as teleological. Murray’s work, though, allows for plenty of opportunities for the Luftwaffe to have corrected its mistakes.

And it is those mistakes that are worth revisiting today. Most importantly, the Luftwaffe and the German military as a whole had limited strategic and logistic abilities, to put it rather kindly. Whether or not the past decades of U.S. history place the U.S. military in the same category is a subject for debate. A recent report on sealift, for example, is troublesome. Moreover, in preparing for future wars, it currently demonstrates a predilection for operational over strategic solutions, as epitomized by multi-domain operations, which focuses on the “ways” in which the U.S. military must connect its various branches of warfighters. “Ends,” it is assumed, must wait until an actual conflict unfolds. Others insist, however, that strategy is just as germane to peacetime as it is to wartime. In Luftwaffe, Murray also points out the dangers of an officer corps of “technocrats and operational experts with limited vision.”

Murray similarly highlights the German military’s failure as a whole to understand how the Industrial Revolution had transformed warfighting. Today the U.S. military stands at potentially a similar precipice, as it wrestles with what some have described as a shift from the industrial to the information age. If data should be a strategic asset, is it of greater strategic importance than industrial output? The U.S. military seems to suggest the answer is yes, although this answer is worth wrestling with deeply.

As Murray makes clear, Germany never managed to get its warfighting production in order, in part because of significant planning failures. Many officers, for example, envisioned building a fleet of strategic bombers, but Germany had neither the engineers, the “industrial capacity,” or the ability to do so. Similarly, it is unclear how well the U.S. military has positioned itself in regard to industry to fight a peer-on-peer conflict, especially given its embrace of the “exquisite few.” He also notes how early German victories convinced the Luftwaffe that its production plans were sound when, in reality, they were anything but wise. Even before the United States joined the air war in the European theater, the Luftwaffe had “lost nearly its entire complement of aircraft” two years in a row. By the time the United States Air Force achieved the ability to launch significant numbers of sorties against Germany proper, the Luftwaffe had been attritted heavily for four years, most painfully in 1943 by the British.

While the U.S. has maintained enough mass to be able to experiment with multiple strategies over the last several decades, there is no guarantee that such would be the case in future peer-on-peer conflicts. Again, here Murray points to the German tendency, particularly in the Battle of Britain, to try multiple strategies simultaneously, thus limiting any from being “decisive.”

The irony of airpower as a way to avoid the attrition warfare of World War I also runs throughout the book as a dominant theme. Murray even suggests that we look too much for war-changing victories, such as the Battle of Britain, at the expense of appreciating incremental attrition over time. Murray also highlights how systemic weaknesses already had begun to undermine the Luftwaffe even prior to engaging in an air war over British skies.

As each generation prepares for future conflict, it is critical to consider not only change but continuity.

Rereading Murray’s work (or downloading it for free from Air University Press) returns readers to a critical peer conflict of the twentieth century, forcing us to wrestle with whether attrition really has been consigned to dusty library shelves. Today’s U.S. Air Force, for example, suggests that attrition is “old-fashioned.”

It also bears considering the extent to which information warfare may or may not be supplanting traditional kinetic effects. As each generation prepares for future conflict, it is critical to consider not only change but continuity. It can be tempting to get overly caught up in the change and forget how much continues to endure in warfare. The Luftwaffe’s story is thankfully one of failure for the Nazi regime. But that story, told so well by Williamson Murray in this timeless book, can still teach us something as we prepare for better future endings for our conflicts and wars.

Note: The cited portion of the book used to provide specific hyperlinks can be viewed here. The free version can be downloaded here.

Heather Venable is an associate professor of military and security studies at the U.S. Air Command and Staff College and teaches in the Department of Airpower. She also is the author of How the Few Became the Proud: Crafting the Marine Corps Mystique, 1874-1918. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, the U.S. Air Force or the Department of Defense.

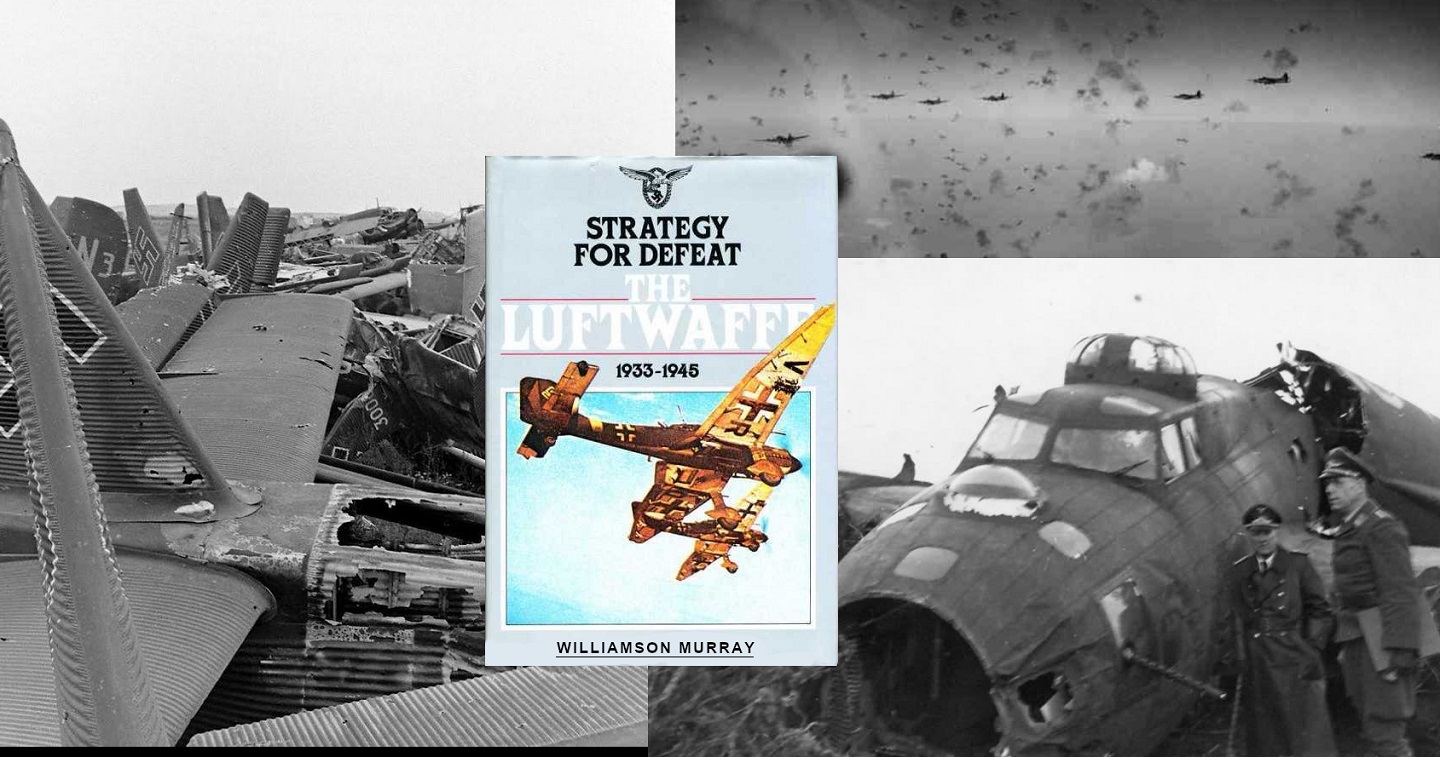

Photo Description: (LEFT) Results of an Army Air Force fighter sweep on a Luftwaffe air field. Starting with ‘Big Week,’ American fighters, after escorting bombers to their targets in Germany, would strafe Luftwaffe airfields to catch the German fighters on the ground or on takeoff or landing. (TOP RIGHT) B-17 formation under attack during a bombing raid on an industrial target in Germany, probably sometime in 1943. (BOTTOM RIGHT) Several Luftwaffe officers inspect a crashed B-17 somewhere in Germany. Between August 1942 and May 8, 1945, Eighth Air Force flew 10,631 missions and lost 4,145 B-17s, each with a 10-man crew.

Photo Credit: U.S.A.A.F Photos circa 1942-45

Other releases in the “Dusty Shelves” series:

- THE ARMED FORCES OFFICER (1988): THE FORGOTTEN PRIMER ON LEADERSHIP

(DUSTY SHELVES) - RIDGWAY’S KOREAN WAR

(DUSTY SHELVES) - ALL WAR IS LOCAL: ANTHONY QUAYLE’S EIGHT HOURS FROM ENGLAND

- POST-WAR TRUTH TELLING: THE WAR MANAGERS

- DYE: EXALTING THE TAIL OF THE AIRPOWER TOOTH

(DUSTY SHELVES) - PEACE FORMS: LOOKING BACK TO THE FUTURE OF WAR AND ANTI-WAR

- SHERMAN: THE OUTLIER OF INTERWAR “ATLANTIC” AIR THEORY?

(DUSTY SHELVES) - STRUGGLING TO SEE THE FUTURE: UNLESS PEACE COMES

(DUSTY SHELVES) - “ALL INVADED PEOPLE WANT TO RESIST”: STEINBECK’S THE MOON IS DOWN

(DUSTY SHELVES) - RACE TO THE SWIFT: APPLICATIONS IN 21st CENTURY WARFARE

(DUSTY SHELVES)